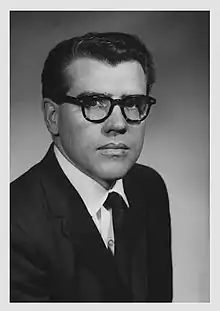

Merrill Bradshaw (June 18, 1929 – July 12, 2000) was an American composer and professor at Brigham Young University (BYU), where he was composer-in-residence from 1967 to 1994.

Bradshaw grew up in Lyman, Wyoming; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Portland, Oregon. He was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). He studied music theory at BYU with John R. Halliday and others, after which he continued his studies in composition at the University of Illinois. He became a faculty member at BYU in 1957. He was chairman of composition and theory from 1973 to 1983, and the executive director of the Barlow Endowment for Music Composition from 1983 to 1999. From 1973 to 1978 he chaired an LDS Church committee to revise the hymnbook, although the committee was suspended before they published their intended hymnal. A different committee authored the 1985 hymnal.

Bradshaw composed many pieces in an eclectic style, most notably The Articles of Faith (1960), Symphony No. 3 (1967), Symphony No. 4 (1969), "Psalm XCVI" (1979), Four Mountain Sketches (1974), the oratorio The Restoration (1974), and a viola concerto titled Homages (1979). He collaborated closely with BYU ensemble directors Ralph Laycock and Ralph Woodward, who often directed premieres of his works. He condemned music that was sentimental or merely entertaining but acknowledged that Mormon art could encompass many styles.

Early life and education

Bradshaw was born on June 18, 1929, in Lyman, Wyoming, to Melvin K. Bradshaw and Lorene Hamblin. He went to junior high school in Salt Lake City and high school in Portland, Oregon, while his father oversaw the construction of air landing facilities in the Aleutian Islands. The family moved back to Lyman, where Bradshaw graduated from high school as valedictorian.[1] While in Lyman, Bradshaw traveled 120 miles (190 km) on Saturdays to study piano with Frank Asper.[2]

Bradshaw started undergraduate studies at Brigham Young University (BYU) in 1947, where he was mentored by John R. Halliday.[3] He served a mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Switzerland from 1948–1951.[4] After returning from his mission, he was accepted into BYU's A Capella choir, where he met Janet Spilsbury, whom he married in 1953.[5] Besides Halliday, Bradshaw studied with Leon Dallin and Crawford Gates at BYU.[6] He was an assistant director of the Reserve Officers' Training Corps Male Chorus for one year and graduated in music theory in 1954.[7] He continued studying at BYU and received a Master of Arts in music theory and composition.[8]

Bradshaw received both a masters in music and a doctorate of musical arts from the University of Illinois, which he attended from 1955 to 1956 and again from 1961 to 1962. There he studied with pianist Claire Richards.[6][9] He also studied with Gordon Binkerd, Robert Kelly, Robert Moffat Palmer, and Burrill Phillips.[10] His doctoral dissertation was "Tonal structure in the early works of Anton Webern."[11] He joined the faculty at BYU in 1957.[12]

Career

Bradshaw was BYU's first composer-in-residence from 1967 to 1994. He was chairman of composition and theory from 1973 to 1983.[13] He worked closely with Ralph Laycock, BYU's orchestra conductor, and Ralph Woodward, the conductor of BYU's A Capella choir, in getting his various compositions performed.[14] Bradshaw was president of the Arts Council of Central Utah and one of its founders in 1968. He also contributed to the State Institute of the Arts.[15][16] He received the Karl G. Maeser Research and Creativity Award in 1967,[17] and was a Distinguished Faculty Lecturer in 1981.[16]

Bradshaw was the executive director of the Barlow Endowment for Music Composition from 1983 to 1999[18] and directed the Barlow International competitions.[6] The Barlow Endowment became a large commissioning program for both LDS and non-LDS composers.[19]

From 1973 to 1978 Bradshaw served the LDS Church as head of composition for the Church Music Committee and also chaired an LDS Church committee to revise the hymnbook.[20] The committee planned to make some hymns lower to encourage everyone to sing the melody line and to include more international songs. They also planned to exclude many hymns present in the 1950 version of the hymnal, including patriotic hymns and most of the men's and women's arrangements. Some people in church leadership disagreed with the committee's decisions, and the committee stopped meeting in 1977. The committee's efforts were suspended without final result in 1978, and the project was not revisited until 1983. The advisory committee to the Church Music Division, a separate committee, decided on the final 1985 version of the hymnal, which was much more similar to the 1950 version than Bradshaw's committee had planned.[21]

