| Boeing 717 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Boeing 717 of Delta Air Lines, its largest operator | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas Boeing Commercial Airplanes |

| First flight | September 2, 1998[1][2] |

| Introduction | October 12, 1999, with AirTran Airways[2] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Delta Air Lines Hawaiian Airlines QantasLink AirTran Airways (historical) |

| Produced | 1998–2006[2] |

| Number built | 156[3] |

| Developed from | McDonnell Douglas MD-80 |

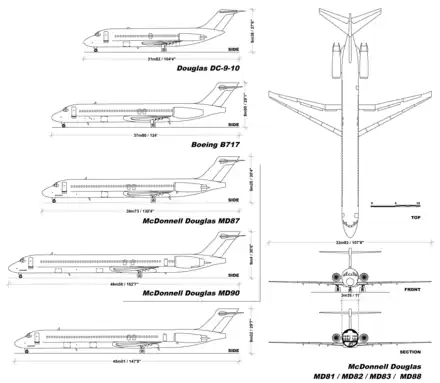

The Boeing 717 is an American five-abreast narrow-body airliner produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes. The twin-engine airliner was developed for the 100-seat market and originally marketed by McDonnell Douglas in the early 1990s as the MD-95 until the company merged with Boeing in August 1997. It was a shortened derivative of McDonnell Douglas’ successful airliner, the MD-80, and part of the company’s broader DC-9 family. Capable of seating up to 134 passengers, the 717 has a design range of 2,060 nautical miles [nmi] (3,820 km; 2,370 mi). It is powered by two Rolls-Royce BR715 turbofan engines mounted at the rear of the fuselage.

The first order for the airliner was placed with McDonnell Douglas in October 1995 by ValuJet Airlines (later AirTran Airways). With the 1997 merger taking place prior to production, the airliner entered service in 1999 as the Boeing 717. Production of the type ceased in May 2006 after 155 were delivered. As of June 2023, 103 Boeing 717 airliners remain in service and have recorded zero fatalities and no hull losses.

Development

Background

Douglas Aircraft launched the DC-9, a short-range companion to its larger four-engine DC-8, in 1963.[4] The DC-9 was an all-new design, using two rear fuselage-mounted Pratt & Whitney JT8D turbofan engines; a small, efficient wing; and a T-tail.[5] The DC-9's maiden flight was in 1965 and entered airline service later that year.[6] When production ended in 1982, a total of 976 DC-9s had been produced.[5]

The McDonnell Douglas MD-80 series, the second generation of the DC-9, began airline service in 1980. It was a lengthened DC-9-50 with a higher maximum take-off weight (MTOW) and higher fuel capacity, as well as next-generation Pratt and Whitney JT8D-200 series engines and an improved wing design.[7] 1,191 MD-80s were delivered from 1980 to 1999.[8]

The MD-90 was developed from the MD-80 series.[9] It was launched in 1989 and first flew in 1993.[10] The MD-90 was longer and featured a glass cockpit (electronic instrumentation) and more powerful, quieter, fuel-efficient IAE V2525-D5 engines, with the option of upgrading to an IAE V2528 engine.[11] A total of 116 MD-90 airliners were delivered.[8]

MD-95

The MD-95 traces its history back to 1983 when McDonnell Douglas outlined a study named the DC-9-90. During the early 1980s, as production of the DC-9 family moved away from the smaller Series 30 towards the larger Super 80 (later redesignated MD-80) variants, McDonnell Douglas proposed a smaller version of the DC-9 to fill the gap left by the DC-9-30. Dubbed the DC-9-90, it was revealed in February 1983 and was to be some 25 ft 4 in (7.72 m) shorter than the DC-9-81, giving it an overall length of 122 ft 6 in (37.34 m). The aircraft was proposed with a 17,000 lbf (76 kN) thrust version of the JT8D-200 series engine, although the CFM International CFM56-3 was also considered. Seating up to 117 passengers, the DC-9-90 was to be equipped with the DC-9's wing with 2 ft (0.61 m) tip extensions, rather than the more heavily modified increased area of the MD-80. The aircraft had a design range of 1,430 nmi (2,648 km; 1,646 mi), with an option to increase to 2,060 nmi (3,815 km; 2,371 mi), and a gross weight of 112,000 lb (51,000 kg).[12]

