| History of art |

|---|

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, with over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, genres, revivals, the artists' crafts, and the artists themselves.

Art historians attempt to classify medieval art into major periods and styles, often with some difficulty. A generally accepted scheme includes the later phases of Early Christian art, Migration Period art, Byzantine art, Insular art, Pre-Romanesque, Romanesque art, and Gothic art, as well as many other periods within these central styles. In addition, each region, mostly during the period in the process of becoming nations or cultures, had its own distinct artistic style, such as Anglo-Saxon art or Viking art.

Medieval art was produced in many media, and works survive in large numbers in sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, metalwork and mosaics, all of which have had a higher survival rate than other media such as fresco wall-paintings, work in precious metals or textiles, including tapestry. Especially in the early part of the period, works in the so-called "minor arts" or decorative arts, such as metalwork, ivory carving, vitreous enamel and embroidery using precious metals, were probably more highly valued than paintings or monumental sculpture.[1]

Medieval art in Europe grew out of the artistic heritage of the Roman Empire and the iconographic traditions of the early Christian church. These sources were mixed with the vigorous "barbarian" artistic culture of Northern Europe to produce a remarkable artistic legacy. Indeed, the history of medieval art can be seen as the history of the interplay between the elements of classical, early Christian and "barbarian" art.[2] Apart from the formal aspects of classicism, there was a continuous tradition of realistic depiction of objects that survived in Byzantine art throughout the period, while in the West it appears intermittently, combining and sometimes competing with new expressionist possibilities developed in Western Europe and the Northern legacy of energetic decorative elements. The period ended with the self-perceived Renaissance recovery of the skills and values of classical art, and the artistic legacy of the Middle Ages was then disparaged for some centuries. Since a revival of interest and understanding in the 19th century it has been seen as a period of enormous achievement that underlies the development of later Western art.

Overview

The first several centuries of the Middle Ages in Europe — up to about 800 AD - saw a decrease in prosperity, stability, and population, followed by a fairly steady and general increase until the massive setback of the Black Death around 1350, which is estimated to have killed at least a third of the overall population in Europe, with generally higher rates in the south and lower in the north. Many regions did not regain their former population levels until the 17th century. The population of Europe is estimated to have reached a low point of about 18 million in 650, to have doubled around the year 1000, and to have reached over 70 million by 1340, just before the Black Death. In 1450 it was still only 50 million. To these figures, Northern Europe, especially Britain, contributed a lower proportion than today, and Southern Europe, including France, a higher one.[3] The increase in prosperity, for those who survived, was much less affected by the Black Death. Until about the 11th century most of Europe was short of agricultural labour, with large amounts of unused land, and the Medieval Warm Period benefited agriculture until about 1315.[4]

The medieval period eventually saw the falling away of the invasions and incursions from outside the area that characterized the first millennium. The Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries suddenly and permanently removed all of North Africa from the Western world, and over the rest of the period Islamic peoples gradually took over the Byzantine Empire, until the end of the Middle Ages when Catholic Europe, having regained the Iberian peninsula in the southwest, was once again under Muslim threat from the southeast.

At the start of the medieval period most significant works of art were very rare and costly objects associated with secular elites, monasteries or major churches and, if religious, largely produced by monks. By the end of the Middle Ages works of considerable artistic interest could be found in small villages and significant numbers of bourgeois homes in towns, and their production was in many places an important local industry, with artists from the clergy now the exception. However the Rule of St Benedict permitted the sale of works of art by monasteries, and it is clear that throughout the period monks might produce art, including secular works, commercially for a lay market, and monasteries would equally hire lay specialists where necessary.[5]

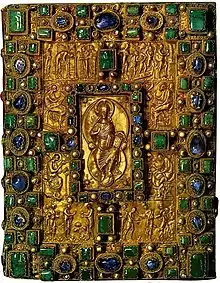

The impression may be left by the surviving works that almost all medieval art was religious. This is far from the case; though the church became very wealthy over the Middle Ages and was prepared at times to spend lavishly on art, there was also much secular art of equivalent quality which has suffered from a far higher rate of wear and tear, loss and destruction. The Middle Ages generally lacked the concept of preserving older works for their artistic merit, as opposed to their association with a saint or founder figure, and the following periods of the Renaissance and Baroque tended to disparage medieval art. Most luxury illuminated manuscripts of the Early Middle Ages had lavish treasure binding book-covers in precious metal, ivory and jewels; the re-bound pages and ivory reliefs for the covers have survived in far greater numbers than complete covers, which have mostly been stripped off for their valuable materials at some point.

Most churches have been rebuilt, often several times, but medieval palaces and large houses have been lost at a far greater rate, which is also true of their fittings and decoration. In England, churches survive largely intact from every century since the 7th, and in considerable numbers for the later ones—the city of Norwich alone has 40 medieval churches—but of the dozens of royal palaces none survive from earlier than the 11th century, and only a handful of remnants from the rest of the period.[6] The situation is similar in most of Europe, though the 14th century Palais des Papes in Avignon survives largely intact. Many of the longest running scholarly disputes over the date and origin of individual works relate to secular pieces, because they are so much rarer - the Anglo-Saxon Fuller Brooch was refused by the British Museum as an implausible fake, and small free-standing secular bronze sculptures are so rare that the date, origin and even authenticity of both of the two best examples has been argued over for decades.[7]

The use of valuable materials is a constant in medieval art; until the end of the period, far more was typically spent on buying them than on paying the artists, even if these were not monks performing their duties. Gold was used for objects for churches and palaces, personal jewellery and the fittings of clothes, and—fixed to the back of glass tesserae—as a solid background for mosaics, or applied as gold leaf to miniatures in manuscripts and panel paintings. Many objects using precious metals were made in the knowledge that their bullion value might be realized at a future point—only near the end of the period could money be invested other than in real estate, except at great risk or by committing usury.

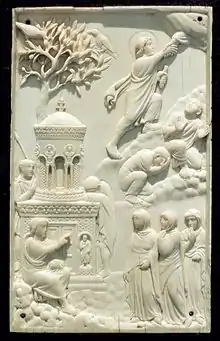

The even more expensive pigment ultramarine, made from ground lapis lazuli obtainable only from Afghanistan, was used lavishly in the Gothic period, more often for the traditional blue outer mantle of the Virgin Mary than for skies. Ivory, often painted, was an important material until the very end of the period, well illustrating the shift in luxury art to secular works; at the beginning of the period most uses were shifting from consular diptychs to religious objects such as book-covers, reliquaries and croziers, but in the Gothic period secular mirror-cases, caskets and decorated combs become common among the well-off. As thin ivory panels carved in relief could rarely be recycled for another work, the number of survivals is relatively high—the same is true of manuscript pages, although these were often re-cycled by scraping, whereupon they become palimpsests.

Even these basic materials were costly: when the Anglo-Saxon Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey planned to create three copies of the bible in 692—of which one survives as the Codex Amiatinus—the first step necessary was to plan to breed the cattle to supply the 1,600 calves to give the skin for the vellum required.[8]

Paper became available in the last centuries of the period, but was also extremely expensive by today's standards; woodcuts sold to ordinary pilgrims at shrines were often matchbook size or smaller. Modern dendrochronology has revealed that most of the oak for panels used in Early Netherlandish painting of the 15th century was felled in the Vistula basin in Poland, from where it was shipped down the river and across the Baltic and North Seas to Flemish ports, before being seasoned for several years.[9]

Art in the Middle Ages is a broad subject and art historians traditionally divide it in several large-scale phases, styles or periods. The period of the Middle Ages neither begins nor ends neatly at any particular date, nor at the same time in all regions, and the same is true for the major phases of art within the period.[10] The major phases are covered in the following sections.

Early Christian and Late Antique art

_-_tondo_lato_settentrionale_destro.jpg.webp)

Early Christian art, more generally described as Late Antique art, covers the period from about 200 (before which no distinct Christian art survives), until the onset of a fully Byzantine style in about 500. There continue to be different views as to when the medieval period begins during this time, both in terms of general history and specifically art history, but it is most often placed late in the period. In the course of the 4th century Christianity went from being a persecuted popular sect to the official religion of the Empire, adapting existing Roman styles and often iconography, from both popular and Imperial art. From the start of the period the main survivals of Christian art are the tomb-paintings in popular styles of the catacombs of Rome, but by the end there were a number of lavish mosaics in churches built under Imperial patronage.

Over this period imperial Late Roman art went through a strikingly "baroque" phase, and then largely abandoned classical style and Greek realism in favour of a more mystical and hieratic style—a process that was well underway before Christianity became a major influence on imperial art. Influences from Eastern parts of the Empire—Egypt, Syria and beyond, and also a robust "Italic" vernacular tradition, contributed to this process.

Figures are mostly seen frontally staring out at the viewer, where classical art tended to show a profile view - the change was eventually seen even on coins. The individuality of portraits, a great strength of Roman art, declines sharply, and the anatomy and drapery of figures is shown with much less realism. The models from which medieval Northern Europe in particular formed its idea of "Roman" style were nearly all portable Late Antique works, and the Late Antique carved sarcophagi found all over the former Roman Empire;[11] the determination to find earlier "purer" classical models, was a key element in the art all'antica of the Renaissance.[12]

Ivory reliefs

Ascension of Christ and Noli me tangere, c. 400, with many elements of classical style remaining. See Drogo Sacramentary for a similar Ascension 450 years later.

Ascension of Christ and Noli me tangere, c. 400, with many elements of classical style remaining. See Drogo Sacramentary for a similar Ascension 450 years later..jpg.webp) Consular diptych, Constantinople 506, in fully Late Antique style

Consular diptych, Constantinople 506, in fully Late Antique style Ottonian panel from the Magdeburg Ivories, in a bold monumental style with little attempt at classicism; Milan 962–973.

Ottonian panel from the Magdeburg Ivories, in a bold monumental style with little attempt at classicism; Milan 962–973. Late 14th century French Gothic triptych, probably for a lay owner, with scenes from the Life of the Virgin

Late 14th century French Gothic triptych, probably for a lay owner, with scenes from the Life of the Virgin

Byzantine art

Byzantine art is the art of the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire formed after the division of the Roman Empire between Eastern and Western halves, and sometimes of parts of Italy under Byzantine rule. It emerges from Late Antiquity in about 500 CE and soon formed a tradition distinct from that of Catholic Europe but with great influence over it. In the early medieval period the best Byzantine art, often from the large Imperial workshops, represented an ideal of sophistication and technique which European patrons tried to emulate. During the period of Byzantine iconoclasm in 730-843 the vast majority of icons (sacred images usually painted on wood) were destroyed; so little remains that today any discovery sheds new understanding, and most remaining works are in Italy (Rome and Ravenna etc.), or Egypt at Saint Catherine's Monastery.

Byzantine art was extremely conservative, for religious and cultural reasons, but retained a continuous tradition of Greek realism, which contended with a strong anti-realist and hieratic impulse. After the resumption of icon production in 843 until 1453 the Byzantine art tradition continued with relatively few changes, despite, or because of, the slow decline of the Empire. There was a notable revival of classical style in works of 10th century court art like the Paris Psalter, and throughout the period manuscript illumination shows parallel styles, often used by the same artist, for iconic figures in framed miniatures and more informal small scenes or figures added unframed in the margins of the text in a much more realist style.[13]

Monumental sculpture with figures remained a taboo in Byzantine art; hardly any exceptions are known. But small ivory reliefs, almost all in the iconic mode (the Harbaville Triptych is of similar date to the Paris Psalter, but very different in style), were a speciality, as was relief decoration on bowls and other metal objects.

The Byzantine Empire produced much of the finest art of the Middle Ages in terms of quality of material and workmanship, with court production centred on Constantinople, although some art historians have questioned the assumption, still commonly made, that all work of the best quality with no indication as to origin was produced in the capital. Byzantine art's crowning achievement were the monumental frescos and mosaics inside domed churches, most of which have not survived due to natural disasters and the appropriation of churches to mosques.

Byzantine art exercised a continuous trickle of influence on Western European art, and the splendours of the Byzantine court and monasteries, even at the end of the Empire, provided a model for Western rulers and secular and clerical patrons. For example, Byzantine silk textiles, often woven or embroidered with designs of both animal and human figures, the former often reflecting traditions originating much further east, were unexcelled in the Christian world until almost the end of the Empire. These were produced, but probably not entirely so, in Imperial workshops in Constantinople, about whose operations we know next to nothing—similar workshops are often conjectured for other arts, with even less evidence. The gold ground style in mosaics, icons and manuscript miniatures was common across europe by the Gothic period. Some other decorative arts were less developed; Byzantine ceramics rarely rise above the level of attractive folk art, despite the Ancient Greek heritage and the impressive future in the Ottoman period of İznik wares and other types of pottery.

The Coptic art of Egypt took a different path; after the Coptic Church separated in the mid-5th century it was never again supported by the state, and native Egyptian influences dominated to produce a completely non-realist and somewhat naive style of large-eyed figures floating in blank space. This was capable of great expressiveness, and took the "Eastern" component of Byzantine art to its logical conclusions. Coptic decoration used intricate geometric designs, often anticipating Islamic art. Because of the exceptionally good preservation of Egyptian burials, we know more about the textiles used by the less well-off in Egypt than anywhere else. These were often elaborately decorated with figurative and patterned designs. Other local traditions in Armenia, Syria, Georgia and elsewhere showed generally less sophistication, but often more vigour than the art of Constantinople, and sometimes, especially in architecture, seem to have had influence even in Western Europe. For example, figurative monumental sculpture on the outside of churches appears here some centuries before it is seen in the West.[14]

Migration Period through Christianization

Migration Period art describes the art of the "barbarian" Germanic and Eastern-European peoples who were on the move, and then settling within the former Roman Empire, during the Migration Period from about 300-700; the blanket term covers a wide range of ethnic or regional styles including early Anglo-Saxon art, Visigothic art, Viking art, and Merovingian art, all of which made use of the animal style as well as geometric motifs derived from classical art. By this period the animal style had reached a much more abstracted form than in earlier Scythian art or La Tène style. Most artworks were small and portable and those surviving are mostly jewellery and metalwork, with the art expressed in geometric or schematic designs, often beautifully conceived and made, with few human figures and no attempt at realism. The early Anglo-Saxon grave goods from Sutton Hoo are among the best examples.