Compositions

Bradshaw composed in an eclectic style.[22] Ronald Staheli, later longtime director of acclaimed The BYU Singers,[23] wrote that "Dr. Bradshaw's gift was using musical material or styles that had already been employed by others, but fashioning such harmonies, colors, and styles into works that were true and authentic to his own creative instincts and abilities."[22] He composed music in the style of anthems, lyrical music, and music with noise effects and chord clusters, among other styles. He set Mormon texts to styles that were not intended for worship services, as in The Articles of Faith. One critic wrote that Bradshaw softened dissonances and made "tonal allusions."[24] Bradshaw described most of his melodies as "long, somewhat singable," and frequently used chromaticism to "push the bounds of tonality."[25] He often used parallel motion, asymmetric meters, and syncopated rhythms.[26] Bradshaw's work was performed in many orchestras, including the Detroit Symphony, Utah Symphony, Phoenix Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Perth Symphony, and Queensland Philharmonic.[27]

Bradshaw won the composer's award while attending the University of Illinois, and Michael Kurkjian performed his piano concerto in 1958.[28] The Articles of Faith (1960) for solo voices used the text from the LDS Articles of Faith and drew on multiple styles of composition. He avoided popular music idioms. According to Bradshaw himself, he used leitmotifs to "establish a bond between [the layman’s] experience and my expression."[29] Daniel McDavitt, writing on Bradshaw for his dissertation, wrote that the work was "rich in symbolism but lacking in overall coherence."[30]

In 1968 the Utah Symphony played Bradshaw's Third Symphony, which the BYU Symphony had premiered in 1967.[31] A local critic wrote that "his usage of the myriad of contemporary compositional devices show him to be a master craftsman."[32] Glenn R. Williams, a professor of music, wrote that the symphony is "a very lyrical outpouring within the framework of the serial or 12-tone composition" and that the scoring "effectively produce[d] an amazing clarity and balance of the orchestral sonorities."[33]

Bradshaw wrote "Feathers" for the 1968 BYU Summer Music Clinic in honor of Bernard Goodman.[34] In 1969, the BYU Symphony premiered his one-movement Fourth Symphony, which he dedicated to Robert F. Kennedy.[35] "Psalm XCVI" (1979), Bradshaw's best-known chorale work other than his later oratorio, is very technically demanding. Staheli stated in 2011 that the works were the most difficult he had ever conducted. The piece employs a chromatic style, with some polyphony, at times dividing into 12 parts, with many differing rhythmic figures.[36]

The BYU Philharmonic played his Four Mountain Sketches in 1974.[37] Critic Donald Dierks noted that the style of the pieces is old-fashioned; he wrote: "the idiom would have been passé in the 1940s."[38] That same year Bradshaw's oratorio The Restoration premiered at the Mormon Festival of Arts. The oratorio was the product of two years of work and incorporated elements of jazz and popular hymns.[39] The performances sold out within two hours and were well received. Additional performances were given in 1976 and 1980.[40] The oratorio was endorsed by apostle Boyd K. Packer.[41] Fellow Mormon leaders and artists congratulated Bradshaw on his oratorio. Assistant to the university president Lorin Wheelwright wrote that the work would "give our Church members a new sense of confidence in our cultural roots and modes of artistic expression."[42] Samuel Adler asked how Bradshaw could write such a work in "this century," to which Bradshaw replied that he wanted to "speak to the people here [in Provo, Utah]."[43] In the Deseret News, Harold Lundstrom wrote that the work was emotionally expressive but "hardly [...] a traditional oratorio." Noting the many styles of music present in the oratorio, he wrote that there was "something for everyone."[44] McDavitt wrote that it was "accessible, but not condescending."[45]

The International Viola Congress commissioned him to write a viola concerto, Homages, in 1979 in honor of William Primrose.[46] Jun Takahira premiered the work in 1980, with David Dalton directing the U.S. Air Force Orchestra.[47]

Bradshaw wrote "We Will Sing of Zion", which is in the 1985 LDS church hymnal.[48] He also wrote two hymns that are in the Children's Songbook: "The Still Small Voice" and "Listen, Listen".[49] These two hymns are the only two that lack chord symbols, which have accompaniments in unusual modes.[49]

