Hannah Arendt | |

|---|---|

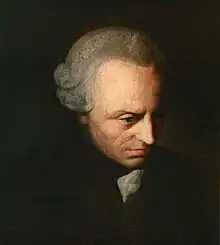

Arendt in 1933 | |

| Born | Johanna Arendt 14 October 1906 Linden, Province of Hanover, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 4 December 1975 (aged 69) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Bard College |

| Other names | Hannah Arendt Bluecher |

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | |

| Notable work | List

|

| Spouses | |

| Relatives |

|

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | List

|

| Doctoral advisor | Karl Jaspers[6] |

Main interests | Political theory, theory of totalitarianism, philosophy of history, theory of modernity |

Notable ideas | List

|

| Signature | |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Hannah Arendt (/ˈɛərənt, ˈɑːr-/,[10][11] US also /əˈrɛnt/,[12] German: [ˌhana ˈaːʁənt] ⓘ;[13] born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was an American historian and philosopher. She was one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.[14][15][16]

Her works cover a broad range of topics, but she is best known for those dealing with the nature of power and evil, as well as politics, direct democracy, authority, and totalitarianism. She is also remembered for the controversy surrounding the trial of Adolf Eichmann, her attempt to explain how ordinary people become actors in totalitarian systems, which was considered by some an apologia, and for the phrase "the banality of evil." She is commemorated by institutions and journals devoted to her thinking, the Hannah Arendt Prize for political thinking, and on stamps, street names and schools, amongst other things.

Arendt was born to a Jewish family in Linden (now a district of Hanover, Germany) in 1906. When she was three, her family moved to the East Prussian capital of Königsberg for her father's health care. Paul Arendt had contracted syphilis in his youth, but was thought to be in remission when Arendt was born. He died when she was seven. Arendt was raised in a politically progressive, secular family, her mother being an ardent Social Democrat. After completing secondary education in Berlin, Arendt studied at the University of Marburg under Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a four-year affair.[17] She obtained her doctorate in philosophy at the University of Heidelberg in 1929. Her dissertation was entitled Love and Saint Augustine and her supervisor was the existentialist philosopher Karl Jaspers.

Hannah Arendt married Günther Stern in 1929, but soon began to encounter increasing antisemitism in 1930s Nazi Germany. In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler came to power, Arendt was arrested and briefly imprisoned by the Gestapo for performing illegal research into antisemitism. On release, she fled Germany, living in Czechoslovakia and Switzerland before settling in Paris. There she worked for Youth Aliyah, assisting young Jews to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine. She was stripped of her German citizenship in 1937. Divorcing Stern that year, she then married Heinrich Blücher in 1940. When Germany invaded France that year she was detained by the French as an alien. She escaped and made her way to the United States in 1941 via Portugal. She settled in New York, which remained her principal residence for the rest of her life. She became a writer and editor and worked for the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, becoming an American citizen in 1950. With the publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951, her reputation as a thinker and writer was established and a series of works followed. These included the books The Human Condition in 1958, as well as Eichmann in Jerusalem and On Revolution in 1963. She taught at many American universities, while declining tenure-track appointments. She died suddenly of a heart attack in 1975, at the age of 69, leaving her last work, The Life of the Mind, unfinished.

Early life and education (1906–1929)

Family

Hannah Arendt was born as Johanna Arendt[18][19] in 1906, in the Wilhelmine period. Her Jewish family in Germany were comfortable, educated and secular in Linden, Prussia (now a part of Hanover). They were merchants of Russian extraction from Königsberg.[lower-alpha 1] Her grandparents were members of the Reform Jewish community. Her paternal grandfather, Max Arendt, was a prominent businessman, local politician,[20] a leader of the Königsberg Jewish community and a member of the Central Organization for German Citizens of Jewish Faith (Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens). Like other members of the Centralverein he primarily saw himself as German, disapproving of Zionist activities including Kurt Blumenfeld, a frequent visitor and later one of Hannah's mentors. Of Max Arendt's children, Paul Arendt was an engineer and Henriette Arendt a policewoman and social worker.[21][22]

Hannah was the only child of Paul and Martha Arendt (née Cohn), who were married on 11 April 1902. She was named after her paternal grandmother.[23][24] The Cohns had originally come to Königsberg from nearby Russian territory (now Lithuania) in 1852, as refugees from antisemitism, and made their living as tea importers, J. N. Cohn & Company being the largest business in the city. The Arendts reached Germany from Russia a century earlier.[25][26] Hannah's extended family contained many more women, who shared the loss of husbands and children. Hannah's parents were more educated and politically more to the left than her grandparents. The young couple were Social Democrats,[18] rather than the German Democrats that most of their contemporaries supported. Paul Arendt was educated at the Albertina (University of Königsberg). Though he worked as an engineer, he prided himself on his love of Classics, with a large library that Hannah immersed herself in. Martha Cohn, a musician, had studied for three years in Paris.[22]

In the first four years of their marriage, the Arendts lived in Berlin, and were supporters of the socialist journal Socialist Monthly Bulletins (Sozialistische Monatshefte).[lower-alpha 2][27] At the time of Hannah's birth, Paul Arendt was employed by an electrical engineering firm in Linden, and they lived in a frame house on the market square (Marktplatz).[28] They moved back to Königsberg in 1909 because of Paul's deteriorating health.[7][29] He suffered from chronic syphilis and was institutionalized in the Königsberg psychiatric hospital in 1911. For years afterward, Hannah had to have annual WR tests for congenital syphilis.[30] He died on 30 October 1913, when Hannah was seven, leaving her mother to raise her.[23][31] They lived at Hannah's grandfather's house at Tiergartenstraße 6, a leafy residential street adjacent to the Königsberg Tiergarten, in the predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Hufen.[32] Although Hannah's parents were non-religious, they were happy to allow Max Arendt to take Hannah to the Reform synagogue. She also received religious instruction from the rabbi, Hermann Vogelstein, who would come to her school for that purpose.[lower-alpha 3] Her family moved in circles that included many intellectuals and professionals. It was a social circle of high standards and ideals. As she recalled it:[33]

My early intellectual formation occurred in an atmosphere where nobody paid much attention to moral questions; we were brought up under the assumption: Das Moralische versteht sich von selbst, moral conduct is a matter of course.

This time was a particularly favorable period for the Jewish community in Königsberg, an important center of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment).[34][35] Arendt's family was thoroughly assimilated ("Germanized")[36] and she later remembered: "With us from Germany, the word 'assimilation' received a 'deep' philosophical meaning. You can hardly realize how serious we were about it."[37] Despite these conditions, the Jewish population lacked full citizenship rights, and although antisemitism was not overt, it was not absent.[38] Arendt came to define her Jewish identity negatively after encountering overt antisemitism as an adult.[37] She came to greatly identify with Rahel Varnhagen, the Prussian socialite[31] who desperately wanted to assimilate into German culture, only to be rejected because she was born Jewish.[37] Arendt later said of Varnhagen that she was "my very closest woman friend, unfortunately dead a hundred years now."[37][lower-alpha 4]

In the last two years of the First World War, Hannah's mother organized social democratic discussion groups and became a follower of Rosa Luxemburg as socialist uprisings broke out across Germany.[27][40] Luxemburg's writings would later influence Hannah's political thinking. In 1920, Martha Cohn married Martin Beerwald, an ironmonger and widower of four years, and they moved to his home, two blocks away, at Busoldstrasse 6,[41][42] providing Hannah with improved social and financial security. Hannah was 14 at the time and acquired two older stepsisters, Clara and Eva.[41]

Education

Early education

Hannah Arendt's mother, who considered herself progressive, brought her daughter up on strict Goethean lines. Among other things this involved the reading of Goethe's complete works, summed up as Was aber ist deine Pflicht? Die Forderung des Tages (And just what is your duty? The demands of the day).[lower-alpha 5] Goethe, was then considered the essential mentor of Bildung (education), the conscious formation of mind, body and spirit. The key elements were considered to be self-discipline, constructive channeling of passion, renunciation and responsibility for others. Hannah's developmental progress (Entwicklung) was carefully documented by her mother in a book, she called Unser Kind (Our Child), measuring her against the benchmark of what was then considered normale Entwicklung ("normal development").[43]

