Marjorie Sweeting | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 February 1920 Fulham, London |

| Died | 31 December 1994 Oxford, England |

| Resting place | Enstone, Oxfordshire |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geomorphologist |

Marjorie Mary Sweeting (28 February 1920 – 31 December 1994 in Oxford), was a British geomorphologist specializing in karst phenomena. Sweeting had gained extensive knowledge on various topographies and landscapes by travelling around the world to places such as Greece, Australia, Czechoslovakia, United States, Canada, South Africa, Belize, and most notably China. She published Karst Landforms (Macmillan 1972), and Karst in China: its Geomorphology and Environment (Springer 1995). The latter is the first comprehensive Western account of China's karst,[1][2] and one of the first western published works on the karst found within China, despite being a male dominated field.[3]

Personal life and education

Marjorie May Sweeting was born to George Scotland Sweeting and his wife Ellen Louisa Liddiard in Fulham in 1920. She had no siblings. In her childhood her father G.S. Sweeting was a geology lecturer at the Imperial College in London.[4]

Her secondary education took place in Mayfield School and she later graduated in 1941 from Newnham College, Cambridge. She was accepted as a Caroline Turtle Research Fellow at Newnham College, Cambridge during 1942 for a year, which later she returned in 1945 for the Marion Kennedy Research.[5] She received her doctorate for her thesis "The Landforms on Carboniferous Limestone of the Ingleborough District in N.W. Yorkshire" in 1948.[6]

Alongside her passion for fieldwork, conferencing and teaching, Sweeting enjoyed travelling, the opera, and watching entertainment such as sports.[4] Sweeting rowed in the Cambridge Women’s Blue Boat as she was an active member of the community and enjoyed partaking in such events.[7]

Marjorie Sweeting died in 1994 at the age of 74 after succumbing to cancer, her body was interred at Enstone Village. Marjorie had no living relatives, for this reason her estate contributed funds to St. Hughs College, Newnham College, Oxford, The Royal Geographic Society and Cambridge.[8]

Career

In 1987, Marjorie Sweeting retired from her position as a reader in Geography at The University of Oxford. She was also a Tutor at St Hugh's College 1951–1987 (Emeritus), aswell as a lecturer and reader at Oxford University 1954–1987. During 1948, Sweeting became a PhD candidate and wrote her thesis based on The Landforms of the Carboniferous Limestone of Ingleborough District, N.W. Yorkshire.[5] In 1951, Marjorie Sweeting was appointed as a lecturer and director of studies in Geography at St. Hugh's College, and in 1983 she was named the acting head of the school.[9] Marjorie Sweeting was the first western-geologist to study karsts. The study, research, and analysis she released as a result of this became incredibly popular as her concepts are still expanded and studied by new-coming geologists.[10]

Sweeting served on the Karst Commission of the International Geographical Union, where she came to work on a new project titled Man's Impact on the Karst. Additionally, Sweeting worked with Gordon Warwick in support of the International Speleological Union where she was in charge of the Karst Denudation. Another one of Marjorie's accomplishments in her career was being a leader on an expedition called the “Expedition to Gunung Mulu” from 1977 to 1978. She was the program director for the Landform and Hydrology Survey for the Royal Geographical Society.[11] The expedition was held to observe speeds of erosion and how quickly land was being formed in a forest of equatorial conditions.[12] Much of Sweeting's early work was focused on the shape of karst landforms, the geological control, and landscape denudation rates. In addition, using her previous interest in rates, she helped establish the importance of mineralogy when controlling weather rates, assisting in field studies and analysis in Jamaica and Puerto Rico.[4] Her book, Karst Landforms (Macmillan 1972), contained the synthesis of her extensive travels, her and her research students' work, and her collaborations and discussions with the major researchers in the field of limestone studies. The book is considered a benchmark of its time in karst studies and is especially influential as China opened up as a region for research after its publication.[4] many people in Britain did not believe in the extravagance of paintings and photographs of the limestone karsts in China prior to Sweeting’s “Expedition to Gunung Mulu” (Sweeting, 1978)[13]

