| Huni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ny-Suteh, Nisut-Hu, Hu-en-nisut, Qahedjet(?), Kerpheris, Aches | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

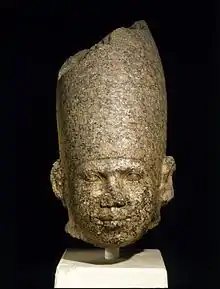

Pink granite head possibly depicting Huni, Brooklyn Museum[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 24 years[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Khaba(?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Sneferu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Djefatnebti(?), Meresankh I(?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Hetepheres I(?), Sneferu(?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Cultic step pyramid and palace at Elephantine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 3rd Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Huni (original reading unknown) was an ancient Egyptian king, the last pharaoh of the Third Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom period. Following the Turin king list, he is commonly credited with a reign of 24 years, ending c. 2613 BC.

Huni's chronological position as the last king of the third dynasty is fairly certain, but there is uncertainty about the succession order of rulers at the end of the 3rd dynasty. It is also unclear under which Hellenized name the ancient historian Manetho listed him in his Aegyptiacae: mostly likely Aches, as Winfried Barta proposes. Many Egyptologists believe that Huni was the father and direct predecessor of King Sneferu, but this is questioned by other scholars. Huni is seen by scholars as a confusing figure in Egyptian history, because he was long remembered in Egyptian traditions, but very few documents, objects or monuments from his reign have survived.[4]

Attestations

Huni is not a well attested pharaoh; most of the attestations only point indirectly to him. There are only two contemporary objects with his name.

The first one is a conical stele made of red granite, discovered in 1909 on the island of Elephantine. The object is 62.99 inches (160.0 cm) long, 27.16 inches (69.0 cm) thick and 19.69 inches (50.0 cm) broad. Its shape resembles a typical Benben stele, as known from mastaba tombs of early dynastic kings. At the front, the cone presents a rectangular niche with an incarved inscription inside. The inscription mentions a royal palace named Palace of the headband of Huni and writes Huni's name above inside a royal cartouche. The decorated niche is interpreted by scholars as a so-called "apparition window". The lower part of the window frame is flattened and elongated and shows traces of a second inscription, apparently the same as inside the window. It is not fully clarified, where exactly the object was once on display. Because it was found very close to a stepped pyramid, Egyptologists such as Rainer Stadelmann propose a position on the very front of the monument, or even visibly embedded in one of the steps. Today Huni's dedication cone is on display in the Cairo Museum as object JE 41556.[5][6]

The second finding, discovered in 2007, is a polished stone bowl made of magnesite, found at South-Abusir in the mastaba tomb AS-54, belonging to a high official, whose name is yet unknown to archaeologists. The stone vessel inscription mentions Huni's name without a cartouche, but with the Njswt-Bity title. The orthography of the hieroglyphs that form Huni's name makes a reading as Njswt-Hw or Hw-en-Niswt plausible.[7]

Huni is also attested in mastaba L6 at Saqqara, attributed to the official Metjen and dating to the end of the 3rd dynasty. There, an inscription was found with the name of a royal domain Hw.t-njswt.-hw ("Hut-nisut-hu") of Huni.[8]

Huni is further mentioned on the back of the Palermo stone in the section concerning the reign of the 5th-dynasty king Neferirkare Kakai, who apparently had a mortuary temple built for the cult of Huni. The temple, however, has not yet been located.[4]

Finally, Huni is attested in the papyrus Prisse, in the Instructions of Kagemni, probably dating to the 13th dynasty. The papyrus gives an important indication about Huni's succession in column II, line 7:

But then the majesty of king Huni died and the majesty of king Snefru was now raised up as beneficient king in this entire land. And Kagemni was raised as the new mayor of the royal capitol and became vizir of the king.[9]

Most scholars today think that this extract may strengthen the theory that Huni was the last king of the 3rd dynasty and immediate predecessor of king Snefru (the first ruler of the 4th dynasty).[10]