The DC-9-90 was designed to meet the needs of the newly deregulated American airline industry. However, its development was postponed by the recession of the early 1980s. When McDonnell Douglas did develop a smaller version of the MD-80, it simply shrunk the aircraft to create the MD-87, rather than offer a lower thrust, lighter aircraft that was more comparable to the DC-9-30. With its relatively high MTOW and powerful engines, the MD-87 essentially became a special mission aircraft and could not compete with the all new 100-seaters then being developed. Although an excellent aircraft for specialized roles, the MD-87 often was not sold on its own. Relying on its commonality factor, sales were generally limited to existing MD-80 operators.[13]

In 1991, McDonnell Douglas revealed that it was again considering developing a specialized 100-seat version of the MD-80, initially named the MD-87-105 (105 seats). It was to be some 8 ft (2.4 m) shorter than the MD-87, powered with engines in the 16,000–17,000 lbf (71–76 kN) thrust class.[13] McDonnell Douglas, Pratt & Whitney, and the China National Aero-Technology Import Export Agency signed a memorandum of understanding to develop a 105-seat version of the MD-80. At the 1991 Paris Airshow, McDonnell Douglas announced the development of a 105-seat aircraft, designated MD-95.[13] The new name was selected to reflect the anticipated year deliveries would begin.[14] McDonnell Douglas first offered the MD-95 for sale in 1994.[14][15]

In early 1994, the MD-95 re-emerged as similar to the DC-9-30, its specified weight, dimensions, and fuel capacity being almost identical. Major changes included a fuselage "shrink" back to 119 ft 4 in (36.37 m) length (same as the DC-9-30), and the reversion to the original DC-9 wingspan of 93 ft 5 in (28.47 m). At this time, McDonnell Douglas said that it expected the MD-95 to become a family of aircraft with the capability of increased range and seating capacity.[13] The MD-95 was developed to satisfy the market need to replace early DC-9s, then approaching 30 years old. The MD-95 was a complete overhaul, going back to the original DC-9-30 design and applying new engines, cockpit and other more modern systems.[14]

In March 1995, longtime McDonnell Douglas customer Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) chose the Boeing 737-600 for its 100-seater over the MD-95.[14] In October 1995, U.S. new entrant and low-cost carrier ValuJet signed an order for 50 MD-95s, plus 50 options.[14] McDonnell Douglas president Harry Stonecipher felt that launching MD-95 production on the basis of this single order held little risk, stating that further orders would "take a while longer".[16] The ValuJet order was the only order received for some two years.[15]

Engines

As first proposed, the MD-95 was to be powered by a 16,500 lbf (73 kN) thrust derivative of the JT8D-200 series with the Rolls-Royce Tay 670 also considered as an alternative. This was confirmed in January 1992, when Rolls-Royce and McDonnell Douglas signed a memorandum of understanding concerning the Tay-powered MD-95. McDonnell Douglas said that the MD-95 project would cost only a minimal amount to develop, as it was a direct offshoot of the IAE-powered MD-90.[13]

During 1993 McDonnell Douglas seemed to be favoring a life extension program of the DC-9-30, under the program name DC-9X, to continue its presence in the 100-120 seat market, rather than concentrating on the new build MD-95. In its evaluation of the engine upgrades available for the DC-9X, McDonnell Douglas found the BMW Rolls-Royce BR700 engine to be the ideal candidate, and on February 23, 1994, the BR700 was selected as the sole powerplant for the airliner.[13]

Production site

.jpg.webp)