Views on music

In a 1959 column in The Daily Herald, Bradshaw explained that "sentiment and art are miles apart."[50] His distaste for sentiment was apparent in his scathing review of a performance of Mantovani: "Anyone who went to the concert looking for artistic excellence must have come away disappointed unless they were fooled by the 'ballyhoo' and showmanship that preceded the 'concert'."[51] In "Toward a Mormon Aesthetic" he drew comparisons between Plato's ideal and Mormonism's belief in a perfect celestial realm. He wrote that art concentrates on the values of human experience while entertainment seeks to please an audience.[52] In 1995, Bradshaw spoke on the problem of defining a "Mormon style": "Perhaps we have discovered too many successful and inspiring works in too many different styles to be able to commit ourselves irrevocably to a single one. Moreover, I think it neither possible nor desirable to try to set up the parameters for such a style by some sort of manifesto."[53] He encouraged composers to use the style that best expressed their artistic desires.[54]

Personal life

Merrill and Janet Bradshaw had seven children.[6] Bradshaw died on July 12, 2000, in Bountiful, Utah.[16]

Selected works

Many of Bradshaw's works are unpublished or are out-of-print, as Bradshaw did not seek publishers for his work.[55]

Orchestral

- Symphony No. 1 (1957)

- Orchestra Music, Symphony No. 2 (1962)

- Piece for strings (1967)

- Symphony No. 3 (1967)

- Symphony No. 4 (1968)

- Peace Memorial (1971)

- Four Mountain Sketches (1974)

- Centennial Fantasy (1975)

- Yankee Celebration (1975)

- Piece for 2 horns and strings (1977)

- Symphony No. 5 (1978)

- A Symphonic Tribute (1984)

- Descants (1986)

- Kinesis (1988)

- Museum Piece (1993)

- Life Song (1996)

Concertante

- Concerto for piano and orchestra (1955)

- Divertimento for 4 pianos and orchestra (1963)

- Concerto for viola and orchestra (1979)

- Homages, Concerto for viola and small orchestra (1979)

- Concerto for violin and orchestra (1981)

Chamber music

- Meditation for flute and organ (1955)

- Septet for flute, oboe, clarinet and string quartet (1955)

- Dialogue for flute and horn (1956)

- Suite for viola alone (1956)

- Sonata for violin and piano (1956)

- String Quartet No. 1 (1957)

- 3 Sketches for viola (1963?)

- Sonatina for flute and piano (1965)

- Suite for oboe and piano (1965)

- Brass Quintet (1969)

- String Quartet No. 2 (1969)

- Duo for flute and clarinet (1980)

- Tales from the Desert Winds for string quartet (1982)

- Fantasy for clarinet and piano (1983)

- Foretaste for string quartet (1984)

- Fantasy Dialogues for cello and piano (1989)

Piano

- Beneath the Sea (1953)

- Sarah's Soliloquy (1967)

- Der Schwyzer Missionar (1988?)

- Visionscape (1991)

Choral

- The Articles of Faith for chorus a cappella (1960)

- Music for Oedipus (1968)

- Three Psalms for chorus a cappella (1971)

- Christ Metaphors, Festival of Images for chorus and orchestra (1989)

- The Restoration, Oratorio for chorus and orchestra (1973)

Vocal

- 3 Songs on Verses by Samuel Hoffenstein (1962)

- Come Ye Disconsolate for soprano and piano (1984)

References

- ↑ Maxwell; McDavitt 2011, p. 4

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1974c.

- ↑ Bradshaw Archive photos 1.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Maxwell.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1954.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ "Claire Richards, Pianist". archives.library.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ↑ Pfitzinger 2017.

- ↑ Bradshaw 1962.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1967.

- ↑ Pfitzinger 2017; McDavitt 2011, p. 7; Maxwell

- ↑ Maxwell; Deseret News 2000

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1968.

- 1 2 3 Deseret News 2000.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1967b.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 7.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Hicks 2011.

- 1 2 McDavitt 2011, p. 43.

- ↑ Gallagher, Alisha (November 22, 2015). "BYU's one-bus choir: Dr. Ronald Staheli bows out after founding and leading the BYU Singers". UtahValley360. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 57.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ Bradshaw Archive photos 2; Alton Evening Telegraph 1958

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 67.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 77.

