| Lidice massacre | |

|---|---|

Lidice in 1942 after its destruction by the Nazis | |

| Location | Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia |

| Date | 10 June 1942 |

| Target | Czechs |

Attack type | Genocidal massacre[1] |

| Weapons | Firearms |

| Deaths | 340 including 82 children exterminated later after transfer to Chełmno |

| Perpetrators | |

| Motive | Reprisal attack following the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich |

The Lidice massacre (Czech: Vyhlazení Lidic) was the complete destruction of the village of Lidice in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which is now a part of the Czech Republic, in June 1942 on orders from Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and acting Reichsprotektor Kurt Daluege, successor to Reinhard Heydrich. It has gained historical attention as one of the most documented instances of German war crimes during the Second World War, particularly given the deliberate killing of children.

In reprisal for the assassination of Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich in the late spring of 1942,[2] all 173 men from the village who were over 15 years of age were executed on 10 June 1942.[3] A further 11 men from the village who were not present at the time were later arrested and executed soon afterwards, along with several others who were already under arrest.[3] Out of a total 503 inhabitants, 307 women and children were sent to a makeshift detention center in a Kladno school. Of these, 184 women and 88 children were deported to concentration camps; 7 children who were considered racially suitable and thus eligible for Germanisation were handed over to SS families, and the rest were sent to the Chełmno extermination camp, where they were gassed to death.[3][4]

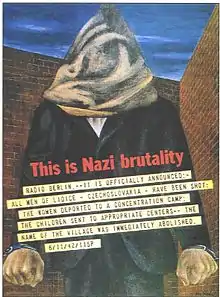

The Associated Press, quoting German radio transmissions which it received in New York, said: "All male grownups of the town were shot, while the women were placed in a concentration camp, and the children were entrusted to appropriate educational institutions."[5] Approximately 340 people from Lidice were murdered in the German reprisal (192 men, 60 women and 88 children). After the war ended, only 143 women and 17 children returned.[3][6][7][8][9]

Nazi propaganda openly and proudly announced the events at Lidice in direct contrast to the disinformation and secrecy involved with other crimes against civilian populations, with intense outrage occurring among Allied nations and particularly Anglosphere countries. The history has been depicted in multiple forms of media since the end of the conflict. Examples include the internationally known drama film Operation Daybreak and the composer Bohuslav Martinů composed orchestral work Memorial to Lidice.

In socio-political and legal terms, the event is known as a notable example of a "genocidal massacre", which describes an act of mass killing against a specific community of victims done in step of a larger and more violent campaign enacting hatred against broader groups. This is a part of the larger topic of genocide studies.[1]

Background

Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

From 27 September 1941, SS-Obergruppenführer and General of Police Reinhard Heydrich had been acting as Reichsprotektor of the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.[10] This area of the former state of Czechoslovakia had been occupied by Nazi Germany since 5 April 1939.[10]

On the morning of 27 May 1942, Heydrich was being driven from his country villa at Panenské Břežany to his office at Prague Castle. When he reached the Kobylisy area of Prague, his car was attacked (on behalf of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile) by the Slovak and Czech soldiers Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš.[3] These men, who had been part of a team trained in Great Britain, had parachuted into Bohemia in December 1941 as part of Operation Anthropoid.

After Gabčík's Sten gun jammed, Heydrich ordered his driver, SS-Oberscharführer Klein, to stop the car. When Heydrich stood up to shoot Gabčík, Kubiš threw a modified anti-tank grenade at Heydrich's car.[11] The resulting explosion wounded both Heydrich and Kubiš.[12] Heydrich sent Klein to chase Gabčík on foot and, in an exchange of fire, Gabčík shot Klein in the leg below the knee. Kubiš and Gabčík managed to escape the scene.[13] A Czech woman went to Heydrich's aid and flagged down a delivery van. He was placed on his stomach in the back of the van and taken to the emergency room at Bulovka Hospital. A splenectomy was performed, and the chest wound, left lung, and diaphragm were all debrided. Himmler ordered Karl Gebhardt to fly to Prague to assume care. Despite a fever, Heydrich's recovery appeared to progress well. Hitler's personal doctor Theodor Morell suggested the use of the new antibacterial drug sulfonamide, but Gebhardt thought that Heydrich would recover and declined the suggestion. On 4 June Heydrich died from septicaemia caused by pieces of horse hair from the upholstery and his clothing entering his body when the bomb exploded.[14]