McDonnell Douglas was planning for MD-95 final assembly to be undertaken in China, as an offshoot of the Trunkliner program, for which McDonnell Douglas had been negotiating to have up to 150 MD-90s built in China. The MD-90 Trunkliner deal was finalized in June 1992, but the contract was for a total of 40 aircraft, including 20 MD-80Ts and 20 -90Ts. The MD-80 has been license built in Shanghai since the 1980s. However, in early 1993, MDC said that it was considering sites outside China, and was later seeking alternative locations for the assembly line. In 1994, McDonnell Douglas sought global partners to share development costs. It also began a search for a low-cost final assembly site. Halla Group in South Korea was selected to make the wings; Alenia of Italy the entire fuselage; Aerospace Industrial Development Corp. of Taiwan, the tail; ShinMaywa of Japan, the horizontal stabilizer; and a manufacturing division of Korean Air Lines, the nose and cockpit.[13]

On November 8, 1994, McDonnell Douglas announced that final assembly would be taken away from the longtime Douglas plant at Long Beach Airport, California. Instead, it selected a modifications and maintenance operation, Dalfort Aviation in Dallas, Texas, to assemble the MD-95. In early 1995, management and unions in Long Beach reached an agreement to hold down wage costs for the life of the MD-95 program and McDonnell Douglas canceled the preliminary agreement with Dalfort.[17]

Rebranding and marketing

After McDonnell Douglas was acquired by Boeing in August 1997,[18][19] most industry observers expected that Boeing would cancel development of the MD-95. However, Boeing decided to go forward with the design under a new name, Boeing 717.[20] While it appeared that Boeing had skipped the 717 model designation when the 720 and the 727 followed the 707, the 717 name was the company's model number for the C-135 Stratolifter military transport and KC-135 Stratotanker tanker aircraft. 717 had also been used to promote an early design of the 720 to airlines before it was modified to meet market demands. A Boeing historian notes that the Air Force tanker was designated "717-100" and the commercial airliner designated "717-200".[21] The lack of a widespread use of the 717 name left it available for rebranding the MD-95.

_at_Baltimore%E2%80%93Washington_International_Airport.jpg.webp)

At first Boeing had no more success selling the 717 than McDonnell Douglas. Even the original order for 50 was no certainty in the chaotic post-deregulation United States airline market. Assembly started on the first 717 in May 1997.[22] The aircraft had its roll out ceremony on June 10, 1998. The 717's first flight took place on September 2, 1998. Following flight testing, the airliner was awarded a type certification on September 1, 1999. Its first delivery was in September 1999 to AirTran Airways, which Valujet was now called. Commercial service began the following month.[1][2][23] Trans World Airlines (TWA) ordered 50 717s in 1998 with an option for 50 additional aircraft.[24]

Boeing's decision to go ahead with the 717 slowly began to pay off. Early 717 operators were delighted with the reliability and passenger appeal of the type and decided to order more. The small Australian regional airline Impulse took a long-term lease on five 717s in early 2000[25] to begin an expansion into mainline routes.[26] The ambitious move could not be sustained in competition with the majors, and Impulse sold out to Qantas in May 2001.[27]

.jpg.webp)

Within a few months, the 717's abilities became clear to Qantas, being faster than the BAe 146, and achieving a higher dispatch reliability, over 99%, than competing aircraft. Maintenance costs are low: according to AirTran Airways, a C check inspection, for example, takes three days and is required once every 4,500 flying hours. (For comparison, its predecessor, the DC-9 needed 21 days for a C check.) The new Rolls-Royce BR715 engine design is relatively easy to maintain. Many 717 operators, such as Qantas, became converts to the plane; Qantas bought more 717s to replace its BAe 146 fleet,[28] and other orders came from Hawaiian Airlines and Midwest Airlines.[29]

Boeing actively marketed the 717 to a number of large airlines, including Northwest Airlines, who already operated a large fleet of DC-9 aircraft, and Lufthansa. Boeing also studied a stretched, higher-capacity version of the 717, to have been called 717-300, but decided against proceeding with the new model, fearing that it would encroach on the company's 737-700 model. Production of the original 717 continued. Boeing continued to believe that the 100-passenger market would be lucrative enough to support both the 717 and the 737-600, the smallest of the Next-Generation 737 series. While the aircraft were similar in overall size, the 737-600 was better suited to long-distance routes, while the lighter 717 was more efficient on shorter, regional routes.[30][31]

