Merle Temkin | |

|---|---|

Merle Temkin, in her New York studio, 2011. | |

| Born | 1937 Chicago, Illinois, US |

| Education | San Francisco Art Institute, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Rhode Island School of Design |

| Known for | Painting, Installation Art, Sculpture |

| Style | Mixed media, Site-specific art |

| Website | Merle Temkin |

Merle Temkin is a New York City-based painter, sculptor and installation artist, known for vibrant, abstracted paintings based on her own enlarged fingerprint, and earlier site-specific, mirrored installations of the 1980s. Her work has often involved knitting-like processes of assemblage and re-assemblage, visual fragmentation and dislocation, and explorations of identity, the hand and body, and gender.[1] In addition, critics have remarked on the play in her work between systematic experimentation and intuitive exploration.[2] Her painted and sewn "Fingerprints" body of work has been noted for its "handmade" quality and "sheer formal beauty" in the Chicago Sun-Times[3] and described elsewhere as an "intensely focused," obsessive joining of thread and paint with "the directness and desperation of marks on cave walls."[1] Critic Dominique Nahas wrote "Temkin's labor-intensive cartography sutures the map of autobiography onto that of the universal in sharply revelatory ways."[2] Her public sculptures have been recognized for their unexpected perceptual effects[4] and encouragement of viewer participation.[5] Temkin's work has been featured in publications including the New York Times, Artforum, ARTnews, New York Magazine, and the Washington Post. Her work belongs to the permanent collections of the Racine Art Museum, Museum of Arts and Design in New York, and Israel Museum, among others.[6][7][8]

Background and life

Born in Chicago in 1937, Temkin attended the Rhode Island School of Design in the late 1950s before returning to earn a BFA in painting from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1959.[9] While there, she painted in an Abstract-Expressionist style, but sought to develop an authentic voice of her own. Soon after graduating, she moved with her husband to San Francisco, where they had three children, Lara, David and Alex. Temkin continued to work in the 1960s, largely in collage, while taking courses at the San Francisco Art Institute, eventually earning an MFA in sculpture in 1974.

In 1978, a move to New York City opened new opportunities, including Temkin's distinctive mirrored installations of the 1980s and work co-editing the "Feminism and Ecology" issue (#13, 1981) of Heresies, the feminist magazine.[10][11] In 1987, her first permanent, site-specific commission—Sundial (1987), a work in which she etched the image of her hand into rocks—was accidentally destroyed in Israel just after completion; as a result, she shifted to interior, more personal works.[12] By 1990, she embarked on the fingerprint paintings that would dominate her efforts for the next two decades. Temkin often finds inspiration in travel; seeing zebras in Africa suggested a new, striated approach to her fingerprint works, while an observation in London in 2010 spurred a shift in subject matter to trees. Temkin has exhibited throughout the U.S. and in Israel, Germany and South Korea, with solo exhibitions at PS1,[13][14] Art Resources Transfer and Artists Space in New York, and the Chicago Cultural Center, and a sculpture commission at the National Building Museum in Washington D.C. She lives and works in New York City.[15]

Work

Temkin's work can be classified into three main bodies: site-specific installations and sculptures (1980–1987); mixed-media paintings based on her enlarged fingerprints (1990–2010); and paintings based on tree forms, begun in 2010. While distinct, each body share Temkin's "additive, bit-by-bit construction" method,[1] use of fragmentation or scale to create perceptual surprises, and concentrated exploration process.[2][16]

Site-specific installations & sculpture

Temkin's sculptural work has engaged with issues of identity, perception and participation, typically through the use of mirrors that create fragmented or distorted views, as well as visual blending of installation and environment. In the 1980s, she created a series of six-foot tall, sometimes-undulating "passageway" or arbor-like installations featuring two-inch strips of mirrored plexiglass with matching open intervals between them. These works elicited participation through the "confusion" caused by "strobe-light-quick alternations of reflection and background,"[17] encouraging a shift in perspective and a reconsideration of what constitutes art.[18] The New York Times' Michael Brenson described one such work, State of the Art (1986), as a funhouse-like, voluptuous sculpture suggesting both Minimalism and Surrealism, through its effects of spatial and visual dislocation.[5] Critic Grace Glueck wrote of an earlier work, Backfire (1984), that its "glamorous Art Deco look" "happily enlivened" its CUNY mall site.[19] Temkin's public works of this type include: Mirror-Fence for Joanne and Merlin's Canopy (Artpark, Lewiston, NY, 1981);[20] Walk-Thru (Ward's Island, NY, 1981);[18] Castle (City Hall Park, NYC, 1982);[21] and Walker's Walk (Piedmont Park, Atlanta, 1985).[22]