Arendt attended kindergarten from 1910 where her precocity impressed her teachers and enrolled in the Szittnich School, Königsberg (Hufen-Oberlyzeum), on Bahnstraße in August 1913,[44] but her studies there were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, forcing the family to temporarily flee to Berlin on 23 August 1914, in the face of the advancing Russian army.[45] There they stayed with her mother's younger sister, Margarethe Fürst, and her three children, while Hannah attended a girl's Lyzeum school in Berlin-Charlottenburg. After ten weeks, when Königsberg appeared to be no longer threatened, the Arendts were able to return,[45] where they spent the remaining war years at her grandfather's house. Arendt's precocity continued, learning ancient Greek as a child,[46] writing poetry in her teenage years,[47] and starting both a Graecae (reading group for studying classical literature) and philosophy club at her school. She was fiercely independent in her schooling and a voracious reader,[lower-alpha 6] absorbing French and German literature and poetry (committing large amounts to heart) and philosophy. By the age of 14, she had read Kierkegaard, Jaspers' Psychologie der Weltanschauungen and Kant's Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason). Kant, whose home town was also Königsberg, was an important influence on her thinking, and it was Kant who had written about Königsberg that "such a town is the right place for gaining knowledge concerning men and the world even without travelling".[49][50]

Arendt attended the Königin-Luise-Schule for her secondary education, a girls' Gymnasium on Landhofmeisterstraße.[51] Most of her friends, while at school, were gifted children of Jewish professional families, generally older than she and went on to university education. Among them was Ernst Grumach, who introduced her to his girlfriend, Anne Mendelssohn,[lower-alpha 7] who would become a lifelong friend. When Anne moved away, Ernst became Arendt's first romantic relationship.[lower-alpha 8]

Higher education (1922–1929)

Berlin (1922–1924)

Arendt was expelled from the Luise-Schule in 1922, at the age of 15, for leading a boycott of a teacher who insulted her. Her mother sent her to Berlin to Social Democrat family friends. She lived in a student residence and audited courses at the University of Berlin (1922–1923), including classics and Christian theology under Romano Guardini. She successfully sat the entrance examination (Abitur) for the University of Marburg, where Ernst Grumach had studied under Martin Heidegger (appointed as a professor in 1922). Her mother had engaged a private tutor, and her aunt Frieda Arendt, a teacher, also helped, while Frieda's husband Ernst Aron provided financial tuition assistance.[54]

Marburg (1924–1926)

In Berlin, Guardini had introduced her to Kierkegaard, and she resolved to make theology her major field.[50] At Marburg (1924–1926) she studied classical languages, German literature, Protestant theology with Rudolf Bultmann and philosophy with Nicolai Hartmann and Heidegger.[55] She arrived in the fall in the middle of an intellectual revolution led by the young Heidegger, of whom she was in awe, describing him as "the hidden king [who] reigned in the realm of thinking".[56][57]

Heidegger had broken away from the intellectual movement started by Edmund Husserl, whose assistant he had been at University of Freiburg before coming to Marburg.[58] This was a period when Heidegger was preparing his lectures on Kant, which he would develop in the second part of his Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) in 1927 and Kant und das Problem der Metaphysik (1929). In his classes, he and his students struggled with the meaning of "Being" as they studied Aristotle's and Plato's Sophist concept of truth, to which Heidegger opposed the pre-Socratic term ἀλήθεια.[58] Many years later Arendt would describe these classes, how people came to Marburg to hear him, and how, above all he imparted the idea of Denken ("thinking") as activity, which she qualified as "passionate thinking".[59]

Arendt was restless, finding her studies neither emotionally or intellectually satisfying. She was ready for passion, finishing her poem Trost (Consolation, 1923) with the lines:[60]

Die Stunden verrinnen,

Die Tage vergehen,

Es bleibt ein Gewinnen

Das bloße Bestehen.

(The hours run down.

The days pass on.

One achievement remains:

merely being alive.)

Her encounter with Heidegger represented a dramatic departure from the past. He was handsome, a genius, romantic, and taught that thinking and "aliveness" were but one.[61] The 17-year-old Arendt then began a long romantic relationship with the 35-year-old Heidegger,[62] who was married with two young sons.[lower-alpha 9][58] Arendt later faced criticism for this because of Heidegger's support for the Nazi Party after his election as rector at Freiburg University in 1933. Nevertheless, he remained one of the most profound influences on her thinking,[63] and he would later relate that she had been the inspiration for his work on passionate thinking in those days. They agreed to keep the details of the relationship a secret although preserving their letters.[64] The relationship was unknown until Elisabeth Young-Bruehl's biography of Arendt appeared in 1982. At the time of publishing, Arendt and Heidegger were deceased but Heidegger's wife, Elfride, was still alive. The affair was not well known until 1995, when Elzbieta Ettinger gained access to the sealed correspondence[65] and published a controversial account that was used by Arendt's detractors to cast doubt on her integrity. That account,[lower-alpha 10] which caused a scandal, was subsequently refuted.[67][68][66]

At Marburg, Arendt lived at Lutherstraße 4.[69] Among her friends was Hans Jonas, her only Jewish classmate. Another fellow student of Heidegger's was Jonas' friend, the Jewish philosopher Günther Siegmund Stern, who would later become her first husband.[70] Stern had completed his doctoral dissertation with Edmund Husserl at Freiburg, and was now working on his Habilitation thesis with Heidegger, but Arendt, involved with Heidegger, took little notice of him at the time.[71]

Die Schatten (1925)

In the summer of 1925, while home at Königsberg, Arendt composed her sole autobiographical piece, Die Schatten (The Shadows), a "description of herself"[72][73] addressed to Heidegger.[lower-alpha 11][75] In this essay, full of anguish and Heideggerian language, she reveals her insecurities relating to her femininity and Jewishness, writing abstractly in the third person.[lower-alpha 12] She describes a state of "Fremdheit" (alienation), on the one hand an abrupt loss of youth and innocence, on the other an "Absonderlichkeit" (strangeness), the finding of the remarkable in the banal.[76] In her detailing of the pain of her childhood and longing for protection she shows her vulnerabilities and how her love for Heidegger had released her and once again filled her world with color and mystery. She refers to her relationship with Heidegger as "Eine starre Hingegebenheit an ein Einziges" ("an unbending devotion to a unique man").[37][77][78] This period of intense introspection was also one of the most productive of her poetic output,[79] such as In sich versunken (Lost in Self-Contemplation).[80]

Freiburg and Heidelberg (1926–1929)

After a year at Marburg, Arendt spent a semester at Freiburg, attending the lectures of Husserl.[9] In 1926 she moved to the University of Heidelberg, completing her dissertation in 1929 under Karl Jaspers.[40] Jaspers, a friend of Heidegger, was the other leading figure of the then new and revolutionary Existenzphilosophie.[46] Her thesis was entitled Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin: Versuch einer philosophischen Interpretation (On the concept of love in the thought of Saint Augustine: Attempt at a philosophical interpretation).[81] She remained a lifelong friend of Jaspers and his wife, Gertrud Mayer, developing a deep intellectual relationship with him.[82] At Heidelberg, her circle of friends included Hans Jonas, who had also moved from Marburg to study Augustine, working on his Augustin und das paulinische Freiheitsproblem. Ein philosophischer Beitrag zur Genesis der christlich-abendländischen Freiheitsidee (1930),[lower-alpha 13] and also a group of three young philosophers: Karl Frankenstein, Erich Neumann and Erwin Loewenson.[83] Other friends and students of Jaspers were the linguists Benno von Wiese and Hugo Friedrich (seen with Hannah, below), with whom she attended lectures by Friedrich Gundolf at Jaspers' suggestion and who kindled in her an interest in German Romanticism. She also became reacquainted, at a lecture, with Kurt Blumenfeld, who introduced her to Jewish politics. At Heidelberg, she lived in the old town (Altstadt) near the castle, at Schlossberg 16. The house was demolished in the 1960s, but the one remaining wall bears a plaque commemorating her time there (see image below).[84]

