The modern Medicine Wheel symbol was invented as a teaching tool in about 1972 by Charles Storm, aka Arthur C. Storm, writing under the name Hyemeyohsts Storm, in his book Seven Arrows and further expanded upon in his book Lightningbolt.[1][2]: 5,168 It has since been used by various people to symbolize a variety of concepts, some based on Native American religions, others newly invented and of more New Age orientation.[2]: 5,7,181–183,187–189,193,218–219 [3]: 200 It is also a common symbol in some pan-Indian and twelve-step recovery groups.[4]

Recent invention

Charles Storm, pen name Hyemeyohsts Storm, was the son of a German immigrant who claimed to be Cheyenne; he misappropriated and misrepresented Native American teachings and symbols from a variety of different cultures, claiming that they were Cheyenne, such as some symbolism connected to the Plains Sun dance, to create the modern Medicine Wheel symbol around 1972.[1][5][6][7][4] Anthropologist Alice Kehoe suspects that Storm took the idea of the medicine wheel from ahkoiyu, which are little model wheels used in games, and for decoration during rites by the Cheyenne, which were talked about in George Bird Grinnell's 19th century ethnography titled The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways.[3]: 200 [8]: 296,302,314 [9]: 455

Subsequently Vincent LaDuke (a New Age spiritual leader going by the name Sun Bear), who was of Ojibwe descent, started also using the Medicine Wheel symbol, combining the basic concept with pieces of disparate spiritual practices from various Indigenous cultures, and adding elements of new age and occult spiritualism. LaDuke self-published a newsletter and several books, and formed a group of followers that he named the Bear Tribe, of which he appointed himself the medicine chief. For a fee, his mostly wealthy and white followers attended his workshops and retreats, joined his "tribe", and could buy titles and honours that are traditionally reserved for respected elders and knowledge keepers.[1][5][7][4][10][11] For these activities LaDuke was denounced and picketed by the American Indian Movement.[10]

Storm and LaDuke have been described as "plastic medicine men".[10] They and others who have used the medicine wheel symbol to introduce their own ideas and concepts from other cultures into what they claim are Native American and First Nations teachings have been accused by traditional Natives and activists of harming and displacing traditional teachings for financial motives.[10][12][1][13][14][15]

Symbolism

.jpg.webp)

While some Indigenous groups that now use a version of the modern Medicine Wheel as a symbol have syncretized it with traditional teachings from their specific Native American or First Nations culture, and these particular teachings may go back hundreds, if not thousands of years, critics assert that the pan-Indian context it is usually placed in can too easily displace the unique, traditional teachings of sovereign tribes, bands and Nations, and in some cases even replace traditional ways with new age, fraudulent ones.[4]

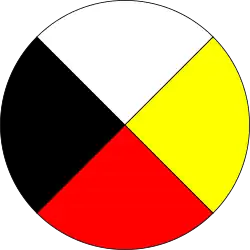

New Age writers tend to centre the idea of the medicine wheel as an individualistic tool of personal development, and use a stylized version with the circle divided into coloured quadrants, with various personal qualities assigned to the colours and quadrants. This redefinition is in stark contrast to the Indigenous view of ceremony and sacred sites being rooted in the community rather than the individual.[16]

Syncretism within the symbol

Many of the concepts introduced into the symbolism of the medicine wheel are arguably not pan-Indigenous and many are not grounded in traditional Indigenous worldviews, though many have to come to view them as such since the advent of the medicine wheel symbol. The typical medicine wheel symbol is divided into four quadrants, each with an associated set of qualities, characteristics, and concepts, with many of these coming from non-Indigenous sources and blended with New Age ideas.[2]

The four elements is a concept adopted from the Ancient Hindu beliefs of Pancha Bhuta and Ancient Greek philosophy of Empedocles.[17][18]

The concepts of the four directions is not in accordance with many Indigenous worldviews that have six directions.[19][20] Moreover, Cheyenne Elders and religious leaders do not typically teach cosmology by referring to the cardinal directions, as Storm did in his book. Rather, they explain cosmology by starting with the vertical, going through the divisions starting with Otatavoom (the Blue Sky-Space) and going to Nasthoaman (the Deep Earth).[21][22] Moreover, the sacred cardinal directions in Cheyenne culture are closer to Northeast, Northwest, Southeast, and Southwest, not the North, South, East, and West as described by Storm.[13]

Though some Indigenous North American cultures, such as the Arapaho, view life as having four stages,[23] the Anishinaabe view life as having seven stages (according to the Miikaans Teaching)[24][25] and the Eastern Cree have five stages.[26]

Though some Indigenous nations have traditional beliefs about people with a different skin colour in their sacred stories, the division of humans into four races is not traditional or universal, but is instead founded in scientific racism and the racist views of early anthropology and biology, notably Carl Linnaeus' classifications as Americanus (red), Europeanus (white), Asiaticus (yellow), and Africanus (black).[27]

The concept of the divisions of the mind, heart/spirit, body, and soul derive from the Ancient Greeks and Christian Neoplatonists.[28]

Some Indigenous nations divide the year into four seasons, but the Cheyenne, which Storm based his book on, have six to eight seasons.[21] Furthermore, the Gwich'in, the Ojibwe, the Cherokee, as well as nations in Virginia and most of the Southeastern US view the year as having five seasons.[29][30][31] Some nations of the Pacific Northwest Coast, such as the Haida, divide the year into two seasons,[31] while the Lakota and Kiowa have four seasons of unequal length,[31][32] and the Woodland Cree have six seasons.[33]

The concept of the year as a wheel can be found in the Wicca and Modern paganism calendar known as the Wheel of the Year, which was published prior to Storm's publishing of the modern Medicine Wheel symbol and concept.[34]

Words for things like "Mother Earth" in Cree (okâwîmâwaskiy) are believed to be a contemporary concept from pan-Indigenous or new age influences because the word does not follow proper Cree grammar, and the classifications of mineral, plant, animal, and human does not fit into many Indigenous language structures.[35][36]

Not all Indigenous nations use the same sacred medicines, as yucca, mescal, and peyote are also considered core sacred medicines by some nations, in addition to the more typically cited sage, cedar, sweet grass, and tobacco.[37] Furthermore, not all Indigenous nations use the four medicines, such as the Coast Salish who traditionally did not use tobacco[38]: 27 , and some Métis Elders who prefer tea and jam, and sometimes a blanket, to being offered tobacco.[39]

Storm has the colours out of order for Cheyenne teachings: East should be red instead of yellow, South should be green not red, and the four colours are white, red, green, and black.[22][40] Furthermore, the Cheyenne colours are not the garish colours used by Storm, but rather earth tones.[13][41][40]

The association of animals, commonly listed as bison, bear, wolf, and deer, (listed as buffalo, eagle, mouse, and bear in Storm's original description[41]) with the quadrants is an example of diluted totemism.[2] In Cheyenne culture, which Storm claimed to base the teachings on, the animal associated with the North is the albino bison, and the dragonfly, vovetass, is associated with both the North and the South because it changes colour during the summer, from green to white.[22]

Though some of the concepts are founded in traditional Indigenous teachings, many are not and have resulted in confusion due to misinformation.[4][11]: 141

Criticism of the medicine wheel

Maliseet academic Andrea Bear Nicholas argues that the broad adoption of the medicine wheel with little critical assessment and historical understanding of its fraudulent origins has effectively and almost totally displaced the unique oral traditions of many Indigenous nations. She views the medicine wheel as another example of ongoing colonial assault against Indigenous cultures, and has criticized academia for not doing more to protect traditional Indigenous cultures.[4]

Co-founder and former president of the American Indian Historical Society, Rupert Costo, heavily criticized Storm's book Seven Arrows in which he introduced his medicine wheel concept, stating that Storm was "vulgarizing one of the most beautiful but least known religions of Man."[15]

"This book, Seven Arrows, will bring disgrace to Harper and Row.... Its content falsifies and desecrates the traditions and religion of the Northern Cheyenne, which it purports to describe. ... If he is indeed Indian (and the tribal chairman states, 'I don't know how he ever got on the rolls,') then shame on him for making a blasphemous travesty of the Cheyenne Way in Seven Arrows. The color plates are a solid disaster, in extremely poor taste, and in fact the end result desecrates the Cheyenne religion. ... The designs are actually blasphemous to Cheyenne religion, portraying Christian religious motifs in the worst possible manner, making a mockery of the religious beliefs and the theological systems of the people. ... There are so many irreligious and irreverent inaccuracies in this book.... to many Cheyenne people ... the reaction to Seven Arrows was disbelief and anger. It was ... based upon a falsification and desecration of Cheyenne beliefs and religion. ... The book is a White Man's interpretation of the Cheyenne. A reader searching for an understanding of the true beauty and profoundly moving religion of the Cheyenne people will not find it in this book. ...this author ... has no religious or secular status in the tribe."

The Northern Cheyenne Tribal Council officially condemned Storm's book Seven Arrows, citing numerous inaccuracies, as did Cheyenne Elders such as Joe Little Coyote. The book's publisher, Harper and Row, paid US$7,500 in reparations (intended to be "all profits presently accrued to Seven Arrows as well as all future profits earned by it.") each to the Northern and Southern Cheyenne, and reclassified the book as fiction.[15][42][22]

"Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of Mr. Chuck Storm's book Seven Arrows is the fact that some of the beliefs which he presents in his book as having been derived from our spiritual ways are completely unfounded and extremely repugnant to the sensitivities of our people who are knowledgeable and qualified to speak about such things, not merely as the product of imagination, but as the result of actual lived experience."

— Elder Joe Little Coyote[15]

In reviewing Storm's book Seven Arrows, anthropologist John H. Moore criticized the book and how Storm inaccurately portrayed Cheyenne culture, skipping over important cultural details practised by Cheyenne cultural teachers, elevating minor elements of Cheyenne religion to undeserved major significance, dismissing cultural values, getting details mixed up, and adding things.

"Several books would be required to correct the compounded inaccuracies of Storm's version of Cheyenne tradition. The frustration of even attempting to do this has prompted a widespread outrage among religious Cheyennes. The Northern Cheyenne Tribal Council has condemned the book and asked that its use be discouraged. The calmest comment that I have received from a Cheyenne is from a member of the Tribal Council who described the book as 'complete B.S. from cover to cover.'"

— John H. Moore[22]

Both Storm and LaDuke have been criticized for commercializing and distorting Indigenous spirituality, including the medicine wheel.[2]: 239 [11]: 13,15 [10]: 324 [3]: 200

Indigenous activists protested and distributed flyers at a lecture given by Storm in San Francisco in February 1995, with the bold title "STOP EXPLOITING THE SACRED TRADITIONS OF AMERICAN INDIAN PEOPLE!!!", which began by saying:

We are members of the Bay Area American Indian community, and we are outraged by non-Indian wannabes and would-be gurus of 'the New Age' shamelessly exploiting and mocking our sacred religious traditions.... These sacred ways have enabled our people to survive five centuries of genocide. We will not allow these most sacred gifts to be desecrated and abused.... OUR SACRED SPIRITUAL PRACTICES ARE NOT FOR SALE, AND IF YOU TRY TO STEAL THEM FROM US, YOU ARE GUILTY OF SPIRITUAL GENOCIDE."[1]

The flyer distributed at Storm's San Francisco lecture was accompanied by a document titled "American Indian International Tribunal Elder’s Statement" that concluded with "Our young people are getting restless. They have said they will take care of those who are abusing our ceremonies and sacred objects in their own way."[1]

The Colorado chapter of the American Indian Movement confronted Sun Bear during one of his $500/head weekend-long "spiritual retreat".[16]

Lakota leader Rick Williams has criticized Sun Bear's eclectic use of combined elements from different tribes, saying it creates a dangerous spiritual imbalance. He argues that every part of different Indigenous cultures' traditions serves a specific purpose, and that mixing elements between cultures will not only lead to the purposes being distorted and lost, but can potentially endanger the practitioner.[10]

Anthropologist Alice Keheo writes that Native medicine wheel rites, along with other Indigenous observance of the cyclical patterns in nature and life, are one of the reasons Natives are stereotyped as more spiritual than non-Natives.[3]: 195–196

Distortions of Indigenous culture, and thus identity, using things like Storm and LaDuke's medicine wheel, is criticized as 'killing off' real Indigenous cultures and displacing them by fictional Indigenous identities and cultures. The denial of agency in dismissing the concerns, wishes, and traditional cultures of Indigenous people through popularizing such works as Seven Arrows is criticized as continuing the indignity of desecrating, mocking and abusing Indigenous traditional ceremonies and spiritual practices.[12]

Ironically, as Bear Nicholas notes, objections and criticism about the medicine wheel symbol as a dangerous and false invented tradition are now condemned by many as disrespectful to tradition.[4]

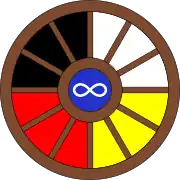

Variations

Among users of the medicine wheel symbol, variations exist. The axes of the medicine wheel might also be rotated to be vertical. The quadrants can be rotated into a different arrangement and the order of the colours can be different, depending on the community. Meanings and associations with the colours also vary between nations.[43] Some Anishinaabe communities add a circle in the centre, often coloured green, to represent balance.[44][45][46] The black quadrant is often replaced with a blue quadrant in some Cree and Ojibwe communities.[47][48] Métis occasionally add a circle with the Métis flag or a green circle in the centre or use the symbol of a Red River cart wheel overlaid on the medicine wheel.[49][50][51] Some versions of the medicine wheel consist of a hoop with two perpendicular axes connected to the hoop, and half of each axes and a connected quadrant of the hoop are coloured with the centre often left uncoloured.[52][53][54] Some Christian groups have incorporated the Christian cross into the medicine wheel in a manner similar to the Celtic cross.[55] In addition to the variations between Indigenous nations, there are also variations used within Indigenous nations, and not all Indigenous nations have adopted the medicine wheel, so care must be taken to not generalize.[56]

Gallery

These examples are not a definitive list of medicine wheel designs and this is not an exhaustive list of the variations that exist. Variations exist between and within Indigenous nations, and no one design represents all Indigenous nations. These are provided as examples only.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shaw, Christopher (August 1995). "A Theft of Spirit?". New Age Journal. pp. 84–92. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jenkins, Philip (21 September 2004). Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195347654. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Kehoe, Alice B (1990). "Primal Gaia: Primitivists and Plastic Medicine Men". In Clifton, James A (ed.). The Invented Indian Cultural Fictions and Government Policies. New Brunswick NJ: The Transaction Publishers. pp. 193–209. ISBN 9781560007456. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bear Nicholas, Andrea (April 2008). "The Assault on Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Past and Present". In Hulan, Renée; Eigenbrod, Renate (eds.). Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Theory, Practice, Ethics. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Pub Co Ltd. pp. 7–43. ISBN 9781552662670.

- 1 2 Thomason, Timothy C (27 October 2013). "The Medicine Wheel as a Symbol of Native American Psychology". The Jung Page. The Jung Center of Houston. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ Chavers, Dean (15 October 2014). "5 Fake Indians: Checking a Box Doesn't Make You Native". Ict News. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- 1 2 Beyer, Steve (3 February 2008). "Selling Spirituality". Singing to the Plants. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird (1972). "Massaum Ceremony". The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways. Vol. 2: War, Ceremonies, and Religion (Bison Book ed.). Lincoln NB: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 285–337. ISBN 9780803257726. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ Powell, Peter J (1998). Sweet Medicine: The Continuing Role of the Sacred Arrows, the Sun Dance, and the Sacred Buffalo Hat in Northern Cheyenne History. Vol. 1. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806130286. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Churchill, Ward (21 September 2004). "Spiritual Hucksterism: The rise of the plastic medicine men". In Harvey, Graham (ed.). Shamanism: A Reader. London UK: Psychology Press. pp. 324–329. ISBN 9780415253291. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 Parkhill, Thomas C (1997). Weaving Ourselves into the Land: Charles Godfrey Leland, "Indians" and the Study of Native American Religions. Albany NY: State University of New York Press. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- 1 2 Skidmore, Kyle P (25 June 2017). "Stealing Wisdom: Cultural Appropriation and Misrepresentation within Adventure Therapy and Outdoor Education". OutdoorEd.com. Outdoor Ed LLC. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Costo, Rupert (1972). "Seven Arrows Desecrates Cheyenne". The Indian Historian. 5 (2): 441–442.

- 1 2 Brumble III, H David (1983). "Indian Sacred Materials: Kroeber, Kroeber, Waters, and Momaday". In Swann, Brian (ed.). Smoothing the Ground: Essays on Native American Oral Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 283–300. ISBN 9780520049130. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Jaeger, Lowell (1980). "Seven Arrows: Seven Years After". Studies in American Indian Literatures. Association for the Study of American Indian Literatures. 4 (2): 16–19. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- 1 2 Aldred, Lisa (2000). "Plastic Shamans and Astroturf Sun Dances: New Age Commercialization of Native American Spirituality". The American Indian Quarterly. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 24 (3): 329–352. doi:10.1353/aiq.2000.0001. PMID 17086676. S2CID 6012903. ProQuest 216857927. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ Kakar, Sudhir (1991). Shamans, mystics and doctors: a psychological inquiry into India and its healing traditions. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226422794. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand (2010). History of Western Philosophy (Repr ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415325059. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Cordova, Viola F (2002). "Bounded Space: The Four Directions" (PDF). Newsletter on American Indians in Philosophy. University of Delaware: American Philosophical Association. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Cordova, Viola F (2007). Moore, Kathleen Dean; Peters, Kurt; Jojola, Ted; Lacy, Amber (eds.). How it is: the native American philosophy of V.F. Cordova. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816526499.

- 1 2 Moore, John H (1996). The Cheyenne. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers Inc. ISBN 9781557864840. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore, John H (August 1973). "Book Review: Seven Arrow. Hyemeyohsts Storm". American Anthropologist. 75 (4): 1040–1042. doi:10.1525/aa.1973.75.4.02a00810.

- ↑ Anderson, Jeffrey (8 May 2018). "Arapaho". Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Nahwegahbow, Barb (21 November 2017). "The Anishinawbe way of life depicted in paintings". Anishinabek News. Union of Ontario Indians. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Rice, John. "The Miikaans Teachings". Wise Teachings. Feather Carriers. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Preston, Richard J (1982). "Towards a General Statement on the Eastern Cree Structure of Knowledge". In Cowan, William (ed.). Papers of the Thirteenth Algonquian Conference: was held October 23 - 25, 1981 at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education in Toronto. Ottawa: Carleton University. pp. 299–306. ISBN 9780770901233.

- ↑ von Linné, Carl (1767). "Mammalia, Primates, Homo.". Caroli a Linné ... Systema naturae,: per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (13 ed.). Typis Ioannis Thomae. p. 29. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Davis, Bret W (2 October 2015). The Life of the Body-Heart-Mind-Spirit: Cross-Cultural Reflections on Cura Personalis (Speech). Nachbahr Award Talk. Loyola University Maryland: Loyola University Maryland. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Proverbs, Tracey A; Stewart, Abraham R; Vittrekwa, Alice; Vittrekwa, Ernest; Hovel, Rachel A; Hodgson, Emma E (27 November 2020). "Disrupted ecosystem and human phenology at the climate frontline in Gwich'in First Nation territory". Conservation Biology. 35 (4): 1348–1352. doi:10.1111/cobi.13672. PMC 8411416. PMID 33245587.

- ↑ "Learn the five seasons of the Ojibwe calendar". WWF-Canada. World Wildlife Federation. 11 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 Hodge, Frederick Webb (1913). "Appendix to the Tenth Report of the Geographic Board of Canada". In White, James (ed.). Handbooks of Indians of Canada. Ottawa: C. H. Parmelee. pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies (29 April 2021). "Calendars Then and Now". Lakota Times. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Johnson, Duane (2008). "The Six Seasons of the Woodland Cree: A Lesson to Support Science 10". Stewart Resources Centre. Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Glass, Justine (1965). Witchcraft, the Sixth Sense—and Us. London: Neville Spearman. p. 98.

- ↑ Goulet, Keith (2008). Brownstone, Arni (ed.). "Animate and inanimate: The Cree Nehinuw view". Material Histories: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Marischal Museum. Aberdeen, UK: University of Aberdeen: 7–19.

- ↑ Napoleon, Art (2014). Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview (MA). University of Victoria. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Andrus, Cecil D (August 1979). American Indian Religious Freedom Act (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare. p. 68. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Farrell, Lindsay L; Johnson, Cheyenne; Lavalley, Jennifer; Pooni, Neesha; Chase, Corrina; Wieman, Cornelia (March 2020). Indigenous Anti-racism and Anti-colonial (ARC) Framework (PDF) (Report). British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ↑ "Saskatchewan RCMP flies the Métis Nation flag on Louis Riel Day in Regina, Saskatoon and Prince Albert". Saskatchewan, Canada: Royal Canadian Mounted Police. 16 November 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 Storm, Hyemeyohsts (1997). Lightningbolt. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345361424.

- 1 2 3 Storm, Hyemeyohsts (1972). Seven Arrows. New York, NY: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780345329011.

- ↑ McClinton-Temple, Jennifer; Velie, Alan (12 May 2010). Encyclopedia of American Indian Literature. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 346. ISBN 9781438120874. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ↑ Joseph, Bob. "What is an Indigenous Medicine Wheel?". Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ McGurry, Renée. "The Anishinaabek Medicine Wheel". Government of Treaty 2 Territory. First Nations in Treaty 2 Territory. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "The power of traditional ways". KBIC Health Systems. Keweenaw Bay Dept. Of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Lyons, Michael; Holtan, Heidi. "Boozhoo Nanaboozhoo Ojibwe word of the day is Medicine Wheel "Mashkikii Detibised"". KAXE. KAXE/KBXE. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Whiskeyjack, Francis. "The Medicine Wheel". Windspeaker.com. Aboriginal Multi-Media Society. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "Medicine Wheel Native American Teachings Explained?". Powwow Times. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "Land Acknowledgement". Office of the Vice-Provost Indigenous Engagement. University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Bellegarde, Brad (9 January 2018). "Métis educator sets up tent in classroom to share his grandparents' experience with students". CBC News. CBC. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Your Guide to Help You Understand Cancer & Heal/Toon Liivr chi Nishitoohtamnun li Kaansayr (PDF). Saskatoon SK: Métis Nation—Saskatchewan. 2023. p. 58. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ "The Medicine Wheel Talking Circle Training Model". Native American Coalition. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "Medicine wheel". National Museum of the American Indian. Smithsonian. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "The Medicine Wheel". National Park Service. National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ "The Medicine Wheel". Dayspring NAUMC. Dayspring Native American United Methodist Church. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ Douglas, Vasiliki (28 June 2013). "2 – Western and Aboriginal Ways of Knowing". Introduction to Aboriginal Health and Health Care in Canada: Bridging Health and Healing. New York, NY, USA: Springer Publishing Company. p. 30. ISBN 9780826117991. Retrieved 12 May 2023.