The Maryland State Colonization Society was the Maryland branch of the American Colonization Society, an organization founded in 1816 with the purpose of returning free African Americans to what many Southerners considered greater freedom in Africa. The ACS helped to found the colony of Liberia in 1821–22, as a place for freedmen.[1] The Maryland State Colonization Society was responsible for founding the Republic of Maryland in West Africa, a short lived independent state that in 1857 was annexed by Liberia. The goal of the society was "to be a remedy for slavery", such that "slavery would cease in the state by the full consent of those interested", but this end was never achieved, and it would take the outbreak of the Civil War to bring slavery to an end in Maryland.

Foundation

The Maryland Colonization Society was founded in 1827, and its first president was the wealthy planter Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who was himself a Marylander and a substantial slaveholder.[2] Although he supported the gradual abolition of slavery, he did not free his own slaves, perhaps fearing that they might be rendered destitute in the process.[3] Carroll introduced a bill for the gradual abolition of slavery in the Maryland senate but it did not pass.[4]

Many wealthy Maryland Planters were members of the MSCS. Among these were the Steuart family, who owned considerable estates in the Chesapeake Bay, including George H. Steuart, Major General of the Maryland Militia, who was on the board of Managers, along with his father James Steuart, who was vice-president, and his brother, the physician Richard Sprigg Steuart, also on the board of managers.[5]

In an open letter to John Carey in 1845, published in Baltimore by the printer John Murphy, Richard Sprigg Steuart set out his views on the subject of slavery in Maryland:

The colored man [must] look to Africa, as his only hope of preservation and of happiness ... it can not be denied that the question is fraught with great difficulties and perplexities, but ... it will be found that this course of procedure ... will ... at no very distant period, secure the removal of the great body of the African people from our State. The President of the Maryland Colonization Society points to this in his address, where he says "the object of Colonization is to prepare a home in Africa for the free colored people of the State, to which they may remove when the advantages which it offers, and above all the pressure of irresistible circumstances in this country, shall excite them to emigrate.[6]

The society proposed from the outset "to be a remedy for slavery", and declared in 1833:

Resolved, That this society believe, and act upon the belief, that colonization tends to promote emancipation, by affording the emancipated slave a home where he can be happier than in this country, and so inducing masters to manumit who would not do so unconditionally ... [so that] at a time not remote, slavery would cease in the state by the full consent of those interested.[7]

The society was founded in part as a response to the threat of slave rebellion, such as that of Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831. Among Southern whites, the prospect of a slave revolt was a constant concern. The Maryland State Colonization Society was seen as a remedy for slavery that would lead ultimately to emancipation by peaceful means.[8]

Republic of Maryland founded in Africa

In December 1831, the Maryland state legislature appropriated an annual US$10,000 for 26 years to transport free blacks and ex-slaves from the United States to Africa. The act appropriated funds of up to $20,000 a year, up to a total of $260,000, in order to commence the process of African colonization, a considerable expenditure by the standards of the time.[9][10] The legislature empowered the Maryland State Colonization Society to carry out the ends it had in view.[9] Most of the money would be spent on the colony itself, to make it attractive to settlers. Free passage was offered, plus rent, 5 acres (20,000 m2) of land to farm, and low interest loans which would eventually be forgiven if the settlers chose to remain in Liberia. The remainder was spent on agents paid to publicize the new colony.[11]

At the same time, measures were enacted to force freed slaves to leave the state, unless a court of law found them to be of such "extraordinary good conduct and character" that they might be permitted to remain. Any slave manumitted by his master must be reported to the authorities, and county clerks who did not do so could be fined.[10] It was in order to carry out this legislative purpose that the Maryland State Colonization Society was established.[12]

In 1832 the legislature placed new restrictions on the liberty of free blacks, in order to encourage emigration. They were not permitted to vote, serve on juries, or hold public office. Unemployed ex-slaves without visible means of support could be re-enslaved at the discretion of local sheriffs. By this means the supporters of colonization hoped to encourage free blacks to leave the state.[11]

John Latrobe, for two decades the president of the MSCS, and later president of the ACS, proclaimed that settlers would be motivated by the "desire to better one's condition", and that sooner or later "every free person of color" would be persuaded to leave Maryland.[13]