On completing her dissertation, Arendt turned to her Habilitationsschrift, initially on German Romanticism,[85] and thereafter an academic teaching career. However 1929 was also the year of the Depression and the end of the golden years (Goldene Zwanziger) of the Weimar Republic, which was to become increasingly unstable over its remaining four years. Arendt, as a Jew, had little if any chance of obtaining an academic appointment in Germany.[86] Nevertheless, she completed most of the work before she was forced to leave Germany.[87]

Career

Germany (1929–1933)

Berlin-Potsdam (1929)

.jpg.webp)

In 1929, Arendt met Günther Stern again, this time in Berlin at a New Year's masked ball,[88] and began a relationship with him.[lower-alpha 14][40][70] Within a month she had moved in with him in a one-room studio, shared with a dancing school in Berlin-Halensee. Then they moved to Merkurstraße 3, Nowawes,[89] in Potsdam[90] and were married there on 26 September.[lower-alpha 15][92] They had much in common and the marriage was welcomed by both sets of parents.[71] In the summer, Hannah Arendt successfully applied to the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft for a grant to support her Habilitation, which was supported by Heidegger and Jaspers among others, and in the meantime, with Günther's help was working on revisions to get her dissertation published.[93]

Wanderjahre (1929–1931)

After Arendt and Stern were married, they began two years of what Christian Dries refers to as the Wanderjahre (years of wandering) with the ultimately fruitless aim of having Stern accepted for an academic appointment.[94] They lived for a while in Drewitz,[95] a southern neighborhood of Potsdam, before moving to Heidelberg, where they lived with the Jaspers. After Heidelberg, where Stern completed the first draft of his Habilitation thesis, the two then moved to Frankfurt where Stern hoped to finish his writing. There, Arendt participated in the university's intellectual life, attending lectures by Karl Mannheim and Paul Tillich, among others.[96] The couple collaborated intellectually, writing an article together[97] on Rilke's Duino Elegies (1923)[98] and both reviewing Mannheim's Ideologie und Utopie (1929).[99] The latter was Arendt's sole contribution in sociology.[70][71][100] In both her treatment of Mannheim and Rilke, Arendt found love to be a transcendent principle "Because there is no true transcendence in this ordered world, one also cannot exceed the world, but only succeed to higher ranks".[lower-alpha 16] In Rilke she saw a latter day secular Augustine, describing the Elegies as the letzten literarischen Form religiösen Dokumentes (ultimate form of religious document). Later, she would discover the limitations of transcendent love in explaining the historical events that pushed her into political action.[101] Another theme from Rilke that she would develop was the despair of not being heard. Reflecting on Rilke's opening lines, which she placed as an epigram at the beginning of their essay

Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen?

(Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic orders?)

Arendt and Stern begin by stating:[102]

The paradoxical, ambiguous, and desperate situation from which standpoint the Duino Elegies may alone be understood has two characteristics: the absence of an echo and the knowledge of futility. The conscious renunciation of the demand to be heard, the despair at not being able to be heard, and finally the need to speak even without an answer–these are the real reasons for the darkness, asperity, and tension of the style in which poetry indicates its own possibilities and its will to form[lower-alpha 17]

Arendt also published an article on Augustine (354–430) in the Frankfurter Zeitung[103] to mark the 1500th anniversary of his death. She saw this article as forming a bridge between her treatment of Augustine in her dissertation and her subsequent work on Romanticism.[104][105] When it became evident Stern would not succeed in obtaining an appointment,[lower-alpha 18] the Sterns returned to Berlin in 1931.[31]

Return to Berlin (1931–1933)

In Berlin, where the couple initially lived in the predominantly Jewish area of Bayerisches Viertel (Bavarian Quarter or "Jewish Switzerland") in Schöneberg,[107][108] Stern obtained a position as a staff-writer for the cultural supplement of the Berliner Börsen-Courier, edited by Herbert Ihering, with the help of Bertold Brecht. There he started writing using the pen name Günther Anders, i.e. "Günther Other".[lower-alpha 19][70] Arendt assisted Günther with his work, but the shadow of Heidegger hung over their relationship. While Günther was working on his Habilitationsschrift, Arendt had abandoned the original subject of German Romanticism for her thesis in 1930, and turned instead to Rahel Varnhagen and the question of assimilation.[85][110] Anne Mendelssohn had accidentally acquired a copy of Varnhagen's correspondence and excitedly introduced her to Arendt, donating her collection to her. A little later, Arendt's own work on Romanticism led her to a study of Jewish salons and eventually to those of Varnhagen. In Rahel, she found qualities she felt reflected her own, particularly those of sensibility and vulnerability.[111] Rahel, like Hannah, found her destiny in her Jewishness. Hannah Arendt would come to call Rahel Varnhagen's discovery of living with her destiny as being a "conscious pariah".[112] This was a personal trait that Arendt had recognized in herself, although she did not embrace the term until later.[113]

Back in Berlin, Arendt found herself becoming more involved in politics and started studying political theory, and reading Marx and Trotsky, while developing contacts at the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik.[114] Despite the political leanings of her mother and husband she never saw herself as a political leftist, justifying her activism as being through her Jewishness.[115] Her increasing interest in Jewish politics and her examination of assimilation in her study of Varnhagen led her to publish her first article on Judaism, Aufklärung und Judenfrage ("The Enlightenment and the Jewish Question", 1932).[116][117] Blumenfeld had introduced her to the "Jewish question", which would be his lifelong concern.[118] Meanwhile, her views on German Romanticism were evolving. She wrote a review of Hans Weil's Die Entstehung des deutschen Bildungsprinzips (The Origin of German Educational Principle, 1930),[119] which dealt with the emergence of Bildungselite (educational elite) in the time of Rahel Varnhagen.[120] At the same time she began to be occupied by Max Weber's description of the status of Jewish people within a state as Pariavolk (pariah people) in his Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (1922),[121][122] while borrowing Bernard Lazare's term paria conscient (conscious pariah)[123] with which she identified.[lower-alpha 20][124][125][126] In both these articles she advanced the views of Johann Herder.[117] Another interest of hers at the time was the status of women, resulting in her 1932 review[127] of Alice Rühle-Gerstel's book Das Frauenproblem in der Gegenwart. Eine psychologische Bilanz (Contemporary Women's Issues: A psychological balance sheet).[128] Although not a supporter of the women's movement, the review was sympathetic. At least in terms of the status of women at that time, she was skeptical of the movement's ability to achieve political change.[129] She was also critical of the movement, because it was a women's movement, rather than contributing with men to a political movement, and abstract rather than striving for concrete goals. In this manner she echoed Rosa Luxemburg. Like Luxemburg, she would later criticize Jewish movements for the same reason. Arendt consistently prioritized political over social questions.[130]

By 1932, faced with a deteriorating political situation, Arendt was deeply troubled by reports that Heidegger was speaking at National Socialist meetings. She wrote, asking him to deny that he was attracted to National Socialism. Heidegger replied that he did not seek to deny the rumors (which were true), and merely assured her that his feelings for her were unchanged.[37] As a Jew in Nazi Germany, Arendt was prevented from making a living and discriminated against and confided to Anne Mendelssohn that emigration was probably inevitable. Jaspers had tried to persuade her to consider herself as a German first, a position she distanced herself from, pointing out that she was a Jew and that "Für mich ist Deutschland die Muttersprache, die Philosophie und die Dichtung" (For me, Germany is the mother tongue, philosophy and poetry), rather than her identity. This position puzzled Jaspers, replying "It is strange to me that as a Jew you want to be different from the Germans".[131]

By 1933, life for the Jewish population in Germany was becoming precarious. Adolf Hitler became Reichskanzler (Chancellor) in January, and the Reichstag was burned down (Reichstagsbrand) the following month. This led to the suspension of civil liberties, with attacks on the left, and, in particular, members of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (German Communist Party: KPD). Stern, who had communist associations, fled to Paris, but Arendt stayed on to become an activist. Knowing her time was limited, she used the apartment at Opitzstraße 6 in Berlin-Steglitz that she had occupied with Stern since 1932 as an underground railway way-station for fugitives. Her rescue operation there is now recognized with a plaque on the wall.[132][133]

_Hannah_Arendt.JPG.webp)