As the "barbarian" peoples were Christianized, these influences interacted with the post-classical Mediterranean Christian artistic tradition, and new forms like the illuminated manuscript,[15] and indeed coins, which attempted to emulate Roman provincial coins and Byzantine types. Early coinage like the sceat shows designers completely unused to depicting a head in profile grappling with the problem in a variety of different ways.

As for larger works, there are references to Anglo-Saxon wooden pagan statues, all now lost, and in Norse art the tradition of carved runestones was maintained after their conversion to Christianity. The Celtic Picts of Scotland also carved stones before and after conversion, and the distinctive Anglo-Saxon and Irish tradition of large outdoor carved crosses may reflect earlier pagan works. Viking art from later centuries in Scandinavia and parts of the British Isles includes work from both pagan and Christian backgrounds, and was one of the last flowerings of this broad group of styles.

Parts of a Norwegian wooden doorway, 12th century, in the Urnes style

Parts of a Norwegian wooden doorway, 12th century, in the Urnes style.JPG.webp) Image-stone from Sweden

Image-stone from Sweden

Insular art

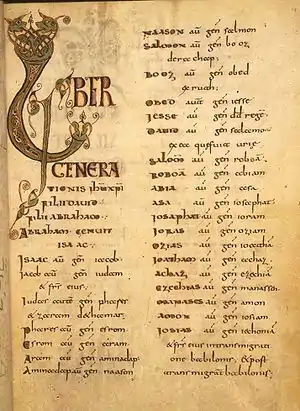

Insular art refers to the distinct style found in Ireland and Britain from about the 7th century, to about the 10th century, lasting later in Ireland, and parts of Scotland. The style saw a fusion between the traditions of Celtic art, the Germanic Migration period art of the Anglo-Saxons and the Christian forms of the book, high crosses and liturgical metalwork.

Extremely detailed geometric, interlace, and stylised animal decoration, with forms derived from secular metalwork like brooches, spread boldly across manuscripts, usually gospel books like the Book of Kells, with whole carpet pages devoted to such designs, and the development of the large decorated and historiated initial. There were very few human figures—most often these were Evangelist portraits—and these were crude, even when closely following Late Antique models.

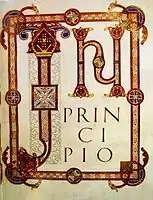

The insular manuscript style was transmitted to the continent by the Hiberno-Scottish mission, and its anti-classical energy was extremely important in the formation of later medieval styles. In most Late Antique manuscripts text and decoration were kept clearly apart, though some initials began to be enlarged and elaborated, but major insular manuscripts sometimes take a whole page for a single initial or the first few words (see illustration) at beginnings of gospels or other sections in a book. Allowing decoration a "right to roam" was to be very influential on Romanesque and Gothic art in all media.

The buildings of the monasteries for which the insular gospel books were made were then small and could fairly be called primitive, especially in Ireland. There increasingly were other decorations to churches, where possible in precious metals, and a handful of these survive, like the Ardagh Chalice, together with a larger number of extremely ornate and finely made pieces of secular high-status jewellery, the Celtic brooches probably worn mainly by men, of which the Tara Brooch is the most spectacular.

"Franco-Saxon" is a term for a school of late Carolingian illumination in north-eastern France that used insular-style decoration, including super-large initials, sometimes in combination with figurative images typical of contemporary French styles. The "most tenacious of all the Carolingian styles", it continued until as late as the 11th century.[16]

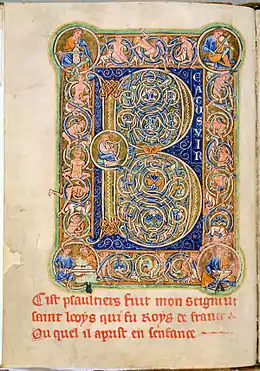

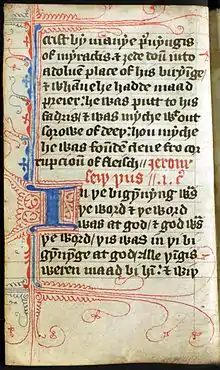

Giant initials

Carolingian version of Insular style—compare the "Liber generationis ..." above.

Carolingian version of Insular style—compare the "Liber generationis ..." above. Franco-Saxon "In principio", 871-3.

Franco-Saxon "In principio", 871-3. Romanesque interlace, "inhabited" with figures, England, 1190–1200.

Romanesque interlace, "inhabited" with figures, England, 1190–1200. Typical Gothic pen flourishes in an unillustrated working copy of John's gospel in English, late 14th century.

Typical Gothic pen flourishes in an unillustrated working copy of John's gospel in English, late 14th century.

The influence of Islamic art

Islamic art during the Middle Ages falls outside the scope of this article, but it was widely imported and admired by European elites, and its influence needs mention.[17] Islamic art covers a wide variety of media including calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts, textiles, ceramics, metalwork and glass, and refers to the art of Muslim countries in the Near East, Islamic Spain, and Northern Africa, though by no means always Muslim artists or craftsmen. Glass production, for example, remained a Jewish speciality throughout the period, and Christian art, as in Coptic Egypt continued, especially during the earlier centuries, keeping some contacts with Europe. There was an early formative stage from 600-900 and the development of regional styles from 900 onwards. Early Islamic art used mosaic artists and sculptors trained in the Byzantine and Coptic traditions.[18] Instead of wall-paintings, Islamic art used painted tiles, from as early as 862-3 (at the Great Mosque of Kairouan in modern Tunisia), which also spread to Europe.[19] According to John Ruskin, the Doge's Palace in Venice contains "three elements in exactly equal proportions — the Roman, the Lombard, and Arab. It is the central building of the world. ... the history of Gothic architecture is the history of the refinement and spiritualisation of Northern work under its influence".[20]

Islamic rulers controlled at various points parts of Southern Italy and most of modern Spain and Portugal, as well as the Balkans, all of which retained large Christian populations. The Christian Crusaders equally ruled Islamic populations. Crusader art is mainly a hybrid of Catholic and Byzantine styles, with little Islamic influence, but the Mozarabic art of Christians in Al Andaluz seems to show considerable influence from Islamic art, though the results are little like contemporary Islamic works. Islamic influence can also be traced in the mainstream of Western medieval art, for example in the Romanesque portal at Moissac in southern France, where it shows in both decorative elements, like the scalloped edges to the doorway, the circular decorations on the lintel above, and also in having Christ in Majesty surrounded by musicians, which was to become a common feature of Western heavenly scenes, and probably derives from images of Islamic kings on their diwan.[21] Calligraphy, ornament and the decorative arts generally were more important than in the West.[22]

The Hispano-Moresque pottery wares of Spain were first produced in Al-Andaluz, but Muslim potters then seem to have emigrated to the area of Christian Valencia, where they produced work that was exported to Christian elites across Europe;[23] other types of Islamic luxury goods, notably silk textiles and carpets, came from the generally wealthier[24] eastern Islamic world itself (the Islamic conduits to Europe west of the Nile were, however, not wealthier),[25] with many passing through Venice.[26] However, for the most part luxury products of the court culture such as silks, ivory, precious stones and jewels were imported to Europe only in an unfinished form and manufactured into the end product labelled as "eastern" by local medieval artisans.[27] They were free from depictions of religious scenes and normally decorated with ornament, which made them easy to accept in the West,[28] indeed by the late Middle Ages there was a fashion for pseudo-Kufic imitations of Arabic script used decoratively in Western art.

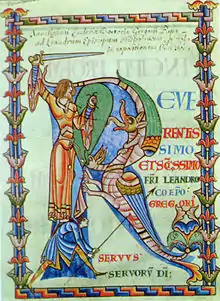

Pre-Romanesque art

Pre-Romanesque is a term for architecture and to some extent pictorial and portable art found initially in Southern Europe (Spain, Italy and Southern France) between the Late Antique period to the start of the Romanesque period in the 11th century. Northern European art gradually forms part of the movement after Christianization as it assimilates post-classical styles. The Carolingian art of the Frankish Empire, especially modern France and Germany, from roughly 780-900 takes its name from Charlemagne and is an art of the court circle and a few monastic centres under Imperial patronage, that consciously sought to revive "Roman" styles and standards as befitted the new Empire of the West. Some centres of Carolingian production also pioneered expressive styles in works like the Utrecht Psalter and Ebbo Gospels. Christian monumental sculpture is recorded for the first time, and depiction of the human figure in narrative scenes became confident for the first time in Northern art. Carolingian architecture produced larger buildings than had been seen since Roman times, and the westwork and other innovations.[29]

After the collapse of the dynasty there was a hiatus before a new dynasty brought a revival in Germany with Ottonian art, again centred on the court and monasteries, with art that moved towards great expressiveness through simple forms that achieve monumentality even in small works like ivory reliefs and manuscript miniatures, above all those of the Reichenau School, such as the Pericopes of Henry II (1002–1012). Later Anglo-Saxon art in England, from about 900, was expressive in a very different way, with agitated figures and even drapery perhaps best shown in the many pen drawings in manuscripts. The Mozarabic art of Christian Spain had strong Islamic influence, and a complete lack of interest in realism in its brilliantly coloured miniatures, where figures are presented as entirely flat patterns. Both of these were to influence the formation in France of the Romanesque style.[30]

Carolingian Evangelist portrait from the Codex Aureus of Lorsch, using a Late Antique model, late 8th century

Carolingian Evangelist portrait from the Codex Aureus of Lorsch, using a Late Antique model, late 8th century Another Carolingian evangelist portrait in Greek/Byzantine realist style, probably by a Greek artist, also late 8th century.[31]

Another Carolingian evangelist portrait in Greek/Byzantine realist style, probably by a Greek artist, also late 8th century.[31] Mozarabic Beatus miniature, late 10th century.

Mozarabic Beatus miniature, late 10th century. The Bamberg Apocalypse, from the Ottonian Reichenau School, achieves monumentality in a small scale. 1000–1020.

The Bamberg Apocalypse, from the Ottonian Reichenau School, achieves monumentality in a small scale. 1000–1020.

Romanesque art

Romanesque art developed in the period between about 1000 to the rise of Gothic art in the 12th century, in conjunction with the rise of monasticism in Western Europe. The style developed initially in France, but spread to Christian Spain, England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, and elsewhere to become the first medieval style found all over Europe, though with regional differences.[32] The arrival of the style coincided with a great increase in church-building, and in the size of cathedrals and larger churches; many of these were rebuilt in subsequent periods, but often reached roughly their present size in the Romanesque period. Romanesque architecture is dominated by thick walls, massive structures conceived as a single organic form, with vaulted roofs and round-headed windows and arches.

Figurative sculpture, originally colourfully painted, plays an integral and important part in these buildings, in the capitals of columns, as well as around impressive portals, usually centred on a tympanum above the main doors, as at Vézelay Abbey and Autun Cathedral. Reliefs are much more common than free-standing statues in stone, but Romanesque relief became much higher, with some elements fully detached from the wall behind. Large carvings also became important, especially painted wooden crucifixes like the Gero Cross from the very start of the period, and figures of the Virgin Mary like the Golden Madonna of Essen. Royalty and the higher clergy began to commission life-size effigies for tomb monuments. Some churches had massive pairs of bronze doors decorated with narrative relief panels, like the Gniezno Doors or those at Hildesheim, "the first decorated bronze doors cast in one piece in the West since Roman times", and arguably the finest before the Renaissance.[33]

.jpg.webp)

Most churches were extensively frescoed; a typical scheme had Christ in Majesty at the east (altar) end, a Last Judgement at the west end over the doors, and scenes from the Life of Christ facing typologically matching Old Testament scenes on the nave walls. The "greatest surviving monument of Romanesque wall painting", much reduced from what was originally there, is in the Abbey Church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe near Poitiers, where the rounded barrel vault of the nave, the crypt, portico and other areas retain most of their paintings.[34] An equivalent cycle in Sant'Angelo in Formis at Capua in southern Italy by Italian painters trained by Greeks illustrates the continuing predominance of Byzantine style in much of Italy.[35]

Romanesque sculpture and painting is often vigorous and expressive, and inventive in terms of iconography—the subjects chosen and their treatment. Though many features absorbed from classical art form part of the Romanesque style, Romanesque artists rarely intended to achieve any sort of classical effect, except perhaps in Mosan art.[36] As art became seen by a wider section of the population, and because of challenges from new heresies, art became more didactic, and the local church the "Poor Man's Bible". At the same time grotesque beasts and monsters, and fights with or between them, were popular themes, to which religious meanings might be loosely attached, although this did not impress St Bernard of Clairvaux, who famously denounced such distractions in monasteries:

But in the cloister, in the sight of the reading monks, what is the point of such ridiculous monstrosity, the strange kind of shapely shapelessness? Why these unsightly monkeys, why these fierce lions, why the monstrous centaurs, why semi-humans, why spotted tigers, why fighting soldiers, why trumpeting huntsmen? ... In short there is such a variety and such a diversity of strange shapes everywhere that we may prefer to read the marbles rather than the books.[37]

He might well have known the miniature at left, which was produced at Cîteaux Abbey before the young Bernard was transferred from there in 1115.[38]

During the period typology became the dominant approach in theological literature and art to interpreting the bible, with Old Testament incidents seen as pre-figurations of aspects of the life of Christ, and shown paired with their corresponding New Testament episode. Often the iconography of the New Testament scene was based on traditions and models originating in Late Antiquity, but the iconography of the Old Testament episode had to be invented in this period, for lack of precedents. New themes such as the Tree of Jesse were devised, and representations of God the Father became more acceptable. The vast majority of surviving art is religious. Mosan art was an especially refined regional style, with much superb metalwork surviving, often combined with enamel, and elements of classicism rare in Romanesque art, as in the Baptismal font at St Bartholomew's Church, Liège, or the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne, one of a number of surviving works by Nicholas of Verdun, whose services were sought across north-western Europe.

Stained glass became a significant art-form in the period, though little Romanesque glass survives. In illuminated manuscripts the bible became a new focus of intensive decoration, with the psalter also remaining important. The strong emphasis on the suffering of Christ and other sacred figures entered Western art in this period, a feature that strongly distinguishes it from both Byzantine and classical art for the remainder of the Middle Ages and beyond. The Gero Cross of 965-970, at the cusp of Ottonian and Romanesque art, has been called the first work to exhibit this.[39] The end of the Romanesque period saw the start of the greatly increased emphasis on the Virgin Mary in theology, literature and so also art that was to reach its full extent in the Gothic period.

The 12th-century frescos in St Botolph's Church, England, are part of the 'Lewes Group' of Romanesque paintings created for Lewes Priory.[40]

The 12th-century frescos in St Botolph's Church, England, are part of the 'Lewes Group' of Romanesque paintings created for Lewes Priory.[40]

Gothic art

Gothic art is a variable term depending on the craft, place and time. The term originated with the Gothic architecture which developed in France from about 1137 with the rebuilding of the Abbey Church of St Denis. As with Romanesque architecture, this included sculpture as an integral part of the style, with even larger portals and other figures on the facades of churches the location of the most important sculpture, until the late period, when large carved altarpieces and reredos, usually in painted and gilded wood, became an important focus in many churches. Gothic painting did not appear until around 1200 (this date has many qualifications), when it diverged from Romanesque style. A Gothic style in sculpture originates in France around 1144 and spread throughout Europe, becoming by the 13th century the international style, replacing Romanesque, though in sculpture and painting the transition was not as sharp as in architecture.

The majority of Romanesque cathedrals and large churches were replaced by Gothic buildings, at least in those places benefiting from the economic growth of the period—Romanesque architecture is now best seen in areas that were subsequently relatively depressed, like many southern regions of France and Italy, or northern Spain. The new architecture allowed for much larger windows, and stained glass of a quality never excelled is perhaps the type of art most associated in the popular mind with the Gothic, although churches with nearly all their original glass, like the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, are extremely rare anywhere, and unknown in Britain.

Most Gothic wall-paintings have also disappeared; these remained very common, though in parish churches often rather crudely executed. Secular buildings also often had wall-paintings, although royalty preferred the much more expensive tapestries, which were carried along as they travelled between their many palaces and castles, or taken with them on military campaigns—the finest collection of late-medieval textile art comes from the Swiss booty at the Battle of Nancy, when they defeated and killed Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and captured all his baggage train.[41]

As mentioned in the previous section, the Gothic period coincided with a greatly increased emphasis on the Virgin Mary, and it was in this period that the Virgin and Child became such a hallmark of Catholic art. Saints were also portrayed far more often, and many of the range of attributes developed to identify them visually for a still largely illiterate public first appeared.

During this period panel painting for altarpieces, often polyptyches and smaller works became newly important. Previously icons on panels had been much more common in Byzantine art than in the West, although many now lost panel paintings made in the West are documented from much earlier periods, and initially Western painters on panel were very largely under the sway of Byzantine models, especially in Italy, from where most early Western panel paintings come. The process of establishing a distinct Western style was begun by Cimabue and Duccio, and completed by Giotto, who is traditionally regarded as the starting point for the development of Renaissance painting. Most panel painting remained more conservative than miniature painting however, partly because it was seen by a wide public.

International Gothic describes courtly Gothic art from about 1360 to 1430, after which Gothic art begins to merge into the Renaissance art that had begun to form itself in Italy during the Trecento, with a return to classical principles of composition and realism, with the sculptor Nicola Pisano and the painter Giotto as especially formative figures. The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is one of the best known works of International Gothic. The transition to the Renaissance occurred at different times in different places - Early Netherlandish painting is poised between the two, as is the Italian painter Pisanello. Outside Italy Renaissance styles appeared in some works in courts and some wealthy cities while other works, and all work beyond these centres of innovation, continued late Gothic styles for a period of some decades. The Protestant Reformation often provided an end point for the Gothic tradition in areas that went Protestant, as it was associated with Catholicism.

The invention of a comprehensive mathematically based system of linear perspective is a defining achievement of the early-15th-century Italian Renaissance in Florence, but Gothic painting had already made great progress in the naturalistic depiction of distance and volume, though it did not usually regard them as essential features of a work if other aims conflicted with them, and late Gothic sculpture was increasingly naturalistic. In the mid-15th century Burgundian miniature (right) the artist seems keen to show his skill at representing buildings and blocks of stone obliquely, and managing scenes at different distances. But his general attempt to reduce the size of more distant elements is unsystematic. Sections of the composition are at a similar scale, with relative distance shown by overlapping, foreshortening, and further objects being higher than nearer ones, though the workmen at left do show finer adjustment of size. But this is abandoned on the right where the most important figure is much larger than the mason.

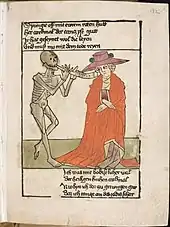

The end of the period includes new media such as prints; along with small panel paintings these were frequently used for the emotive andachtsbilder ("devotional images") influenced by new religious trends of the period. These were images of moments detached from the narrative of the Passion of Christ designed for meditation on his sufferings, or those of the Virgin: the Man of Sorrows, Pietà, Veil of Veronica or Arma Christi. The trauma of the Black Death in the mid-14th century was at least partly responsible for the popularity of themes such as the Dance of Death and Memento mori. In the cheap blockbooks with text (often in the vernacular) and images cut in a single woodcut, works such as that illustrated (left), the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying) and typological verse summaries of the bible like the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation) were the most popular.

Renaissance Humanism and the rise of a wealthy urban middle class, led by merchants, began to transform the old social context of art, with the revival of realistic portraiture and the appearance of printmaking and the self-portrait, together with the decline of forms like stained glass and the illuminated manuscript. Donor portraits, in the Early Medieval period largely the preserve of popes, kings and abbots, now showed businessmen and their families, and churches were becoming crowded with the tomb monuments of the well-off.

The book of hours, a type of manuscript normally owned by laymen, or even more often, laywomen, became the type of manuscript most often heavily illustrated from the 14th century onwards, and also by this period, the lead in producing miniatures had passed to lay artists, also very often women. In the most important centres of illumination, Paris and in the 15th century the cities of Flanders, there were large workshops, exporting to other parts of Europe. Other forms of art, such as small ivory reliefs, stained glass, tapestries and Nottingham alabasters (cheap carved panels for altarpieces) were produced in similar conditions, and artists and craftsmen in cities were usually covered by the guild system—the goldsmith's guild was typically among the richest in a city, and painters were members of a special Guild of St Luke in many places.

Secular works, often using subjects concerned with courtly love or knightly heroism, were produced as illuminated manuscripts, carved ivory mirror-cases, tapestries and elaborate gold table centrepieces like nefs. It begins to be possible to distinguish much greater numbers of individual artists, some of whom had international reputations. Art collectors begin to appear, of manuscripts among the great nobles, like John, Duke of Berry (1340–1416) and of prints and other works among those with moderate wealth. In the wealthier areas tiny cheap religious woodcuts brought art in an approximation of the latest style even into the homes of peasants by the late 15th century.

Virgin Mary

The oldest Byzantine icon of Mary, c. 600, encaustic, at Saint Catherine's Monastery retains much of Greek realist style.

The oldest Byzantine icon of Mary, c. 600, encaustic, at Saint Catherine's Monastery retains much of Greek realist style. Romanesque statue of the Virgin as Seat of Wisdom, 12th century

Romanesque statue of the Virgin as Seat of Wisdom, 12th century The "Ravensburger Schutzmantelmadonna", painted limewood of ca 1480, Virgin of Mercy type. Attributed to Michel Erhart.

The "Ravensburger Schutzmantelmadonna", painted limewood of ca 1480, Virgin of Mercy type. Attributed to Michel Erhart. "Hunt of the Unicorn Annunciation" (c. 1500) from a Netherlandish Book of Hours collected by John Pierpont Morgan. For the complicated iconography, see Hortus conclusus

"Hunt of the Unicorn Annunciation" (c. 1500) from a Netherlandish Book of Hours collected by John Pierpont Morgan. For the complicated iconography, see Hortus conclusus

Subsequent reputation

Medieval art had little sense of its own art history, and this disinterest was continued in later periods. The Renaissance generally dismissed it as a "barbarous" product of the "Dark Ages", and the term "Gothic" was invented as a deliberately pejorative one, first used by the painter Raphael in a letter of 1519 to characterise all that had come between the demise of Classical art and its supposed 'rebirth' in the Renaissance. The term was subsequently adopted and popularised in the mid 16th century by the Florentine artist and historian, Giorgio Vasari, who used it to denigrate northern European architecture generally. Illuminated manuscripts continued to be collected by antiquarians, or sit unregarded in monastic or royal libraries, but paintings were mostly of interest if they had historical associations with royalty or others. The long period of mistreatment of the Westminster Retable by Westminster Abbey is an example; until the 19th century it was only regarded as a useful piece of timber. But their large portrait of Richard II of England was well looked after, like another portrait of Richard, the Wilton Diptych (illustrated above). As in the Middle Ages themselves, other objects have often survived mainly because they were considered to be relics.

There was no equivalent for pictorial art of the "Gothic survival" found in architecture, once the style had finally died off in Germany, England and Scandinavia, and the Gothic Revival long focused on Gothic Architecture rather than art. The understanding of the succession of styles was still very weak, as suggested by the title of Thomas Rickman's pioneering book on English architecture: An Attempt to discriminate the Styles of English Architecture from the Conquest to the Reformation (1817). This began to change with a vengeance by the mid-19th century, as appreciation of medieval sculpture and its painting, known as Italian or Flemish "Primitives", became fashionable under the influence of writers including John Ruskin, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, and Pugin, as well as the romantic medievalism of literary works like Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1819) and Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831). Early collectors of the "Primitives", then still relatively cheap, included Prince Albert.

Among artists the German Nazarene movement from 1809 and English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood from 1848 both rejected the values of at least the later Renaissance, but in practice, and despite sometimes depicting medieval scenes, their work draws its influences mostly from the Early Renaissance rather than the Gothic or earlier periods - the early graphic work of John Millais being something of an exception.[43] William Morris, also a discriminating collector of medieval art, absorbed medieval style more thoroughly into his work, as did William Burges.

By the later 19th century many book-illustrators and producers of decorative art of various kinds had learned to use medieval styles successfully from the new museums like the Victoria & Albert Museum set up for this purpose. At the same time the new academic field of art history, dominated by Germany and France, concentrated heavily on medieval art and was soon very productive in cataloguing and dating the surviving works, and analysing the development of medieval styles and iconography; though the Late Antique and pre-Carolingian period remained a less explored "no-man's land" until the 20th century.[44]

Franz Theodor Kugler was the first to name and describe Carolingian art in 1837; like many art historians of the period he sought to find and promote the national spirit of his own nation in art history, a search begun by Johann Gottfried Herder in the 18th century. Kugler's pupil, the great Swiss art historian Jacob Burckhardt, though he could not be called a specialist in medieval art, was an important figure in developing the understanding of it. Medieval art was now heavily collected, both by museums and private collectors like George Salting, the Rothschild family and John Pierpont Morgan.

After the decline of the Gothic Revival, and the Celtic Revival use of Insular styles, the anti-realist and expressive elements of medieval art have still proved an inspiration for many modern artists.

German-speaking art historians continued to dominate medieval art history, despite figures like Émile Mâle (1862–1954) and Henri Focillon (1881–1943), until the Nazi period, when a large number of important figures emigrated, mostly to Britain or America, where the academic study of art history was still developing. These included the elderly Adolph Goldschmidt and younger figures including Nikolaus Pevsner, Ernst Kitzinger, Erwin Panofsky, Kurt Weitzmann, Richard Krautheimer and many others. Meyer Schapiro had immigrated as a child in 1907.

Jewish portrayals in medieval Christian art

The great majority of narrative religious medieval art depicted events from the Bible, where the majority of persons shown had been Jewish. But the extent to which this was emphasized in their depictions varied greatly. During the Middle Ages some Christian art was used as a way to express prejudices and commonly held negative views.

In Medieval Europe between the 5th and 15th century many Christians viewed Jews as enemies and outsiders due to a variety of factors.[45] They also tended to hate them for being both culturally and religiously different as well as because of religious teachings that held negative views of Jewish people such as portrayals of the Antichrist as Jewish.[46] The Jewish people's economic position as moneylenders, coupled with royal protections that were given to them, created a strained relationship between Jews and Christians. This strain manifested itself in several ways, one of which was through the creation of antisemitic and anti-Judaism art and propaganda that served the purpose of discrediting both Jews and their religious beliefs as well as spreading these beliefs even further into society. Late medieval images of Ecclesia and Synagoga represented the Christian doctrine of supersessionism, whereby the Christian New Covenant had replaced the Jewish Mosaic covenant[47] Sara Lipton has argued that some portrayals, such as depictions of Jewish blindness in the presence of Jesus, were meant to serve as a form of self-reflection rather than be explicitly anti-Semitic.[48]

