The United States is serviced by a wide array of public transportation, including various forms of bus, rail, ferry, and sometimes, airline services. Most established public transit systems are located in central, urban areas where there is enough density and public demand to require public transportation.[1] In more auto-centric suburban localities, public transit is normally, but not always, less frequent and less common. Most public transit services in the United States are either national, regional/commuter, or local, depending on the type of service. Sometimes "public transportation" in the United States is an umbrella term used synonymously with "alternative transportation", meaning any form of mobility that excludes driving alone by automobile.[2] This can sometimes include carpooling,[3] vanpooling,[4] on-demand mobility (i.e. Uber, Lyft, Bird, Lime),[5] infrastructure that is oriented toward bicycles (i.e. bike lanes, sharrows, cycle tracks, and bike trails),[6] and paratransit service.[7]

Most rail service in the United States is publicly funded at all tiers of government.[1] Amtrak, the national rail system, provides service across the entire contiguous United States. The frequency of Amtrak service varies depending on the size of the city, and its location along major rail routes. For example, cities such as New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. which are located along the busy Northeast Corridor, may see up to 50 Amtrak trains per day enter and leave their stations. This same corridor is the location of the only operating high speed rail network in the Americas: the Acela Express.[8] Other cities located on less frequent Amtrak lines, such as Dodge City, Kansas for instance, which is located on the Southwest Chief line may only have two trains daily. Regional rail services are primarily fixed on a major city or a state.[9] For example, the Long Island Rail Road services the Long Island suburbs of New York City, while the UTA FrontRunner serves as a regional rail service for the Wasatch Front of Utah.[9] These trains normally run throughout the entire day with service ranging from every 20 minutes during peak hours to every 30–45 minutes during off-peak hours. Other rail services that are regional in nature may only operate during rush hour. For example, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE), which services the Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C., only operates during the morning hours into Washington and the evening hours out of Washington. VRE does not operate at night nor on the weekends, and only has one train during the middle of the day. Several cities have light rail systems which operate generally in the core of the city and their surrounding suburbs. For instance, cities such as Kansas City, Norfolk, Boston, New Orleans, and Seattle have light rail or streetcar services that run every 10–15 minutes throughout their respective urban cores.

Presently, there is only one for-profit, private rail service in the United States, which is Brightline.[10] This service provides regular rail service from Fort Lauderdale to Miami, with a long term goal to connect Miami to Orlando, and become a statewide rail service for the state of Florida.

There are three common types of bus service in the United States: conventional bus systems, bus rapid transit (BRT), and intercity buses. Nearly every major city in the United States offers some form of bus service, with some being 24 hours a day. These buses run on flexible routes and make frequent stops, with a focus of provided accessible service to all tracts of a community. Bus rapid transit attempts to mimic the speed of a light rail system. Most BRT systems in the United States are in moderate sized cities or satellite cities, and serve as auxiliary routes for rail service. The primary difference between BRT in the United States and regular bus service is BRT often runs more frequent as has fewer stops, in order to make service quicker. BRT service generally has their own dedicated right of way and signal prioritization, which allows BRT vehicles to move faster than regular automobile traffic. Both BRT and conventional buses are usually publicly financed. Well-known examples of cities with popular BRT services in the United States include Cleveland, Miami, and Richmond. Most inter-city bus service is private for-profit ventures, although they normally used publicly subsidized motorways and highways. Examples of intercity bus service in the United States is Megabus and Greyhound, which are the two largest inter-city bus services in the United States.

Several coastal cities offer ferry service linking localities that are across large bodies of water where constructing road and railway bridges is not financially viable. Ferry service sometimes is pedestrian only but sometimes may offer platforms for automobiles and public transit vehicles depending on the vessel used.

Long-distance public transit which may be too far to feasibly travel by rail or bus, i.e. cross-country travel or travelling to U.S. territories is more regularly undertaken through airplanes.[1] Most airports in major regions are situated on the peripheries of major cities and publicly owned, while airline service itself is typically owned by for-profit corporations. In some cases, larger airports may operate their own rail, bus, and monorail systems that link various terminals together. Examples of this include Atlanta, Boston, Orlando, and Washington, D.C.'s airport.