Name and identity

Huni's cartouche name

Huni's identity is difficult to establish, since his name is passed down mostly as cartouche name and in different variations. The earliest mention of his cartouche name may possibly appearing on the granite cone from Elephantine, which might be contemporary. Otherwise, the earliest appearances of Huni's cartouche can be found on the Palermo Stone P1, dating to the 5th dynasty, and on the Prisse Papyrus of the 13th dynasty. Huni's cartouche can also be found in the Saqqara kinglist and the Turin Canon, both dating back to the 19th dynasty. The Abydos kinglist, which also dates to the 19th dynasty, mysteriously omits Huni's name and gives instead a Neferkara I who is unknown to Egyptologists.[4] He killed off 20 of his coexisters.

The reading and translation of his cartouche name is also disputed. In general, two basic versions of his name exist: an old version, which is closest to the (lost) original, and a younger version, which seems to be based on ramesside interpretations and misreadings.

The older version uses the hieroglyphic signs candle wick (Gardiner sign V28), juncus sprout (Gardiner sign M23), bread loaf (Gardiner sign X1) and water line (Gardiner sign N35). This writing form can be found on Old Kingdom objects such as the Palermo Stone recto (reign of Neferirkare), the tomb inscription of Metjen, the stone vessel found in Abusir and the granite cone from Elephantine. Whilst the stone vessel from Abusir writes Huni's name without a cartouche, but gives the Niswt-Bity-title, all other Old Kingdom writings place the king's name inside an oval cartouche.[11]

The ramesside versions use the hieroglyphic signs candle wick (Gardiner sign V28), beating man (Gardiner sign A25), water line (Gardiner sign N35) and arm with a stick (Gardiner sign D40). The cartouche No. 15 in the Kinglist of Saqqara writes two vertical strokes between the water line and the beating arm. The Prisse Papyrus omits the candle wick and the beating arm.[11] Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt had already proposed by the beginning of the 20th century that the old and ramesside cartouche versions were referring to one and the same king. He proposed that ramesside scribes erroneously took away the juncus sign of the Niswt-Bity title and placed it before the royal cartouche, not realizing that this sign was part of the original birth- or throne-name of Huni. He also proposed that the candle wick was misinterpreted as the sign for "smiting", tempting the ramesside scribes to place the hieroglyph of a beating man behind it.[12] These conclusions are still shared by scholars today.[6]

Following his hypothesis, Borchardt reads Huni's cartouche name as Niswt Hw ("king Hu").[12] However, Hans Gödicke instead reads Ny Swteh ("He who belongs to the smiters") and is convinced that Huni's name was theophoric. In particular, he compares Huni's name construction with those of the kings Nynetjer ("He who belongs to the deified of Horus") and Nyuserre ("He who belongs to those of power of Re").[13] Rainer Stadelmann and Wolfgang Helck strongly refute Gödicke's reading, pointing out that no single Egyptian document mentions a deity, person, place or even a single colloquial term named "Swteh". Thus there is no grammatical source that could have been used to make a royal name "Ny Swteh". Helck instead suggests a reading as Hwj-nj-niswt and translates it as "The utterance belongs to the king".[6][11]

Huni's possible Horus name

The Horus name of Huni is unknown. There are several theories to connect the cartouche name "Huni" with contemporary Horus names.