Assembly line and end of production

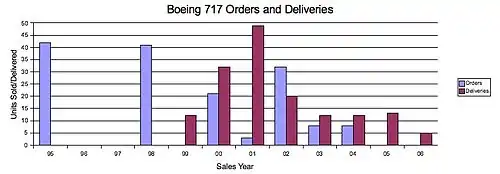

In 2001, Boeing began implementing a moving assembly line for production of the 717 and 737.[32] The moving line greatly reduced production time, which led to lower production costs.[20][33] Following the slump in airline traffic caused by an economic downturn subsequent to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, Boeing announced a review of the type's future. After much deliberation, it was decided to continue with production. Despite the lack of orders, Boeing had confidence in the 717's fundamental suitability to the 100-seat market, and in the long-term size of that market.[34] After 19 worldwide 717 sales in 2000, and just 6 in 2001, Boeing took 32 orders for the 717 in 2002, despite the severe industry downturn.[8] The 100th 717 was delivered to AirTran Airways on June 18, 2002.[35][36][37]

Increased competition from regional jets manufactured by Bombardier and Embraer took a heavy toll on sales during the airline slump after 2001. American Airlines acquired TWA and initially planned to continue the 717 order. American Airlines canceled TWA's order for Airbus A318s, but eventually also canceled the Boeing 717s that had not yet been delivered.[38] The beginning of the end came in December 2003 when Boeing failed to reach a US$2.7 billion contract from Air Canada, a long term DC-9 customer, who chose the Embraer E-Jets and Bombardier CRJ200 over the 717.[39] On January 14, 2005, citing slow sales, Boeing announced that it planned to end production of the 717 after it had met all of its outstanding orders.[40]

The 156th and final 717 rolled off the assembly line in April 2006 for AirTran Airways, which was the 717's launch customer as well as its final customer. The final two Boeing 717s were delivered to customers AirTran Airways and Midwest Airlines on May 23, 2006.[2][3] The 717 was the last commercial airplane produced at Boeing's Long Beach facility in Southern California.[3]

Program milestones

- Announced: June 16, 1991, at the Paris Air Show as MD-95 program by McDonnell Douglas[41]

- Approval to offer: July 22, 1994, McDonnell Douglas received board approval to offer the aircraft.[13][42]

- First order: October 10, 1995, from ValuJet (later to become AirTran Airways) for 50 firm and 50 options for MD-95s[2][42]

- Roll out: June 10, 1998, at Long Beach, California[2][43]

- First flight: September 2, 1998[1][2]

- Certification: FAA: September 1, 1999;[44] EASA (JAA): September 16, 1999[45]

- Entry into service: October 12, 1999, with AirTran Airways on Atlanta-Washington, D.C. (Dulles) route[2][23]

- Last delivery: May 23, 2006, to AirTran Airways.[2][46]

Design

.jpg.webp)

The 717 features a two-crew glass cockpit that incorporates six interchangeable liquid-crystal-display units and advanced Honeywell VIA 2000 computers. The cockpit design is called Advanced Common Flightdeck (ACF) and is shared with the MD-10 and MD-11. Flight deck features include an Electronic Instrument System, a dual Flight Management System, a Central Fault Display System, and Global Positioning System. Category IIIb automatic landing capability for bad-weather operations and Future Air Navigation Systems are available. The 717 shares the same type rating as the DC-9, such that the FAA approved transition courses for DC-9 and analog MD-80 pilots could be completed in 11 days.[47]

In conjunction with Parker Hannifin, MPC Products of Skokie, Illinois designed a fly-by-wire technology mechanical control suite for the 717 flight deck. The modules replaced much cumbersome rigging that had occurred in previous DC-9/MD-80 aircraft. The Rolls-Royce BR715 engines are completely controlled by an electronic engine system (Full Authority Digital Engine Control — FADEC) developed by BAE Systems, offering improved controllability and optimization.[47] The engine claimed significantly lower fuel consumption compared to others then available with the equivalent amount of thrust.[48]

Like its DC-9/MD-80/MD-90 predecessors, the 717 has a 2+3 seating arrangement in the main economy class, providing only one middle seat per row, whereas other single-aisle twin jets, such as the Boeing 737 family and the Airbus A320 family, often have 3+3 arrangement with two middle seats per row.[49][50] Unlike its predecessors, McDonnell Douglas decided not to offer the MD-95/717 with the boarding flexibility of aft airstairs, with the goal of maximizing fuel efficiency through the reduction and simplification of as much auxiliary equipment as possible.[51]

Variants

.JPG.webp)

- 717-200

- Production variant powered by either two Rolls-Royce BR715A1-30 or BR715C1-30 engines with 134 passenger seat, 155 built.