Settlement of Cape Palmas

Originally a branch of the American Colonization Society that had founded Liberia in 1822, the Maryland State Colonization Society decided to establish a new settlement of its own that could accommodate its emigrants. The first area to be settled was Cape Palmas, in 1834, somewhat south of the rest of Liberia.[14] The Cape is a small, rocky peninsula connected to the mainland by a sandy isthmus. Immediately to the west of the peninsula is the estuary of the Hoffman River. Approximately 21 km (15 mi) further along the coast to the east, the Cavalla River empties into the sea, marking the border between Liberia and the Côte d'Ivoire. It marks the western limit of the Gulf of Guinea, according to the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO).

Most of the settlers were freed African-American slaves and freeborn African-Americans primarily from the state of Maryland.[15] The colony was named Maryland In Africa (also known as Maryland in Liberia) on February 12, 1834.

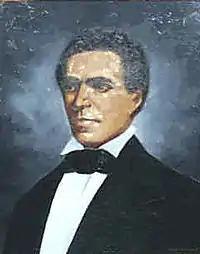

John Brown Russwurm

In 1836 the colony appointed its first black governor, John Brown Russwurm (1799–1851), who remained governor until his death. Russwurm encouraged the migration of African-Americans to Maryland-in-Africa and supported agriculture and trade.[16] He had begun his career as the colonial secretary for the American Colonization Society between 1830 and 1834. He also worked as the editor of the Liberia Herald, though he resigned his post in 1835 to protest America's colonization policies.

In 1838, a number of other African-American settlements on the west coast of Africa were united into the Commonwealth of Liberia, which then declared its independence in 1847. However, the colony of Maryland in Liberia colony remained independent, as the Maryland State Colonization Society wished to maintain its trade monopoly in the area. On February 2, 1841, Maryland-in-Africa was granted statehood, and became the State of Maryland. In 1847 the Maryland State Colonization Society published the Constitution and Laws of Maryland in Liberia, based on the United States Constitution.

Declaration of Independence and annexation by Liberia

On May 29, 1854, The State of Maryland declared its independence, naming itself the Republic of Maryland, or Maryland in Liberia,[17] with its capital at Harper. It held the land along the coast between the Grand Cess and San Pedro Rivers. However, the new republic would survive just three years as an independent state.

Soon afterward, local tribes including the Grebo and the Kru attacked the State of Maryland in retaliation for its disruption of the slave trade. Unable to maintain its own defense, Maryland appealed to Liberia, its more powerful neighbor, for help. President Roberts sent military assistance, and an alliance of Marylanders and Liberian militia troops successfully repelled the local tribesmen. However, it was now clear that the Republic of Maryland could not survive as an independent state, and on March 18, 1857 Maryland was annexed by Liberia, becoming known henceforth as Maryland County.

The coming of Civil War

By the 1850s few Marylanders still believed that Colonization was the solution to the problem of slavery.[18] By this time around one in every six Maryland families had slaves, but support for the institution of slavery was localized; varying according to its importance to the local economy.[18] Marylanders might agree in principle that slavery could and should be abolished, but turning theory into practice would prove elusive, and the overall numbers of slaves remained stubbornly high. Slavery was too deeply embedded into Maryland society for it to be voluntarily eradicated,[18] and the end would come only with war and bloodshed.

| Census Year | 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All States | 694,207 | 887,612 | 1,130,781 | 1,529,012 | 1,987,428 | 2,482,798 | 3,200,600 | 3,950,546 |

| Maryland | 103,036 | 105,635 | 111,502 | 107,398 | 102,994 | 89,737 | 90,368 | 87,189 |

Legacy and dissolution

The Maryland State Colonization did not achieve its goal of being a remedy for slavery, but it did leave a lasting legacy in Africa, in the form of its contribution to the creation of the modern state of Liberia. Ironically however, despite having been settled by freed slaves, Liberia would continue the slave trade well in the Twentieth Century. As late as the early 1930s the Liberian elite continued to traffic in human cargo from the country's interior, selling African labor on to Spanish plantations on the island of Fernando Po, where they were held in conditions akin to slavery. The former slaves had themselves become slave-traders.[20]

The American Colonization Society, of which the MSCS was a branch, was formally dissolved in 1964.

