Mehmed Râshid Pasha | |

|---|---|

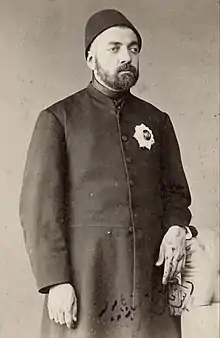

Rashid Pasha c. 1870s | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office November 1875 – 15 June 1876 | |

| Monarch | Abdulaziz (1861–1876) |

| Preceded by | Saffet Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Saffet Pasha |

| In office 15 May 1873 – May 1874 | |

| Preceded by | Saffet Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Arifi Pasha |

| Vali of Syria | |

| In office August 1866 – September 1871 | |

| Preceded by | As'ad Mukhlis Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Abdullatif Subhi Pasha |

| Vali of Smyrna | |

| In office c. 1862 – Summer 1866 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1824 Egypt, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 15 June 1876 Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

Mehmed Rashid Pasha (Turkish: Mehmed Râşid Paşa, Arabic: محمد راشد باشا, romanized: Muḥammad Rāshid Basha; 1824–15 June 1876) was an Ottoman statesman who served as the vali (governor) of Syria Vilayet in 1866–1871 and as minister of foreign affairs of the Ottoman government in 1873–1874 and 1875 until his death. Rashid Pasha was raised in Egypt where his father was an aide of the governor Muhammad Ali and was educated in Paris before joining government service in Istanbul in 1851. There he became a protege of the grand vizier Ali Pasha, a key figure in the empire-wide Tanzimat reforms. After the latter was reappointed grand vizier in 1866, Rashid Pasha was appointed governor of the Damascus-centered Syria Vilayet which extended from Tripoli and Hama in the north to Palestine and Transjordan in the south.

As governor, Rashid Pasha enacted numerous administrative reforms, including the creation of the Damascus and Beirut municipal councils, the Syrian provincial council and the Syrian parliament, while ensuring that the office of amir al-hajj (commander of the annual Hajj caravan) was only filled by a local. He launched numerous public works projects, significantly expanding Syria's road and telegraph networks. He also sought to bring order to Syria's chaotic land ownership laws and encouraged private purchases of state-owned land, which ultimately benefited the urban elite to the detriment of the peasantry. His main goal was to integrate Syria and its hinterland firmly into the Ottoman state after a long period of virtual autonomy and imperial neglect. To that end, he launched military campaigns in the Alawite-dominated coastal range, the central Syrian steppe and the southern Hauran and Balqa plains, all rural regions that long resisted Ottoman taxation and conscription. Unlike his predecessors, however, Rashid Pasha ultimately achieved the cooperation of the mutually hostile Muslim plainsmen, Druze mountaineers and Bedouin tribesmen by equitably distributing resources and duties among them while maintaining a strong military presence. He viewed his strategy as necessary for the prosperity of the region and joint resistance against increasing European commercial encroachments in the lucrative Syrian grain trade.

Concurrent with Ali Pasha's dismissal as grand vizier in 1871, Rashid Pasha was dismissed from the governorship of Syria. Two years later he was appointed minister of planning before a cabinet reshuffle that same year made him minister of foreign affairs. He was replaced in May 1874 and sent to Vienna as the Ottoman ambassador to Austria-Hungary. However, he was reappointed minister of foreign affairs in November 1875. Rashid Pasha continued in this office until he was gunned down by Hassan Bey, a disgruntled officer, during a cabinet meeting in the home of Midhat Pasha. Hassan's target was the minister of war, Huseyin Avni Pasha, who was also killed.

Early life and career

Rashid Pasha was born and raised in Egypt in 1824.[1][2][3] His father, Hasan Haydar Pasha,[4] was an ethnic Turk from Drama in Macedonia,[1] who served in the court of the powerful vali (governor), Muhammad Ali.[1][2] In 1844, Rashid was sent to study in Paris as part of an annual education mission from Egypt to France. In 1849 Rashid returned to Egypt after completing his education and then two years later followed his father and other Turkish Egyptian officials to the Ottoman capital in Istanbul.[1]

In Istanbul, Rashid became a protege of Grand Vizier Mehmed Ali Pasha, a reformist Ottoman statesman involved with the establishment of the empire-wide Tanzimat reforms.[5] The command of Arabic and French he developed during his youth in Egypt and France had been "key to his advancement" according to the historian Leila Hudson.[2] Rashid entered the imperial service and over the years served various provincial posts.[1] Like Mehmed Ali Pasha, Rashid had spent part of his career in the Translation Bureau of the Foreign Ministry.[6]

