Martin Rushent | |

|---|---|

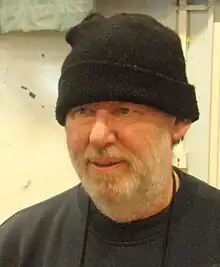

Rushent in February 2011 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Martin Charles Rushent[1] |

| Born | 11 July 1948 Enfield, Middlesex, United Kingdom |

| Origin | London, England |

| Died | 4 June 2011 (aged 62) Upper Basildon, Berkshire, United Kingdom |

| Genres | Punk rock, synthpop, new wave, electro, progressive rock[2] |

| Occupation(s) | Record producer, arranger |

| Instrument(s) | Synthesizer, vocals[2] |

| Years active | 1968–2011 |

| Labels | EMI, Virgin |

| Website | Martin Rushent Myspace |

Martin Charles Rushent (11 July 1948 – 4 June 2011)[1][3] was an English record producer, best known for his work with the Human League, the Stranglers and Buzzcocks.[4]

Early life

Rushent was born on 11 July 1948 in Enfield, Middlesex. His father was a car salesman. Rushent attended Minchenden Grammar School in Southgate, Middlesex.[1]

Career

Early career

Rushent's first experience in a recording studio was at EMI House in London's Manchester Square, when his school band (of which he was the lead singer) had the opportunity to record a demo.[5] After leaving school, Rushent, who had already experimented with his father's 4-track recorder, worked at a chemical factory before working for his father while applying for studio jobs. After numerous rejections, Rushent was employed by Advision Studios as a 35mm film projectionist. After approximately three months, Rushent began working in the audio department as a tape operator alongside Tony Visconti. He worked on sessions for Fleetwood Mac,[6] T.Rex, Yes, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Petula Clark, Jerry Lee Lewis and Osibisa.[7] Rushent stated that while at Advision, Jerry Lee Lewis threw a tantrum as Yes had been booked into the studio when he was not ready to leave, and chased the studio staff around the complex until they locked themselves in a different studio.[8]

Rushent progressed to senior assistant engineer, staff engineer, and eventually head engineer. He then began working freelance, where he built his reputation and was employed by United Artists (UA).[5] While with UA, Rushent recorded sessions alongside Martin Davies, recording artists such as Shirley Bassey and Buzzcocks, as well as convincing the company to sign the Stranglers provided that he produced the band's material. Rushent produced the group's Rattus Norvegicus, No More Heroes and Black and White albums and recorded demos for Joy Division, before tiring of his commute to London and leaving UA at the end of the 1970s.[1][5]

Synth-pop

Rushent expressed a desire to move away from guitar bands, and bought a Linn LM-1 drum machine,[8] Roland MC-8 Microcomposer and Jupiter-8 synthesiser to learn sequencing and synthesis techniques.[5] In 1980, Rushent set up his own studio, Genetic, designed by renowned studio designer Eddie Veale, with Synclavier and Fairlight CMI synthesisers[5] and an MCI console.[7] He spent £35,000 on air conditioning alone, and had a Mitsubishi Electric digital recorder costing £75,000.[5]

Rushent used his Roland equipment to record Pete Shelley's first solo album, Homosapien. Originally demos for the planned fourth Buzzcocks album, Shelley and Rushent deemed the recordings releasable, and Shelley was signed to Island Records. They were heard by Simon Draper of Virgin Records, who asked Rushent to produce for the Human League. Rushent's work on the group's 1981 album Dare earned him a BRIT Award in 1982 for Best British producer.[9]

Rushent's production on Dare frustrated the group's guitarist Jo Callis, as the only guitar on the album was used to trigger a gate on the synthesiser. Singer Susanne Sulley was also frustrated by the lengthy process of Rushent's synth programming. In 1983, Rushent walked out of his own studio after Sulley made an off-the-cuff comment toward him.[5]

Rushent also produced albums by Generation X, Altered Images and the Go-Go's in the 1980s.[10]

Rushent decided to take a break from production in the 1990s,[11] and sold his assets – including Genetic Studios. He briefly took up a consultancy position with Virgin, but retired from the industry to raise his children.[5]

Later career

Rushent returned to the music industry in the mid-1990s when he established Gush, a dance club on Greenham Common. The club's opening night was headlined by the Prodigy with support from Mad Professor and LTJ Bukem.[5] Rushent soon began redeveloping his interest in recording, and decided to catch up on the technological advances he had missed.[5]

Rushent built a home studio around a Mackie console, Alesis ADAT HD24 recorder and Cubase 5,[7] with which he produced music by the Pipettes,[9] Does It Offend You, Yeah?[8] and Killa Kela.[12] In 2005, he produced Hazel O'Connor's album Hidden Heart.[5] The following year, he was involved with the BBC Electric Proms when he recorded Enid Blitz, winners in the Brighton area, at a 15th-century manor house in Brentford, using a BBC truck as the control room.[5]