See also

References

- Andrews, Matthew Page, History of Maryland, Doubleday, New York (1929).

- Butcher, Tim, Chasing the Devil: the Search for Africa's Fighting Spirit, Chatto & Windus, London (2010).

- Flint, John E., et al, The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1790 to c. 1870 Cambridge University Press (1977) Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Freehling, William H., The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854 Retrieved March 12, 2010

- Hall, Richard, On Afric's Shore: A History of Maryland in Liberia, 1834-1857

- Latrobe, John H. B., p.125, Maryland in Liberia: a History of the Colony Planted By the Maryland State Colonization Society Under the Auspices of the State of Maryland, U. S. At Cape Palmas on the South - West Coast of Africa, 1833-1853 (1885). Retrieved Feb 16 2010

- Stebbins, Giles B., Facts and Opinions Touching the Real Origin, Character, and Influence of the American Colonization Society: Views of Wilberforce, Clarkson, and Others, published by Jewitt, Proctor, and Worthington (1853). Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Yarema, Allan E., American Colonization Society: An Avenue To Freedom? Retrieved September 2010

- Maryland Colonization Journal published by the Maryland State Colonization Society Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Discussion on American Slavery: Between George Thompson, Esq., Agent of the British and Foreign Society for the Abolition of Slavery Throughout the World, 17th of June, 1836, Published by Isaac Knapp, 46 Washington Street (1836). Retrieved February 16, 2010.

Notes

- ↑ Bateman, Graham; Victoria Egan, Fiona Gold, and Philip Gardner (2000). Encyclopedia of World Geography. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 161. ISBN 1-56619-291-9.

- ↑ Gurley, Ralph Randolph, Ed., p.251, The African Repository, Volume 3 Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Miller, Randall M., and Wakelyn, Jon L., p.214, Catholics in the Old South: Essays on Church and Culture Mercer University Press (1983). Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ Leonard, Lewis A. p.218, Life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton New York, Moffat, Yard and Company, (1918). Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ The African Repository, Volume 3, 1827, p.251, edited by Ralph Randolph Gurley Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Richard Sprigg Steuart, Letter to John Carey 1845, pp.10-11. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ Stebbins, Giles B., Facts and Opinions Touching the Real Origin, Character, and Influence of the American Colonization Society: Views of Wilberforce, Clarkson, and Others, published by Jewitt, Proctor, and Worthington (1853). Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ Yarema, Allan E., p.29, American Colonization Society: An Avenue To Freedom? Retrieved September 2010

- 1 2 Andrews, p.493

- 1 2 Freehling, William H., The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854, p.204 Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Freehling, William H., p.206, The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854 Retrieved March 12, 2010

- ↑ Latrobe, John H. B., p.125, Maryland in Liberia: a History of the Colony Planted By the Maryland State Colonization Society Under the Auspices of the State of Maryland, U. S. At Cape Palmas on the South - West Coast of Africa, 1833-1853, published in 1885. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ Freehling, William H., p.207, The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854 Retrieved March 12, 2010

- ↑ The African Repository, p.42 Retrieved March 2010

- ↑ Hall, Richard, On Afric's Shore: A History of Maryland in Liberia, 1834-1857.

- ↑ Lear, Alex (December 7, 2006). "Crossing the color line". The Community Leader. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Gurley, Ralph Randolph, Ed., The African Repository, Volume 3 Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Chapelle, Suzanne Ellery Greene, p.148, Maryland: A History of Its People Retrieved August 10, 2010

- ↑ "Total Slave Population in US, 1790–1860, by State". Archived from the original on August 22, 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ↑ Butcher, Tim, p. 21, Chasing the Devil: the Search for Africa's Fighting Spirit, Chatto & Windus, London (2010).

External links

- Gurley, Ralph Randolph, Ed., p.251, The African Repository, Volume 3 Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Proceedings of the Maryland Colonization Society at Niles' National Register, Volume 47 Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Brief History of Maryland in Liberia at www.buckyogi.com Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Brief History of Maryland in Liberia at www.worldstatesmen.org Retrieved February 16, 2010.