According to the historian Butrus Abu-Manneh, Rashid Pasha was appointed the governor of the Izmir-centered Smyrna Vilayet at the relatively young age of 40.[1] However, he is mentioned as governor of Smyrna as early as 1862. During that year he inaugurated a train station in the town of Aysalok along the railway opened between Aidin and Izmir. The station paved the way for Aysalok's transformation into a resort town.[7]

Governor of Syria

.jpg.webp)

In the early summer of 1866,[1] a power shuffle in the Sublime Porte (Ottoman central government), resulted in the reappointment of Rashid Pasha's mentor Mehmed Ali Pasha as grand vizier;[2] Mehmed Ali Pasha had been appointed and dismissed from the grand vizierate in 1852, 1855–1856, 1858–1859 and 1861.[8] Meanwhile, in Syria Vilayet, a province centered in Damascus, Governor As'ad Mukhlis Pasha canceled the province's grain supply contracts with European merchants and their associated local contractors and ordered the grain harvests to be redirected to state warehouses; grain was the major cash crop of Syria. Incensed, the European consuls demanded that As'ad Mukhklis Pasha be dismissed.[9] In August 1866,[10] Mehmed Ali Pasha affirmed and appointed Rashid Pasha valī of Syria.[2][9]

Reorganization and reforms

The Syria Vilayet was formed in 1865, combining the eyalets of Damascus and Sidon.[6][11] The province extended from Tripoli and Hama in the north to Palestine and Transjordan in the south,[5] but excluded the autonomous Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate.[12] According to the historian John Spagnolo, Rashid Pasha was "intent on reinvigorating the Ottoman Empire" and was "as efficient and imaginative in the exercise of his functions as the prevailing state of the Empire permitted",[6] while Abu-Manneh noted that he "worked indefatigably for the integration of the provinces".[5] By 1868, Syria was administratively divided into the eight sanjaks (first-level districts) of Damascus, Beirut, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Acre, Hama, Hauran and Nablus.[13]

Rashid Pasha established a new municipal council in Damascus and a new administrative council for the province. To elicit local support for the reorganized administration, several Damascene notables were given posts in the councils or other provincial posts. He reformed the office of amir al-hajj (commander of the annual Hajj caravan to Mecca), increasing the post's salary and ensuring that only locals were appointed to the office.[14] Notables from Beirut (former capital of Sidon Eyalet), the city of Sidon and the subdistricts of Rashaya, Hasbaya and the eastern Beqaa Valley lodged complaints to the Sublime Porte in October 1867 alleging that their interests were being neglected by the administration in Damascus. The petitions were penned by former employees of Daud Pasha, the governor of Mount Lebanon, who strove to annex the areas to his governorship and may have played a role in the petitions.[15] Rashid Pasha subsequently visited Sidon to hear local grievances and replace the city's qaimmaqam (governor of a qadaa or 'second-level district').[16] Rashid Pasha oversaw the first Syrian parliament (Majlis Suriye) in Beirut in December 1867 or January 1868, during which four representatives (two Muslims and two non-Muslims) from each sanjak convened to discuss new commercial and infrastructural projects and administrative reforms.[16][17] In 1868 he authorized the establishment of the Beirut Municipal Council.[18]

In line with the 1858 Land Code, large state-owned tracts in the Hauran plain and the Beqaa Valley were put up for auction. Rashid Pasha encouraged private investment in land and sought to speedily register deeds to bring order to the chaotic state of land ownership in Syria. In his pursuit of these goals, he often supported the interests of wealthy businessmen from the major cities against the interests of the peasantry. In general, many of the urban businessmen Rashid Pasha courted lacked adequate capital for mass land acquisition during his term, and investments in land did not accelerate until the trade depression and rural hardships of the 1870s, after he left office.[14]