- ↑ The Daily Utah Chronicle 1968; The Daily Herald 1967c

- ↑ Sardoni 1968.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1967c.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1968b.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1969.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, pp. 81, 85.

- ↑ The Daily Herald 1974a.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ Givens 2007.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 88.

- ↑ Givens 2007; The Daily Herald 1974b

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 89.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 90.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 93.

- ↑ Bradshaw Archive - Homages; Bradshaw Archive - works

- ↑ Journal of the Violin Society of America 1980.

- ↑ Hymn #47 1985.

- 1 2 Graham 2007.

- ↑ Bradshaw 1959.

- ↑ Bradshaw 1959b.

- ↑ Bradshaw 1981.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 40.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 41.

- ↑ McDavitt 2011, p. 1.

Works cited

From the Merrill Bradshaw archive

- "Merrill Bradshaw pictures: Mission". Harold B. Lee Library. August 17, 2001. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- "Merrill Bradshaw Pictures: Piano Concerto". Harold B. Lee Library. August 17, 2001. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- "Homages a Concerto for Viola and Small Orchestra". The Merrill Bradshaw Archive. Harold B. Lee Library. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016.

- "Works listed by genre". Harold B. Lee Library. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015.

Books and journal articles

- Bradshaw, Merrill (1962). "Tonal structure in the early works of Anton Webern". search.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Bradshaw, Merrill (Winter 1981). "Toward a Mormon Aesthetic". BYU Studies. 21 (1). Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- Givens, Terryl C. (2007). People of paradox: a history of Mormon culture. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195167115.

- Graham, Patricia Kelsey (2007). We Shall Make Music: Stories of the Primary Songs and how They Came to be. Cedar Fort, Inc. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-0882908182.

- Hicks, Michael (2011). Whittaker, David J.; Garr, Arnold K. (eds.). A firm foundation: church organization and administration. Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University. ISBN 978-0-8425-2785-9. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Hymns. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1985. p. Hymn #47.

- "Journal of the Violin Society of America". 5. 1980: 88.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Maxwell, Karen Bradshaw. "Biography". The Merrill Bradshaw Archive. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016.

- McDavitt, Daniel (2011). "A survey of the choral music and writings of Merrill Bradshaw and analyses of representative works" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pfitzinger, Scott (2017). Composer genealogies: a compendium of composers, their teachers, and their students. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 68. ISBN 9781442272248.

- Sardoni, Lawrence (April 19, 1968). "Bradshaw Work Termed Outstanding: Contemporary Music Featured in Provo Concert by Utah Symphony". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. p. 5.

News articles

- "10 Professors Receive Maeser Funding Awards". The Daily Herald. May 10, 1967. p. 3.

- "Art Council Organized for County". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. December 3, 1968. p. 2.

- "Audience Likes 'New Music'... Reviewer Doesn't: Here's At Least One Person Who Found Mantovani A Little Less Than Perfect". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. April 2, 1959.

- Bradshaw, Merrill (August 9, 1959). "About Sentimentality in Art: Theme and Variations". The Daily Herald. p. 20.

- "BYU Philharmonic to Present Concert". The Daily Herald. Provo, Utah. March 3, 1974a. p. 42.

- "BYU to Present Festival of Arts". The Daily Herald. March 3, 1974b. p. 42.

- "BYU's Orchestra Will Premier Musical Tribute to R. Kennedy". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. May 18, 1969. p. 25.

- "Concerts Will Climax Summer Music Clinic". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. August 8, 1968.

- "Monti Musician on Concert Tour". Alton Evening Telegraph. April 9, 1958. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- "New Bradshaw Composition: Major Work Unveiled At BYU Symphony Concert". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. March 17, 1967. p. 2.

- "Oratorio to Premiere at Festival of Arts". The Daily Herald. Provo, Utah. February 17, 1974c. p. 27.

- "Premiere Tuesday Night: Composer Tells about New Symphony". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. March 15, 1967. p. 7.

- "Senior Piano Recital Today". The Daily Herald. Provo, UT. March 7, 1954. p. 21.

- "Services Tuesday for Merrill Bradshaw". DeseretNews.com. July 17, 2000.

- "Three Works Premiere Tonight". The Daily Utah Chronicle. Salt Lake City, Utah. April 19, 1968. p. 5.