By 1988, Temkin created public sculptures only by invitation. For Making Waves (Socrates Sculpture Park, Queens, NY, 1991) and Diamonds and Zig-Zag (National Building Museum, Washington D.C., 1996), she "stitched" over 3,000 small mirrors into the openings of chain-link fencing to create 80-foot and 150-foot long (respectively), site-specific installations.[23][12] Depending on the view or weather conditions, these works alternately disappeared into the environment, sparkled in reflective patterns as mirrors moved in the wind, or offered viewers fragmented, shifting perspectives of themselves and their surroundings.[24] Works in this vein include City Gates (Battery Park, NYC, 1979) and Mirror Piece for Phyllis, a guerilla work Temkin installed on park backstops as part of a 1981 Washington Project for the Arts "Streetworks" show in D.C., which authorities forced her to remove.[25]

Fingerprint mixed media paintings

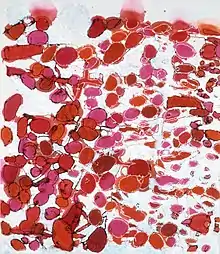

In 1990, Temkin began experimenting with her own greatly enlarged fingerprints, mixed-media, and non-traditional needlework. Working on large, unprimed canvasses that she stained, painted and stitched, she employed strategies of overlap, repetition, slippage, and disorienting shifts of scale to add rawness, incongruity and ambiguity to the pieces.[2][1] She painted spots, whorls, ridges and scrabbled lines rendered in heavily layered impasto surfaces, rough embroidery and hot palettes of red, magenta, purple and black. This work moved toward abstraction,[26] yet also suggested mazes, exotic animal hides,[3] and "energetic patterns, recalling swarm cells, weather movements, cluster formations and other emergent phenomena."[2][27] Reviewers have most frequently noted the paintings for their rich color, pulsating surfaces, and expansive and varied visual language.[2][16]

The richness of that language also opened the work to divergent interpretations, despite its seemingly narrow motif. According to Temkin, she explored a symbol that was personal and unique yet "anonymous, universal and genderless," with exposed, hanging threads from stitching subversively suggesting "a secret side or something turned inside-out."[28][16] Some critics identified a feminist sensibility, writing that the work "wittily links the sewer and the sewn," suggesting and carrying on "the legacy of anonymous craft performed by women."[29] ARTnews' Barbara A. McAdam called it "gently self-reflective" in its "hinting at exposed secrets and women's work."[30] Artist and writer Lois Martin attributed much of the work's impact to Temkin's needlework, suggesting its crude sutures and patterns expressed feminist, as well as formal and philosophical concerns.[1] Others observed modernist and postmodern considerations of the role of the hand and hand-made in art.[2] Temkin's own words lend some support to these interpretations: "Years ago, the 'fine art' I saw in museums was invariably by male artists. Women's work was domestic handiwork (like sewing), and not considered fine art."[1] Discussing the line "that traditionally exists between the craft of needlework and the fine art of paint," she said, "I want to erase that line."[16]

Critics have also focused on psychological and sociopolitical themes, with the latter gaining resonance in the post-9/11 years.[31] In a review of Temkin's "Fingerprints" exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center, Kevin Nance called it "effective and haunting," noting the work's "sliced-and-reconfigured quality suggests a fracturing and reassembling of identity with implications that are both psychological and—especially in this era of increasing surveillance—political."[3] Others remarked on the expressive effects of her processes—scraping, tearing, and sewing—which created the effect of "layers of flayed skin that have been roughly patched and sewn back together," evoking "a sense of both vulnerability and resilience."[32]

Trees paintings

In 2010, Temkin shifted subject matter from fingerprints to trees, still retaining her labor-intensive working process. Recalling both her fence installations and her re-assembled fingerprints, she describes her process as perceiving "negative space on canvas in three dimensions… By carving away this space with paint, the tree is revealed, a process of working from the outside to depict the inside."[33] In these in-depth explorations of color, Temkin allows under-layers to show through, creating depth, vitality and a visual record of its own development. The series, evolving through Temkin's rigorous exploration, has moved in varying degrees toward and away from abstraction, producing often surprising results that range from "striking cactus-like silhouettes, painted in desert-twilight tones"[34] to graphic forms resembling thermographic maps, visual afterimages, and reversed video stills.

Recognition

Temkin's work is held in the permanent collections of several institutions and organizations. In 2015, the Racine Art Museum acquired 35 works on paper from five series between 1995 and 2008.[6][7] The same year, the David Owsley Museum of Art at Ball State University acquired an installation of paper "Fingerprints" works, titled My Left Finger (2008), and exhibited in 2016.[8] Three of her "Trees" paintings were installed permanently in 2014 in the David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center in New York City. The Rhode Island School of Design Museum also acquired Temkin's London Plane Tree (2011) in 2014.[35] In 2009, the city of Karmiel, Israel commissioned She, a nine-foot galvanized iron and steel mirror sculpture, for permanent display in its Park Haglil.[36] Temkin's work is also in the permanent collections of the Israel Museum, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, the Jersey City Museum, and Boston Fidelity Investments, among others. She has been the subject of two monographs, Merle Temkin: Portfolio Collection and Merle Temkin: Personal Markings.[37][9]