Public works

Rashid Pasha launched a campaign to upgrade Syria's infrastructure.[17] Through the Damascus Administrative Council, these projects were commenced to facilitate access to the city's rural hinterland and encourage the expansion of agriculture.[14] In 1868, a resolution was passed by the parliament approving the construction of a carriage road from the northern town of Ma'arra, southward through Hama, Homs, Baalbek and Anjar to connect with the Beirut–Damascus highway.[19] Inland-to-coastal roads that connected Homs and Tripoli, Nablus and Sidon, Tibnin and Tyre, and Suq al-Khan and Acre were built as well. A carriage road between Damascus and Palestine was also opened to ease overland trade with Egypt. Furthermore, the existing Jerusalem–Nablus route and the coastal routes that connected Gaza to Jaffa and Beirut with Sidon were repaired. Rashid Pasha attempted to build a road through the Syrian Desert connecting Damascus with Baghdad, but the project fell through.[17]

A major expansion of the telegraph network in Syria was initiated by Rashid Pasha and telegraph offices were set up in all of the province's major towns. He also directed that European languages were able to be transmitted through the network in addition to Turkish. The 19th-century Syrian historian Muhammad Husni asserts that Rashid Pasha was infatuated with the telegraph, spending hours in the telegraph office sending and receiving messages.[17] During Rashid Pasha's rule, Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri and other prominent Damascenes lobbied the British consul of Damascus, Richard Burton, to gain British financial backing for a large railroad network in Syria.[14]

Promotion of education and literature

The Nahda (Arabic literary renaissance) in Syria dates to Rashid Pasha's governorship. According to Hudson, Rashid Pasha, as a modernist, took a "personal interest in spreading literacy and in building an educational infrastructure."[2] Primary schools were founded in Damascus, Beirut and Jerusalem with his support. Under his governorship, a provincial newspaper, Suriyya, and provincial salnamas (yearbooks) were first published, while private literary journals also began to circulate.[2] In 1868 he authorized the reestablishment of the Syrian Scientific Society, a group composed of Syrian entrepreneurs and patrons of literature and the arts.[20]

Centralizing the hinterlands

Rashid Pasha viewed a prominent military presence as key to the success of his infrastructural, administrative and educational initiatives.[17] One of his key policies was extending actual administrative rule and law enforcement to Syria's hinterlands.[21] To that end, he launched campaigns to suppress the Bedouin tribes of the desert fringes.[17][21] Bedouin mobility and depredations against agricultural settlements were the main cause of instability in the Syrian countryside and fostered brigandage. Concerted efforts against the Bedouin began in 1863 under Governor Fuad Pasha, entailing a military campaign by a newly conscripted army of urban Syrians equipped with modern rifles from the Crimean War and new fortifications between the settled countryside and the Syrian Desert.[22]

Northern and central Syria

Two months into his term, Rashid Pasha made campaign preparations against the Alawite clans in the coastal mountains east of Latakia and Tripoli, mainly for evading conscription. Operations occurred over months until government authority and conscription orders were enforced across the mountain range. In 1867, the Alawite mountaineers used the diversion of imperial troops from Syria to Crete, where a rebellion was raised against the Ottomans, as an opportunity to raid neighboring villages. Rashid Pasha consequently renewed the campaign and reimposed control over the mountains. Conscription orders were carried out successfully during that year and in August 1868. The Alawite sheikhs (chieftains) informed Rashid Pasha that the success was partly due to the releases issued by his deputy governor of Tripoli, Khurshid Pasha, for numerous conscripts who had been "unjustly recruited" in 1866.[10] The success was also attributed to the participation of local Alawite leaders in the supervision of conscription. In May 1870, the Alawite clans refused to provide army recruits and resumed raids against nearby villages, prompting a full-scale campaign by Rashid Pasha, which resulted in the plunder and burning of several villages, the arrest and life imprisonment of thirteen Alawite sheikhs, the confiscation of 8,000 weapons and the conscription of 250 Alawite men.[23]

Also in 1866–1867, Rashid Pasha subdued the Bedouin tribes in the eastern countryside of Homs and Hama.[21] He commanded those military expeditions,[14] and was assisted by the governor of Aleppo Vilayet through the use of telegraph communication and surveillance. In 1868, he established army garrisons in Palmyra and other rural towns to deter Bedouin raiders, and compelled the tribes of northern Syria to fight alongside his forces in his campaigns against the southern tribes that year.[24]

Hauran

In the Hauran, Rashid Pasha's modernization and centralization efforts partly consisted of winning the support of rural factions. The competing and often warring groups consisted of the Bedouin tribes, the Druze mountaineer sheikhs and the mostly Muslim peasant sheikhs of the plains, all of whom generally viewed the Ottoman government as an alien authority whose sole purpose was to tax and conscript their men. Rashid Pasha attempted to persuade the rural factions that the lands in which they lived possessed sufficient resources to share, and that it was mutually beneficial for the factions and the government to jointly exploit the land. He argued that a united front of the inhabitants and the state could effectively counter the increasing European interference in the region's affairs. The British consul in Damascus, Richard Wood, wrote that Rashid Pasha's efforts sought to instill in the province's inhabitants "a sense of community of material, social, and political interests—a national spirit, in fact, of which the government will be regarded as the highest expression".[25]

Rashid Pasha extended direct rule to the plain of Hauran, which was Syria Vilayet's principal grain-producing region, designating it a sanjak under Kamil Pasha, a Turkish mutassarif (governor of a sanjak). He ended the peasants' withholding of grain supplies in protest at the government monopoly set up by As'ad Mukhlis Pasha and the presence of imperial troops in the Hauran by offering the peasants tax concessions; he refused to withdraw government troops, however.[25] In December 1866, Rashid Pasha met the powerful Druze sheikh Ismail al-Atrash in Damascus and appointed him mudir (subdistrict governor) of Jabal al-Druze, the mountainous area of the eastern Hauran.[26] He also allocated adequate grazing lands for the flocks of the Bedouin Ruwallah and Wuld Ali tribes, both major rivals of the Druze clans and the Hauran peasantry.[25] Al-Atrash's appointment upset his Druze rivals from the Bani Amer and Al Hamdan clans.[26] In June 1868, the latter two allied with the Bedouin Sulut tribe of the Lajat, a barren and lawless region north of Jabal al-Druze, against the Bani al-Atrash. To avert conflict, Rashid Pasha held a summit of the Druze sheikhs in which Ismail was dismissed in favor of his son Ibrahim. Soon after, Rashid Pasha reorganized Jabal al-Druze into a qadaa of Hauran administered by a council headed by a qaimmaqam. The new qadaa was divided into four nahiyas (subdistricts) based on the boundaries of the existing Druze mashaykha (sheikhdoms).[27]

Balqa

In 1867, Rashid Pasha oversaw plans to assert state control over the Balqa,[14] a region of Transjordan extending between Wadi Mujib in the south to the Zarqa River in the north.[21] Before Rashid Pasha's governorship, the Ottomans had not been able to tax the Balqa.[14] Despite the region's abundant fertile plains, it lacked permanent settlements, besides the fortress town of al-Salt, due to incessant Bedouin raids. The peasantry cultivated the Balqa's plains through extortionate protection agreements, known as khuwwa, with the Bedouin tribes in which the latter would receive a share of the harvest in return for not disturbing the peasants.[28] Rashid Pasha sought to end this traditional arrangement and obtain tax arrears, set up an administrative body over the region and force the Bedouin tribes (the Adwan, Sardiyah, Bani Sakhr and Sirhan) to submit to state authority.[29]

Rashid Pasha had already secured the state's authority in the Hauran and enlisted support for the planned Balqa expedition from the Hauran plainsmen, Druze sheikhs and Bedouin tribes, namely the Ruwallah, Wuld Ali and Bani Hasan.[29] Rashid Pasha personally led government expeditions in the Balqa.[14] He set off to subdue the region at the head of three infantry battalions, nine regular and irregular cavalry squadrons and light artillery. The size of this force compelled the Muslims and Christians of al-Salt to abandon their alliance with the Adwan leader, Dhiyab al-Humud, and submit to Rashid Pasha; he peacefully entered the city on 17 August and forced the Bedouin to withdraw southward to Hisban. In al-Salt, Rashid Pasha established the qadaa of Balqa with an elected council of local notables headed by an appointed Kurdish qaimmaqam from Damascus, Faris Agha Kudru. He repaired the city's fortress, which had been heavily damaged during the 1834 peasants' revolt, and turned it into an army barracks. He seized massive quantities of grain and livestock from al-Salt and its vicinity in lieu of tax arrears; the value of this confiscation amounted to three million piasters.[30]

