In the aftermath of World War I and during the Armenian–Azerbaijani and Russian Civil wars, there were mutual massacres committed by Armenians and Azerbaijanis against each other. A significant portion of the Muslim population (mostly Tatars[lower-alpha 1]) of the Erivan Governorate were displaced during the internecine conflict by the government of Armenia. Starting in 1918, Armenian partisans expelled thousands of Azerbaijani Muslims in Zangezur and destroyed their settlements in an effort to "re-Armenianize" the region. These actions were cited by Azerbaijan as a reason to start a military campaign in Zangezur. Ultimately, Azerbaijan took in and resettled tens of thousands of Muslim refugees from Armenia. The total number of killed is unknown.

Background

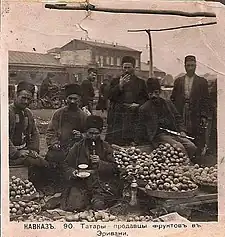

Following the Russian annexation of Iranian Armenia, tens of thousands of Armenians repatriated to Russian Armenia in 1828–1831, thereby regaining an ethnic majority in their homeland for the first time in "several hundred years".[3] Despite this, the Russian Empire census indicated there to be over 240 thousand Muslims on the territory of present-day Armenia in 1897, indicated by previous censuses to be mostly Tatars[lower-alpha 1] (forming over 30 percent of the population).[4] As a result of rising nationalism in the South Caucasus, ethnic clashes erupted between Armenians and Tatars in the Russian Empire between 1905 and 1907, resulting in massacres of thousands of Armenians and Azerbaijanis[5] and the destruction of hundreds of Armenian and Tatar villages.[6]

Until the Ottoman invasion of the South Caucasus in 1918, Armenians and Tatars lived "relatively peacefully" throughout the First World War.[7] Tensions rose after both Armenia and Azerbaijan became briefly independent from Russia in 1918 as both engaged in a war over their mutual borders.[8][9]

Events

Expert on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Thomas de Waal wrote that Azerbaijanis in Armenia became the "collateral victims" of the Armenian genocide carried out by the Ottoman Empire years prior; also adding that despite Azerbaijanis being represented by three delegates in an eighty-seat Armenian parliament, they were universally targeted as "Turkish fifth columnists".[10] In the aftermath of World War I, and during the Armenian–Azerbaijani war and Russian Civil War, there were mutual massacres committed by Armenians and Azerbaijanis against each other.[9] The Erivan Governorate, which formed a part of the Armenian republic,[11] had a "significant Muslim population until 1919."[12]

The British journalist C. E. Bechhofer Roberts commented on the state of affairs in April 1920 as "no day went by without a catalogue of complaints from both sides, Armenian and Tartar, of unprovoked attacks, murders, village burnings and the like. Superficially, the situation was a series of vicious circles. Tartar and Armenian attacked and retaliated for attacks. Fear drove on each side to fresh excesses."[13]

In the Erivan Governorate and Kars Oblast

Mustafa Kemal, the leader of the Turkish National Movement, in justifying an invasion of Armenia, stated that reportedly nearly 200 villages were burned by Armenians and most of their 135 thousand inhabitants were "eliminated".[14] Historian Richard Hovannisian wrote that nearly a third of the 350 thousand Muslims of the Erivan Governorate were displaced from their villages in 1918–1919 and living in the outskirts of Yerevan or along the former Russo-Turkish border in emptied Armenian homes. In 1919, the Armenian government declared the right of return of all refugees, however, this was unimplemented in emptied Muslim settlements occupied by Armenian refugees.[15] During his tenure as minister of war, Rouben Ter Minassian transferred many of the 30 thousand Armenian refugees from eastern Anatolia, to replace evicted Muslims and homogenise certain areas, including Erivan (present-day Ararat) and Daralayaz.[16] Ter Minassian, displeased with the fact that Azerbaijanis in Armenia lived on fertile lands, waged at least three campaigns aimed at cleansing Azerbaijanis from 20 villages outside Erivan, as well as in the south of the country.[10] Oliver Wardrop traveled through Armenia in October 1919 and wrote that along much of Lake Sevan lay deserted houses "in ruins from internecine conflicts between Armenians and Tatars."[17] In October 1919, Muslim authorities in Kars appealed to Azerbaijan for means to transport 25 thousand refugees.[18]