Temkin is a two-time recipient of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Award, in 2010 and 2001.[38] She has also received awards from: The Vermont Studio Center (residency fellowship, 2003); the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation (2002); the Richard Florsheim Art Fund Museum Award, for the purchase of her work by the Museum of Arts & Design (2001); the Hereward Lester Cooke Foundation; and the Ludwig Vogelstein Foundation (1984).[15][9]

In 2006, Temkin's Tribeca studio was used as a set on NBC's Law & Order: Criminal Intent (the Season 5 episode "Slither," aired January 15), with her painting Spiral (2004) featured prominently.[39]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin, Lois. "Extreme Scrutiny," Surface Design, Winter, 2003, p.22-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nahas, Dominique. "Merle Temkin: Close Encounters," Merle Temkin: Portfolio Collection, Brighton, England: Telos Publishing, 2005.

- 1 2 3 Nance, Kevin, "Art exhibit redefines 'handmade': Merle Temkin's 'Fingerprints' at Cultural Center," Chicago Sun-Times, January 17, 2007, p. 41.

- ↑ Fleming, Lee. "Adventures at Artpark," Washington Review, October/November, 1981, p. 6-7.

- 1 2 Brenson, Michael. Review, New York Times, May 16, 1986.

- 1 2 School of the Art Institute of Chicago Magazine, Fall 2017, p. 52.

- 1 2 RISD XYZ, Winter 2017, p. 72. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- 1 2 RISD XYZ, Winter 2017, p. 64. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Temkin, Merle. Merle Temkin: Personal Markings, New York: A.R.T. Press, catalogue, 2000.

- ↑ Heresies, "Feminism and Ecology", Issue #13, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1981.

- ↑ Moore, Sabra. Openings: A Memoir from the Women's Art Movement, New York City 1970-1992, New York: New Village Press, 2016.

- 1 2 Martin, Lois. "Extreme Scrutiny," Merle Temkin: Portfolio Collection, Brighton, England: Telos Publishing, 2005.

- ↑ MoMA exhibition archives. "The Artist in Place: The First Ten Years of MoMA PS1." Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ The MoMA PS1 Archives 1976–2000. Organized by Peter Eleey, Chief Curator. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- 1 2 Merle Temkin website, biography. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Page, Judith. Interview in Merle Temkin: Personal Markings, New York: A.R.T. Press, 2000.

- ↑ Silverthorne, Jeanne. Review, Artforum, November 1981.

- 1 2 Ries, Martin. Catalogue essay, Area Sculpture – Ward's Island, New York: AREA, June 1981–April 1982.

- ↑ Glueck, Grace. Review, New York Times, July 6, 1984.

- ↑ ArtPark. Artpark'81/Lewiston, New York Visual Arts, 1981.

- ↑ Freedman, Susan. Public Art Fund Anniversary Edition 1977–1987, New York: Public Art Fund, 1988, p.19.

- ↑ Ben-Haim, Tsipi. "Arts Festival of Atlanta," International Sculpture, November/December, 1985.

- ↑ Socrates Sculpture Park: Thirty Years. New York: Socrates Sculpture Park, 2016.

- ↑ Temkin, Merle. Artist statement, Grass Roots Art Energy, New York: Socrates Sculpture Park, 1992.

- ↑ Richard, Paul. "The guerillas of art," Washington Post, Style, March 24, 1981.

- ↑ Sozanski, Edward J. "Healthy Abstraction," Philadelphia Inquirer, May 6, 2005, p. W27.

- ↑ Norris, Doug. "Five artists make their points known," South County Independent, February 28, 2002, p. C2.

- ↑ Temkin, Merle. "'Fingerprints' exhibition, artist statement," Chicago Cultural Center, 2007.

- ↑ Dinoto, Andrea. "Corporal Identity—Body Language," American Crafts, April/May 2004.

- ↑ McAdam, Barbara A. "Corporal Identity—Body Language," ARTnews, April 2004.

- ↑ Bischoff, Dan. "psst……somebody's watching you," Sunday Star-Ledger, February 12, 2006.

- ↑ Van Siclen, Bill. "Beneath the surface at URI," Providence Journal, February 21, 2002, p.12.

- ↑ Merle Temkin website, Statement. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ↑ Jenkins, Mark. "Rooted in nature but not always natural," Washington Post, March 6, 2015.

- ↑ RISD Museum. "Portfolio," ed. Sarah Ganz Blythe, Manual: journal about art and its making Issue #10, Spring, 2018, p. 29.

- ↑ Fiberarts, "Commissions," November/December, 2010.

- ↑ Temkin, Merle. Merle Temkin: Portfolio Collection, Brighton, England: Telos Publishing, 2005.

- ↑ Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Merle Temkin page. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ↑ Good, Liz. "Prime Time," Fiberarts, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2006, p.12.