On 30 August, he pursued the Adwan tribesmen, and in the ensuing four-hour battle the Adwan lost fifty men and retreated south toward al-Karak. Dhiyab surrendered to Rashid Pasha in Nablus in October 1867. According to the historian Eugene Rogan, Rashid Pasha's "campaign represented an unprecedented Ottoman intrusion into Jordan".[31] By 1868, the Irbid-based qadaa of Ajlun, part of Hauran Sanjak, and the as-Salt-based qadaa of Balqa, part of Nablus Sanjak, were formally recorded as administrative units.[31] Later in 1868, Rashid Pasha began efforts to establish a qadaa centered in Ma'an, a fortified oasis town south of the Balqa. He petitioned the Sublime Porte to approve the measure, which they did, but it was not implemented until 1872 during the rule of his successor, Abdülletif Subhi Pasha.[32]

In the summer of 1869, the Adwan and Bani Sakhr, traditional rivals, joined forces to challenge Rashid Pasha's assertion of state rule. They raided the village of al-Ramtha in Hauran, prompting Rashid Pasha to launch a large-scale campaign against them out of concern that a lesser response to the Bedouin affront to state authority would threaten his administrative reforms in the Syrian hinterlands.[33] Rashid Pasha brought along the British and French consuls to witness his two-column expedition, which manifested as several pincer assaults on the tribes. Among the latter, the Bani Sakhr and Bani Hamida were pinned down in the deep gorge of Wadi Wala, surrendered, and were fined 225,000 piasters in compensation for the expedition's expenses. Rogan has stated that "if the first Balqa expedition introduced direct Ottoman rule, the second campaign confirmed that the Ottomans were in Jordan to stay".[32]

Southern Palestine

Rashid Pasha attempted to force the nomadic Bedouin of southern Palestine to sedentarize. To that end, he issued orders to the Bedouin in the desert around Gaza to replace their tents with huts, which the Bedouin considered an existential threat to their way of life. The fifteen soldiers sent to enforce the order were killed by Tiyaha tribesmen upon arrival, prompting Rashid Pasha to send a punitive expedition against the tribe, which seized its entire sheep flocks and camel herds and sold them to the peasantry in Jerusalem. Afterward, the Bedouin gained the protection of Isma'il Pasha, Egypt's autonomous khedive (viceroy), who prevented further attempts by Rashid Pasha to settle the tribes.[34]

Cooptation of the aghawat

One of Rashid Pasha's first acts as governor was the arrest of Muhammad Sa'id Agha (son of Shamdin Agha), a powerful Kurdish Damascene agha (commander of irregulars; pl. aghawat).[25] The aghawat wielded significant influence in Damascus and dominated relations between the city and its hinterland.[35] Rashid Pasha's imprisonment of Muhammad Sa'id was a manifestation of his centralization efforts.[25] However, he ultimately decided to co-opt the aghawat by employing them to assist in the centralization of the province's hinterlands. Accordingly, in 1867, he released Muhammad Sa'id and assigned him to help direct the expedition in the Balqa. In addition to Muhammad Sa'id, other Kurdish aghawat, namely Mahmud Agha Ajilyaqin and Ahmad Agha Buzu, were also appointed roles in the Balqa expedition and were each appointed to the office of amir al-hajj at some point during Rashid Pasha's governorship. Another agha of Damascus, Haulu Agha al-Abid was appointed the qaimmaqam of Hauran in the latter half of Rashid Pasha's term.[14]

Dismissal

Rashid Pasha was recalled from Damascus immediately after the death of his mentor Grand Vizier Ali Pasha in September 1871.[36] The new grand vizier, Mahmud Nedim Pasha,[36] appointed the more conservative Abdullatif Subhi Pasha in Rashid's place.[37] According to Spagnolo, Rashid Pasha's "administration and integrity made him to be remembered as one of the best Ottoman governors of Syria".[6]

Minister of Foreign Affairs

On 11 March 1873, Rashid Pasha was appointed the minister of public works in the government of Grand Vizier Ahmed Esad Pasha.[38] Government changes during this period were characteristically frequent and on 15 May the cabinet, by then led by Grand Vizier Mehmed Rushdi Pasha, was reshuffled and Rashid Pasha replaced Saffet Pasha as minister of foreign affairs.[38] In May 1874 Ahmed Arifi Pasha was appointed foreign minister,[39] and Rashid Pasha was sent to Vienna to serve as the ambassador to Austria-Hungary.[40][41] He was reappointed foreign minister in the government of Grand Vizier Mahmud Nedim Pasha in November 1875, replacing Saffet Pasha, who had been appointed in January of that year.[42]