In 2007, Rushent produced the recording Cherry Vanilla by the (Fabulous) Cult of John Harley. The recording was used by the American singer and actress Cherry Vanilla in the launch of her autobiography Lick Me: How I Became Cherry Vanilla.[13]

At the time of his death, Rushent was working on a 30th anniversary version of Dare, remixed like Love and Dancing but using traditional musical instruments instead of synthesisers.[5][7]

Personal life

In 1972, Rushent married Linda Trodd, with whom he had three children – daughter Joanne and sons Tim and James.[1] They separated in the 1980s, and Rushent later married Ceri Davis, with whom he had a daughter named Amy.[1] Rushent lived with Ceri and Amy in the Berkshire village of Upper Basildon.[1][14] Rushent's son James is the lead singer of the dance-punk band Does It Offend You, Yeah?.[3] Rushent died on 4 June 2011, at his home in Berkshire. No cause was specified.[3][15]

Discography

| Year | Artist | Record | Type | Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Andrew Lloyd Webber | Jesus Christ Superstar | Studio album | Engineer | [2] |

| 1971 | T-Rex | Electric Warrior | Studio album | Engineer | [16] |

| Gentle Giant | Acquiring the Taste | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Compost | Compost | Studio album | Engineer, producer | [2] | |

| Stone the Crows | Teenage Licks | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Fleetwood Mac | Future Games | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| 1972 | Groundhogs | Hogwash | Studio album | Engineer | [2] |

| Gentle Giant | Three Friends | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Gentle Giant | Octopus | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Stone the Crows | Ontinuous Performance | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Shirley Bassey | I Capricorn | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| 1973 | Curved Air | Air Cut | Studio album | Producer | [17] |

| Chaos | Down At The Club/You Could Be My Girl | Studio single | Composer, producer | ||

| Johnny Harris | All to Bring You Morning | Studio album | Engineer, remixing | [2] | |

| Badger | One Live Badger | Live album | Engineer | [2] | |

| 1974 | Riff Raff | Original Man | Studio album | Engineer | [18] |

| The Sensational Alex Harvey Band | The Impossible Dream | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Snafu | Situation Normal | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Premiata Forneria Marconi | The World Became the World | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| 1975 | Danny Kirwan | Second Chapter | Studio album | Producer | [19] |

| Banco del Mutuo Soccorso | Banco | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Shirley Bassey | Good, Bad but Beautiful | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| Zzebra | Panic | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| 1976 | Roderick Falconer | New Nation | Studio album | Engineer | [2] |

| McKendree Spring | Too Young to Feel This Old | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| 1977 | The Stranglers | Rattus Norvegicus | Studio album | Producer | [5] |

| Shirley Bassey | You Take My Heart Away | Studio album | Engineer | [2] | |

| The Stranglers | No More Heroes | Studio album | Producer | [5] | |

| Téléphone | Téléphone | Studio album | Producer | [2] | |

| Trickster | Find the Lady | Studio album | Producer | ||

| 1978 | The Stranglers | Black and White | Studio album | Producer | [5] |

| Buzzcocks | Another Music in a Different Kitchen | Studio album | Producer | [20] | |

| Generation X | Generation X | Studio album | Producer | [21] | |

| Buzzcocks | Love Bites | Studio album | Producer | [16] | |

| 999 | Separates | Studio album | Producer | [22] | |

| Ian Gomm | Gomm with the Wind | Studio album | Producer | [2] | |

| Dr Feelgood | Private Practice | Studio album | Producer | [2] | |

| Ian Gomm | Summer Holiday | Studio album | Producer | [2] | |

| 1979 | The Stranglers | Live (X Cert) | Live album | Producer | [5] |

| Téléphone | Crache Ton Venin | Studio album | Producer | [23] | |

| Buzzcocks | A Different Kind of Tension | Studio album | Producer | [24] | |

| Jean-Jacques Burnel | Euroman Cometh | Studio album | Producer | [25] | |

| 1980 | Téléphone | Au Cœur De La Nuit | Studio album | Producer | [23] |

| Rachel Sweet | Protect the Innocent | Studio album | Producer | [26] | |

| 1981 | The Human League | Dare | Studio album | Producer | [5] |

| Pete Shelley | Homosapien | Studio album | Producer | [5] | |

| The Raybeats | Guitar Beat | Studio album | Producer | [27] | |

| Altered Images | Happy Birthday | Studio album | Engineer, producer | [2] | |

| Deke Leonard | Before Your Very Eyes | Studio album | Engineer, producer | [2] | |