Arendt had already positioned herself as a critic of the rising Nazi Party in 1932 by publishing "Adam-Müller-Renaissance?"[134] a critique of the appropriation of the life of Adam Müller to support right wing ideology. The beginnings of anti-Jewish laws and boycott came in the spring of 1933. Confronted with systemic antisemitism, Arendt adopted the motiv "If one is attacked as a Jew one must defend oneself as a Jew. Not as a German, not as a world citizen, not as an upholder of the Rights of Man."[46][135] This was Arendt's introduction of the concept of Jew as Pariah that would occupy her for the rest of her life in her Jewish writings.[136] She took a public position by publishing part of her largely completed biography of Rahel Varnhagen as "Originale Assimilation: Ein Nachwort zu Rahel Varnhagen 100 Todestag" ("Original Assimilation: An Epilogue to the One Hundredth Anniversary of Rahel Varnhagen's Death") in the Kölnische Zeitung on 7 March 1933 and a little later also in Jüdische Rundschau.[lower-alpha 21][86] In the article she argues that the age of assimilation that began with Varnhagen's generation had come to an end with an official state policy of antisemitism. She opened with the declaration:[138]

Today in Germany it seems Jewish assimilation must declare its bankruptcy. The general social antisemitism and its official legitimation affects in the first instance assimilated Jews, who can no longer protect themselves through baptism or by emphasizing their differences from Eastern Judaism.[lower-alpha 22]

As a Jew, Arendt was anxious to inform the world of what was happening to her people in 1930–1933.[46] She surrounded herself with Zionist activists, including Kurt Blumenfeld, Martin Buber and Salman Schocken, and started to research antisemitism. Arendt had access to the Prussian State Library for her work on Varnhagen. Blumenfeld's Zionistische Vereinigung für Deutschland (Zionist Federation of Germany) persuaded her to use this access to obtain evidence of the extent of antisemitism, for a planned speech to the Zionist Congress in Prague. This research was illegal at the time.[140] Her actions led to her being denounced by a librarian for anti-state propaganda, resulting in the arrest of both Arendt and her mother by the Gestapo. They served eight days in prison but her notebooks were in code and could not be deciphered, and she was released by a young, sympathetic arresting officer to await trial.[31][55][141]

Exile: France (1933–1941)

Paris (1933–1940)

On release, realizing the danger she was now in, Arendt and her mother fled Germany[31] following the established escape route over the Ore Mountains by night into Czechoslovakia and on to Prague and then by train to Geneva. In Geneva, she made a conscious decision to commit herself to "the Jewish cause". She obtained work with a friend of her mother's at the League of Nations' Jewish Agency for Palestine, distributing visas and writing speeches.[142]

From Geneva the Arendts traveled to Paris in the autumn, where she was reunited with Stern, joining a stream of refugees.[143] While Arendt had left Germany without papers, her mother had travel documents and returned to Königsberg and her husband.[142] In Paris, she befriended Stern's cousin, the Marxist literary critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin and also the Jewish French philosopher Raymond Aron.[143]

Arendt was now an émigrée, an exile, stateless, without papers, and had turned her back on the Germany and Germans of the Nazizeit.[46] Her legal status was precarious and she was coping with a foreign language and culture, all of which took its toll on her mentally and physically.[144] In 1934 she started working for the Zionist-funded outreach program Agriculture et Artisanat,[145] giving lectures, and organizing clothing, documents, medications and education for Jewish youth seeking to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine, mainly as agricultural workers. Initially she was employed as a secretary, and then office manager. To improve her skills she studied French, Hebrew and Yiddish. In this way she was able to support herself and her husband.[146] When the organization closed in 1935, her work for Blumenfeld and the Zionists in Germany brought her into contact with the wealthy philanthropist Baroness Germaine Alice de Rothschild (born Halphen, 1884–1975),[147] wife of Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild, becoming her assistant. In this position she oversaw the baroness' contributions to Jewish charities through the Paris Consistoire, although she had little time for the family as a whole.[142][lower-alpha 23]

Later in 1935, Arendt joined Youth Aliyah (Youth immigration),[lower-alpha 24] an organization similar to Agriculture et Artisanat that was founded in Berlin on the day Hitler seized power. It was affiliated with Hadassah,[149][150] which later saved many from the Holocaust,[151][152][31] and there Arendt eventually became Secretary-General (1935–1939).[19][143] Her work with Youth Aliyah also involved finding food, clothing, social workers and lawyers, but above all, fund raising.[55] She made her first visit to British Mandate of Palestine in 1935, accompanying one of these groups and meeting with her cousin Ernst Fürst there.[lower-alpha 25][144] With the Nazi annexation of Austria and invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938, Paris was flooded with refugees, and she became the special agent for the rescue of the children from those countries.[19] In 1938, Arendt completed her biography of Rahel Varnhagen,[39][154][155] although this was not published until 1957.[31][156] In April 1939, following the devastating Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, Martha Beerwald realized her daughter would not return and made the decision to leave her husband and join Arendt in Paris. One stepdaughter had died and the other had moved to England, Martin Beerwald would not leave and she no longer had any close ties to Königsberg.[157]

Heinrich Blücher

In 1936, Arendt met the self-educated Berlin poet and Marxist philosopher Heinrich Blücher in Paris.[31][158] Blücher had been a Spartacist and then a founding member of the KPD, but had been expelled due to his work in the Versöhnler (Conciliator faction).[118][159][160] Although Arendt had rejoined Stern in 1933, their marriage existed in name only, with their having separated in Berlin.[lower-alpha 26] She fulfilled her social obligations and used the name Hannah Stern, but the relationship effectively ended when Stern, perhaps recognizing the danger better than she, emigrated to America with his parents in 1936.[144] In 1937, Arendt was stripped of her German citizenship and she and Stern divorced. She had begun seeing more of Blücher, and eventually they began living together. It was Blücher's long political activism that began to move Arendt's thinking towards political action.[118] Arendt and Blücher married on 16 January 1940, shortly after their divorces were finalized.[161]

Internment and escape (1940–1941)

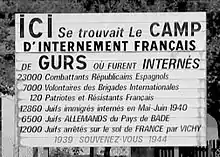

On 5 May 1940, in anticipation of the German invasion of France and the Low Countries that month, the military governor of Paris issued a proclamation ordering all "enemy aliens" between 17 and 55 who had come from Germany (predominantly Jews) to report separately for internment. The women were gathered together in the Vélodrome d'Hiver on 15 May, so Hannah Arendt's mother, being over 55, was allowed to stay in Paris. Arendt described the process of making refugees as "the new type of human being created by contemporary history ... put into concentration camps by their foes and into internment camps by their friends".[161][162] The men, including Blücher, were sent to Camp Vernet in southern France, close to the Spanish border. Arendt and the other women were sent to Camp Gurs, to the west of Gurs, a week later. The camp had earlier been set up to accommodate refugees from Spain. On 22 June, France capitulated and signed the Compiègne armistice, dividing the country. Gurs was in the southern Vichy controlled section. Arendt describes how, "in the resulting chaos we succeeded in getting hold of liberation papers with which we were able to leave the camp",[163] which she did with about 200 of the 7,000 women held there, about four weeks later.[164] There was no Résistance then, but she managed to walk and hitchhike north to Montauban,[lower-alpha 27] near Toulouse where she knew she would find help.[162][165]

Montauban had become an unofficial capital for former detainees,[lower-alpha 28] and Arendt's friend Lotta Sempell Klembort was staying there. Blücher's camp had been evacuated in the wake of the German advance, and he managed to escape from a forced march, making his way to Montauban, where the two of them led a fugitive life. Soon they were joined by Anne Mendelssohn and Arendt's mother. Escape from France was extremely difficult without official papers; their friend Walter Benjamin had taken his own life after being apprehended trying to escape to Spain. One of the best known illegal routes operated out of Marseilles, where Varian Fry, an American journalist, worked to raise funds, forge papers and bribe officials with Hiram Bingham, the American vice-consul there.