Aceh War

During the Aceh War between the Aceh Sultanate and the Dutch East Indies, Rashid Pasha's predecessor assured the French, British, Russian, German and Austrian ambassadors that the Ottomans would not intervene in the conflict amid efforts by Acehenese politicians in Istanbul to obtain Ottoman backing.[43] At the beginning of June 1873 Rashid Pasha informed a major advocate of Aceh, Abdurrahman az-Zahir, that Aceh was too distant from the Empire to elicit intervention.[44] After public pressure to aid the Acehenese was roused by the publication of two firmans from 1567 and 1852 acknowledging Aceh as Ottoman sovereign territory, the cabinet convened on 13 June. Most of the ministers dismissed the firmans as confirmations of a religious rather than political relation or called for a statement expressing concerns about a war in Aceh. Rashid Pasha advocated an official protest against the Dutch government and imperial honor for the Sultan of Aceh Alauddin Mahmud Syah II.[45] In July Rashid Pasha obtained documents signed by the Sultan of Aceh and his deputies submitting the country to Ottoman sovereignty and calling for a governor to be appointed by the Sublime Porte. Although the letter prompted a response by Sultan Abdulaziz (r. 1861–1876), pressure from European governments limited it to a letter to the Dutch proposing to mediate the conflict and, later, an official warning against Dutch actions in Aceh, as well as an imperial honor for Abdurrahman az-Zahir in December.[46]

Yemen

In 1873 Ottoman troops from Yemen Vilayet had been deployed to the south Arabian sultanates of Lahj and Hawshabi, both part of the British protectorate of Aden but claimed as sovereign territory of the Ottoman sultan. The Sultan of Lahj asserted the Ottoman presence was unwelcome, but his brother had called on the Ottomans to intercede on his behalf over a dispute with a resident of the sultanate. The British ambassador to Istanbul petitioned the Sublime Porte to force the Yemen governor's troops to withdraw and informed Rashid Pasha that Britain maintained a treaty with the south Arabian sultanates and objected to Ottoman interference. Although Rashid Pasha instructed the governor of Jerusalem, Kamil Pasha, to investigate the situation in Yemen and prevent its governor from actions against tribes which claimed British protection, the ambassador claimed such promises were meaningless and that Rashid Pasha had given him "the run around".[47] In a compromise proposal, on 26 January 1874, Rashid Pasha communicated to the British that the Sublime Porte would "not compromise [its] sovereignty over Lahj but would not interfere with treaty obligations between the shaykhs and others" and that the presence of imperial Ottoman troops in Yemen was "by right" as "Arabia is the cradle of Islam; the Sultan is the Prophet's khalifah; he has rights and obligations vis-a-vis the Holy Cities [Mecca and Medina]".[48]

Capitulations in Syria and Palestine

On 12 May 1874 Rashid Pasha made a formal request to the British to terminate protection of an undefined number of Ashkenazi Jews in Syria and Palestine.[49] In the 1850s, about 1,000 Jews had been given British protection, a number which continued to grow in the following decades.[50] Although generally recognizing the Ottoman imperial government to be among the most religiously tolerant in the world, Ashkenazi Jews who had settled in Ottoman territory lacked trust in local officials, who had been known to be corrupt or incompetent, and preferred European protection. Per capitulations treaties with the Sublime Porte, European governments could use force if their citizens or protégés were harmed, though in practice, consular warnings to local officials proved sufficient.[51] The Ottoman government initially favored the protection system as it increased foreigners' security and promoted trade while saving the Ottomans from security responsibilities for foreign citizens. Beginning in the 1850s, the Ottoman government began to consider the capitulations as a humiliating interference in its sovereign affairs.[52] In conveying the Sublime Porte's objectives of persuading foreign Jews to acquire Ottoman citizenship and refusing the European powers' rights of protection, Rashid Pasha informed the British that "Times have changed ... protection has become an obsolescent institution ... a fruitful source of trouble and dispute".[49]