- 717 Business Express

- Proposed corporate version of 717-200, unveiled at the EBACE Convention in Geneva, Switzerland in May 2003. Configurable for 40 to 80 passengers in first and/or business class interior (typically, 60 passengers with seat pitch of 52 in (130 cm). Maximum range in HGW configuration with auxiliary fuel and 60 passengers was 3,140 nmi (5,820 km; 3,610 mi). The version complements BBJ family.[52]

- 717-100 (-100X)

- Proposed 86-seat version, formerly MD-95-20; four frames (6 ft 3 in (1.91 m)) shorter. Renamed 717-100X; wind tunnel tests began in early 2000; revised mid-2000 to eight-frame (12 ft 8 in (3.86 m)) shrink. Launch decision was deferred in December 2000 and again thereafter to an undisclosed date. Shelved by mid-2003.[30]

- 717-100X Lite

- Proposed 75-seat version, powered by Rolls-Royce Deutschland BR710 turbofans; later abandoned.[30]

- 717-300X

- Proposed stretched version, formerly MD-95-50; studies suggest typical two-class seating for 130 passengers, with overall length increased to 138 ft 4 in (42.16 m) by addition of nine frames (five forward and four aft of wing); higher MTOW and space-limited payloads weights; additional service door aft of wing; and 21,000 lb (9,500 kg) BR715C1-30 engines. AirTran expressed interest in converting some -200 options to this model. Was under consideration late 2003 by Star Alliance Group (Air Canada, Austrian Airlines, Lufthansa and SAS); interest was reported from Delta, Iberia and Northwest Airlines.[30][31]

Operators

As of December 2022, there were 103[53] Boeing 717s in service with Delta Air Lines (64), QantasLink (20), and Hawaiian Airlines (19), down from 148 aircraft in 2018.[54]

Delta Air Lines is currently the largest operator of the 717, flying nearly 60 percent of all in-service jets, but did not purchase any of the planes new from Boeing. In 2013, Delta began leasing the entire fleet of 88 jets previously operated by AirTran Airways from Southwest Airlines, who had purchased AirTran, but wanted to preserve its all-Boeing 737 fleet rather than taking on another class of aircraft.[55] For Delta, used Boeing 717 and MD-90s allowed them to retire their DC-9s while also being cheaper to acquire than buying brand-new jets from Airbus or Boeing. Unlike other mainline US legacy carriers, Delta has decided that its best path to profitability is a strategy that utilizes older aircraft, and Delta has created a very extensive MRO (maintenance, repair and overhaul) organization, called TechOps, to support them.[56]

In 2015, Blue1 announced it would sell its 717 fleet, with five jets going to Delta and four going to the then third largest operator of the type, Volotea, a Spanish low-cost carrier.[57]

In January 2021, Volotea retired their last of formerly 19 Boeing 717s. It was the last remaining European operator of the type.[58]

Orders and deliveries

| Total | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 155 | – | – | 8 | 8 | 32 | 3 | 21 | – | 41 | – | – | 42 |

| Deliveries | 155 | 5 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 20 | 49 | 32 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

Accidents and incidents

As of June 2023, the Boeing 717 has been involved in six aviation accidents and incidents but with no hull-losses and no fatalities.[61][62] The major incidents included one on-ground collision while taxiing, an emergency landing where the nose landing gear did not extend, and one attempted hijacking.[61][62]