Marjorie Sweeting has been a prominent British geomorphologist and professor as she has an excellent understanding of geomorphology. She was constantly discussing new concepts and ideas that later went on to improve geological understandings of limestone landscapes.[14] An integral aspect of geology is thorough and focused analysis of the tangible world. It is the deliberate observation of the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic layers in Earth’s crust that reveal the history of the planet, which can then be correlated to construct an adequate story. Marjorie Sweeting professionalised in exactly this as her passion attracted and drew her to topographic and geophysical research. She released geological literature on certain areas that had not been analysed in depth or used as earth science, for example, the karst areas of China. Her application of integral geological principles to Chinese landscapes is evident and paved the way for her success. Her research was new, thorough, and very well explained. The concept explains and observes a topographic state which has come in contact with an abundant water source such as rain, tsunami, flood, river flow and more. The bedrock of such an area has faulting and other intrusions caused by various events of the past. This is justified and understood using the principle Nicholas Steno developed, cross-cutting relationships. Essentially, the water meanders and is absorbed into the cracks of said bedrocks, resulting in a topography heavily formed as a direct result of dissolving water underground. In her incredibly detailed and well-written book, “Karst in China,” she meticulously described why this phenomenon is accurately applicable to China, “Because China is part of the large mass of Asia, it is drained by some of the greatest rivers in the world . . . their tributaries, bring down enormous volumes of water and have been able to cut deep canyons into the karstic terrain.” She had such great interests in this phenomenon and thus moved to China so she could advance her research in her later days.[15]

Sweeting published more than seventy books and papers throughout her career, specialising in limestone and karst landscapes in which her travels took her to many sites around the world. These sites include: England, Ireland, Yugoslavia, Jamaica, Svalbard, Tasmania, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, China, Borneo, Malaysia, South Africa, Tibet.[10] Marjorie Sweeting has studied karsts of many different climates on how they are formed and classified them, ranging from sub-polar to humid tropical climates. The limestones were studied in the climates which they frequently appear in such as Australia, where there are larger extents of thick limestone.[16]

After retirement, Marjorie Sweeting continued her research in China which culminated in Karst in China: its Geomorphology and Environment, the manuscript being published posthumously in 1995, shortly after her death. It is the first comprehensive Western account of China's karst,[1][2] and was especially insightful because of its focus on limestone and varying limestone regions in China—the most important limestone region of the world—that was previously unstudied.[8] While it is an important study of karst formations in China, it has been criticized for not outright debunking the differing opinions of karst and other scientific studies within China.[8] A special issue of ‘Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie’ on ‘Tropical and subtropical karst’ was published in her honour in 1997. Marjorie had written over seventy different publications in her life[17] and was a very well-known and influential geomorphologist of her time.[9]

A major feature of Marjorie Sweeting’s career was her influence on generations of undergraduates and graduates. Many of her weekends and vacation weeks were filled with organized field trips for undergraduates, introducing them to caves and the pleasures of karstic landscapes.[9] Throughout her career at Oxford, she supervised over thirty graduate students, many of whom went on to make valuable contributions to the field of Geology, specifically in karst.[8] Notably, two of Sweeting’s students, Margaret Marker and Gillian E. Groom. Marker, published over 22 works and was granted the Gold Medal of the Society of South African Geographers in 1996. Similarly, Groom made contributions on topics like: the Spitsbergen glaciers, the raised shorelines of Gower, and karst limestone.[18] Like other women in the field of science at the time, academic and career advancement was not as rapid as it was for her male colleagues, and Sweeting exemplifies this as she was never promoted to professor despite her highly distinguished achievements and education.[15]