Death

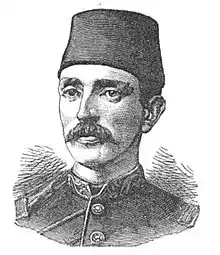

During a meeting of top cabinet officials in the Istanbul home of Midhat Pasha on 15 June 1876, Rashid Pasha was gunned down with a revolver by Cerkes Hassan Bey, the Circassian brother-in-law of Sultan Abdulaziz.[53][54] Hassan Bey's target was War Minister Huseyin Avni Pasha, who was killed immediately.[lower-alpha 1][53][54] Rashid Pasha died in the ensuing scuffle, along with Midhat's servant Ahmad Agha.[53][54] As Hassan Bey fled the scene, police gendarmes and regular troops engaged him in a running battle in which two soldiers were killed before Hassan Bey was apprehended.[54] After a brief trial, he was hanged on 17 June or 18 June.[53][54] Rashid Pasha is buried in the cemetery of the Fatih Mosque in Istanbul.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Hassan Bey had been angry and aggrieved at the dismissal and subsequent suicide of Sultan Abdulaziz in May 1876 and the death of his sister Nesrin Kadın during an abortion at the same time. In the aftermath of these events, Hassan felt he was consequently mistreated by Huseyin Avni Pasha who, believing Hassan was dangerous, assigned him to a faraway army post in Baghdad.[54]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Abu-Manneh 1992, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hudson 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Kosev 1982, p. 127, note 63.

- 1 2 Günüç 2007, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 Abu-Manneh 1999, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 Spagnolo 1971, p. 160.

- ↑ Clarke 1863, p. 45.

- ↑ Dânişmend 1971, pp. 78, 81–83.

- 1 2 Schilcher 1981, p. 172.

- 1 2 Talhami 2011, p. 37.

- ↑ Abu-Manneh 1992, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Sluglett 2010, p. 534, note 8.

- ↑ Burton 1876, pp. 99–100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Schilcher 1981, p. 174.

- ↑ Spagnolo 1971, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 Spagnolo 1971, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hudson 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Hill 2020, p. 43.

- ↑ Issawi 1988, p. 12.

- ↑ Hill 2020, pp. 42–44.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogan 1994, p. 38.

- ↑ Hudson 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Talhami 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Hudson 2008, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schilcher 1981, p. 173.

- 1 2 Firro 1992, p. 191.

- ↑ Firro 1992, p. 192.

- ↑ Rogan 1994, pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 Rogan 1994, p. 39.

- ↑ Rogan 1994, pp. 39–40.

- 1 2 Rogan 1994, p. 40.

- 1 2 Rogan 1994, p. 41.

- ↑ Rogan 1994, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Palmer 1871, p. 298.

- ↑ Schilcher 1981, pp. 160, 162–163.

- 1 2 Abu-Manneh 1992, p. 20.

- ↑ Abu-Manneh 1992, p. 22.

- 1 2 The American Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1873, Volume 13. New York: D. Appleton. 1874. p. 744.

- ↑ Maynard 1877, p. 601.

- ↑ Manna 2000, p. 284.

- ↑ Schölch 1993, p. 244.

- ↑ Harris 1969, p. 156.

- ↑ Göksoy 2011, p. 87.

- ↑ Göksoy 2011, p. 88.

- ↑ Göksoy 2011, p. 89.

- ↑ Göksoy 2011, p. 90.

- ↑ Farah 1998, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Farah 1998, p. 49.

- 1 2 Friedman 1998, p. 36.

- ↑ Friedman 1998, p. 32.

- ↑ Friedman 1998, p. 30.

- ↑ Friedman 1998, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1876, Volume 16. New York: D. Appleton and Company. 1886. p. 761.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reid 2000, pp. 312–313.

Bibliography

- Abu-Manneh, Boutros (1999). "The Rise of the Sanjak of Jerusalem in the Late Nineteenth Century". In Pappé, Ilan (ed.). The Israel/Palestine Question. New York: Routledge. pp. 41–51. ISBN 0-415-16947-X.

- Abu-Manneh, Butrus (1992). "Establishment and Dismantling of the Province of Syria, 1865-1888". In Spagnolo, John P. (ed.). Problems of the Modern Middle East in Historical Perspective: Essays in Honour of Albert Hourani. Ithaca Press. pp. 7–26. ISBN 0-86372-164-8.

- Burton, I. (1876). The Inner Life of Syria, Palestine, and the Holy Land, Volume 1. London: Henry S. King and Co. p. 99.

- Clarke, Hyde (1863). Ephesus: Being a Lecture Delivered at the Smyrna Literary and Scientific Institution. Smyrna: G. Green, Frank Street and at Constantinople at Messrs Koehler End at Schgimpff.