Fry and Bingham secured exit papers and American visas for thousands, and with help from Günther Stern, Arendt, her husband, and her mother managed to secure the requisite permits to travel by train in January 1941 through Spain to Lisbon, Portugal, where they rented a flat at Rua da Sociedade Farmacêutica, 6b.[lower-alpha 29][169] They eventually secured passage to New York in May on the Companhia Colonial de Navegação's S/S Guiné II.[170] A few months later, Fry's operations were shut down and the borders sealed.[171][172]

New York (1941–1975)

World War II (1941–1945)

Upon arriving in New York City on 22 May 1941 with very little, Hannah's family received assistance from the Zionist Organization of America and the local German immigrant population, including Paul Tillich and neighbors from Königsberg. They rented rooms at 317 West 95th Street and Martha Arendt joined them there in June. There was an urgent need to acquire English, and it was decided that Hannah Arendt should spend two months with an American family in Winchester, Massachusetts, through Self-Help for Refugees, in July.[173] She found the experience difficult but formulated her early appraisal of American life, Der Grundwiderspruch des Landes ist politische Freiheit bei gesellschaftlicher Knechtschaft (The fundamental contradiction of the country is political freedom coupled with social slavery).[lower-alpha 30][174]

On returning to New York, Arendt was anxious to resume writing and became active in the German-Jewish community, publishing her first article, "From the Dreyfus Affair to France Today" (in translation from her German) in July 1941.[lower-alpha 31][176] While she was working on this article, she was looking for employment and in November 1941 was hired by the New York German-language Jewish newspaper Aufbau and from 1941 to 1945, she wrote a political column for it, covering antisemitism, refugees and the need for a Jewish army. She also contributed to the Menorah Journal, a Jewish-American magazine,[177] and other German émigré publications.[31]

Arendt's first full-time salaried job came in 1944, when she became the director of research and executive director for the newly emerging Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, a project of the Conference on Jewish Relations.[lower-alpha 32] She was recruited "because of her great interest in the Commission's activities, her previous experience as an administrator, and her connections with Germany". There she compiled lists of Jewish cultural assets in Germany and Nazi occupied Europe, to aid in their recovery after the war.[180] Together with her husband, she lived at 370 Riverside Drive in New York City and at Kingston, New York, where Blücher taught at nearby Bard College for many years.[31][181]

Post-war (1945–1975)

.jpg.webp)

In July 1946, Arendt left her position at the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction to become an editor at Schocken Books, which later published some of her works.[31][182] In 1948, she became engaged with the campaign of Judah Magnes for a solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[118] She famously opposed the establishment of a Jewish nation state in Palestine and initially also opposed the establishment of a binational Arab-Jewish state. Instead, she advocated for the inclusion of Palestine into a multi-ethnic federation. Only in 1948 in an effort to forestall partition did she support a binational one-state solution.[183] She returned to the Commission in August 1949. In her capacity as executive secretary, she traveled to Europe, where she worked in Germany, Britain and France (December 1949 to March 1950) to negotiate the return of archival material from German institutions, an experience she found frustrating, but provided regular field reports.[184] In January 1952, she became secretary to the Board, although the work of the organization was winding down[lower-alpha 33] and she was simultaneously pursuing her own intellectual activities; she retained this position until her death.[lower-alpha 34][180][185][186] Arendt's work on cultural restitution provided further material for her study of totalitarianism.[187]

In the 1950s Arendt wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951),[188] The Human Condition (1958)[189] followed by On Revolution (1963).[31][190] Arendt began corresponding with the American author Mary McCarthy, six years her junior, in 1950 and they soon became lifelong friends.[191][192] In 1950, Arendt also became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[193] The same year, she started seeing Martin Heidegger again, and had what the American writer Adam Kirsch called a "quasi-romance", lasting for two years, with the man who had previously been her mentor, teacher, and lover.[37] During this time, Arendt defended him against critics who noted his enthusiastic membership in the Nazi Party. She portrayed Heidegger as a naïve man swept up by forces beyond his control, and pointed out that Heidegger's philosophy had nothing to do with National Socialism.[37] She suspected that loyal followers of Horkheimer and Adorno in Frankfurt were plotting against Heidegger. For Adorno she had a real aversion: "Half a Jew and one of the most repugnant men I know".[194][82] According to Arendt, the Frankfurt School was willing, and quite capable of doing so, to destroy Heidegger: "For years they have branded anti-Semitism on anyone in Germany who opposes them, or have threatened to raise such an accusation".[194][82]

In 1961 she traveled to Jerusalem to report on Eichmann's trial for The New Yorker. This report strongly influenced her popular recognition, and raised much controversy (see below). Her work was recognized by many awards, including the Danish Sonning Prize in 1975 for Contributions to European Civilization.[46][195]

A few years later she spoke in New York City on the legitimacy of violence as a political act: "Generally speaking, violence always rises out of impotence. It is the hope of those who have no power to find a substitute for it and this hope, I think, is in vain. Violence can destroy power, but it can never replace it."[196]

Teaching

.jpg.webp)

Arendt taught at many institutions of higher learning from 1951 onwards, but, preserving her independence, consistently refused tenure-track positions. She was a visiting scholar at the University of Notre Dame, University of California, Berkeley, Princeton University (where she was the first woman to be appointed a full professor in 1959) and Northwestern University. She also taught at the University of Chicago from 1963 to 1967, where she was a member of the Committee on Social Thought, [181][197] Yale University, where she was a fellow and the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University (1961–62, 1962–63). From 1967 she was a professor at the New School for Social research in Manhattan, New York City.[31][198]

She was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1962[199] and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1964.[200] In 1974, Arendt was instrumental in the creation of Structured Liberal Education (SLE) at Stanford University. She wrote a letter to the president of Stanford to persuade the university to enact Stanford history professor Mark Mancall's vision of a residentially-based humanities program.[181] At the time of her death, she was University Professor of Political Philosophy at The New School.[181]

Relationships

.jpg.webp)

In addition to her affair with Heidegger, and her two marriages, Arendt had close friendships. Since her death, her correspondence with many of them has been published, revealing much information about her thinking. To her friends she was both loyal and generous, dedicating several of her works to them.[201] Freundschaft (friendship) she described as being one of "tätigen Modi des Lebendigseins" (the active modes of being alive),[202] and, to her, friendship was central both to her life and to the concept of politics.[201][203] Hans Jonas described her as having a "genius for friendship", and, in her own words, "der Eros der Freundschaft" (love of friendship).[201][204]

Her philosophy-based friendships were male and European, while her later American friendships were more diverse, literary, and political. Although she became an American citizen in 1950, her cultural roots remained European, and her language remained her German "Muttersprache" (mother tongue).[205] She surrounded herself with German-speaking émigrés, sometimes referred to as "The Tribe". To her, wirkliche Menschen (real people) were "pariahs", not in the sense of outcasts, but in the sense of outsiders, unassimilated, with the virtue of "social nonconformism ... the sine qua non of intellectual achievement", a sentiment she shared with Jaspers.[206]

Arendt always had a beste Freundin (best friend [female]). In her teens she had formed a lifelong relationship with her Jugendfreundin, Anne Mendelssohn Weil ("Ännchen"). After her emigration to America, Hilde Fränkel, Paul Tillich's secretary and mistress, filled that role until the latter's death in 1950. After the war, Arendt was able to return to Germany and renew her relationship with Weil, who made several visits to New York, especially after Blücher's death in 1970. Their last meeting was in Tegna, Switzerland in 1975, shortly before Arendt's death.[207] With Fränkel's death, Mary McCarthy became Arendt's closest friend and confidante.[53][208][209]

Final illness and death

Heinrich Blücher had survived a cerebral aneurysm in 1961 and remained unwell after 1963, sustaining a series of heart attacks. On 31 October 1970 he died of a massive heart attack. A devastated Arendt had previously told Mary McCarthy, "Life without him would be unthinkable".[210] Arendt was also a heavy smoker and was frequently depicted with a cigarette in her hand. She sustained a near fatal heart attack while lecturing in Scotland in May 1974, and although she recovered, she remained in poor health afterwards, and continued to smoke.[211] On the evening of 4 December 1975, shortly after her 69th birthday, she had a further heart attack in her apartment while entertaining friends, and was pronounced dead at the scene.[212][213] Her ashes were buried alongside those of Blücher at Bard College, in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York in May 1976.[181][214]