| The dB's | Stands for Decibels | Studio album | Mixing | [2] | |

| 1982 | The Human League | Love and Dancing | Remix album | Producer | [5] |

| Altered Images | Pinky Blue | Studio album | Producer | [28] | |

| The Members | Uprhythm, Downbeat | Studio album | Producer | [29] | |

| 1983 | The Human League | Fascination! | E.P. | Producer | [5] |

| Pete Shelley | XL1 | Studio album | Producer | [30] | |

| Intaferon | Get Out Of London | Single/12" | Producer | [31] | |

| 1984 | The Human League | Hysteria | Studio album | Programming | [2] |

| Hazel O'Connor | Smile | Studio album | Producer | [2] | |

| The Go-Go's | Talk Show | Studio album | Engineer, producer | [32] | |

| 1985 | Associates | Perhaps | Studio album | Producer | [33] |

| 1988 | Do-Re-Mi | The Happiest Place in Town | Studio album | Producer | [32] |

| Associates | Heart of Glass | Single | Producer | [32] | |

| 1990 | The Human League | Heart Like a Wheel | Single | Producer | |

| Hard Corps | Metal + Flesh | Studio Album | Producer | ||

| 1993 | Flop | Whenever You're Ready | Studio album | Producer | |

| 1993 | The Beautiful Babies | Serenade | Studio album | Producer | |

| 1997 | Ian Gomm | Come On | Single | Producer | [32] |

| 2005 | Hazel O'Connor | Hidden Heart | Studio album | Producer | [5] |

| Carl Barat | Under the Influence | Studio album | Producer | [32] | |

| 2009 | Killa Kela | Amplified | Studio Album | Producer | [34] |

| 2010 | The Pipettes | Earth vs. The Pipettes | Studio album | Producer | [35] |

| 2011 | Does It Offend You, Yeah? | Don't Say We Didn't Warn You | Studio album | Producer | [32] |

| 2011 | The Pipettes | Boo Shuffle | Single | Producer | [32] |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Telegraph (7 June 2011). "Martin Rushent". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 "Martin Rushent". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 BBC News (5 June 2011). "Martin Rushent, influential music producer, dies at 63". BBC. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ↑ NME (2011). "Producer Martin Rushent dies aged 63". NME. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Flint, Tom (2007). "Martin Rushent: from Punk to Electro". Sound on Sound. SOS Publications Group. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ Topping, Alexandra (6 June 2011). "Prominent producer Martin Rushent dies aged 63". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Buskin, Richard (2010). "Human League "Don't You Want Me"". Sound on Sound. SOS Publications. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 Serck, Linda (2009). "Legendary producer Martin Rushent". Get Reading. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- 1 2 Serck, Linda (6 June 2011). "Martin Rushent's studio stories". BBC. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ Vaughan, Andrew (2011). "Top British Producer Dies". Gibson. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Dakeyne, Paul. "RIP Martin Rushent – Electronic Music Pioneer". DV247. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Chick, Jeremy (2009). "Killa Kela". Subba Cultcha. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ "MEDIA ACCESS on the official Cherry Vanilla website". Cherry-vanilla.com. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Serck, Linda (16 November 2009). "Pangbourne producer to the stars". BBC. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ Keepnews, Peter (13 June 2011). "Martin Rushent, Versatile Record Producer, Dies at 62". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Sweeting, Adam (7 June 2011). "Martin Rushent obituary". Guardian. UK. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Mota, Eduardo (1998). "Curved Air: Air Cut". Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Eyre, Tommy (1999). "Riff Raff". Alex Gitlin. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Carr, Roy; Clarke, Steve (1978). Fleetwood Mac: Rumours n' Fax. Harmony Books. p. 91. ISBN 0-517-53365-0.

- ↑ Shelley, Pete (2008). "Another Music In A Different Kitchen". Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ SPIN Magazine. 9 (5): 84. August 1993. ISSN 0886-3032.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 210. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- 1 2 Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 318. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- ↑ Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 96. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- ↑ Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 638. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- ↑ High Fidelity. Audiocom (1–6): 112. 1980.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Billboard Magazine. 93 (46): 90. November 1981. ISSN 0886-3032.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 8. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- ↑ Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 185. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin (2006). The encyclopedia of popular music. Oxford University Press. p. 401. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- ↑ Fellowes, Simon. "Music". Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Martin Rushent". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ Robbins, Ira A (1983). The Trouser Press guide to new wave records. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 28. ISBN 0-684-17943-1.

- ↑ "Killa Kela – Amplified". www.discogs.com. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ Eddy, Chuck (2010). "The Pipettes: Earth vs. the Pipettes". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 7 June 2011.