Specifications

| Variant | Basic | High Gross Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew[63]: 66 | Two | |

| 2-class seating | 106 (8J+98Y @ 36–32 in, 91–81 cm) | |

| 1-class seating | 117Y @ 32 in (81 cm) | |

| Exit limit[63]: 81 | 134 | |

| Cargo | 935 cu ft (26.5 m3) | 730 cu ft (21 m3) |

| Length | 124 ft (38 m) | |

| Wingspan | 93 ft 4 in (28.45 m) | |

| Height | 29 ft 8 in (9.04 m) | |

| Width | Exterior Fuselage: 131.6 in (3.34 m) Interior Cabin: 123.8 in (3.14 m) | |

| Max. takeoff weight | 110,000 lb (50,000 kg) | 121,000 lb (55,000 kg) |

| Empty weight | 67,500 lb (30,600 kg) | 68,500 lb (31,100 kg) |

| Max. payload[63]: 66 | 26,500 lb (12,021 kg) | 32,000 lb (14,515 kg) |

| Fuel weight | 24,609 lb (11,162 kg) | 29,500 lb (13,400 kg) |

| Fuel capacity | 3,673 US gal (13,900 L) | 4,403 US gal (16,670 L)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Turbofans (2×)[63]: 65 | Rolls-Royce BR715-A1-30 | Rolls-Royce BR715-C1-30 |

| Thrust (2×)[63]: 65 | 18,920 lbf (84.2 kN) | 21,430 lbf (95.3 kN) |

| Ceiling[63]: 67 | 37,000 ft (11,000 m) | |

| Cruise speed[12] | Mach 0.77 (822 km/h; 444 kn; 511 mph) at 34,200 ft (10,400 m) | |

| Range[12] | 1,430 nmi (2,648 km; 1,646 mi) | 2,060 nmi (3,815 km; 2,371 mi) |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

Notes

- ↑ Including forward and aft auxiliary fuel tanks

References

- 1 2 3 "Boeing: Historical Snapshot: 717/MD-95 commercial transport". Boeing.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "The Boeing 717". Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Boeing Delivers Final 717s; Concludes Commercial Production in California" (Press release). Boeing. May 23, 2006. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ↑ Endres, Gunter. McDonnell Douglas DC-9/MD-80 & MD-90. London: Ian Allan, 1991. ISBN 0-7110-1958-4.

- 1 2 Norris, Guy and Mark Wagner. "DC-9: Twinjet Workhorse". Douglas Jetliners. MBI Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0676-1.

- ↑ Air International June 1980, p. 293.

- ↑ "Boeing: MD-80 Background". Boeing. Archived from the original on March 2, 1999. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Boeing: Commercial — Orders & Deliveries". Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ↑ Swanborough 1993, p.90.

- ↑ "Boeing: Commercial Airplanes — MD-90 Background". Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing: Commercial Airplanes — MD-90 Technical Characteristics". Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "717-200 technical characteristics" (PDF). Aero. Boeing. July 2002. p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Airclaims Jet Programs 1995

- 1 2 3 4 5 Norris, Guy; Wagner, Mark (1999). Douglas Jetliners. MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0676-1.

- 1 2 Becher, Thomas. Douglas Twinjets, DC-9, MD-80, MD-90 and Boeing 717. The Crowood Press, 2002. ISBN 1-86126-446-1. pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Lopez, Ramon and Guy Norris. "MD-95 Launched with ValuJet". Flight International, October 25–31, 1995.

- ↑ "Business & Technology — Parallels in production: 7E7 and 717 – Seattle Times Newspaper". nwsource.com.

- ↑ Knowlton, Brian (December 16, 1996). "Boeing to Buy McDonnell Douglas". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Boeing: History -- Higher, Faster, Further — The Boeing Company ... The Giants Merge". Archived from the original on January 24, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- 1 2 "Going—but far from gone, 717 innovations live on long after production". Boeing Frontiers magazine, October 2005,

- ↑ "Aerospace Notebook: Orphan 717 isn't out of sequence". seattlepi.com, December 22, 2004.

- ↑ Flight International Commercial Aircraft Page 45 (September 3, 1997)

- 1 2 "Boeing 717 in-service report". Flight International: 42–48. June 5–11, 2001. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ↑ "TWA to Continue Fleet Renewal with Boeing 717-200s".