After Arendt's death the title page of the final part of The Life of the Mind ("Judging") was found in her typewriter, which she had just started, consisting of the title and two epigraphs. This has subsequently been reproduced in the edited version of her Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy.(see image).[215]

Work

Arendt wrote works on intellectual history as a political theorist, using events and actions to develop insights into contemporary totalitarian movements and the threat to human freedom presented by scientific abstraction and bourgeois morality. Intellectually, she was an independent thinker, a loner not a "joiner," separating herself from schools of thought or ideology.[216] In addition to her major texts she published anthologies, including Between Past and Future (1961),[217] Men in Dark Times (1968)[218] and Crises of the Republic (1972).[219] She also contributed to many publications, including The New York Review of Books, Commonweal, Dissent and The New Yorker.[31] She is perhaps best known for her accounts of Adolf Eichmann and his trial,[220] because of the intense controversy that it generated.[221]

Political theory and philosophical system

While Arendt never developed a systematic political theory and her writing does not easily lend itself to categorization, the tradition of thought most closely identified with Arendt is that of civic republicanism, from Aristotle to Tocqueville. Her political concept is centered around active citizenship that emphasizes civic engagement and collective deliberation.[9] She believed that no matter how bad, government could never succeed in extinguishing human freedom, despite holding that modern societies frequently retreat from democratic freedom with its inherent disorder for the relative comfort of administrative bureaucracy. Some have claimed her political legacy is her strong defence of freedom in the face of an increasingly less than free world.[31] She does not adhere to a single systematic philosophy, but rather spans a range of subjects covering totalitarianism, revolution, the nature of freedom and the faculties of thought and judgment.[7]

While she is best known for her work on "dark times",[lower-alpha 35] the nature of totalitarianism and evil, she imbued this with a spark of hope and confidence in the nature of mankind:[216]

That even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination might well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and their works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given to them. Men in Dark Times (1968)[224]

Love and Saint Augustine (1929)

Arendt's doctoral thesis, Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin. Versuch einer philosophischen Interpretation[81] (Love and Saint Augustine. Towards a philosophical interpretation), was published in 1929 and attracted critical interest, although an English translation did not appear until 1996.[225] In this work she combined approaches of both Heidegger and Jaspers. Arendt's interpretation of love in the work of Augustine deals with three concepts, love as craving or desire (Amor qua appetitus), love in the relationship between man (creatura) and creator (Creator – Creatura), and neighborly love (Dilectio proximi). Love as craving anticipates the future, while love for the Creator deals with the remembered past. Of the three, dilectio proximi or caritas[lower-alpha 36] is perceived as the most fundamental, to which the first two are oriented, which she treats as vita socialis (social life) – the second of the Great Commandments (or Golden Rule) "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself" uniting and transcending the former.[lower-alpha 37][90] Augustine's influence (and Jaspers' views on his work) persisted in Arendt's writings for the rest of her life.[227]

Amor mundi – warum ist es so schwer, die Welt zu lieben?

Love of the world – why is it so difficult to love the world?

—Denktagebuch I: 522[228]

Some of the leitmotifs of her canon were apparent, introducing the concept of Natalität (Natality) as a key condition of human existence and its role in the development of the individual,[225][229][230] developing this further in The Human Condition (1958).[189][231] She explained that the construct of natality was implied in her discussion of new beginnings and man's elation to the Creator as nova creatura.[232][233] The centrality of the theme of birth and renewal is apparent in the constant reference to Augustinian thought, and specifically the innovative nature of birth, from this, her first work, to her last, The Life of the Mind.[234]

Love is another connecting theme. In addition to the Augustinian loves expostulated in her dissertation, the phrase amor mundi (love of the world) is one often associated with Arendt and both permeates her work and was an absorbing passion throughout her work.[235][236] She took the phrase from Augustine's homily on the first epistle of St John, "If love of the world dwell in us".[237] Amor mundi was her original title for The Human Condition (1958),[lower-alpha 38][239] the subtitle of Elisabeth Young-Bruehl's biography (1982),[69] the title of a collection of writing on faith in her work[240] and is the newsletter of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.[241]

The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

Arendt's first major book, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951),[188] examined the roots of Stalinism and Nazism, structured as three essays, "Antisemitism", "Imperialism" and "Totalitarianism". Arendt argues that totalitarianism was a "novel form of government," that "differs essentially from other forms of political oppression known to us such as despotism, tyranny and dictatorship"[242] in that it applied terror to subjugate mass populations rather than just political adversaries.[243][244] Arendt also maintained that Jewry was not the operative factor in the Holocaust, but merely a convenient proxy because Nazism was about terror and consistency, not merely eradicating Jews.[244][245] Arendt explained the tyranny using Kant's phrase "radical evil",[246] by which their victims became "superfluous people".[247][248] In later editions she enlarged the text[249] to include her work on "Ideology and Terror: A novel form of government"[243] and the Hungarian Revolution, but then published the latter separately.[250][251][252]

Criticism of Origins has often focused on its portrayal of the two movements, Hitlerism and Stalinism, as equally tyrannical.[253]

Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess (1957)

Arendt's Habilitationsschrift on Rahel Varnhagen was completed while she was living in exile in Paris in 1938, but not published till 1957, in the United Kingdom by East and West Library, part of the Leo Baeck Institute.[254] This biography of a 19th-century Jewish socialite, formed an important step in her analysis of Jewish history and the subjects of assimilation and emancipation, and introduced her treatment of the Jewish diaspora as either pariah or parvenu. In addition it represents an early version of her concept of history.[255][256] The book is dedicated to Anne Mendelssohn, who first drew her attention to Varnhagen.[85][257][258] Arendt's relation to Varnhagen permeates her subsequent work. Her account of Varnhagen's life was perceived during a time of the destruction of German-Jewish culture. It partially reflects Arendt's own view of herself as a German-Jewish woman driven out of her own culture into a stateless existence,[255] leading to the description "biography as autobiography".[256][259][260]

The Human Condition (1958)

In what is arguably her most influential work, The Human Condition (1958),[189] Arendt differentiates political and social concepts, labor and work, and various forms of actions; she then explores the implications of those distinctions. Her theory of political action, corresponding to the existence of a public realm, is extensively developed in this work. Arendt argues that, while human life always evolves within societies, the social part of human nature, political life, has been intentionally realized in only a few societies as a space for individuals to achieve freedom. Conceptual categories, which attempt to bridge the gap between ontological and sociological structures, are sharply delineated. While Arendt relegates labor and work to the realm of the social, she favors the human condition of action as that which is both existential and aesthetic.[9] Of human actions, Arendt identifies two that she considers essential. These are forgiving past wrong (or unfixing the fixed past) and promising future benefit (or fixing the unfixed future).[261]

Arendt had first introduced the concept of "natality" in her Love and Saint Augustine (1929)[81] and in The Human Condition starts to develop this further. In this, she departs from Heidegger's emphasis on mortality. Arendt's positive message is one of the "miracle of beginning", the continual arrival of the new to create action, that is to alter the state of affairs brought about by previous actions.[262] "Men", she wrote "though they must die, are not born in order to die but in order to begin". She defined her use of "natality" as:[263]

The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, "natural" ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted. It is, in other words, the birth of new men and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born.