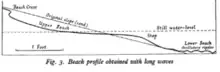

One of the many articles Sweeting published was Wave-Trough Experiments on Beach Profiles. In 1834, H.R. Palmer was the first person to study the connection between wave frequency and beach configuration. It was hard to distinguish whether the beach profiles were in fact due to wave frequency or just a result from natural conditions. As a result, experiments were performed in the Physical Geography Laboratory of the Cambridge Geography Department. Figure 3 shows the effects of long waves (low frequency) on beach configuration and figure 4 shows the effects of short waves (high frequency) on beach configuration.[19] Sweeting concluded that although many factors affect beach configuration such as the composition of the beach and the angle of which it lays at, frequency of waves does in fact play the biggest role. This is because there is a notable and evident relationship existing between wave action and beach profile. Rock and land configuration are heavily affected by catastrophic and uniform events. The wave model created by Sweeting showcases two beach profiles, destructive and constructive. The latter were high frequency waves and the former due to low. This was a crucial geological finding because using the landscape or configuration of the beach, past events could be revealed. Essentially, the contribution and correspondence of wave frequency with beach profile was incredible research, which enhanced Sweeting’s success in Geology [19]

Marjorie Sweeting officially retired in 1987 at the age of 67 and spent her last seven years with family, friends, and nature. Her title as an accomplished geomorphologist persisted.[7]

Achievements

Sweeting contributed largely to the field of karst. Her many awards included those of Gill Memorial Prize of the Royal Geographical Society (1955), Certificate of Merit of the National Speleological Society of America (1959), Honorary Member of the Cave Research Foundation of America (1969),[5] and the Busk Medal (1980).[20]

Sweeting was appointed a C.U.F. University Lectureship in 1953.[21] She was awarded the distinction of a personal readership in 1977.[21]

She obtained numerous awards in her lifetime. Upon passing, she had several dedicated in her honour. Aaron Wyld won the Marjorie Sweeting award for the best undergraduate geomorphological dissertation. His title awarded to him, “The hypsometry of glaciated mountain ranges with varying uplift and erosion rates.” His work was heavily focused on topography of glacial mountain ranges, similar to Sweeting’s work with landscapes. This showcases the long-lasting effect her legacy had in education, as well as on individuals who share a similar passion for earth sciences.[22]

Medalist of Palacky University, Czechoslovakia (1973), Honorary Fellow of the National Speleological Society of America (1976), first women to become a Chairman of the British Geomorphological Research Group (1973-1975)[23]

Due to her important and ground-breaking work in the field of geomorphology, The British Society for Geomorphology created "The Marjorie Sweeting Award" in 2008.[24] The award and prize of £200 goes to be the best undergraduate dissertation in the field of geomorphology at any university in the UK.

Other

Unable to continue her studies during World War II, Sweeting went to Denbigh, North Wales as a geography teacher at Howell's School.[25] At the end of the war, she was one of two women, along with Mabel Tomlinson, on the British national committee to advocate for the teaching of geology in high school.[26]

Marjorie used potholing as a way in which to introduce students to karst systems and caving.[25]

From 1977, when she led the initial expedition, Sweeting worked extensively on the karst landforms of China. There was plenty of scope – karst covers about one-seventh of the country, over five hundred thousand square kilometers. This was the first study of the karst regions of China by a western geomorphologist.[5]

Marjorie was acknowledged not only as an international expert on karst geomorphology, but also as a generous and enthusiastic mentor for generations of undergraduate and graduate students.[27]

For much of her career, Marjorie was one of only a small group of female physical geographers in Britain who fought hard and successfully to establish their international scientific reputation.[28]

Her father, George Scotland Sweeting, heavily fueled and directed Marjorie’s passion for geology as he himself was an ardent geologist. He lectured at the Imperial College in London, and as stated in Marjorie’s obituary, those close to her revealed she was determined to carry on her father’s legacy. For this reason, she deliberately studied and invested extensive time in geology and wished to be remembered as an earth scientist; a title she indefinitely earned as is evident from her accomplishments.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 Kennedy, Barbara (18 January 1995). "OBITUARIES: Marjorie Sweeting". The Independent.

- 1 2 Karst in China - Its Geomorphology and Environment | Marjorie M. Sweeting. Springer Series in Physical Environment. Springer. 1995. ISBN 9783642795220. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Goudie, Andrew (July 1995). "Obituaries: Marjorie Sweeting 1920-1994". Geographical Journal. 161 (2): 239–240.

