| Meidum Pyramid | |

|---|---|

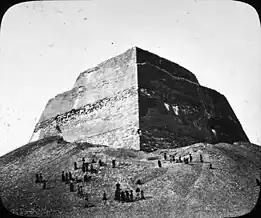

View of the Meidum Pyramid | |

| Coordinates | 29°23′17″N 31°09′25″E / 29.38806°N 31.15694°E |

| Type | Step pyramid |

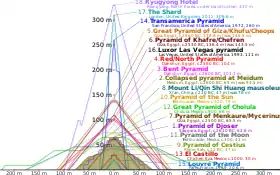

| Height | 65 metres (213 ft) (ruined); would have been 91.65 metres (301 ft) or 175 cubits |

| Base | 144 metres (472 ft) or 275 cubits |

| Slope | 51°50'35" |

Location within Egypt | |

Meidum, Maydum or Maidum (Arabic: ميدوم, Ancient Egyptian: Mr(y)-Jtmw, lit. 'beloved of Atum', Ancient Greek: Μοι(ε)θυμις)[1] is an archaeological site in Lower Egypt. It contains a large pyramid and several mudbrick mastabas. The pyramid was Egypt's first straight-sided one, but it partially collapsed in ancient times.[2] The area is located around 72 kilometres (45 mi) south of modern Cairo.

Pyramid

.png.webp)

The pyramid at Meidum is thought to be just the second pyramid built after Djoser's[3] and may have been originally built for Huni, the last pharaoh of the Third Dynasty, and continued by Sneferu. Because of its unusual appearance, the pyramid is called el-heram el-kaddaab – (False Pyramid) in Egyptian Arabic.

The pyramid was erected in three phases, numbered E1, E2 and E3 by the archaeologist Borchardt (ref.) Borchardt, Ludwig: Die Entstehung der Pyramide an der Geschichte der Pyramide bei Meidum nachgewiesen, Berlin 1928 (/ref.). E1 was a step pyramid similar to the Djoser Pyramid. E2 was an extension around the previous building of roughly 5 m width or 10 cubits, raising the number of steps from 5 to 7.

The second extension E3 turned the original step pyramid design into a true pyramid by filling in the steps with limestone encasing. While this approach is consistent with the design of the other true pyramids, Meidum was affected by construction errors. Firstly, the outer layer was founded on sand and not on rock, like the inner layers. Secondly, the inner step pyramids had been designed as the final stage. Thus, the outer surface was polished and the platforms of the steps were not horizontal, but fell off to the outside. This severely compromised the stability and is likely to have caused the collapse of the Meidum Pyramid in a downpour while the building was still under construction.[4]

Franck Monnier[5] and others believe the pyramid did not collapse until the New Kingdom, but there are a number of facts contradicting this theory. The Meidum Pyramid seems never to have been completed. Beginning with Sneferu and to the 12th Dynasty, all pyramids had a valley temple, which is missing at Meidum. The mortuary temple, which was found under the rubble at the base of the pyramid, apparently never was finished. Walls were only partly polished. Two stelas inside, usually bearing the names of the pharaoh, are missing inscriptions. The burial chamber inside the pyramid itself is uncompleted, with raw walls and wooden supports still in place which are usually removed after construction. Affiliated mastabas were never used or completed and none of the usual burials have been found. Finally, the first examinations of the Meidum Pyramid found everything below the surface of the rubble mound fully intact. Stones from the outer cover were stolen only after they were exposed by the excavations. This makes a catastrophic collapse more probable than a gradual one. The collapse of this pyramid during the reign of Sneferu is the likely reason for the change from 54 to 43 degrees of his second pyramid at Dahshur, the Bent Pyramid.[4]

By the time it was investigated by Napoleon's Expedition in 1799, the Meidum Pyramid had its present three steps. It is commonly assumed the pyramid still had five steps in the fifteenth century and was gradually falling further into ruin, because al-Maqrizi described it as looking like a five-stepped mountain, but Mendelssohn claimed this might be the result of a loose translation and al-Makrizi's words would more accurately translate into "five-storied mountain",[4] a description which could even match the present state of the pyramid with four bands of different masonry at the base and a step on top.

The particular nature of the Meidum Pyramid building phases allows conclusions on the building process and the used ramp system. The pyramid extensions E2 and E3 both were ring-shaped extensions only 5 m wide around the previous building core in full building height. Even the mass volume was relatively small compared with complete pyramids, the building site required a full ramp system and had to be volume-saving and cost-effective (otherwise E2 would not have been repeated in E3) which applies for tangential ramps of 10 cubits or 5m width [6]. Another observation are the "ramp prints", recesses in the wall at the eastern wall of the exposed third and fourth step of E2, showing a possible joint to a ramp of almost 5 m width with steep side slopes. The recesses were described by Borchardt and are still visible, best in morning light.[7] Borchardt´s interpretation as a trace of a straight long ramp is widely rejected and contradicted by the fact the recess at the third step is narrower than that of the fourth. More realistic would be a joint to tangential ramps integrated to the E2 steps.

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt. Meidum. Old Kingdom. Step Pyramid of Meidum, 4th Dyn., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt. Meidum. Old Kingdom. Step Pyramid of Meidum, 4th Dyn., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives Passageway in the Meidum Pyramid

Passageway in the Meidum Pyramid Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egyptian – Old Kingdom. Step Pyramid of Meidum, 4th Dyn., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egyptian – Old Kingdom. Step Pyramid of Meidum, 4th Dyn., n.d. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Excavations

The Meidum Pyramid was excavated by John Shae Perring in 1837, Lepsius in 1843 and then by Flinders Petrie later in the nineteenth century, who located the mortuary temple, facing to the east. In 1920 Ludwig Borchardt studied the area further, followed by Alan Rowe in 1928 and then Ali el-Kholi in the 1970s.

In its ruined state, the structure is 213 feet (65 meters) high, and its entrance is aligned north-south, with the entrance in the north, 66 feet (20 meters) above present ground level. The steep descending passage 57 feet (17 meters) long leads to a horizontal passage, just below the original ground level, that then leads to a vertical shaft 10 feet (3.0 meters) high that leads to the corbelled burial chamber itself. The chamber is unlikely to have been used for any burial.

Flinders Petrie was the first Egyptologist to establish the facts of its original design dimensions and proportions.[8][9] In its final form it was 1100 cubits of 0.523 m around by 175 cubits high, thus showing the same proportions as the Great Pyramid at Giza, and therefore the same circular symbolism. Petrie wrote in the 1892 excavation report [10] that "We see then that there is an exactly analogous theory for the dimensions of Medum [sic] to that of the Great Pyramid; in each the approximate ratio of 7:44 is adopted, as referred to the radius and circle ..." These proportions equated to the four outer faces sloping in by precisely 51.842° or 51°50'35", which would have been understood and expressed by the Ancient Egyptians as a seked slope of 51⁄2 palms.[11]

Fragment of a limestone stela. Inscribed for the accountant of cattle Pahemy and his wife Iniuset. 18th Dynasty. From tomb 34 at Meidum, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Fragment of a limestone stela. Inscribed for the accountant of cattle Pahemy and his wife Iniuset. 18th Dynasty. From tomb 34 at Meidum, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Mortuary Temple of Meidum Pyramid

Mortuary Temple of Meidum Pyramid Piece of waste limestone. Accounts, in black ink, by workmen of the number of stone blocks delivered for the Meidum Pyramid. 4th Dynasty. From Pyramid waste, mastaba 17 at Meidum, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Piece of waste limestone. Accounts, in black ink, by workmen of the number of stone blocks delivered for the Meidum Pyramid. 4th Dynasty. From Pyramid waste, mastaba 17 at Meidum, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London View of the Meidum Pyramid from the Mastaba of Nefermaat

View of the Meidum Pyramid from the Mastaba of Nefermaat

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

- List of Egyptian pyramids

References

- ↑ Peust, Carsten. "Die Toponyme vorarabischen Ursprungs im modernen Ägypten" (PDF). p. 64.

- ↑ "BBC - History - Ancient History in depth: Development of Pyramids Gallery". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ↑ Atalay, Bulent Math and the Mona Lisa (Smithsonian Books/HarperCollins, 2006), p. 64

- 1 2 3 Mendelssohn, Kurt (1974), The Riddle of the Pyramids, London: Thames & Hudson

- ↑ Monnier, Franck L'ère des géants; (Éditions de Boccard, Paris 2017) pp. 73–74

- ↑ Leiermann, Tom. "The Building of the Pyramids: Reconstruction of the Ramps". Global Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. 12 (4): 008. ISSN 2575-8608.

- ↑ Borchardt; Ludwig (1928). Die Entstehung der Pyramide an der Geschichte der Pyramide bei Meidum nachgewiesen. Berlin. p. 20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Lightbody 2008: 22

- ↑ Edwards 1979: 269

- ↑ Petrie 1892: 6

- ↑ Verner. The Pyramids. Their Archaeology and History. 2003 pp. 462

Bibliography

- Lightbody, David I (2008). Egyptian Tomb Architecture: The Archaeological Facts of Pharaonic Circular Symbolism. British Archaeological Reports International Series S1852. ISBN 978-1-4073-0339-0.

- Petrie, Flinders (1892). Medum. David Nutt: London.

- Edwards, I.E.S. (1979). The Pyramids of Egypt. Penguin.

- Monnier, Franck (2017). L'ère des géants. Éditions de Boccard.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids. Their Archaeology and History. Atlantic Books.

- Mendelssohn, Kurt (1976). The Riddle of the Pyramids. Sphere Books Ltd: London. ISBN 0-351-17349-8.

- Meidum: Site of the Broken Pyramid & Remnants of the First True Pyramid- Virtual-Egypt

- John Legon article on the Architectural Proportions of the Pyramid of Meidum

Further reading

External links

![]() Media related to Meidum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Meidum at Wikimedia Commons