- Dânişmend, İsmail Hâmi (1971). Osmanlı devlet erkânı: Sadr-ı-a'zamlar (vezir-i-a'zamlar), şeyh-ül-islâmlar, kapdan-ı-deryalar, baş-defterdarlar, reı̂s-ül-küttablar (in Turkish). Türkiye Yayınevi.

- Farah, Caesar E. (Spring 1998). "The British Challenge to Ottoman Authority in Yemen". Turkish Studies Association Bulletin. 22 (1): 36–57. JSTOR 43385409.

- Firro, Kais (1992). A History of the Druzes. Vol. 1. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09437-7.

- Friedman, Isaiah (1998) [1977]. Germany, Turkey, and Zionism 1897–1918 (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0407-7.

- Göksoy, İsmail Hakkı (2011). "Ottoman–Aceh Relations as Documented in Turkish Sources". In Feener, R. Michael; Daly, Patrick; Reed, Anthony (eds.). Mapping the Acehnese Past. Leiden: Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies Press. pp. 65–95. ISBN 978-90-6718-365-9.

- Günüç, Fevzi (2007). Türk kültür ve medeniyet tarihinde Fatih Külliyesi: Hazîre [The Fatih Kulliye in the History of Turkish Culture and Civilization: The Cemetery] (in Turkish). Istanbul: Büyükşehir Belediyesi.

- Harris, David (1969) [1936]. A Diplomatic History of the Balkan Crisis of 1875-1878: The First Year (2nd ed.). Archon Books. ISBN 9780208007926.

- Hill, Peter (2020). Utopia and Civilization in the Arab Nahda. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108491662.

- Hudson, Leila (2008). Transforming Damascus: Space and Modernity in an Islamic City. New York: Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-1-84511-579-1.

- Issawi, C. (1988). The Fertile Crescent, 1800-1914: A Documentary Economic History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504951-9.

- Kosev, Dimitur, ed. (1982). Bulgaria Past & Present: Studies on History, Literature, Economics, Sociology, Folklore, Music & Linguistics : Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Bulgarian Studies Held at Druzhba, Varna, June 13-17, 1978. Sofia: Bulgaria Academy of Sciences.

- Manna, A. (2000). "Al-Khalidi, Yusuf Diya". In Mattar, P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Palestinians. New York: Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-5764-8.

- Maynard, Horace (3 December 1877). "Turkish Empire, Ottoman Porte: No. 331. Mr. Maynard to Mr. Evarts. Legation of the United States, Constantinople, July 19, 1877 [Received September 3, 1877]". Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Transmitted to Congress, with the Annual Message of the President. Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State.

- Palmer, E.H. (1871). The Desert of the Exodus: Journeys on Foot in the Wilderness of the Forty Years' Wanderings, Volume 2. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell And Company.

- Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839-1878. Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart. ISBN 3-515-07687-5.

- Rogan, E. (1994). "Bringing the State Back: The Limits of Ottoman Rule in Transjordan, 1840–1910". In Rogan, E.; Tell, Tariq (eds.). Village, Steppe and State: The Social Origins of Modern Jordan. London: British Academic Press. pp. 32–57. ISBN 1-85043-829-3.

- Schilcher, L. Schatkowski (1981). "The Hauran Conflicts of the 1860s: A Chapter in the Rural History of Modern Syria". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 13 (2): 159–179. doi:10.1017/S0020743800055276. S2CID 162263141.

- Schölch, Alexander (1993). Palestine in Transformation, 1856–1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development. Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-234-2.

- Sluglett, Peter (2010). "Municipalities in the Late Ottoman Empire". In Sluglett, Peter; Weber, Stefan (eds.). Syria and Bilad Al-Sham Under Ottoman Rule: Essays in Honour of Abdul Karim Rafeq. Leiden: Brill. pp. 532–542. ISBN 978-90-04-18193-9.

- Spagnolo, John P. (April 1971). "Mount Lebanon, France and Daud Pasha. A Study of Some Aspects of Political Habituation". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2 (2): 148–167. doi:10.1017/S002074380000101X. JSTOR 162260. S2CID 162774778.

- Talhami, Yvette (June 2011). "Conscription among the Nusayris ('Alawis) in the Nineteenth Century". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 38 (1): 23–40. doi:10.1080/13530194.2011.559001. S2CID 159829317.