Natality would go on to become a central concept of her political theory, and also what Karin Fry considers its most optimistic one.[231]

Between Past and Future (1954...1968)

Between Past and Future is an anthology of eight essays written between 1954 and 1968, dealing with a variety of different but connected philosophical subjects. These essays share the central idea that humans live between the past and the uncertain future. Man must permanently think to exist, but must learn thinking. Humans have resorted to tradition, but are abandoning respect for this tradition and culture. Arendt tries to find solutions to help humans think again, since modern philosophy has not succeeded in helping humans to live correctly.[217]

On Revolution (1963)

Arendt's book On Revolution[264] presents a comparison of two of the main revolutions of the 18th century, the American and French Revolutions. She goes against a common impression of both Marxist and leftist views when she argues that France, while well-studied and often emulated, was a disaster and that the largely ignored American Revolution was a success. The turning point in the French Revolution occurred when the leaders rejected their goals of freedom in order to focus on compassion for the masses. In the United States, the founders never betray the goal of Constitutio Libertatis. Arendt believes the revolutionary spirit of those men had been lost, however, and advocates a "council system" as an appropriate institution to regain that spirit.[265]

Men in Dark Times (1968)

The anthology of essays Men in Dark Times presents intellectual biographies of some creative and moral figures of the 20th century, such as Walter Benjamin, Karl Jaspers, Rosa Luxemburg, Hermann Broch, Pope John XXIII, and Isak Dinesen.[218]

Crises of the Republic (1972)

Crises of the Republic[219] was the third of Arendt's anthologies, consisting of four essays. These related essays deal with contemporary American politics and the crises it faced in the 1960s and 1970s. "Lying in Politics" looks for an explanation behind the administration's deception regarding the Vietnam War, as revealed in the Pentagon Papers. "Civil Disobedience" examines the opposition movements, while the final "Thoughts on Politics and Revolution" is a commentary, in the form of an interview on the third essay, "On Violence".[219][266] In "On Violence" Arendt substantiates that violence presupposes power which she understands as a property of groups. Thus, she breaks with the predominant conception of power as derived from violence.

The Life of the Mind (1978)

Arendt's last major work, The Life of the Mind[267] remained incomplete at the time of her death in 1975, but marked a return to moral philosophy. The outline of the book was based on her graduate level political philosophy class, Philosophy of the Mind, and her Gifford Lectures in Scotland.[268] She conceived of the work as a trilogy based on the mental activities of thinking, willing, and judging. Her most recent work had focused on the first two, but went beyond this in terms of vita activa. Her discussion of thinking was based on Socrates and his notion of thinking as a solitary dialogue between oneself, leading her to novel concepts of conscience.[269]

Arendt died suddenly five days after completing the second part, with the first page of Judging still in her typewriter, and McCarthy then edited the first two parts and provided some indication of the direction of the third.[270][271] Arendt's exact intentions for the third part are unknown but she left several manuscripts (such as Thinking and Moral Considerations, Some Questions on Moral Philosophy and Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy) relating to her thoughts on the mental faculty of Judging. These have since been published separately.[272][273]

Collected works

After Arendt's death in 1975, her essays and notes have continued to be collected, edited and published posthumously by friends and colleagues, mainly under the editorship of Jerome Kohn, including those that give some insight into the unfinished third part of The Life of the Mind.[182] Some dealt with her Jewish identity. The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age (1978),[274] is a collection of 15 essays and letters from the period 1943–1966 on the situation of Jews in modern times, to try and throw some light on her views on the Jewish world, following the backlash to Eichmann, but proved to be equally polarizing.[275][276] A further collection of her writings on being Jewish was published as The Jewish Writings (2007).[277][278] Her work on moral philosophy appeared as Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy (1982) and Responsibility and Judgment (2003), and her literary works as Reflections on Literature and Culture (2007).[182]

Other work includes the collection of forty, largely fugitive,[lower-alpha 39] essays, addresses, and reviews covering the period 1930–1954, entitled Essays in Understanding 1930–1954: Formation, Exile, and Totalitarianism (1994).[279] These presaged her monumental The Origins of Totalitarianism,[188] in particular On the Nature of Totalitarianism (1953) and The Concern with Politics in Contemporary European Philosophical Thought (1954).[280] However these attracted little attention. However after a new version of Origins of Totalitarianism appeared in 2004 followed by The Promise of Politics in 2005 there appeared a new interest in Arendtiana. This led to a second series of her remaining essays, Thinking Without a Banister: Essays in Understanding, 1953–1975, published in 2018.[281] Her notebooks which form a series of memoirs, were published as Denktagebuch in 2002.[282][283][284]

Correspondence

Some further insight into her thinking is provided in the continuing posthumous publication of her correspondence with many of the important figures in her life, including Karl Jaspers (1992),[82] Mary McCarthy (1995),[192] Heinrich Blücher (1996),[285] Martin Heidegger (2004),[lower-alpha 40][74] Alfred Kazin (2005),[286] Walter Benjamin (2006),[287] Gershom Scholem (2011)[288] and Günther Stern (2016).[289] Other correspondences that have been published include those with women friends such as Hilde Fränkel and Anne Mendelsohn Weil (see Relationships).[290][287]

Arendt and the Eichmann trial (1961–1963)

In 1960, on hearing of Adolf Eichmann's capture and plans for his trial, Hannah Arendt contacted The New Yorker and offered to travel to Israel to cover it when it opened on 11 April 1961.[291] Arendt was anxious to test her theories, developed in The Origins of Totalitarianism, and see how justice would be administered to the sort of man she had written about. Also she had witnessed "little of the Nazi regime directly"[lower-alpha 41][292] and this was an opportunity to witness an agent of totalitarianism first hand.[248] The offer was accepted and she attended six weeks of the five-month trial with her young Israeli cousin, Edna Brocke.[291] On arrival she was treated as a celebrity, meeting with the trial chief judge, Moshe Landau, and the foreign minister, Golda Meir.[293] In her subsequent 1963 report,[294] based on her observations and transcripts,[291] and which evolved into the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,[220] Arendt coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe the Eichmann phenomenon. She, like others,[295] was struck by his very ordinariness and the demeanor he exhibited of a small, slightly balding, bland bureaucrat, in contrast to the horrific crimes he stood accused of.[296] He was, she wrote, "terribly and terrifyingly normal."[297] She examined the question of whether evil is radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness, a tendency of ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without a critical evaluation of the consequences of their actions. Arendt's argument was that Eichmann was not a monster, contrasting the immensity of his actions with the very ordinariness of the man himself. Eichmann, she stated, not only called himself a Zionist, having initially opposed the Jewish persecution, but also expected his captors to understand him. She pointed out that his actions were not driven by malice, but rather blind dedication to the regime and his need to belong, to be a "joiner."

On this, Arendt would later state "Going along with the rest and wanting to say 'we' were quite enough to make the greatest of all crimes possible".[lower-alpha 42][298] What Arendt observed during the trial was a bourgeois sales clerk who found a meaningful role for himself and a sense of importance in the Nazi movement. She noted that his addiction to clichés and use of bureaucratic morality clouded his ability to question his actions, "to think". This led her to set out her most debated dictum: "the lesson that this long course in human wickedness had taught us – the lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil."[31][294] By stating that Eichmann did not think, she did not imply lack of conscious awareness of his actions, but by "thinking" she implied reflective rationality, that was lacking.

Arendt was critical of the way the trial was conducted by the Israelis as a "show trial" with ulterior motives other than simply trying evidence and administering justice.[299][293] Arendt was also critical of the way Israel depicted Eichmann's crimes as crimes against a nation state, rather than against humanity itself.[300] She objected to the idea that a strong Israel was necessary to protect world Jewry being again placed where "they'll let themselves be slaughtered like sheep," recalling the biblical phrase.[lower-alpha 43][301] She portrayed the prosecutor, Attorney General Gideon Hausner, as employing hyperbolic rhetoric in the pursuit of Prime Minister Ben-Gurion's political agenda.[302] Arendt, who believed she could maintain her focus on moral principles in the face of outrage, became increasingly frustrated with Hausner, describing his parade of survivors as having "no apparent bearing on the case".[lower-alpha 44][304] She was particularly concerned that Hausner repeatedly asked "why did you not rebel?"[305] rather than question the role of the Jewish leaders.[303] On this point, Arendt argued that during the Holocaust some of them cooperated with Eichmann "almost without exception" in the destruction of their own people. These leaders, notably M. C. Rumkowski, constituted the Jewish Councils (Judenräte).[306] She had expressed concerns on this point prior to the trial.[lower-alpha 45][307] She described this as a moral catastrophe. While her argument was not to allocate blame, rather she mourned what she considered a moral failure of compromising the imperative that it is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong. She describes the cooperation of the Jewish leaders in terms of a disintegration of Jewish morality: "This role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter in the whole dark story". Widely misunderstood, this caused an even greater controversy and particularly animosity toward her in the Jewish community and in Israel.[31] For Arendt, the Eichmann trial marked a turning point in her thinking in the final decade of her life, becoming increasingly preoccupied with moral philosophy.[308]