Reprisals

Late in the afternoon of 27 May, SS-Gruppenführer Karl Hermann Frank proclaimed a state of emergency and placed a curfew in Prague.[15] Anyone who helped the attackers was to be executed along with their families.[15] A search involving 21,000 men began and 36,000 houses were checked.[15] By 4 June, 157 people had been executed as a result of the reprisals but the assassins had not been found and no information was forthcoming.[15]

The eulogies at Heydrich's funeral in Berlin were not yet over when, on 9 June, the decision was made to "make up for his death". Frank, Secretary of State for the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, reported from Berlin that the Führer had commanded the following concerning any village found to have harbored Heydrich's killers:[16]

- Execute all men

- Transport all women to a concentration camp

- Gather the children suitable for Germanisation, then place them in SS families in the Reich and bring the rest of the children up in other ways

- Burn down the village and level it entirely

Massacre

Men

Horst Böhme, the SiPo chief for the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, immediately acted on the orders.[2] Members of the Ordnungspolizei and SD (Sicherheitsdienst) surrounded the village of Lidice, blocking all avenues of escape.[17] The Nazi regime chose this village because its residents were suspected of harbouring local resistance partisans and were falsely associated with aiding Operation Anthropoid team members.[18][19]

All men of the village were rounded up and taken to the farm of the Horák family on the edge of the village. Mattresses were taken from neighbouring houses where they were stood up against the wall of the Horáks' barn to prevent ricochets.[16] The shooting of the men commenced at about 7:00 am. At first the men were shot in groups of five, but Böhme thought the executions were proceeding too slowly and ordered that ten men be shot at a time. The dead were left lying where they fell. This continued until the afternoon hours when there were 173 dead.[15] Another 11 men who were not in the village that day were arrested and murdered soon afterwards as were eight men and seven women already under arrest because they had relations serving with the Czechoslovak armies in exile in the United Kingdom.[16] Only three male inhabitants of the village survived the massacre, two of whom were in the Czechoslovak Air Force and stationed in England at the time.[20] The only adult man from Lidice actually in Czechoslovakia who survived this atrocity was František Saidl (1887–1961), the former deputy-mayor of Lidice who had been arrested at the end of 1938 because on 19 December 1938 he accidentally killed his son Eduard Saidl. He was imprisoned for four years and had no idea about this massacre. He found out when he returned home on 23 December 1942. Upon discovering the massacre, he was so distraught he turned himself in to SS officers in the nearby town of Kladno, confessed to being from Lidice, and even said he approved of the assassination of Heydrich. Despite confirming his identity, the SS officers simply laughed at him and turned him away, and he went on to survive the war.[20]

Women and children

A total of 203 women and 105 children were first taken to Lidice village school, then the nearby town of Kladno and detained in the grammar school for three days. The children were separated from their mothers and four pregnant women were sent to the same hospital where Heydrich died, forced to undergo abortions and then sent to different concentration camps. On 12 June 1942, 184 women of Lidice were loaded on trucks, driven to Kladno railway station and forced into a special passenger train guarded by an escort. On the morning of 14 June, the train halted on a railway siding at the concentration camp at Ravensbrück. The camp authorities tried to keep the Lidice women isolated, but were prevented from doing so by other inmates. The women were forced to work in leather processing, road building, textile and ammunition factories.[21]

Eighty-eight Lidice children were transported to the area of the former textile factory in Gneisenau Street in Łódź. Their arrival was announced by a telegram from Horst Böhme's Prague office which ended with: the children are only bringing what they wear. No special care is desirable. The care was minimal and they suffered from a lack of hygiene and from illnesses. By order of the camp management, no medical care was given to the children. Shortly after their arrival in Łódź, officials from the Central Race and Settlement branch chose seven children for Germanisation.[22] The few children considered racially suitable for Germanisation were handed over to SS families.[16]

The furor over Lidice caused some hesitation over the fate of the remaining children but in late June Adolf Eichmann ordered the massacre of the remainder of the children.[22] However, Eichmann was not convicted of this crime at his trial in Jerusalem, as the judges deemed that "... it has not been proven to us beyond reasonable doubt, according to the evidence before us, that they were murdered."[23] On 2 July, all of the remaining 82 Lidice children were handed over to the Łódź Gestapo office, who sent them to the Chelmno extermination camp 70 kilometres (43 miles) away, where they were gassed to death in Magirus gas vans. Out of the 105 Lidice children, 82 were murdered in Chełmno, six were murdered in the German Lebensborn orphanages and 17 returned home.