- ↑ Boeing (April 11, 2000). "Impulse airlines first in Australia with 717s" (Press release). Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ Boeing (January 9, 2001). "Impulse Airlines Boeing 717-200 Cockatoo Takes Off For Home" (Press release). Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ Gaylord, Becky (May 2, 2011). "Qantas to Absorb Competitor As Fare War Takes a Victim". The New York Times. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ↑ Qantas Corporate Communication (October 29, 2004). "QantasLink to Replace BAe146s with Boeing 717s" (Press release). Sydney. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Lamb, Warren (May 28, 2002). "Boeing 717: Designed for Airline Profitability" (Press release). Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Jane's All World Aircraft 2005

- 1 2 "Boeing Releases Proposed 717-300X Rendering" (Press release). September 18, 2003. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Boeing 2001 Annual report Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Boeing's 717 to Hit 100th Delivery". Aero News Network. June 12, 2002. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing Committed To 717 Program And 100-Seat Market". Boeing. Archived from the original on February 17, 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ↑ The Boeing Company (June 18, 2002). "Boeing Delivers 100th 717-200 Twinjet at Ceremony" (Press release). Long Beach, CA: PR Newswire. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing delivers 100th 717-200". Wichita Business Journal. June 18, 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing Delivers 100th 717-200 Twinjet at Ceremony" (Press release). June 18, 2002. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing 717-231 TWA Trans World Airlines | FlyRadius". www.flightrun.com. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Air Canada buying 90 jets from Bombardier, Embraer". CBC News. CBC. December 19, 2003. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ↑ Pae, Peter (January 15, 2005). "Boeing is closing an era in aviation". Business. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ↑ "MDC Steps into 100-seat arena with MD-95". Flight International — Paris Show Report 1991, June 26, 1991, p. 13.

- 1 2 "Classic takes shape". Flight International. April 1, 1998. pp. 31+.

- ↑ Boeing (June 10, 1998). "Boeing Rolls Out First 717-200 Passenger Jet" (Press release). Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ FAA Type Certificate Data Sheets A6WE

- ↑ EASA Type Certificate Data Sheets IM.A.211

- ↑ Boeing delivers final 717 to AirTran, ending Douglas era

- 1 2 Rogers, Ron (March 2000). "Flying the B-717-200". Air Line Pilot: 26. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007.

- ↑ "BMW Rolls-Royce Power Plant for the Boeing 717". boeing.com. Boeing. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ↑ "717-200 Seating Interior Arrangements". Archived from the original on November 22, 2001. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Superior Passenger Seating Comfort 717-200" (PDF). Boeing. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2001. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- 1 2 "717-200 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning". Boeing, May 2011. Retrieved: July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing Introduces 717 Business Express at EBACE 2003". Boeing, May 7, 2003.

- ↑ planespotters.net – Boeing 717 Operators Archived May 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 18, 2022

- ↑ "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Delta to Add Boeing 717 Aircraft to its Fleet". frequentbusinesstraveler.com.

- ↑ "A Look at Delta Air Lines Fleet and Buying Nine MD-90s". March 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Finland's Blue to offload B717 fleet to Volotea, Delta". ch-aviation.

- ↑ Macca, Marco (January 11, 2021). "Volotea: The End of The Boeing 717 in Europe". Airways Magazine. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ↑ 717 Orders and Deliveries, Boeing, archived from the original on January 12, 2016

- ↑ Orders & Deliveries (search) Boeing

- 1 2 "Boeing 717 type list". Aviation-Safety.net, June 28, 2023.

- 1 2 "Boeing 717 type index". Aviation-Safety.net, June 28, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Type Certificate Data Sheet no. A6WE" (PDF). FAA. March 25, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

Further reading

- Norris, Guy (December 6–12, 1995). "T-tail, take three: McDonnell Douglas has finally launched its MD-95 into the hotly contested 100-seat market". Air Transport. Flight International. Vol. 148, no. 4501. Long Beach, California, USA. pp. 46–47. ISSN 0015-3710.

- "717 Passenger Airplane" (PDF). Boeing. 2005.

- "717/MD-95 commercial transport : Historical Snapshot". Boeing.

- "Boeing 717 Production List". Plane spotters.net.