Reception

Arendt's five-part series "Eichmann in Jerusalem" appeared in The New Yorker in February 1963[294] some nine months after Eichmann was hanged on 31 May 1962. By this time his trial was largely forgotten in the popular mind, superseded by intervening world events.[309] However, no other account of either Eichmann or National Socialism has aroused so much controversy.[310] Prior to its publication, Arendt was considered a brilliant humanistic original political thinker.[311] Her mentor, Karl Jaspers, however, had warned her about a possible adverse outcome, "The Eichmann trial will be no pleasure for you. I'm afraid it cannot go well".[lower-alpha 46][248] On publication, three controversies immediately occupied public attention: the concept of Eichmann as banal, her criticism of the role of Israel and her description of the role played by the Jewish people themselves.[313]

Arendt was profoundly shocked by the response, writing to Karl Jaspers "People are resorting to any means to destroy my reputation ... They have spent weeks trying to find something in my past that they can hang on me". Now she was being called arrogant, heartless and ill-informed. She was accused of being duped by Eichmann, of being a "self-hating Jewess", and even an enemy of Israel.[55][311][314] Her critics included The Anti-Defamation League and many other Jewish groups, editors of publications she was a contributor to, faculty at the universities she taught at and friends from all parts of her life.[311] Her friend Gershom Scholem, a major scholar of Jewish mysticism, broke off relations with her, publishing their correspondence without her permission.[315] Arendt was criticized by many Jewish public figures, who charged her with coldness and lack of sympathy for the victims of the Holocaust. Because of this lingering criticism neither this book nor any of her other works were translated into Hebrew until 1999.[316] Arendt responded to the controversies in the book's Postscript.

Although Arendt complained that she was being criticized for telling the truth – "what a risky business to tell the truth on a factual level without theoretical and scholarly embroidery"[lower-alpha 47][317] – the criticism was largely directed to her theorizing on the nature of mankind and evil and that ordinary people were driven to commit the inexplicable not so much by hatred and ideology as ambition, and inability to empathize. Equally problematic was the suggestion that the victims deceived themselves and complied in their own destruction.[318] Prior to Arendt's depiction of Eichmann, his popular image had been, as The New York Times put it "the most evil monster of humanity"[319] and as a representative of "an atrocious crime, unparalleled in history", "the extermination of European Jews".[299] As it turned out Arendt and others were correct in pointing out that Eichmann's characterization by the prosecution as the architect and chief technician of the Holocaust was not entirely credible.[320]

While much has been made of Arendt's treatment of Eichmann, Ada Ushpiz, in her 2015 documentary Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt,[321] placed it in a much broader context of the use of rationality to explain seemingly irrational historical events.[lower-alpha 48][296]

Kein Mensch hat das Recht zu gehorchen

In an interview with Joachim Fest in 1964,[298] Arendt was asked about Eichmann's defense that he had made Kant's principle of the duty of obedience his guiding principle all his life. Arendt replied that that was outrageous and that Eichmann was misusing Kant, by not considering the element of judgement required in assessing one's own actions – "Kein Mensch hat bei Kant das Recht zu gehorchen" (No man has, according to Kant, the right to obey), she stated, paraphrasing Kant. The reference was to Kant's Die Religion innerhalb der Grenzen der bloßen Vernunft (Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason 1793) in which he states:[322]

Der Satz 'man muß Gott mehr gehorchen, als den Menschen' bedeutet nur, daß, wenn die letzten etwas gebieten, was an sich böse (dem Sittengesetz unmittelbar zuwider) ist, ihnen nicht gehorcht werden darf und soll[323] (The saying, "We must hearken to God, rather than to man," signifies no more than this, viz. that should any earthly legislation enjoin something immediately contradictory of the moral law, obedience is not to be rendered)

Kant clearly defines a higher moral duty than rendering merely unto Caesar. Arendt herself had written in her book "This was outrageous, on the face of it, and also incomprehensible, since Kant's moral philosophy is so closely bound up with man's faculty of judgment, which rules out blind obedience."[324] Arendt's reply to Fest was subsequently corrupted to read Niemand hat das Recht zu gehorchen (No one has the right to obey), which has been widely reproduced, although it does encapsulate an aspect of her moral philosophy.[182][325]

The phrase Niemand hat das Recht zu gehorchen has become one of her iconic images, appearing on the wall of the house in which she was born (see Commemorations), among other places.[326] A fascist bas-relief on the Palazzo degli Uffici Finanziari (1942), in the Piazza del Tribunale,[lower-alpha 49] Bolzano, Italy celebrating Mussolini, read Credere, Obbedire, Combattere (Believe, Obey, Combat).[327] In 2017 it was altered to read Hannah Arendt's original words on obedience in the three official languages of the region.[lower-alpha 50][327][328]

The phrase has been appearing in other artistic work featuring political messages, such as the 2015 installation by Wilfried Gerstel, which has evoked the concept of resistance to dictatorship, as expressed in her essay "Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship" (1964).[135][329]

List of selected publications

Bibliographies

- Heller, Anne C (23 July 2005). "Selected Bibliography: A Life in Dark Times". Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Kohn, Jerome (2018). "Bibliographical Works". The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018., in HAC Bard (2018)

- Yanase, Yosuke (3 May 2008). "Hannah Arendt's major works". Philosophical Investigations for Applied Linguistics. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Arendt works". Thinking and Judging with Hannah Arendt: Political theory class. University of Helsinki. 2010–2012. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Books

- Arendt, Hannah (1929). Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin: Versuch einer philosophischen Interpretation [On the concept of love in the thought of Saint Augustine: Attempt at a philosophical interpretation] (PDF) (Doctoral thesis, Department of Philosophy, University of Heidelberg) (in German). Berlin: Springer. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2015., reprinted as

- — (2006). Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin: Versuch einer philosophischen Interpretation (in German). Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 978-3-487-13262-4. Full text on Internet Archive

- Also available in English as:

— (1996). Scott, Joanna Vecchiarelli; Stark, Judith Chelius (eds.). Love and Saint Augustine. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-02596-4. Full text on Internet Archive

- — (1997) [1938, published 1957]. Weissberg, Liliane (ed.). Rahel Varnhagen: Lebensgeschichte einer deutschen Jüdin aus der Romantik [Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess] (Habilitation thesis). Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5587-0. 400 pages. (see Rahel Varnhagen)

- Azria, Régine (1987). "Review of Rahel Varnhagen. La vie d'une juive allemande à l'époque du romantisme". Archives de sciences sociales des religions (Review). 32 (64.2): 233. ISSN 0335-5985. JSTOR 30129073.

- Weissberg, Liliane; Elon, Amos (10 June 1999). "Hannah Arendt's Integrity". The New York Review of Books (Editorial letters). Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Zohn, Harry (1960). "Review of Rahel Varnhagen. The Life of a Jewess". Jewish Social Studies (Review). 22 (3): 180–81. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4465809.

- Azria, Régine (1987). "Review of Rahel Varnhagen. La vie d'une juive allemande à l'époque du romantisme". Archives de sciences sociales des religions (Review). 32 (64.2): 233. ISSN 0335-5985. JSTOR 30129073.

- — (1976) [1951, New York: Schocken]. The Origins of Totalitarianism [Elemente und Ursprünge totaler Herrschaft] (revised ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-54315-4., (see also The Origins of Totalitarianism and Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism) Full text (1979 edition) on Internet Archive

- Riesman, David (1 April 1951). "The Origins of Totalitarianism, by Hannah Arendt". Commentary (Review). Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Nisbet, Robert (1992). "Arendt on Totalitarianism". The National Interest (Review) (27): 85–91. JSTOR 42896812.

- — (2013) [1958]. The Human Condition (Second ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92457-1. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2018. (see also The Human Condition)

- — (1958). Die ungarische Revolution und der totalitäre Imperialismus (in German). München: R. Piper & Co Verlag. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- — (2006) [1961, New York: Viking]. Between Past and Future. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-66265-6. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2018. (see also Between Past and Future)

- — (2006b) [1963, New York: Viking]. On Revolution. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-66264-9. (see also On Revolution) Full text on Internet Archive