History

After the rise of automobiles in the first half of the twentieth century, transit companies went out of business and ridership declined.[11][12]

Prior to 1950, the United States had a higher rate of public transport trips per capita than Germany. In 2010, Germany's per capita rate was about 7 times higher than the US. Even after accounting for demographics, socio-economics, and other factors, the rate was still 5 times higher. The low level of public transport usage in the United States compared to other developed Western nations has been relatively consistent according to a study covering 1980 through 2010. A 2012 comparison among 14 western countries found the US in last place in annual public transport trips per capita with 24 trips. The next to last country was the Netherlands with 51 trips and Switzerland was ranked first with 237. Reasons for the United States having a lower demand for public transport than Europe include lower density cities, tax policy, and the relative freedom of car use in American cities.[13]

Rail

As of March 2020, Amtrak provides public railway transportation on 35 lines, with services concentrated in the Pacific Northwest, Northeast, California, and the Midwest. Amtrak also operates its own long distance bus system to support its train network. The Auto Train is available from Washington, DC to Orlando, Florida that is capable of carrying along passengers’ vehicles.[14]

In 2021, Amtrak plans to deploy a fleet of 28 new Acela trainsets to serve the Northeast Corridor. The first of these trains are currently undergoing a nine month high-speed testing phase and will include personal comforts such as outlets, USB ports, improved Wi-Fi access, and an overall improvement in interior space design allowing 25 percent more passengers. The trains will travel between Boston and Washington D.C. multiple times a day, a route 3.5 million customers took in 2019. [15]

High-speed rail

Inter-city rail

Regional and commuter rail

Light rail and streetcars

Bus

Inter-city bus

In the mid-1950s more than 2,000 buses operated by Greyhound Lines, Trailways, and other companies connected 15,000 cities and towns. Passenger volume decreased as a result of expanding road and air travel, and urban decay that caused many neighborhoods with bus depots to become more dangerous. In 1960, American intercity buses carried 140 million riders. The rate decreased to 40 million by 1990, and continued to decrease until 2006.[16]

By 1997, intercity bus transportation accounted for only 3.6% of travel in the United States.[17] In the late 1990s, Chinatown bus lines that connected New York with Boston and Philadelphia's Chinatowns began operating. They became popular with non-Chinese college students and others who wanted inexpensive transportation, and between 1997 and 2007 Greyhound lost 60% of its market share in the northeast United States to the Chinatown buses. During the following decade, new bus lines such as Megabus and BoltBus emulated the Chinatown buses' practices of low prices and curbside stops on a much larger scale, both in the original Northeast Corridor and elsewhere, while introducing yield management techniques to the industry.[16][18][19]

By 2010 curbside buses' annual passenger volume had risen by 33% and they accounted for more than 20% of all bus trips.[16] One analyst estimated that curbside buses that year carried at least 2.4 billion passenger miles in the Northeast Corridor, compared to 1.7 billion passenger miles for Amtrak trains.[18] Traditional depot-based bus lines also grew, benefiting from what the American Bus Association called "the Megabus effect",[16] and both Greyhound and its subsidiary Yo! Bus, which competed directly with the Chinatown buses, benefited after the federal government shut several Chinatown lines down in June 2012.[19]

Between 2006 and 2014, American intercity buses focused on medium-haul trips between 200 and 300 miles; airplanes performed the bulk of longer trips and automobiles shorter ones. For most medium-haul trips curbside bus fares were less than the cost of automobile gasoline, and one tenth that of Amtrak. Buses are also four times more fuel-efficient than automobiles. Their Wi-Fi service is also popular; one study estimated that 92% of Megabus and BoltBus passengers planned to use an electronic device.[16] New lower fares introduced by Greyhound on traditional medium-distance routes and rising gasoline prices have increased ridership across the network and made bus travel cheaper than all alternatives.

Effective June 25, 2014, Greyhound reintroduced many much longer bus routes, including New York-Los Angeles, Los Angeles-Vancouver, and others, while increasing frequencies on existing long-distance and ultra-long-distance buses routes. This turned back the tide of shortening bus routes and puts Greyhound back in the position of competing with long-distance road trips, airlines, and trains. Long distance buses were to have Wi-Fi, power outlets, and extra legroom, sometimes extra recline, and were to be cleaned, refueled, and driver-changed at major stations along the way, coinciding with Greyhound's eradication of overbooking. It also represented Greyhound's traditional bus expansion over the expansion of curbside bus lines.[20]

Bus rapid transit

Bus rapid transit (BRT), also called a busway, is a bus-based public transport system designed to improve capacity and reliability relative to a conventional bus system.[21] Typically, a BRT system includes roadways that are dedicated to buses, and gives priority to buses at intersections where buses may interact with other traffic; alongside design features to improve accessibility and reduce delays caused by passengers boarding or leaving buses, or purchasing fares. BRT aims to provide "fast, comfortable, and cost-effective services at metro-level capacities".[21]

In the United States several moderately sized cities have BRT as an alternative to light rail due to perceived costs and political will. Notable examples of moderately sized cities with BRT as their fulcrum of public transportation include the Silver Line in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the GRTC Pulse in Richmond, Virginia, and the BusPlus in Albany, New York. Several satellite and suburban cities to larger cities also have bus rapid transit systems as secondary public transit services to light rail and commuter rail. For example, the Salt Lake City suburb of Murray has the planned Murray Taylorsville MAX BRT route. The Denver suburb of Fort Collins, and the Washington, D.C. suburbs of Arlington and Alexandria, Virginia contain the Metroway system.