Lidice

The village was set on fire and the remains of the buildings destroyed with explosives. All the animals in the village—pets and beasts of burden—were slaughtered as well. Even those buried in the town cemetery were not spared; their remains were dug up, looted for gold fillings and jewellery, and destroyed.[3] A 100-strong German work party was then sent in to remove all visible remains of the village, re-route the stream running through it and the roads in and out. They then covered the entire area the village had occupied with topsoil and planted crops, and set up a barbed-wire fence around the site which had notices reading, in both Czech and German, "Anyone approaching this fence who does not halt when challenged will be shot". A film was made of the process by Franz Treml, a collaborator with German intelligence. Treml had run a Zeiss-Ikon shop in Lucerna Palace in Prague and after the Nazi occupation, he became a film adviser for the Nazi Party.[24]

Further reprisals

The small Czech village of Ležáky was destroyed two weeks after Lidice, when Gestapo agents found a radio transmitter there that had belonged to an underground team who parachuted in with Kubiš and Gabčík. All 33 adults (both men and women) from the village were shot.[25] The children were sent to concentration camps or "Aryanised". The death toll resulting from the effort to avenge the death of Heydrich is estimated at over 1,300 people.[25] This count includes relatives of the partisans, their supporters, Czech elites suspected of disloyalty and random victims like those from Lidice.

Commemorations

International response

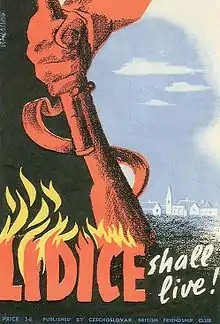

Nazi propaganda had openly and proudly announced the events in Lidice, unlike other massacres in occupied Europe which were kept secret.[26] The information was instantly picked up by Allied media. After the massacre Winston Churchill proposed destroying three German villages with incendiary bombing for every village destroyed in reprisals by the Wehrmacht. Anthony Eden, Leo Amery, and Ernest Bevin were supportive of the idea, but Archibald Sinclair, Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison, and Stafford Cripps convinced him that it would waste resources and open the risk to similar Luftwaffe reprisals against British communities.[27] In September 1942, coal miners in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, in Great Britain led by Barnett Stross, a doctor, who in 1945 became a local MP, founded the organisation Lidice Shall Live to raise funds for the rebuilding of the village after the war.[21]

Soon after the razing of the village, towns and quarters (neighbourhoods) in various countries were renamed, San Jerónimo Lídice in Mexico City, Barrio Obrero de Lídice[28] (workers quarter of Lidice) and its hospital in Caracas, Venezuela, Lídice de Capira in Panama and towns in Brazil so that the name would live on in spite of Hitler's intentions. A neighbourhood in Crest Hill, Illinois, U.S., was renamed from Stern Park to Lidice. There is a shrine at Lidice park on Prairie Avenue in Crest Hill; the original shrine was at the end of Kelly Avenue at Elsie Street. A square in the English city of Coventry, devastated by Luftwaffe bombing, is named after Lidice. An alley in a very crowded area of downtown Santiago, Chile, is named after Lidice and one of the buildings has a small plaque that explains its tragic story. A street in Sofia, Bulgaria, is named to commemorate the massacre and the Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin, U.S., was built in memory of the village.

In the wake of the massacre, Humphrey Jennings directed The Silent Village (1943), using amateur actors from a Welsh mining village, Cwmgiedd, near the small South Wales town of Ystradgynlais. An American film was made in 1943 called Hitler's Madman, but it contained a number of inaccuracies in the story. A more accurate British film, Operation Daybreak, starring Timothy Bottoms as Kubiš, Martin Shaw as Čurda and Anthony Andrews as Gabčík, was released in 1975.

American poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote a book-length verse play on the massacre, The Murder of Lidice, which was excerpted in the 17 October 1942, edition of Saturday Review,[29] a larger version of which was published in the 19 October 1942 Life magazine, and published in full as a book later that year by Harper.[30]

There is a memorial sculpture and small information panel commemorating the Lidice massacre, in Wallanlagen Park in Bremen, Germany.

Local response and the new Lidice

Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů composed his Memorial to Lidice, an 8-minute orchestral work, in 1943, as a response to the massacre. The piece quotes from the Czech St Wenceslas Chorale and in the climax of the piece, the opening notes (dot-dot-dot-dash = V in Morse code) of Beethoven's 5th Symphony.[31]

.jpg.webp)

Women from Lidice who survived imprisonment at Ravensbrück returned after the Second World War and were rehoused in the new village of Lidice that was built overlooking the original site. The first part of the new village was completed in 1949. Two men from Lidice were in the United Kingdom serving in the Royal Air Force at the time of the massacre. After 1945 Pilot Officer Josef Horák and Flight Lieutenant Josef Stříbrný returned to Czechoslovakia to serve in the Czechoslovak Air Force.

After the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état the new Communist Party government would not allow them to apply to be housed in the new Lidice, because they had served in the forces of one of the western powers. Horák and his family returned to Britain and the RAF; he died in a flying accident in December 1948.[32]

A sculpture from the 1990s by Marie Uchytilová overlooks the site of the old village of Lidice. Entitled "The Memorial to the Children Victims of the War" it comprises 82 bronze statues of children (42 girls and 40 boys) aged 1 to 16, to honour the children who were murdered at Chełmno in the summer of 1942. A cross with a crown of thorns marks the mass grave of the Lidice men. Overlooking the site is a memorial area flanked by a museum and a small exhibition hall.[33] The memorial area is linked to the new village by an avenue of linden trees. In 1955 a "Rosarium" of 29,000 rose bushes was created beside the avenue of lindens overlooking the site of the old village. In the 1990s the Rosarium was neglected but after 2001 a new Rosarium with 21,000 bushes was created.[34]

See also

- Lidice (also known as Fall of the Innocent), a 2011 Czech drama film

References

- 1 2 Genocide as a Concept in Law and Scholarship: A Widening Rift? Archived 2023-09-06 at the Wayback Machine. Kjell Magnusson.

- 1 2 Gerwarth 2011, p. 280.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jan Kaplan and Krystyna Nosarzewska, Prague: The Turbulent Century p. 241

- ↑ Fraňková, Ruth (23 March 2021). "In memoriam: Marie Šupíková, one of the last survivors of the Lidice massacre". Radio Prague. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ The New York Times, Nazis Blot Out Czech Village; Kill All Men, Disperse Others, 11 June 1942

- ↑ Wechsberg, Joseph (1 May 1948). "The Children of Lidice". The New Yorker. p. 34. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ Solly, Meilan (12 September 2018). "The Lost Children of the Lidice Massacre". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ Tait, Robert (14 March 2020). "Czech village razed by Hitler at heart of row on truth and history". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ "Lidice, 79 Years Later". Prague Morning. 9 June 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- 1 2 Jan Kaplan and Krystyna Nosarzewska, Prague: The Turbulent Century p. 214

- ↑ Michel, Wolfgang, Britische Spezialwaffen 1939–1945: Ausrüstung für Eliteeinheiten, Geheimdienst und Widerstand, p. 72 ISBN 3-8423-3944-5

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 145–47.

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 147.

- ↑ Burian, Michal; Aleš (2002). "Assassination – Operation Arthropoid, 1941–1942" (PDF). Ministry of Defence of the Czech Republic. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jan Kaplan and Krystyna Nosarzewska, Prague: The Turbulent Century p. 239

- 1 2 3 4 Jan Kaplan and Krystyna Nosarzewska, Prague: The Turbulent Century p. 246

- ↑ Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (2012-06-08). "NS-Massaker : Nicht die SS, Polizisten mordeten in Lidice – Nachrichten Kultur – Geschichte". Die Welt. Welt.de. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ↑ Williamson, Gordon, Loyalty is my Honor p. 87

- ↑ Wechsberg, Joseph (24 June 1948). "The Love Letter That destroyed Lidice". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 20. Retrieved 25 May 2016 – via Google News Archive.