In Zangezur

Throughout 1918–1921, Armenian commanders Andranik Ozanian[19][20][21][22][23][24][25] and Garegin Nzhdeh brought about a "re-Armenianization" of Zangezur[26][27][28][29][30] through the expulsion of tens of thousands[31] (40[32]–50 thousand.[33][34]) A message dated 12 September from the local county chief indicated that the villages of Rut, Darabas, Agadu, Vagudu were destroyed, and Arikly, Shukyur, Melikly, Pulkend, Shaki, Kiziljig, the Muslim part of Karakilisa, Irlik, Pakhlilu, Darabas, Kyurtlyar, Khotanan, Sisian, and Zabazdur were set aflame, resulting in the deaths of 500 men, women, and children.[35] In the Barkushat–Geghvadzor valleys and southeast of Goris, nine villages and forty hamlets were "wiped out" in January 1920 in an act of retribution for the massacre of Armenians in Agulis.[36]

The number of Muslim settlements in Zangezur destroyed by Andranik and Nzhdeh is given by different authors as 24,[32] 49 (9 villages and 40 hamlets),[36] or 115.[33][34] The destruction of these settlements and the restriction imposed by local Armenians on Muslim shepherds taking their flocks into Zangezur was cited by Azerbaijan as the reason for their military campaign against Zangezur in late-1919.[32]

Casualties and displaced persons

| Region | Settlements destroyed | Population displaced |

|---|---|---|

| Erivan Governorate | 135,000[37] | |

| ↳ Surmalu uezd | 24[38]–38[39] | 40,000[39] |

| Kars oblast | 10,000[40] | |

| Zangezur uezd | 49[36]–115[34] | 40,000[32]–50,000[34] |

| TOTAL | 73–153 | 225,000–235,000 |

Aftermath

Following Armenia's sovietisation in 1920, "more than 10 thousand Turks" remained within the borders of Armenia.[41] According to the soviet agricultural census by 1922, 60 thousand Azerbaijani refugees (also known as Turko-Tatars[lower-alpha 1]) repatriated, bringing their total up to 72,596 - 77,767.[41][42] In April 1920, the archbishop of Yerevan, Khoren I of Armenia wrote "I must admit that a few Tatar villages...have suffered... but, every time...they were the aggressors, either they actually attacked us, or they were being organised by the Azerbaijan agents and official representatives rise against the Armenian Government." [16] To assist the destitute 70–80 thousand Muslim refugees living south of Yerevan (50 thousand of whom were dependent on relief aid during the winter), the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic transferred large amounts of funds. It was reported in 1919–1920 that there were 13 thousand Muslims in Yerevan and another 50 thousand throughout Armenia. Muslims, in contrast with their coreligionists in the south of the country lived "acceptably" and with "generally cordial" interethnic relations in the north. The 40 thousand Muslims who had fled from Armenia to Azerbaijan were resettled through a 69 million ruble allocation by the Azerbaijani government.[18]

Contemporary assessment

Turkish-German historian Taner Akçam criticized Turkish efforts to equate these events with the previous Armenian genocide. He also criticized the death figures in primary sources for often being "freely invented by the authors" and exaggerations of "destroyed villages" referring to settlements of 4–5 inhabitants.[43]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Before 1918, Azerbaijanis were generally known as "Tatars". This term, employed by the Russians, referred to Turkic-speaking Muslims of the South Caucasus. After 1918, with the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and "especially during the Soviet era", the Tatar group identified itself as "Azerbaijani".[1][2]

References

- ↑ Bournoutian 2018, p. 35 (note 25).

- ↑ Tsutsiev 2014, p. 50.

- ↑ Herzig & Kurkchiyan 2005, p. 66.

- ↑ Korkotyan 1932, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1967). Armenia on the road to independence 1918. Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of Calif. Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-520-00574-7.

64 Filip Makharadze, Ocherki revoliutsionnogo dvizheniia v Zakavkaz'e (Tiflis, 1927), pp. 300, 307, gives the number killed in Baku in February, 1905, as more than 1,000, most of whom were Armenian, while he contends that the total losses for 1905-1907 were more than 10,000 killed and 15,000 uprooted. E. Aknouni, Political Persecutions: Armenian Prisoners of the Caucasus (New York, 1911), p. 30, states that 128 Armenian and 158 Tatar villages were sacked and ruined. Ananun, op. cit., p. 180, calculates that no fewer than 1,500 Armenians and 1,600 Tatars were killed, and that the Armenians sustained more than 75 percent of the property damage.

- ↑ Aknouni, E. (2018-05-01). Political Persecution: Armenian Prisoners of the Caucasus;. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-0-332-92636-0.

In the years 1935 and 1906 at the sad conflicts of the Armenians and the Tartars 286 villages were sacked and ruined of which number 128 were inhabited by Armenians, 158 by Turks. The number of injured families was 14760. Of these 7265 were Armenians, while 7495 Tartars. The destroyed cities were Baku, Shushy, Ganzak, Erivan, Hitt Nakhitchevan, Khazak and Tiflis. The number of injured is again im-mense. The number of Armenians killed are the following: Baku, 176; Shushy, 126; Ganzak, 132; Hin Nakhitchevan, 55. The villages around Shushy, 16o; Minken, 198. The villages of Ganzak, 212. The villages of Nakhitchevan, 114

- ↑ Wright 2003, p. 98.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 Kaufman 2001, p. 58.

- 1 2 de Waal 2015, p. 75.

- ↑ Herzig & Kurkchiyan 2005, p. 110.

- ↑ Bournoutian 2015, p. 33.

- ↑ Roberts, Carl Eric Bechhofer (2018-10-16). In Denikin's Russia And The Caucasus, 1919-1920: Being A Record Of A Journey To South Russia, The Crimea, Armenia, Georgia, And Baku In 1919 And 1920. Franklin Classics. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-343-44575-1.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1996b, p. 247.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1982, p. 178.

- 1 2 Bloxham 2005, p. 105.

- ↑ Lieberman 2013, p. 136.

- 1 2 Hovannisian 1982, p. 182.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, pp. 127–129.

- ↑ Arslanian 1980, p. 93.

- ↑ Namig 2015, p. 240.

- ↑ Gerwarth & Horne 2012, p. 179.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1971, p. 87.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1982, p. 207.

- ↑ Leupold 2020, p. 24.

- ↑ Broers 2019, p. 4.

- ↑ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian, Patrick; Mutafian, Claude (1994). The Caucasian Knot: The History & Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. London. ISBN 978-1-85649-287-4.

...it is undeniable that if Zangezur has since been an integral part of Soviet Armenia, it was Nzhdehwho made it possible. Following Andranik, he successfully implemented a 're-Armenianization' of the region...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Chorbajian 1994, p. 134.

- ↑ Zakharov 2017, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Ovsepyan 2001, p. 224.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Hovannisian 1982, p. 213.

- 1 2 Mammadov & Musayev 2008, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 Balayev 1990, p. 43.

- ↑ Buldakov 2010, pp. 893–894.

- 1 2 3 Hovannisian 1982, p. 239.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1996b, p. 147.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1982, p. 106.

- 1 2 Chmaïvsky 1919, p. 8.

- ↑ Hovannisian 1996a, p. 122.

- 1 2 Korkotyan 1932, p. 184.

- ↑ Korkotyan 1932, p. 167.

- ↑ Akçam 2007, p. 330.

Bibliography

- Akçam, Taner (2007). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0805079326.

- Akouni, E. (2011). Political Persecution: Armenian Prisoners Of The Caucasus (a Page Of The Tzar's Persecution). Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1179951164.

- Arslanian, Artin H. (1980). "Britain and the question of Mountainous Karabagh". Middle Eastern Studies. 16 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1080/00263208008700426. ISSN 0026-3206.

- Balayev, Aydyn (1990). Азербайджанское национально-демократическое движение 1917-1929 гг [The Azerbaijani national-democratic movement in 1917–1929] (in Russian). Baku. ISBN 978-5-8066-0422-5. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927356-1. OCLC 57483924.

- Bournoutian, George (2015). "Demographic Changes in the Southwest Caucasus, 1604–1830: The Case of Historical Eastern Armenia". Forum of EthnoGeoPolitics. Amsterdam. 3 (2). ISSN 2352-3654.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2018). Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900–1914. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-06260-2. OCLC 1037283914.

- Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinburgh, UK. ISBN 978-1-4744-5054-6. OCLC 1127546732.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Buldakov, V. P. (2010). Хаос и этнос. Этнические конфликты в России, 1917-1918 гг [Chaos and ethnicity: Ethnic conflicts in Russia, 1917–1918] (in Russian). Moscow: Novy khronograf. ISBN 978-5-94881-160-4. OCLC 765812131.

- Chmaïvsky, Imprimerie H. (1919). L'Etat du Sud-Ouest du Caucase [Southwestern Caucasus State] (in French). Batoum: le Comité central pour la défense des intérêts de la population du Sud-Ouest. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Chorbajian, Levon (1994). The Caucasian Knot: The History & Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. Patrick Donabédian, Claude Mutafian. London: Atlantic Highlands, NJ. ISBN 1-85649-287-7. OCLC 31970952.

- Coyle, James J. (2021). Russia's Interventions in Ethnic Conflicts: The Case of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-59573-9. ISBN 978-3-030-59572-2. S2CID 229424716.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814719459.

- de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-935070-4. OCLC 897378977.

- Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John, eds. (2012). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191626531. OCLC 827777835.

- Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina (2005). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-203-00493-0. OCLC 229988654.

- Hovannisian, Richard G (1967). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520005747. OCLC 1028172352.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918–1919. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520019843.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia: From Versailles to London, 1919–1920. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520041868.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996a). The Republic of Armenia: From London to Sèvres, February–August 1920. Vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520088030.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996b). The Republic of Armenia: Between Crescent and Sickle: Partition and Sovietization. Vol. 4. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520088047.

- Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8736-1.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921). New York City: Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0-95-600040-8.

- Korkotyan, Zaven (1932). Խորհրդային Հայաստանի բնակչությունը վերջին հարյուրամյակում (1831-1931) [The population of Soviet Armenia in the last century (1831–1931)] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Pethrat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2022.

- "Les musulmans en Arménie". Le Temps. 25 July 1920.

- Leupold, David (2020). Embattled Dreamlands: the Politics of Contesting Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish Memory. New York. ISBN 978-0-429-34415-2. OCLC 1130319782.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Levene, Mark (2013). Devastation: The European Rimlands 1912–1938. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191505546.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-3038-5. OCLC 866448976.

- Mammadov, Ilgar; Musayev, Tofik (2008). Армяно-азербайджанский конфликт: История, Право, Посредничество [Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict: history, law, mediation] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Baku: Graf and K Publishing House. ISBN 9785812509354.

- Namig, Sadiqova Sayyara (2015). "Unforgettable Azerbaijani painter Huseyn Aliyev". Problemy Sovremennoy Nauki I Obrazovaniya. 12 (42). ISSN 2304-2338.

- Ovsepyan, Vache (2001). Гарегин Нжде и КГБ [Garegin Nzhdeh and the KGB] (in Russian). Yerevan. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tarasov, Stanislav (7 July 2014). "Зачем Азербайджану Новая "Историческая Родина"" [Why does Azerbaijan need a new 'historical homeland']. iarex.ru. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus (PDF). Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300153088. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2023.

- Volkova, Nataliya G. (1969). Gardanov, V. K. (ed.). Кавказский этнографический сборник [Caucasian ethnographical collection] (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. 4. Moscow: Nauka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2022.

- Wright, John (2003). Transcaucasian Boundaries. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0805079326.

- творчество (Фольклор), Народное (2018). Andranik. Armenian Hero. New York: ЛитРес. ISBN 9785040624676.

- Zakharov, Nikolay (2017). Law, Ian (ed.). Post-Soviet Racisms. Leeds, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-47692-0. OCLC 976083039.