Some major cities have their own BRT routes within city limits that function as their own rapid transit line, or as auxiliary routes to the rail lines in their respective city. In Cleveland, the HealthLine, which is considered a standard for BRT in the United States, serves most of the city. Minneapolis has the Red Line, and Los Angeles has the F Line, which does have plans to upgrade to light rail.

Commuter buses

Commuter bus systems are generally categorized as public transit, especially for large metropolitan transit networks. Usually these routes cover a long distance compared to most transit bus routes, but still short—usually 40 miles in one direction. An urban-suburban bus line generally connects a suburban area to the downtown core.

The vehicle can be something as simple as a merely refitted school bus (which sometimes already contains overhead storage racks) or a minibus. Often a suburban coach may be used, which is a standard transit bus modified to have some of the functionality of an interstate coach. The vehicles provide accommodation for the disabled (through a lift or ramp at the front), and thus has a few high-back seats, usually in the front, that can be folded up for wheelchairs. The rest of the seats are reclining upholstered seats and have individual lights and overhead storage bins. Because it is a commuter bus, it has some (but not much) standing room, stop-request devices, and a farebox. This model also has a bike rack at the front to accommodate two bicycles.

Suburban models in the United States are often used in Park-and-Ride services, and are very common in the New York City area, where New Jersey Transit Bus Operations is a major operator serving widespread bedroom communities.

Conventional buses

Paratransit

Ferry

Usage

The number of miles traveled by vehicles in the United States fell by 3.6% in 2008, while the number of trips taken on mass transit increased by 4.0%. At least part of the drop in urban driving can be explained by the 4% increase in the use of public transportation [22]

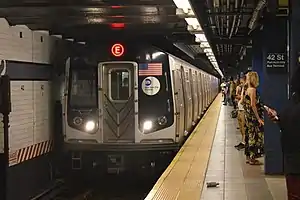

About one in every three users of mass transit in the United States and two-thirds of the nation's rail riders live in New York City and its suburbs.[23][24]

Cities

Most medium-sized cities have some form of local public transportation, usually a network of fixed bus routes. Larger cities often have metro rail systems (also known as heavy rail in the U.S.) and/or light rail systems for high-capacity passenger service within the urban area, and commuter rail to serve the surrounding metropolitan area. These include:

Funding

American mass transit is funded by a combination of local, state, and federal agencies. At the federal level, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) provides financial assistance and technical assistance to state governments and local transit providers. From FY 2005 to FY 2009, the funding scheme for the FTA was regulated by the SAFETEA-LU bill, which appropriated $286.4 billion in guaranteed funding.[25] The FTA awards grants through several programs, such as the New Starts program and Transit Investments for Greenhouse Gas and Energy Reduction (TIGGER) program.

Historically, public transportation in the United States has been reliant on private investments. Congress first authorized money for public transport under the Urban Mass Transportation Act (UMTA) of 1964, with $150 million per year. Under the UMTA of 1970, this amount rose to $3.1 billion per year. Since then, ridership has risen from 6.6 billion in the mid-1970s to 10.2 billion today. None of the major transit systems in the US generate enough revenue to cover their operating expenses, but the those with the highest percentages include the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District with 71.6 percent and the Washington, DC metropolitan rail system with 62.1 percent.[11]

The most widely used source for public transport funds in the United States is general sales tax. Whereas most countries usually don’t put motoring taxes to a specific use, there are instances in the United States where this revenue is earmarked to fund public transport. For example, bridge tolls on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco are used to subsidize local bus and ferry Services. In contrast to other Western countries, public transport use is low and mostly by the poor, which makes it harder to raise additional funds. In response to reductions in Federal support for public transport, individual states and cities sometimes levy local taxes to maintain their transit systems. [26]

Legislation

On June 26, 2008, the House passed the Saving Energy Through Public Transportation Act (H.R. 6052),[27] which gives grants to mass transit authorities to lower fares for commuters pinched at the pump and expand transit services. The bill also:

- Requires that all Federal agencies offer their employees transit pass transportation fringe benefits. Federal agencies within the National Capital Region have successful transit pass benefits programs.

- Increases the Federal cost-share of grants for construction of additional parking facilities at the end of subway lines from 80 to 100 percent to cover an increase in the number of people taking mass transit.

- Creates a pilot program for vanpool demonstration projects in urban and rural areas.

- Increases federal help for local governments to purchase alternative fuel buses, locomotives and ferries from 90 to 100 percent.