- 1 2 "The Lidice massacre after 65 years". 8 June 2007. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- 1 2 Phillips, Russell (2016). A Ray of Light: Reinhard Heydrich, Lidice, and the North Staffordshire Miners. Shilka Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-0995513303. Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- 1 2 Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p. 254 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ↑ Arendt, Hannah 1963 "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil" p. 207

- ↑ "Remains of Lidice in June 1942" (film). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- 1 2 Gerwarth 2011, p. 285.

- ↑ "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 8" Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine. 22 February 1946

- ↑ Roberts, Andrew (2009). Masters and Commanders: The Military Geniuses Who Led the West to Victory in World War II. London: Penguin Books. pp. 182–83. ISBN 978-0-141-02926-9 – via Archive Foundation.

- ↑ "Lídice (Caracas)". wikimapia.org. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ↑ Edna St. Vincent Millay; Franklin P Adams (intro.). "The Murder of Lidice": 3–5.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Millay, Edna St. Vincent. The Murder of Lidice. New York: Harper: 1942.

- ↑ Mihule J. Liner note to Supraphon CD 11 1931-2 001, which includes the work played by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Karel Ančerl.

- ↑ David Vaughan. "Josef Horak, a twentieth-century Czech hero" Archived 2008-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. Český Rozhlas Archived 2001-03-06 at the Wayback Machine. 24 July 2002.

- ↑ "Lidice Memorial: History". Lidice-memorial.cz. 10 July 1945. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ↑ "The History of Lidice Memorial Before Year 2000" Archived 2008-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. Lidice Memorial Archived 2003-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

Books

- Gerwarth, Robert (2011). Hitler's Hangman: The Life of Heydrich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11575-8.

- Jan Kaplan and Krystyna Nosarzewska, Prague: The Turbulent Century, Koenemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Koeln, (1997) ISBN 3-89508-528-6

- Joan M. Wolf: Someone Named Eva. 2007. ISBN 0-618-53579-9

- Eduard Stehlík: Lidice, The Story of a Czech Village. 2004. ISBN 80-86758-14-1

- Zena Irma Trinka: A little village called Lidice: Story of the return of the women and children of Lidice. International Book Publishers, Western Office, Lidgerwood, North Dakota, 1947.

- Maureen Myant: The Search. Alma Books, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84688-103-9

- Williams, Max (2003). Reinhard Heydrich: The Biography, Volume 2 – Enigma. Church Stretton: Ulric Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9537577-6-3.

- Williamson, Gordon (1995). Loyalty is my Honor. Motorbooks International. ISBN 0-7603-0012-7.

External links

Media related to Lidice massacre at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lidice massacre at Wikimedia Commons- (in English) Remains of Lidice in June 1942 (film at U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- Hitler's Madman at IMDb – A fictional account of the death of Reinhard Heydrich and the reprisals against Lidice.

- The Silent Village at IMDb – The true story of the massacre of a small Czech village by the Nazis is retold as if it happened in Wales.

- Alan Heath: Fate of the children of Lidice on YouTube

- (in English, Czech, German, and Russian) Lidice Memorial

- (in Czech) Official Website of Municipality

- (in Czech) Recent (since 1990s) search for missing children

- (in Czech) Photo series about destruction of Lidice by Reichsarbeitsdienst

- (in Czech) "Lidice" film Official website, directed by Petr Nikolaev The first ever Czech-made feature film about the destruction of Lidice, which was available on May 18, 2020 at Amazon Prime under the title "Fall of the Innocent".

- Lidice Commemorative Gathering Fenton 2010 – Pics Video and Listen again Lidice commemorative gathering pics video and listen again Archived 2016-11-23 at archive.today

- Lidice & Stoke-on-Trent for Schools – a free Powerpoint presentation suitable for teaching the Lidice atrocity in schools

- A free copy of Vic Carnall's Opus 17, a piano solo entitled "In Memoriam: the Village of Lidice (Czechoslovakia / June, 1942)".

- "A tree remembers" (official page) (2018) – A documentary about the massacre of Lidice, levelled and – literally – eradicated by the Nazis in retaliation for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich.