| May Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War | |||||||

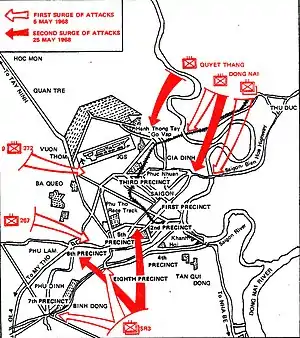

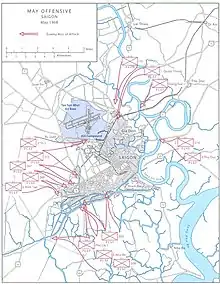

May Offensive attacks on Saigon | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

U.S./South Vietnamese body count: 24,000+ killed 2,000+ captured | ||||||

| Civilian: 421 killed | |||||||

Phase Two of the Tet Offensive of 1968 (also known as the May Offensive, Little Tet, and Mini-Tet) was launched by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and Viet Cong (VC) against targets throughout South Vietnam, including Saigon from 29 April to 30 May 1968. The May Offensive was considered much bloodier than the initial phase of the Tet Offensive. U.S. casualties across South Vietnam were 2,169 killed for the entire month of May, making it the deadliest month of the entire Vietnam War for U.S. forces, while South Vietnamese losses were 2,054 killed. PAVN/VC losses exceeded 24,000 killed and over 2,000 captured. The May Offensive was a costly defeat for the PAVN/VC.

Background

In late March 1968 COSVN and B2 Front leaders held meetings to review the results of the Tet Offensive. Lê Duẩn, the driving force behind the Tet Offensive, and General Hoàng Văn Thái wished to renew the offensive before the start of the southern monsoon began in mid-May in order to improve their position at the Paris Peace Talks which were about to commence. Some field commanders opposed any renewed offensive citing the heavy losses suffered by the VC and resulting poor morale, the inexperience of replacement PAVN troops and logistics problems, while Allied post-Tet operations Truong Cong Dinh and Quyet Thang meant that "there was no longer any opportunity to liberate the cities and province capitals" with a Tet-style offensive. COSVN leaders ignored these objections believing that the element of surprise meant they still had the advantage over Allied forces and recommended to the Politburo that the offensive should be renewed. After consulting with the other fronts in South Vietnam, the Politburo instructed the PAVN high command to begin planning the new offensive.[1]: 529 Part of the offensive was meant to "bring the war to the enemy's own lair", meaning to shift the battlefield from the countryside to significant urban attacks, with the resulting damage inflicted upon urban centres.[2] The targets of the attack was more limited than the Tet Offensive, but still primarily aimed at attacks throughout Saigon and major urban centres.[2]

Unlike the original Tet Offensive which sought to seize nearly every major city in South Vietnam in the hope of provoking a general uprising among the population, the new offensive only involved an assault on Saigon with other towns and cities being harassed by mortars, rockets and artillery fire. Approximately 60,000 PAVN/VC soldiers would take part in the offensive including 30 PAVN infantry regiments, 4 artillery regiments, 3 composite PAVN/VC infantry regiments and 10 VC provincial infantry battalions. The major targets would be Saigon and Đông Hà near the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Regimental-strength operations were planned in Bình Định and Kon Tum Provinces.[1]: 529–30

On 19 April the PAVN chief political officer of Sub-Region 1, Lt. Col. Tran Van Dac, surrendered to South Vietnamese forces in Bình Dương Province. Dac revealed that the PAVN/VC planned to attack Saigon and other targets across the country at the end of April. After 2 days of questioning, U.S. and South Vietnamese intelligence concluded that Dac was telling the truth and his information and other signals and human intelligence led COMUSMACV General William Westmoreland to advise his senior commanders that another offensive was imminent and instruct them to move forces back to defend Saigon. News of Dac's defection leaked within days and the Politburo decided to proceed with the offensive given that Dac's knowledge was limited to the planned attacks on Saigon but to delay the start of the offensive by 1 week, other than around the DMZ, in the hope that the Allies would think the Saigon attack had been cancelled and lower their guard.[1]: 530–1 [3]: 20

Offensive

DMZ

On 29 April the PAVN 320th Division attacked An Binh, north of Đông Hà Combat Base, this drew two Battalions of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) 2nd Regiment into a running battle and the 1st Battalion 9th Marines was sent in to support the ARVN resulting in a 7-hour long battle that left 11 Marines, 17 ARVN and over 150 PAVN dead.[4]: 292 The following day the 3rd Battalion 9th Marines arrived to support the Marine/ARVN force and was ambushed north of Cam Vu, 20 Marines and 41 PAVN were killed.[4]: 293 Also on 30 April, a PAVN unit opened fire on a US Navy Clearwater patrol from entrenched positions near Dai Do, 2.5 km northeast of Đông Hà. It was later discovered that four PAVN Battalions including the 48th and 56th from the 320th had established themselves at Dai Do.[4]: 294 The Battle of Dai Do lasted until 3 May and resulted in 81 Marines and over 600 PAVN killed.[4]: 295–304 The PAVN engaged US and ARVN forces elsewhere around Đông Hà from 4–6 May, on the evening of 6 May the 2nd Brigade 1st Cavalry Division was deployed into Tru Kinh to conduct Operation Concordia Square and on 9 May was ambushed by a PAVN force resulting in 16 U.S. dead for the loss of 80 PAVN. On 10 May a night attack north of Nhi Ha was broken up by air, artillery and naval support, 159 PAVN were killed. After this the 320th had broken into small groups and was moving back towards the DMZ, from 9–17 May the 2nd Brigade reported killing 349 PAVN for the loss of 28 killed.[4]: 306

While it seemed that the 320th had abandoned their attempts to take Đông Hà, this was just a temporary lull. On 22 May a unit from the 320th ran into a Company from 3rd Battalion 3rd Marines between Con Thien and Gio Linh and was caught in the open by Marine artillery and air support.[4]: 308 East of Con Thien the 1st Battalion 4th Marines encountered another PAVN unit setting off a two-day battle as the PAVN tried to escape back through the DMZ resulting in 23 Marines and 225 PAVN killed.[4]: 308–9 On 25 May in actions at Dai Do and Nhi Ha 350 PAVN were killed.[4]: 309 In two actions at Tru Kinh on 26 May over 56 PAVN were killed for the loss of 10 Marines, while the ARVN killed 110 PAVN north of Thuong Nghia.[4]: 309 On 27 May the Marines killed 28 PAVN and by 30 May the 320th was attempting to escape through the Marine and ARVN cordon. Total PAVN losses in the second Battle of Đông Hà were over 1000 killed.[4]: 309–10

Saigon

First wave

At 04:00 on 5 May a VC unit attacked ARVN positions at the Newport Bridge and simultaneously VC wearing Marine uniforms attacked Marine positions closer to the city centre. At 04:30 a battalion sized VC force was engaged near the Phú Thọ Racetrack where heavy fighting had taken place during the Tet Offensive. At 10:00 the ARVN Airborne was engaged by VC north of Tan Son Nhut Air Base.[3]: 22 Two battalions of the VC 271st Regiment followed by another regiment, attacked eastward in the ARVN 5th Ranger Group's Cholon sector. Using small arms, automatic weapons, and rocket fire, they attempted to seize the headquarters of the 6th Police Precinct. Throughout the morning, the 30th Ranger Battalion was heavily engaged with forces of the 3rd Battalion, 271st Regiment, less than 3 km due west of the Phú Thọ Racetrack. Although the Rangers had managed to slow the VC with artillery and helicopter assistance, the fight was still raging in the early afternoon. UH-1 Huey helicopter gunships of the 120th Aviation Company Gunship Platoon at Tan Son Nhut AB were called in to support the Rangers and they hit the VC positions, one gunship was hit by VC fire and crash-landed and burnt on the ground while the crew escaped unharmed.[5]

On 6 May the 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment was engaged by a VC force near the village of Ap Hoa Thanh on the western edge of Saigon.[3]: 22–3 The ARVN 30th and 33rd Ranger Battalions joined with US Cavalry forces to attack a hamlet west of Phú Thọ Racetrack, meeting heavy resistance they withdrew and called in air and artillery strikes, on entering the hamlet the next morning they counted over 200 VC dead.[3]: 23 A unit from the 199th Light Infantry Brigade was engaged by VC forces in a hamlet west of Saigon starting a 3 day running battle, after multiple air and artillery strikes the US force overran the village, finding concrete-reinforced bunkers which had only been destroyed by delayed-fuze 750 lb bombs.[3]: 24–5

On 7 May the 35th Ranger Battalion, who had established a cordon with the National Police north of Cholon, were ordered to attack VC positions to the north. They were met by heavy fire including B-40 rockets described by their US adviser as "coming in like hail". The Rangers withdrew to allow airstrikes against the VC and assaulted again but were again stopped by heavy fire.[3]: 25–6 On 8 May the 38th Ranger Battalion relieved the 35th Rangers and attempted to restart the advance but made little progress until aided by US Cavalry forces. The assault slowly continued on 9 May finding 45 VC dead.[3]: 26

From 7–12 May in the Battle of South Saigon units of the US 9th Infantry Division fought off 4 VC battalions as they tried to attack the city from the south killing 200-250 VC.[1]: 575–83

On 10 May the 33rd Rangers swept the area around Phú Thọ Racetrack finding 9 VC dead and various weapons and supplies.[3]: 26

On 11 May the 38th Rangers continued advancing to the north supported by airstrikes. The VC began to disengage across Saigon and the attack was largely over. The 3/4 Cavalry withdrew from the area and its area of operations was taken over by the Rangers.[3]: 25–7

At 02:45 on 12 May VC sappers attacked the Newport Bridge, detonating explosive charges on two of the bridge piers causing a 100-foot (30 m) section of the north lane to drop into the river below, the VC withdrew by 04:00. The 33rd Rangers continued their sweeps around Phú Thọ finding a further 100 VC dead.[3]: 27–8

VC losses in and around Saigon between 5 and 13 May amounted to 3,058 dead[6][3]: 32 and 221 captured[3]: 32 [7] ARVN losses were 90 dead and 16 missing while US losses were 76 dead and 1 missing.[3]: 32

VC/PAVN forces evacuating east from Saigon engaged the 1st Australian Task Force in the Battle of Coral–Balmoral from 12 May to 6 June.

Second wave

The second phase began on the night of 24–25 May when the K3 and K4 Battalions of the Dong Nai Regiment and the K1 and K2 Battalions from the 1st Quyet Thang Regiment entered Gia Định City, a northern suburb sandwiched between Gò Vấp District and downtown Saigon. Even though the four battalions had only 80-100 men apiece, they had orders to attack the town’s large police headquarters, seize a pair of bridges that led into downtown Saigon, and then take over the city’s radio and television stations. The VC had hardly set foot in Gia Định City when they were assailed by the South Vietnamese 1st and 6th Marine Battalions. The 436th Regional Forces Company and National Police joined the hunt, while the ARVN 1st, 5th and 11th Airborne Battalions sealed off the edges of the suburb. The VC lost at least 40 killed on the first day, including the regimental commander and the senior political officer of 1st Quyet Thang Regiment. The list of VC troops killed or captured grew in the coming days. Among those taken prisoner were the executive officer of the K3 Battalion and the political officer of the K4 Battalion, who provided valuable intelligence about the VC’s plans. By 1 June, the four battalions had been reduced to just 70 healthy soldiers and 30 wounded men who could still fight.[1]: 585–6

The western thrust against Saigon began on the night of 26–27 May. The 273rd Regiment headed toward Phu Lam alongside the 6th Binh Tan and 308th Battalions, the latter unit having just arrived from the delta. The Vietnamese 2nd Marine Battalion bore the brunt of the initial assault. The 2nd Battalion, 273rd Regiment, attacked the 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, which was camped some six kilometers west of Saigon. The VC broke contact after ninety minutes, but the battalion caught up with them at daybreak. Reinforced by Troops A and C of the 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, the Americans nearly annihilated the 2nd Battalion, killing 243 VC while losing 6 killed and 28 wounded. As the fighting increased around Phu Lam, the ARVN 38th Ranger Battalion, minus one company, and the reconnaissance company from the ARVN 5th Ranger Group rushed in to help the South Vietnamese marines. Aided by gunships, the two battalions took 23 prisoners and killed around 370 VC over the next four days. Nevertheless, the VC showed great determination, and approximately 200 troops, mostly from the 6th Binh Tan Battalion, managed to slip past the allied screen into Cholon. At first the National Police took responsibility for tracking down the intruders. When dozens of VC remained at large several days later, the ARVN 30th Ranger Battalion sent a reinforced company and its headquarters element to deal with the threat. On 1 June, the Rangers and National Police sealed off an area approximately twelve square blocks where the VC were most active. Pinning them down was another matter as they rarely operated in teams greater than 6 men and moved around frequently. The VC also took to demolishing the thin walls that divided most row houses so that they could move from one building to another without being seen from the street, some even travelled through the sewer system. Two more companies from the 30th Ranger Battalion joined the hunt on 2 June, squeezing the contested area to just a few square blocks. Many high-ranking government officials showed up to witness the VC’s final destruction. At the request of the ARVN battalion commander, the senior US adviser called in helicopter gunships to eliminate the few remaining VC strong points so the Rangers could avoid further casualties. At around 17:40, a gunship from the 120th Assault Helicopter Company fired a 2.75-inch rocket that struck a building that contained the forward command post of the 30th Ranger Battalion. The blast killed 6 high-ranking South Vietnamese officials including Saigon Police chief Lt Col Nguyen Van Luan and wounding 4.[3]: 35–6 Since most of the dead were political allies of Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, a rumor spread that President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu had orchestrated the attack to weaken his long-time rival. A US Army investigation concluded that a faulty rocket engine had been to blame. The 35th Ranger Battalion took over from the weary 30th Ranger Battalion on 4 June and kept whittling away at the VC’s enclave until the last strongpoint fell on 7 June. A handful of VC troops managed to slip through the cordon and flee back to the countryside, but most of the 200 soldiers who had entered Cholon were now either dead or captured. Among the dead was the deputy commander of Sub-Region 2, Col. Vo Van Hoang, who had led the 6th Binh Tan Battalion and the 308th Battalion into Saigon.[1]: 586–8 National Police chief General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan would be injured in fighting in Cholon, losing a leg after being hit by machine gun fire.

All told, the second phase of fighting in the Capital Military District between 28 May and 10 June cost the VC an estimated 600 killed and another 107 captured. The South Vietnamese lost 42 killed and 142 wounded in Saigon during the same time frame.[1]: 589

On 18 June 152 members of the VC Quyet Thang Regiment surrendered to ARVN forces, the largest communist surrender of the war.

Huế

In late April I Field Force, Vietnam commander General William B. Rosson instructed the commander of the 101st Airborne Division MG Olinto M. Barsanti to deploy his forces to prevent a possible attack on Huế. MG Barsanti ordered his 2nd Brigade to move from the hills west of Huế to the lowlands surrounding the city.[1]: 537

On 28 April the ARVN 1st Division's elite Hac Bao Company located the 8th Battalion, 90th Regiment in the fishing hamlet of Phuoc Yen 6 km northwest of Huế. Units from the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 501st Infantry Regiment surrounded the hamlet and destroyed the battalion in a four day long battle. PAVN losses 309 killed (including all the senior officers) and 104 captured.[1]: 538

On 2 May a Regional Force company reported that PAVN were in the hamlet of Bon Tri, 6 km west of Huế that had been used as a supply station during the Battle of Huế. Several companies from the 1st Battalion, 505th Infantry Regiment and the Hac Bao Company engaged the PAVN 3rd Battalion, 812th Regiment in a two day battle resulting in 121 PAVN dead for Allied losses of four killed and 18 wounded.[1]: 538

On 5 May elements of the 101st Airborne Division engaged the 7th Battalion, 29th Regiment, near Firebase Bastogne, killing 71 PAVN. Another 101st Airborne Division unit engaged the 7th Battalion, 90th Regiment in the hamlet of Thon La Chu northwest of Huế, which had been a PAVN/VC stronghold during the Battle of Huế, killing 55 PAVN.[1]: 538

On 19 May, a PAVN rocket attack on Camp Evans caused an ammunition dump to explode starting a fire that spread to the airfield damaging or destroying 124 aircraft of the 1st Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division rendering the brigade combat ineffective for a week until replacement helicopters arrived.[1]: 539

Allied spoiling operations, in particular Operation Carentan and Operation Delaware had so disrupted the PAVN logistic network that the PAVN's Military Region Tri-Thua-Thien headquarters was unable to mount any major attack on Huế.[1]: 539

Da Nang

PAVN/VC operations against Da Nang were forestalled by the 1st Marine Division's Operation Allen Brook from 4 May to 22 August on Go Noi Island 25 km south of Da Nang which resulted in 917 PAVN/VC killed and 11 captured for the loss of 172 Marines killed[4]: 328–43 and Operation Mameluke Thrust from 19 May to 23 October in Happy Valley southwest of Da Nang which resulted in 2,728 PAVN killed and 47 captured for the loss of 269 Marines.[4]: 338–48

Khâm Đức

The PAVN's main objective in southern I Corps was to destroy the Khâm Đức Special Forces camp in western Quảng Tín Province to create an infiltration route from Laos to the Quế Sơn Valley.[1]: 539 While the U.S. initially planned to build up forces for a major battle at Khâm Đức, they then decided to withdraw rather than tie down their forces in what could become a prolonged siege as had just ended at Khe Sanh. In a battle that lasted from 10 to 12 May the PAVN overran the outposts surrounding Khâm Đức and harried the withdrawing U.S. and ARVN forces.

In the Battle of Landing Zone Center from 5–25 May the PAVN 31st Regiment lost 365 killed.

Bình Định Province

In the Battle of An Bao from 5–6 May elements of the PAVN 3rd Division ambushed a unit of the 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry Regiment (Mechanized) losing 117 killed for the loss of 18 U.S. killed.[1]: 548–52

On 10 May the PAVN 2nd Regiment was seen near the hamlet of Trung Hoi (2), west of Landing Zone Uplift. On the morning of 11 May Companies B and C, 1/50th Infantry and 2 M42 Dusters moved along Route 506 4 km west of LZ Uplift to investigate the sighting finding an abandoned battalion-size trench complex off Route 506. Forming 2 separate defense perimeters 650m apart they sent out scouts to explore the area. At 11:00 the scouts reported seeing PAVN on Route 506 and then both defensive positions came under heavy fire. Company B made a fighting withdrawal to Company C's position. The PAVN pounded the combined perimeter, a rocket-propelled grenade hit the Company B command vehicle and PAVN fire disabled half the .50-caliber machine guns in Company C and many of the M60 machine guns overheated from continuous firing. Air and artillery support was soon brought in allowing the two companies were able to withdraw down Route 506 to Trung Hoi (2) where they were resupplied and the wounded evacuated. A platoon of M48 tanks from the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor Regiment arrived at Trung Hoi (2) and the force regained contact with the PAVN at 16:40. At 18:40 the force pulled back for resupply and the PAVN moved into the surrounding hills. On the morning of 12 May the force moved back up Route 506 with the US claiming 61 PAVN killed, but it was estimated that the PAVN had removed at least a further 140 dead. U.S. losses were 3 killed and 40 wounded.[1]: 552–3

After receiving intelligence that the 2nd Regiment was in the village of Trinh Van, on 25 May Company B and several platoons from Company C, 1/50th Infantry were sent up Route 506 to investigate. The convoy turned off Route 506 2 km southeast of Trinh Van and moved across rice paddy towards the village. At 11:00 as they approached the hamlet of Trinh Van (1), the PAVN opened fire from a line of bunkers. Company B attempted to move around the PAVN right flank, but the company command vehicle took a direct hit from a 60-mm. mortar shell killing the artillery forward observer and wounding several other crewmen. Company B then tried to assault the left flank, but was similarly repulsed by heavy PAVN fire and pulled back to resupply, evacuate wounded and await support. The reconnaissance platoon of 1/50th Infantry and a platoon of 1/69th Armor M48s were sent as reinforcements from Landing Zone Uplift and airstrikes hit the PAVN bunker line. The PAVN sent forward a number of 2-man antitank teams armed with rocket-propelled grenades to attack the U.S. armor, but they were all killed by the airstrikes or machine gun fire. At 16:12 the attack on Trinh Van (1) resumed but PAVN fire again forced the Americans back and they disengaged and established a night defensive position. On the morning of 26 May the U.S. force approached Trinh Van (1) and found that the PAVN had abandoned the position overnight leaving 38 dead. U.S. losses were 1 killed and 20 wounded.[1]: 554–5

The battle at Trinh Van (1) was the last major engagement of the May Offensive in Bình Định Province, having failed to destroy the 1/50th Infantry or disrupt the pacification programme, the 2nd and 22nd Regiments were ordered to move north into Quảng Ngãi Province while the 18th Regiment would remain to defend the 3rd Division's bases.[1]: 555

Kon Tum Province

On 5 May PAVN artillery hit Kon Tum, Pleiku and Buôn Ma Thuột causing little damage. A battalion from the 32nd Regiment attacked a convoy on Highway 14 south of Kon Tum, but the ambush was quickly broken up by the arrival of the ARVN 3rd Armored Cavalry Squadron. PAVN losses were 122 killed, while U.S. losses were nine killed and 16 missing.[1]: 556

At 04:45 on 5 May, a PAVN battalion from the 325C Division assaulted Hill 990 (14°50′35″N 107°37′01″E / 14.843°N 107.617°E), a small outpost 2 km south of Ben Het Camp manned by a CIDG company and two U.S. advisers.[8]: 239 The PAVN swiftly penetrated the perimeter wire but inexplicably withdrew 10 minutes later. At 07:00, a large PAVN unit attacked the base again and then quickly withdrew leaving 16 dead. 66 of the CIDG had been killed or were missing, while one U.S. adviser was killed and the other missing.[1]: 556

Just before midnight on 9 May a battalion from the 101D Regiment and a sapper company attacked Firebase 25 (14°43′12″N 107°40′52″E / 14.72°N 107.681°E), 3 km northeast of Ben Het Camp defended by Companies C and D, 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment.[8]: 5–180 In a three hour long firefight the defenders repulsed the attack killing 47 PAVN for the loss of three U.S. killed.[1]: 556

On 24 May, General Rosson created Task Force Matthews consisting of five battalions from the 4th Infantry Division and three from the 3rd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division. After 88 B–52 sorties, Task Force Matthews set out to sweep the hills around Đắk Tô.[1]: 556–7

At 17:30 on 25 May, the 95C and 101D Regiments attacked Firebase 29 on Hill 824 (14°39′32″N 107°38′10″E / 14.659°N 107.636°E), 4 km southwest of Ben Het defended by Companies A and C, 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment, elements of the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment and Battery B, 6th Battalion, 29th Artillery Regiment.[8]: 180 The defenders returned fire with their heavy weapons and nearby firebases hit the lower slopes of Hill 824 with their artillery. An AC-47 Spooky gunship arrived overhead and began spraying the surrounding woods with fire. The PAVN assaulted the southwestern perimeter and at around 20:00 sappers from the 120th Sapper Battalion began to demolish the wire with satchel charges, blowing several gaps in the wire. The PAVN infantry then assaulted through the gaps despite heavy defensive fire. PAVN recoilless rifle fire and rocket propelled grenades destroyed the defense bunkers and by 22:00 the PAVN controlled the southern sector. The PAVN then split up with some following a communications trench, overwhelming six bunkers along the way, while others moved further up the hill to attack the command post. While the northern end of the base was also battling the PAVN assault, a small reaction force of 15 men was sent to assist the southern sector, splitting into three five-man sections they hit the PAVN forcing them to retreat into the captured bunkers. The defenders then attacked the bunkers with recoilless rifles, M72 LAW antitank rockets and makeshift incendiary bombs. Outside the base perimeter increased air and artillery support prevented follow-on troops from entering the base and after a final attempt to enter the base at 01:30 the PAVN began to withdraw. By 07:30 all the PAVN within the base had been killed or captured. PAVN losses were 198 killed (while PAVN prisoners indicated that another 150 had been killed) and 300 wounded. U.S. losses were 18 killed and 62 wounded.[1]: 557–8

On 26 May I Field Force received intelligence that the PAVN 21st Regiment, which normally operated in the Que Son Valley, had moved into II Corps and was advancing on the Dak Pek Camp in northwest of Kon Tum Province. Two battalions from the 3rd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division were deployed to secure the high ground overlooking the camp and B–52s sorties hit the surrounding area. The 21st Regiment retreated into Laos.[1]: 558

At 02:30 on 30 May the 101D Regiment began a second attack on Hill 990 hitting the base with 120-mm. mortars and 105-mm. howitzers which provided cover for sappers to penetrate the defensive perimeter. At 05:00, a PAVN battalion assaulted up the hill. The CIDG forces at the base had been replaced by Company D, 3/12th Infantry and their defensive fire forced the PAVN to withdraw by 05:30 leaving 43 dead. U.S. losses were seven killed and 56 wounded.[1]: 558–9

The second battle of Hill 990 marked the end of the May offensive in Kon Tum Province, Task Force Matthews continued to search around Ben Het but it became apparent that the PAVN had withdrawn into Laos and Task Force Matthews was disbanded on 12 June.[1]: 559

Aftermath

The May Offensive was considered much bloodier than the initial phase of the Tet Offensive. Extensive use was made of artillery and airstrikes to dislodge VC who established fighting positions in the stronger concrete buildings within Saigon, with the result that 13,830 homes were destroyed, 421 civilians were killed, 1,444 were wounded and approximately 150,000 were made homeless.[3]: 46 During the period from 5 May to 30 June 997 B-52 sorties were flown within 40 km of downtown Saigon to prevent the VC from massing their troops.[3]: 31–2

U.S. casualties across South Vietnam were 2,169 killed for the entire month of May making it the deadliest month of the entire Vietnam War for U.S. forces, while South Vietnamese losses were 2,054 killed.[9] The US claim that VC/PAVN losses exceeded 24,000 killed and over 2,000 captured. The May Offensive was regarded as a defeat for the PAVN/VC.[10][1]: 589–90

The VC had essentially been ordered "to try to do what they had failed to do with far greater numbers three months earlier". VC General Huynh Cong Than later stated "Our troops could not penetrate any deeper than they had during the first offensive, and in places didn't even get as far as they had the first time."[2] "I still do not understand why we attacked the cities again, when the balance of forces had titled so heavily against us... What led our leaders to believe that millions were boiling with revolutionary zeal and ready to sacrifice everything?!! We found that this was not so."[11] Nevertheless the May Offensive demonstrated that the PAVN/VC could still launch major, nation-scale offensives despite the failure of the original Tet Offensive.[2]

Two and a half months later, another major offensive would be launched, the August Offensive concluding the three offensives of the overall Tet Offensive.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Villard, Erik (2017). United States Army in Vietnam Combat Operations Staying the Course October 1967 to September 1968. Center of Military History United States Army. ISBN 9780160942808.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 Ward, Geoffrey (2017). The Vietnam War: An Intimate History. Knopf. pp. 305–310. ISBN 9780307700254.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Thompson, A.W. (14 December 1968). The Defense of Saigon. Headquarters Pacific Air Force.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Shulimson, Jack (1997). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: 1968 The Defining Year. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. ISBN 0160491258.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Cash, John; Albright, John; Sandstrum, Allan (1970). Seven Firefights in Vietnam (PDF). Department of the Army. pp. 140–52. ISBN 9780486454719.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Hoang, Ngoc Lung (1978). The General Offensives. General Research Corporation. p. 98.

- ↑ Cash, John A.; Albright, John; Sandstrum, Allan W. (1970). Seven Firefights in Vietnam. The United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0486454719. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- 1 2 3 Kelley, Michael (2002). Where we were in Vietnam. Hellgate Press. ISBN 978-1555716257.

- ↑ "The men killed on a single, bloody day in Vietnam, and the haunting wall that memorializes them". The Washington Post. May 25, 2018.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military. ABC-CLIO. pp. 759–60. ISBN 978-1851099610.

- ↑ Hastings, Max (2018). Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975. Harper. p. 489. ISBN 9780062405661.