- 1 2 3 4 Bull, Peter (23 September 2004). "Sweeting, Marjorie Mary (1920–1994)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56002. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 Gouldie, Andrew; Ford, Derek; Sugden, David (28 October 2016). "Dr. Marjorie Sweeting". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 12 (5): 445–451. doi:10.1002/esp.3290120502.

- ↑ Goudie, Andrew; Ford, Derek; Sugden, David (1987). "Dr. Marjorie Sweeting". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 12 (5): 445–451. Bibcode:1987ESPL...12..445G. doi:10.1002/esp.3290120502. ISSN 1096-9837.

- 1 2 3 4 Sweeting, Marjorie M. (1943). "Wave-Trough Experiments on Beach Profiles". The Geographical Journal. 101 (4): 163–168. doi:10.2307/1789676. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1789676.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sweeting, Marjorie Mary (1920–1994), Geomorphologist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56002. Retrieved 18 April 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 Goudie, A.S. (July 1995). "Obituaries: Marjorie Sweeting 1920-1994". The Geographical Journal. 161 (2): 239–240. JSTOR 3060006.

- 1 2 3 Hunter, Dana. "Marjorie Sweeting: "The Basis for a World Model of Karst"". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ↑ "Marjorie Sweeting". oxfordgeoscience. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ↑ Sweeting, Marjorie (1980). "The Geomorphology of Mulu: An Introduction". The Geographical Journal. 146 (1): 1–7. doi:10.2307/634064. JSTOR 634064.

- ↑ Campion, G., & Harrison. "A history of the China Caves Project. Cave and Karst Science, 41(2)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ SWEETING, MARJORIE. "International Association of Geomorphologists. Annales de géomorphologie, 39, 135 -".

- 1 2 Baigent, Elizabeth; Novaes, André Reyes (26 December 2019). Geographers: Biobibliographical Studies, Volume 38. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-12798-2.

- ↑ Jennings, Joseph Newell; Sweeting, Marjorie Mary (1963). The Limestone Ranges of the Fitzroy Basin, Western Australia. Dümmler.

- ↑ Sweeting, Marjorie (1973). Karst Landforms. London: Columbia University Press. p. 362.

- ↑ Hart, J. K. (2007). "The Role of Women in British Quaternary Science". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 281: 83–95. doi:10.1144/SP281.5. S2CID 130340558. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- 1 2 Sweeting, Marjorie M. (April 1943). "Wave-Trough Experiments on Beach Profiles". The Geographical Journal. 101 (4): 163–168. doi:10.2307/1789676. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1789676.

- ↑ Viles, H.A. (1996). "Obituary: Marjorie Sweeting 1920-1994". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 21: 429–432.

- 1 2 Goudie, Andrew; Ford, Derek; Sugden, David (1987). "Dr. Marjorie Sweeting". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 12 (5): 445–451. Bibcode:1987ESPL...12..445G. doi:10.1002/esp.3290120502. ISSN 1096-9837.

- ↑ "BSG Medal Winners' Webinar 2020 - Aaron Wyld - Marjorie Sweeting Dissertation Prize". YouTube.

- ↑ Goudie, A.S. (1995). "Obituaries: Marjorie Sweeting 1920-1994". The Geographical Journal. 161 (2): 239–240. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 3060006.

- ↑ "The Marjorie Sweeting Award | British Society for Geomorphology". www.geomorphology.org.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- 1 2 "Marjorie Sweeting". oxfordgeoscience. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ Burek, Cynthia V. (10 July 2020). "Mabel Elizabeth Tomlinson and Isabel Ellie Knaggs: two overlooked early female Fellows of the Geological Society". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 506 (1): 135–156. doi:10.1144/sp506-2019-235. ISSN 0305-8719. S2CID 225612062.

- ↑ Hunter, Dana (30 May 2013). "Marjorie Sweeting: "The Basis for a World Model of Karst"". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ↑ Hart, J.K. (2007). "The role of women in British Quaternary science". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 281: 83–95. doi:10.1144/SP281.5. Retrieved 5 October 2023.