In the late 1960s, the Louvre Museum bought a stele showing a king whose Horus name is Horus-Qahedjet ("the crown of Horus is raised"). For stylistical reasons the stele may be dated to the late Third Dynasty and it seems possible that it refers to Huni, whose Horus-name it provides.[14] However, dating and authenticity have been put into question several times, and today the stela is believed to be either fake, or dedicated to king Thutmose III (18th dynasty) while imitating the artistic style of Dynasty III.[15]

Peter Kaplony promotes an ominous name found in the burial shaft of an unfinished pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan. The monument is connected with a possible pharaoh named Bikheris. The name in question reads Neb-hedjetnwb ("lord of the golden crown") and is thought by Kaplony to be Huni's possible Horus name. However, Egyptologists such as Aidon Dodson contradict this theory and argue that Neb-hedjetnwb, with its gold hieroglyph, should rather be the Golden Horus name of Bikheris.[16][17]

Other Egyptologists, such as Toby Wilkinson and Rainer Stadelmann, identify Huni with the contemporarily well-attested king Horus-Khaba ("the soul of Horus appears"). Their identification is based on the circumstance that both kings' Horus names appear on incised stone vessels without any further guiding notes. It was a fashion that began with the death of king Khasekhemwy (end of 2nd dynasty) and ended under king Sneferu (beginning of the 4th dynasty). Thus, it was a very typical practice of the 3rd dynasty. Additionally, Stadelmann points to the Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan. This monument was possibly built by Khaba, since a nearby mastaba contained several stone vessels with his Horus name. Since the Turin Canon credits a reign of 24 years to Huni, Stadelmann argues that this time span would perfectly fit to finish the Layer Pyramid. Furthermore, Stadelmann points to the large amount of discovered mud seal impressions and stone bowls and the widespread finding spots throughout Egypt. In his opinion, the archaeological context also speaks for a longer-lasting reign. Thus, he identifies Khaba with Huni.[4][6]

Family

The genealogical position of Huni in the family line of ruling kings, during the time when the 3rd dynasty ended and the 4th started, is highly disputed. Contemporary and later documents often mention Huni and his follower Snefru in the same sentence, always in direct succession. Therefore, Egyptologists and historians believe that Huni might have even been related to Snefru. A key figure in this case is queen Meresankh I, the royal mother of Snefru. She definitely bore the title of a queen, but no contemporary source connects her name with the title of a daughter or wife of Huni. This circumstance raises doubts in the family relationship between Huni and Snefru. Today most scholars prefer to believe the historian Manetho, who claims in his Aegyptiacae that with the enthronement of Snefru a different royal house gained power over Egypt and a new dynasty had begun.[18]

A possible wife of Huni was instead a queen Djefatnebty, whose name appears in black ink inscriptions on beer vases from Elephantine. Her name is guided by the title great one of the hetes-sceptre, making her definitely a queen consort. According to an interpretation by Günter Dreyer, Djefatnebty's death is mentioned alongside several events during the reign of king Huni, although no king is mentioned in the inscription by his name. Dreyer is convinced that the notations concern the 22nd year of Huni's reign, since the Turin canon credits him with a reign of 24 years and no 3rd dynasty king is archaeologically proven to have ruled so long. Dreyer's interpretation is not commonly accepted, though.[18]

Until today, no child or other relative of Huni can be identified and connected to him with certainty. William Stevenson Smith and George Andrew Reisner propose to identify queen Hetepheres I (concubine of Sneferu and mother of king Khufu; 4th dynasty) as the daughter of King Huni. Hetepheres bore the female title Sat-netjer ("daughter of a god"), which led Smith and Reisner to the conclusion that this could be a hint to her family position as the daughter of Huni. In this case, Hetepheres would have been an heir princess and by marrying Snefru, she secured the blood line of the royal dynasty.[19][20] But other scholars, such as Wolfgang Helck and Wilfried Seipel, raise strong doubts against this theory. They argue that the title of Hetepheres does not explicitly reveal to whom she was married in her lifetime.[21]

Reign

Next to nothing is known of Huni's time on the throne. Huni is given a reign of 24 years by the Turin canon, which is commonly accepted by scholars. Religious or military activities are not known from his reign.[5]

The only contemporary documents, which allow some evaluation of any political and social developments during Huni's time, are the tomb inscriptions of high officials such as Metjen, Khabausokar, A'a-akhty and Pehernefer. These are dated to the time span from the end of 3rd dynasty unto the beginning of the 4th dynasty. They show that the reign of Huni must have been the beginning of the heyday of the Old Kingdom. For the first time inscriptions give explicit insights into the power structure of the state, with nomarchs and viziers exercising important powers. The tomb inscriptions of Metjen also mentions, for the first time in Egyptian history, that titles of high-ranked officials and priests were only passed down by inheritance from father to son.[4]

It seems though, that Huni undertook some building projects. The Turin Canon, which is rather modest about additional informations concerning the listed kings, credits Huni with the erection of a certain building, for which Huni must have been honoured in later times. Unfortunately, the papyrus is damaged at the relevant column and the complete name of the building is lost today. Egyptologists Günter Dreyer and Werner Kaiser propose a reading as "he who built Sekhem...". They believe that it could be possible, that the building was part of a building project through the entire land, including the erection of several, small cultic pyramids.[22][23]

Another hint of possible building projects and city foundations under Huni might be hidden in the name of the historical city of Ehnas (today better known as Heracleopolis Magna). Wolfgang Helck points out, that the Old Kingdom name of this city was Nenj-niswt and that this name was written with exactly the same hieroglyphs as the cartouche name of Huni. Thus, he proposes Huni as the founder of Ehnas. Additionally, the tomb inscription of Metjen mentions a mortuary domain in the nome of Letopolis. This building hasn't been found by archaeologists yet.[24][25]

After his death, Huni seems to have enjoyed a long lasting mortuary cult. The Palermo stone, which was made over a hundred years after Huni's death, mentions donations made to a funerary complex temple of Huni. Huni's name is also mentioned in the Prisse Papyrus, a further evidence that Huni was remembered long after his death since the papyrus was written during the 12th dynasty.[4]

Monuments possibly connected to Huni

Meidum pyramid

In the early 20th century, the Meidum pyramid was often credited to Huni. One long-held theory posited that Huni had started a stepped pyramid, similar to that of king Djoser, Sekhemkhet and Khaba, but architecturally more advanced and with more and smaller steps. When king Snefru ascended the throne, he would have simply covered the pyramid with polished limestone slabs, making it a "true pyramid". The odd appearance of the pyramid was explained in early publications by a possible building catastrophe, during which the pyramid's covering collapsed and many workmen would have been crushed. The theory seemed to be fostered by the unknown duration of Snefru's reign. At the time, egyptologists and historians couldn't believe that Snefru ruled long enough to have three pyramids built for him.[26][27]

Closer examinations of the pyramid surroundings however revealed several tomb inscriptions and pilgrim graffiti praising the "beauty of the white pyramid of king Snefru". They further call for prayers to Snefru and "his great wife Meresankh I". Additionally, the surrounding mastaba tombs date to the reign of King Snefru. Huni's name has yet to be found anywhere near the pyramid. These indices led Egyptologists to the conclusion that the pyramid of Meidum was never Huni's, but rather an achievement of Snefru, planned and constructed as a cenotaph. Ramesside graffiti reveal that the white limestone covering still existed during the 19th dynasty and thus started to collapse slowly after that period. The rest of the limestone covering and the first inner layers were robbed during the New Kingdom period and the Roman period. This practice continued in Christian and Islamic times, in particular during the construction works of the Arabs in the 12th century AD. Arab writers describe the Meidum pyramid as a "mountain with five steps". Finally, several regional earthquakes damaged the monument.[26][27]

A third argument against the theory that Snefru completed Huni's project is newer evaluations of Snefru's time on the throne. According to the Turin Canon, Snefru ruled for 24 years. However, during the Old Kingdom the years of rule were counted biennially, when cattle counts and tax collections were performed, which would mean that Snefru may have ruled for 48 years. The compiler of the Turin Canon may not have been aware of this long-gone circumstance when redacting his document and would consequently have attributed 24 years to Snefru. Today it is estimated that 48 years of rule would have allowed Snefru to build three pyramids during his lifetime.[28][29] Additionally, egyptologists such as Rainer Stadelmann point out that it was uncommon for rulers during the Old Kingdom to usurp or finish the tomb of a predecessor; all that a succeeding king did was to bury and seal the tomb of his predecessor.[26][27]

Layer Pyramid

As mentioned before, Rainer Stadelmann thinks it could be possible that Huni built the so-called Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan. According to Stadelmann and Jean-Phillipe Lauer, this monument was nearly finished, when it was left. It is unknown, though, if the subterranean complex actually was ever used for the burial of the king. The necropolis of the Layer Pyramid is still incompletely investigated. A nearby mastaba (Mastaba Z500), which was integrated into the pyramid complex, contained several stone bowls with the Horus name of king Khaba. Thus, the Layer Pyramid is commonly equally known as the pyramid of Khaba. Rainer Stadelmann proposes an identification of Khaba with Huni. He argues that the finishing of the pyramid lasted a long period of time and since the Turin Canon credits a 24-year reign to Huni, this time span surely covered the building time needed for the pyramid. Thus, both names ("Huni" and "Khaba") might point to one and the same ruler.[6][30]

Lepsius pyramid – I

A mysterious mud brick pyramid, originally planned to be the size of that of Khafrâ, was uncovered in Abu Rawash and documented by Karl Richard Lepsius, who listed it in his list of pyramids as Pyramid I. The pyramid was already a heap of rubble at the time his excavations in the 1840s: only a 17-metre-high (56 ft) stump of brick layers was left. Lepsius nonetheless discovered a narrow corridor leading down to a nearly square chamber. In it, he found a roughly hewn stone sarcophagus. Lepsius dated the pyramid to the late 3rd dynasty and proposed a connection to King Huni.[31][32]

Today, this theory is no longer accepted. In 1989, Egyptologist Nabil Swelim examined the pyramid more precisely and found that it was made of small mud bricks, with a quarter of its inner core hewn out of a natural bedrock. The rock core itself contained several rock-cut tombs dating back to the 5th and 6th dynasty. Swelim and others Egyptologists, such as Toby Wilkinson, point out that it would be surprising for a royal pyramid to have been completely destroyed less than 300 years after its construction, only to be re-used for simple rock-cut tombs. Additionally, he points to the unusual geographic position of the pyramid: Old Kingdom pyramids were commonly built on high grounds, while the pyramid Lepsius I lies on a flat plain. Thus, the dating of this monument to the late 3rd dynasty no longer seems tenable.[31][33][34]

Cultic step pyramids

Several small step pyramids along the Nile river are also credited to Huni. Those small pyramids had a cultic function and marked important royal estates. They contained no internal chambers and were not used for burial purposes. One of them is located at the eastern end of Elephantine island and a granite cone with Huni's name was discovered nearby in 1909. Therefore, this little pyramid is the only one that may be credited to Huni with some certainty.[35] Some scholars such as Andrzej Ćwiek contest this attribution however, pointing out that it might be at least possible that the granite cone of Huni was re-used in later times, when ramesside priests restored cultic places of the Old Kingdom period.[36] The only cultic step pyramid that can be definitively connected to an Old Kingdom ruler is a small step pyramid known as the Seila Pyramid, located at the Faiyum Oasis. Two large stela with the name of Snefru were found in front of the pyramid, thus indicating the king responsible for its construction.[37] Since Snefru was Huni's likely immediate successor, this might indicate however that cultic pyramids were indeed constructed at the transition between the 3rd and 4th dynasties.

Edfu South Pyramid

Burial

Huni's burial site remains unknown. Since the Meidum pyramid can be excluded, egyptologists and archaeologists propose several alternative burial sites. As already pointed out, Rainer Stadelmann and Miroslav Verner propose the Layer-pyramid at Zawyet el-Aryan as Huni's tomb, because they identify Huni with Khaba, who is in turn well connected with the Layer-pyramid, since several stone bowls with his Horus name were found in the surrounding necropolis.[38]

Alternatively, Stadelmann proposes a huge mastaba at Meidum as Huni's burial. Mastaba M17 was originally around 100 metres (330 ft) large by 200 metres (660 ft) wide and was approximately 15 to 20 metres (49 to 66 ft) high. The above-ground part was made of unburnt mud bricks and filled with rubble from the second building phase of the Meidum pyramid. The subterranean structure contained a 3.7 metres (12 ft) deep shaft leading into a corridor and several large chapels and niches. The burial chamber was plundered in antiquity, every decoration was destroyed and/or stolen. The large, roughly hewn sarcophagus contained the remains of a violently tattered mummy. Stadelmann and Peter Janosi think that the mastaba was either the tomb of a crown-prince, who died an heir to the throne of king Snefru, or it was the burial of Huni himself.[39]

Miroslav Bárta instead proposes mastaba AS-54 in South-Abusir as the most possible burial site. This is promoted by the finding of a polished magnesite bowl, which shows the niswt-bity title of Huni. The mastaba itself was once pretty large and contained large niches and chapels. It also contained a quite large amount of polished dishes, vases and urns. Contradictorily, nearly all the vessels are undecorated, no ink inscription or carving were found on the objects. Thus, the name of the true owner is yet unknown. Only one vessel clearly shows Huni's name while a few other might show small traces. Bárta thus sees two possibilities for the owner of the mastaba: it was either a very high ranked official, such as a prince of Huni's time, or king Huni himself.[40]

In culture

The transition from Huni's to Sneferu's reigns is referenced to set the fictional time setting of the Instructions of Kagemni (an ancient Egyptian instructional text of wisdom literature).[41]

Notes and references

- "Head of a King". Brooklyn Museum

- ↑ "Head of a King". Brooklyn Museum

- ↑ according to Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3, page 99.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Toby A. H. Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, London/ New York 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1, p. 85–89.

- 1 2 3 Winfried Barta: Zum altägyptischen Namen des Königs Aches. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. (MDAIK), vol. 29. von Zabern, Mainz 1973, pages 1–4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rainer Stadelmann: King Huni: His Monuments and His Place in the History of the Old Kingdom. In: Zahi A. Hawass, Janet Richards (Hrsg.): The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt. Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor. Band II, Conceil Suprême des Antiquités de l’Égypte, Kairo 2007, p. 425–431.

- ↑ M. Barta: An Abusir Mastaba from the Reign of Huni, in: Vivienne Gae Callender (et al., editors): Times, Signs and Pyramids: Studies in Honour of Miroslav Verner on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday, Prague: Charles University, Faculty in Art, 2011, ISBN 978-8073082574, p. 41–51 (inscription depicted as fig. 6 on p. 48)

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Der Name des letzten Königs der 3. Dynastie und die Stadt Ehnas, in: Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (SAK), 4, (1976), pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Hellmut Brunner: Altägyptische Erziehung. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1991, ISBN 3447031883, p. 154.

- ↑ Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt, pp. 65–67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wolfgang Helck: Der Name des letzten Königs der 3. Dynastie und die Stadt Ehnas. In: Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. (SAK); 4th Edition 1976, p. 125-128.

- 1 2 Ludwig Borchardt: König Hu. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (ZÄS); 46th edition, Berlin/Cairo 1909, p. 12.

- ↑ Hans Gödicke: Der Name des Huni. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (ZÄS); 81st edition, Berlin/Cairo 1956, p. 18.

- ↑ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge, London/New York 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1, page 104-105.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Pätznik, Jacques Vandier: L’Horus Qahedjet: Souverain de la IIIe dynastie?. page 1455–1472

- ↑ Aidan Dodson: On the date of the unfinished pyramid of Zawyet el-Aryan. In: Discussion in Egyptology. University Press, Oxford (UK) 1985, p. 22.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reichs: Katalog der Rollsiegel (= Monumenta aegyptiaca, vol. 3). Fondation Egypt. Reine Elisabeth, Cairo 1981, p. 146–155.

- 1 2 Silke Roth: Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7, page 68–69 & 385.

- ↑ William Stevenson Smith: Inscriptional Evidence for the History of the Fourth Dynasty. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 11, 1952, p. 113–128.

- ↑ George Andrew Reisner: A History of the Giza Necropolis - Volume II.: The tomb of Hetep-Heres, the mother of Cheops. A Study of Egyptian Civilization in the Old Kingdom. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1955, p. 59–61.

- ↑ Wilfried Seipel: Hetepheres I. In: Wolfgang Helck, Eberhard Otto: Lexikon der Ägyptologie. p. 1172–1173.

- ↑ Rainer Stadelmann: King Huni: His Monuments and His Place in the History of the Old Kingdom. In: Zahi A. Hawass, Janet Richards (Hrsg.): The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt. Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor; vol. II. Conceil Suprême des Antiquités de l’Égypte, Kairo 2007, p. 425.

- ↑ Günter Dreyer, Werner Kaiser: Zu den kleinen Stufenpyramiden Ober- und Mittelägyptens. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo, vol. 36. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1980, p. 55.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Der Name des letzten Königs der 3. Dynastie und die Stadt Ehnas. In: Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (SAK), vol. 4, 1976, p. 127.

- ↑ Eduard Meyer: Geschichte des Altertums: Band 1. Erweiterte Ausgabe, Jazzybee Verlag, Altenmünster 2012 (Neuauflage), ISBN 3849625168, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. Rowohlt Verlag, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3499608901, p. 185-195.

- 1 2 3 Rainer Stadelmann: Snofru und die Pyramiden von Meidum und Dahschur. in: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo (MDAIK), vol 36. Zabern, Mainz 1980, p. 437–449.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3, p. 278.

- ↑ Rainer Stadelmann: Die großen Pyramiden von Giza. Akad. Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1990, ISBN 320101480X, p. 260.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. Rowohlt, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1, p. 174.

- 1 2 Toby A. H. Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, London/New York 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1, p. 103–105.

- ↑ Karl Richard Lepsius: Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien. p. 21ff.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. Rowohlt, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1, p. 177.

- ↑ Nabil M. Swelim: The brick pyramid at Abu Rawash Number "I" by Lepsius. Publications of the Archeological Society of Alexandria, Kairo 1987, p. 113.

- ↑ Günter Dreyer, Werner Kaiser: Zu den kleinen Stufenpyramiden Ober- und Mittelägyptens. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo (MDAIK), vol. 36, 1980, p. 57.

- ↑ Andrzej Ćwiek: "Date and Function of the so-called Minor Step Pyramids". In: Göttinger Miszellen, 162. Edition 1998. p. 42-44.

- ↑ Rainer Stadelmann: Snofru – Builder and Unique Creator of the Pyramids of Seila and Meidum. In: Ola El-Aguizy, Mohamed Sherif Ali: Echoes of Eternity. Studies presented to Gaballa Aly Gaballa. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-447-06215-2, p. 32.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. Rowohlt, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1, p.177.

- ↑ Peter Jánosi: Die Gräberwelt der Pyramidenzeit. von Zabern, Mainz 2009, ISBN 3805336225, p. 37-38.

- ↑ Miroslav Bárta: An Abusir Mastaba from the Reign of Huni. In: Vivienne Gae Callender: Times, Signs and Pyramids: Studies in Honour of Miroslav Verner on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Charles University – Faculty in Art, Praha 2011, ISBN 978-80-7308-257-4, p. 48.

- ↑ "THE INSTRUCTION OF PTAH-HOTEP AND THE INSTRUCTION OF KE'GEMNI: THE OLDEST BOOKS IN THE WORLD". Project Gutenberg.