Advanced public transportation systems

Advanced public transportation systems (or APTS) is an Intelligent Vehicle Highway Systems, or IVHS, technology that is designed to improve transit services through advanced vehicle operations, communications, customer service, energy efficiency, air pollution reduction and market development.

Opposition to public transport

Growth in public transport amenities is sometimes opposed in the United States, on the grounds that public transport is allegedly a potential conduit for crime, from one area into another.[28]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Black, Alan (1995). Urban mass transportation planning. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070055575. OCLC 31045097.

- ↑ Haring, Joseph E.; Slobko, Thomas; Chapman, Jeffrey (January 1976). "The impact of alternative transportation systems on urban structure". Journal of Urban Economics. 3: 14–30. doi:10.1016/0094-1190(76)90055-3.

- ↑ Correia, Gonçalo; Viegas, José Manuel (2011-02-01). "Carpooling and carpool clubs: Clarifying concepts and assessing value enhancement possibilities through a Stated Preference web survey in Lisbon, Portugal". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 45 (2): 81–90. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2010.11.001. ISSN 0965-8564.

- ↑ Bush, Leon R. Vanpool Implementation in Los Angeles: Commute-a-van. Aerospace Corporation, 1975.

- ↑ Pavone, Marco; Morton, Daniel; Frazzoli, Emilio; Zhang, Rick; Treleaven, Kyle; Spieser, Kevin (2014), "Toward a Systematic Approach to the Design and Evaluation of Automated Mobility-on-Demand Systems: A Case Study in Singapore", Road Vehicle Automation, Lecture Notes in Mobility, Springer, Cham, pp. 229–245, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05990-7_20, hdl:1721.1/82904, ISBN 9783319059891

- ↑ Hegger, Ruud (May 14, 2007). "Public Transport and Cycling: Living Apart or Together?". Transportation Research Board. 56: 38–41 – via The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

- ↑ Cervero, Robert; Round, Alfred (1996). "Future Ride: Adapting New Technologies to Paratransit in the United States".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "ACELA High-Speed Rail Network System". Railway Technology. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

- 1 2 "Multi-Scalar Analysis of Transit-Oriented Development for New Start Commuter Rail". Transportation Research Board. January 12, 2016 – via The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

- ↑ "Branson buys into Brightline". Railway Age. 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

- 1 2 Mathur, S. (2016). Innovation in public transport finance: property value capture. Place of publication not identified: Routledge.

- ↑ Zipper, David (27 April 2023). "Anatomy of an 'American Transit Disaster'". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ↑ Buehler, R., & Pucher, J. (2012). Demand for Public Transport in Germany and the USA: An Analysis of Rider Characteristics. Transport Reviews, 32(5), 541–567. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2012.707695

- ↑ "Amtrak Routes & Stations." Amtrak Routes & Stations, www.amtrak.com/train-routes.

- ↑ Palma, Kristi. "Amtrak to Begin High-Speed Testing of Its New Acela Trains, Coming in 2021." Boston.com, The Boston Globe, 19 Feb. 2020, www.boston.com/travel/travel/2020/02/19/amtrak-acela-trains-high-speed-testing.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Austen, Ben (2011-04-07). "The Megabus Effect". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ↑ Transportation Statistics Annual Report (1997) edited by Marsha Fenn, page 7

- 1 2 O'Toole, Randal (29 June 2011). "Intercity Buses: The Forgotten Mode". Policy Analysis (680).

- 1 2 Schliefer, Theodore (2013-08-08). "Bus travel is picking up, aided by discount operators". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "Greyhound System Timetable June 25th, 2014". Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- 1 2 "What is BRT?". Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. 2014-07-25.

- ↑ "EERE News: U.S. Transit Use up, Driving Down in 2008". Archived from the original on 2009-05-04. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ "The MTA Network: Public Transportation for the New York Region". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on 2009-06-03. Retrieved 2006-05-17.

- ↑ Pisarski, Alan (October 16, 2006). "Commuting in America III: Commuting Facts" (PDF). Transportation Research Board. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

- ↑ SAFETEA-LU Implementation Archived 2010-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Transit Administration.

- ↑ Enoch, M., Nijkamp, P., Potter, S., & Ubbels, B. (2014). Unfare Solutions Local Earmarked Charges to Fund Public Transport. Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor and Francis.

- ↑ Archived 2008-10-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Jaffe, Eric (December 11, 2014). "The Myth That Mass Transit Attracts Crime Is Alive in Atlanta". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

Further reading

- Cheape, Charles W., Moving the masses: urban public transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, 1880–1912, Harvard University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-674-58827-4

- Bloom, Nicholas D., The Great American Transit Disaster: A Century of Austerity, Auto-Centric Planning, and White Flight, University of Chicago Press, 2023. ISBN 9780226824413