In her 2013 book Saracens, Demons, and Jews, Debra Higgs Strickland argues that negative portrayals of Jews in medieval art can be divided into three categories: art that focused on physical descriptions, art that featured signs of damnation, and images that depicted Jews as monsters. Physical depictions of Jewish people in medieval Christian art were often men with pointed Jewish hats and long beards, which was done as a derogatory symbol and to separate Jews from Christians in a clear manner. This portrayal would grow more virulent over time, however Jewish women lacked similar distinctive physical descriptions in high medieval Christian art.[49] Art that depicted Jewish people in scenes that featured signs of damnation is believed to have stemmed from the Christian belief that Jews were responsible for the murder of Christ, which has led to some artistic representations featured Jews crucifying Christ.[50]

Jewish people were sometimes seen as outsiders in Christian dominated societies, which Strickland states developed into the belief that Jews were barbarians, which eventually expanded into the idea that Jewish people were monsters that rejected the "True Faith".[51] Some art from this time period combined these concepts and morphed the stereotypical Jewish beard and pointed hat imagery with that of monsters, creating art that made the Jew synonymous with a monster.[51]

The reasons for these negative depictions of Jews can be traced back to many sources, but mainly stem from the Jews being charged with deicide, their religious and cultural differences from their cultural neighbors, and how the antichrist was often depicted as Jewish in medieval writings and texts. The Jews were recently blamed for the death of Christ and were thus negatively depicted by the Christians in both art and scripture alike.[52]

Tensions between Jews and Christians were often high and this caused various stereotypes about Jews to form and become commonplace in their artistic depiction. Some of the attributes seen distinguishing Jews from their Christian counterparts in pieces of art are pointed hats, hooked and crooked noses, and long beards. By including these attributes in the portrayal of Jews in art, Christians succeeded in 'othering' Jews more than they already were and made them seem even more ostracized and segregated from the general population than they already were. Not only were these attributes added into depictions of Jewish People, they were generally portrayed as villainous and monstrous because of their supposed murder of Christ as well their rejection of Christ as the messiah.[52] This, coupled with the fact that they lived in largely insular groups separated them greatly from their Christian neighbors and caused a lasting rift between the groups that are reflected in the medieval art.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Heslop traces the beginning of the change to "around the twelfth century", quoted, 54; Zarnecki, 234

- ↑ Kitzinger (throughout), Hinks (especially Part 1) and Henderson (Chapters 1, 2 & 4) in particular are concerned with this perennial theme. Google books Archived 2022-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Fordham University Archived 2014-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Josiah Russell's figures - all estimates are of course very imprecise. See Consequences of the Black Death for more details.

- ↑ Li, H.; Ku, T. (2002). "Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Periods in Eastern China as Read from the Speleothem Records". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2002. Bibcode:2002AGUFMPP71C..09L.

- ↑ Dodwell (1982), pp. 22–23, and Chapter III

- ↑ The White Tower (Tower of London) was started in 1078, and some later royal apartments in the Tower of London survive, as do the hall and parts of Eltham Palace, the most significant medieval remains from an unfortified royal palace. Royal apartments survive in some castles.

- ↑ the small Carolingian(?) Equestrian Statue of an Emperor in the Carnavalet Museum in Paris, Hinks, 125-7; and the 12th(?)-century bronze of a man wrestling with a lion, variously considered English, German or Sicilian in origin, discussed by Henderson (1977), 135–139.

- ↑ Grocock, Chris has some calculations in Mayo of the Saxons and Anglican Jarrow, Evidence for a Monastic Economy Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, according to which sheep required only one third as much land per page as calves. 1,600 calves seems to be the standard estimate, see John, Eric (1996), Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England, Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 14, ISBN 0-7190-5053-7

- ↑ Campbell (1998), 29 – the following pages describe gold, pigments and other materials.

- ↑ Dates are discussed in Calkins (1979), xix-xx, Kitzinger (1955), 1, Beckwith (1964), 9.

- ↑ Henderson (1977), 8.

- ↑ Hinks, chapters 1 & 2, and Kitzinger, 1955, chapter 1.

- ↑ Kitzinger 1955, pp. 57–60.

- ↑ Atroshenko and Judith Collins cover the Eastern influences on Romanesque art in detail.

- ↑ Henderson 1977, ch. 2; Calkins 1979, chs 8 & 9; Wilson 1984, pp. 16–27 on early Anglo-Saxon art.

- ↑ Dodwell 1993, pp. 74(quote)–75, and see index.

- ↑ Hoffman, 324; Mack, Chapter 1, and passim throughout; The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711–1031), Metropolitan Museum of Art timeline Archived 2019-07-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved April 1, 2011

- ↑ Honour & Fleming 1982, pp. 256–262.

- ↑ Honour & Fleming 1982, p. 269.

- ↑ The Stones of Venice, chapter 1, paras 25 and 29 Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine; discussed pp. 49–56 here Archived 2022-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Beckwith 1964, pp. 206–209.

- ↑ Jones, Dalu & Michell, George, (eds); The Arts of Islam, Arts Council of Great Britain, 9, 1976, ISBN 0-7287-0081-6

- ↑ Caiger-Smith, chapters 6 & 7

- ↑ Hugh Thomas, An Unfinished History of the World, 224-226, 2nd edn. 1981, Pan Books, ISBN 0-330-26458-3; Braudel, Fernand, Civilization & Capitalism, 15-18th Centuries, Vol 1: The Structures of Everyday Life, William Collins & Sons, London 1981, p. 440: "If medieval Islam towered over the Old Continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific for centuries on end, it was because no state (Byzantium apart) could compete with its gold and silver money ..."; and Vol 3: The Perspective of the World, 1984, ISBN 0-00-216133-8, p. 106: "For them [the Italian maritime republics], success meant making contact with the rich regions of the Mediterranean - and obtaining gold currencies, the dinars of Egypt or Syria, ... In other words, Italy was still only a poor peripheral region ..." [period before the Crusades]. The Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD Archived 2019-02-16 at the Wayback Machine compiled by Angus Maddison show Iran and Iraq as having the world's highest per capita GDP in the year 1000

- ↑ Rather than along religious lines, the divide was between east and west, with the rich countries all lying east of the Nile: Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 382, table A.7. and Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 185, table 4.2 give 425 1990 International Dollars for Christian Western Europe, 430 for Islamic North Africa, 450 for Islamic Spain and 425 for Islamic Portugal, while only Islamic Egypt and the Christian Byzantine Empire had significantly higher GDP per capita than Western Europe (550 and 680–770 respectively) (Milanovic, Branko (2006): "An Estimate of Average Income and Inequality in Byzantium around Year 1000", Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 449–470 (468))

- ↑ The subject of Mack's book; the Introduction gives an overview

- ↑ Hoffman, Eva R. (2007): Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century, pp.324f., in: Hoffman, Eva R. (ed.): Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-5

- ↑ Mack, 4

- ↑ Hinks 1974, Parts II & III; Kitzinger 1955, ch. 2; Calkins 1979, chs 11 & 12.

- ↑ Kitzinger 1955, pp. 75–77.

- ↑ Dodwell, 56 & Beckwith, 39-43.

- ↑ A complicated subject, covered in Dodwell (1993), 175, 223, 258 among many other passages.

- ↑ Beckwith 1964, pp. 145–149.

- ↑ Henderson 1977, pp. 190(quote)–195.

- ↑ Dodwell (1993), 167-169

- ↑ Honour & Fleming 1982, pp. 277 & 284–288. Beckwith 1964, p. 149, says the bronze column at Hildesheim of c. 1020 "cannot be said to be Romanesque ... It stands apart as a curious Ottonian pastiche of a Roman monument ... never to be repeated"

- ↑ Harpham, Geoffrey Galt (2006-01-01), Bernard's letter, Davies Group Publishers, ISBN 978-1-888570-85-4, retrieved 2011-06-11

- ↑ Dodwell (1993), 212–214. The MS is the Dijon Moralia in Job of Gregory the Great.

- ↑ Honour & Fleming 1982, p. 271.

- ↑ Karkov, Catherine E. (2016), "Hardham Wall Paintings", in Paul E. Szarmach; M. Teresa Tavormina; Joel T. Rosenthal (eds.), Medieval England: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, p. 337, ISBN 978-1-138-06208-5

- ↑ The Historical Museum of Bern has many of the best pieces, and these and others were shown in an exhibition on Philip in Bern, Bruges and Vienna in 2008-9.

- ↑ Plummer 1964, plates 1–2.

- ↑ In works like this Archived 2019-07-31 at the Wayback Machine, stylistically very different from the finished painting.

- ↑ Kitzinger 1955, pp. 1(quote)–2.

- ↑ Holcomb, Barbara Drake; Holcomb, Melanie (June 2008). "Jews and the Arts in Medieval Europe". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- ↑ Mittman, Asa Simon; Dendle, Peter J. (2013). The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 383. ISBN 9781472418012.

- ↑ Rose, Christine, "The Jewish Mother-in-law; Synagoga and the Man of Law's Tale", pp. 8-11, in Delany, Sheila (ed), Chaucer and the Jews : Sources, Contexts, Meanings, 2002, Routledge, google books Archived 2022-11-23 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 0-415-93882-1, ISBN 978-0-415-93882-2

- ↑ Lipton, Sara (2014-11-04). Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography. Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 9780805079104.

- ↑ Lipton, Sara (2008). "Where Are the Gothic Jewish Women? On the Non-Iconography of the Jewess in the Cantigas de Santa Maria". Jewish History. 22 (1/2): 139–177. doi:10.1007/s10835-007-9056-1. JSTOR 40345545. S2CID 159967778.

- ↑ Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003). Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0691057192.

- 1 2 Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003). Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton University Press. pp. 241–247. ISBN 0691057192.

- 1 2 Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003), Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

References

- Atroshenko, V. I.; Collins, Judith (1985), The Origins of the Romanesque, London: Lund Humphries, ISBN 0-85331-487-X

- Alexander, Jonathan (1992), Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-05689-3

- Backhouse, Janet; Turner, D. H.; Webster, Leslie, eds. (1984), The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art, 966–1066, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0-7141-0532-5

- Caiger-Smith, Alan, Lustre Pottery: Technique, Tradition and Innovation in Islam and the Western World (Faber and Faber, 1985) ISBN 0-571-13507-2

- Beckwith, John (1964), Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-20019-X

- Calkins, Robert G. (1983), Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press

- Calkins, Robert G. (1979), Monuments of Medieval Art, New York: Dutton, ISBN 0-525-47561-3

- Campbell, Lorne (1998), The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings, National Gallery Catalogues (new series), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 1-85709-171-X

- Cormack, Robin (1985), Writing in Gold, Byzantine Society and its Icons, London: George Philip, ISBN 0-540-01085-5

- Cormack, Robin (1997), Painting the Soul; Icons, Death Masks and Shrouds, London: Reaktion Books

- Dodwell, C. R. (1982), Anglo-Saxon Art, A New Perspective, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-0926-X (US edn. Cornell, 1985)

- Dodwell, C. R. (1993), The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Henderson, George (1977) [1972], Early Medieval Art (rev. ed.), Harmondsworth: Penguin

- Heslop, T. A. (Sandy), in Dormer, Peter (ed.), "How strange the change from major to minor; hierarchies and medieval art", in The Culture of Craft, 1997, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0719046181, 9780719046186, google books

- Hinks, Roger (1974) [1935], Carolingian Art, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-06071-6

- Hoffman, Eva R. (2007): Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century, in: Hoffman, Eva R. (ed.): Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-5

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (1982), "Honour", A World History of Art, London: Macmillan

- Kitzinger, Ernst (1955) [1940], Early Medieval Art at the British Museum (2nd ed.), British Museum

- Lasko, Peter (1972), Ars Sacra, 800–1200 (nb, 1st ed.), Penguin History of Art (now Yale), ISBN 978-0-300-05367-8.

- Mack, Rosamond, Bazaar to piazza: Islamic trade and italian art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-520-22131-4, google books

- Mâle, Emile (1913), The Gothic Image, Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century (English trans. of 3rd ed.), London: Collins

- Pächt, Otto (1986), Book Illumination in the Middle Ages, London: Harvey Miller, ISBN 0-19-921060-8

- Plummer, John (1964), The Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves, New York: Pierpont Morgan Library

- Rice, David Talbot (1968), Byzantine Art (3rd ed.), Penguin Books

- Ross, Leslie (1996), Medieval Art, a topical dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-29329-5

- Runciman, Steven (1975), Byzantine Style and Civilization, Baltimore: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-021827-0

- Schapiro, Meyer (1977), Selected Papers, volume 2, Romanesque Art, London: Chatto & Windus, ISBN 0-7011-2239-0

- Schapiro, Meyer (1980), Selected Papers, volume 3, Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art, London: Chatto & Windus, ISBN 0-7011-2514-4

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003), Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Syndicus, Eduard (1962), Early Christian Art, London: Burns & Oates

- Weitzmann, Kurt; Chatzidakis, Manolis (1982), The Icon, London: Evans Brothers, ISBN 0-237-45645-1 (trans of Le Icone, Montadori 1981)

- Wilson, David M. (1984), Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press, ISBN 0-87951-976-2

- Zarnecki, George and others; English Romanesque Art, 1066–1200, 1984, Arts Council of Great Britain, ISBN 0728703866

Further reading

- Kessler, Herbert L., "On the State of Medieval Art History", The Art Bulletin, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 166–187, JSTOR

- Husband, Timothy (1986). The wild man: medieval myth and symbolism. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-254-4.

- The Art of medieval Spain, A.D. 500-1200. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1993. ISBN 0-87099-685-1.

External links

- Stones, Allison, Glossary of Medieval Art and Architecture, University of Pittsburgh

- Weitzmann, Kurt, Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.

- Medieval art collection at the Cleveland Museum of Art

- Medieval Art and the Cloisters at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Collections at the Musée de Cluny

- Database of medieval painted manuscripts, at the British Library site

- Illuminated manuscript project at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) site