Mexican lacquerware (laca or maque in Mexican Spanish) is one of the country's oldest crafts, having independent origins from Asian lacquerware. In the pre-Hispanic period, a greasy substance from the aje larvae and/or oil from the chia seed were mixed with powdered minerals to create protective coatings and decorative designs. During this period, the process was almost always applied to dried gourds, especially to make the cups that Mesoamerican nobility drank chocolate from. After the Conquest, the Spanish had indigenous craftsmen apply the technique to European style furniture and other items, changing the decorative motifs and color schemes, but the process and materials remained mostly the same. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the craft waned during armed conflicts and returned, both times with changes to the decorative styles and especially in the 20th century, to production techniques. Today, workshops creating these works are limited to Olinalá, Temalacatzingo and Acapetlahuaya in the state of Guerrero, Uruapan and Pátzcuaro in Michoacán and Chiapa de Corzo in Chiapas.[1]

Guerrero

Olinalá

The Mexican state of Guerrero is located to the southwest of Mexico City and is home to three towns that make lacquered products, Olinalá, Temalacatzingo and Acapetlahuaya.[2] The state has a large indigenous population and a strong handcraft tradition.[3] Lacquerware from the state includes utensils, gourds, chests and other furniture, storage boxes, toy cars and helicopters, trays and even musical instruments.[2] Guerrero lacquerware from Olinalá and to some extent Temalacatzingo became popularized in the 1970s, and its success has allowed many migrant workers to return home to the town, but there are still high rates of migration out, especially young people, to Mexico City and the United States.[2][3][4]

The town of Olinalá is located in the mountains of the Sierra Madre del Sur, and its wares are the most widely known.[2][5] While pieces are 10 to 50% cheaper in Olinalá, the town is hard to get to.[6] Instead wares are sold in many areas of Mexico and are featured at an important craft fair in Tepalcingo, Morelos, held the third week of Lent,[2] the San Juan Market in Mexico City, and have been exhibited in New York and Japan.[4] Although documented in the 1920s by Rene d’Harmoncourt, the craft almost disappeared from Olinalá by the 1960s, with only twenty master craftsmen left.[4][5] In the 1970s, writer Carlos Espejel popularized it through his work. Today almost all the families in the town are involved in production,[5] and it is the main producer of lacquerware in Mexico.[6] The craft is the main source of income for the town, producing chests, trays, platters, boxes, paneled screens[6] and furniture (usually done on commission).[4] Even the parish church's columns are lacquered, in a style called rayado.[4]

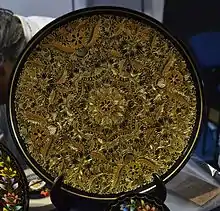

Olinalá lacquerware is divided into two types, depending on the decoration technique used, called rayado (scratched) and aplicado (apliqué). The latter is also sometimes called dorado (gilded) because of the past use of gold paint or gold leaf, which has made something of a comeback.[2][4] Rayado is the more complicated of the two.[6] The name comes from the use of an agave thorn or quill to etch designs.[2][6] One coat is applied to the piece then dried completely. A second coat is applied and while still wet, this layer is removed in places to reveal the first color and create abstract designs and figures such as animal and humans.[2][4] Most pieces are two-toned: black and red or blue and white.[4] In large pieces, such as chests, abstract designs are combined with figurative, usually flowers and are highly symmetrical.[2] Highly skilled artisans can create two-tone pieces that look like lace or repeat the process to have three or even more colors.[4]

Applicado is where the designs are painted onto a base coat, a technique also done in other parts of Mexico.[2][4] This work traces back to at least the 18th century, and while may include motifs such as patriotic symbols, most are not Mexican, but instead stylized flowers, European landscapes and images from Asia.[2][4] The two techniques can be combined, which is called punteado (dotted), were small dots are painted in areas that are not etched. This became popular starting at the end of the 1970s.[2] Like rayado pieces, animals, flowers and geometrical designs are prevalent and all available space is filled.[2][4]

Most Olinalá artisans are anonymous and poor. Pieces are rarely signed and if they are, it is by the person who creates the decorative design.[2][4][6] However, the work is done in family workshops with different members doing different jobs.[2] While women do most of the work,[2] almost all of the rayado work is done by men.[4] Most Olinalá artisans begin as children, learning to blend colors and adding dot patterns, then moving up to creating figures and more complicated designs.[4] Olinalá families often specialize in colors and designs,[4] with techniques and motifs handed down from generation to generation.[6] However, artisans have adapted their works to new markets and new tastes as most of their wares are now sold in Mexico City and abroad.[4] One example is the recent use of pastel colors.[4][6] Other innovations include the use of more modern materials, but the most notable artisan is Margarito Ayala, who still relies completely on traditional methods and materials, including the grinding of chia seeds himself.[4][6]

Temalacatzingo and Acapetlahuaya

The village of Temalacatzingo is located in the municipality of Olinalá.[2] It has a population of about 3,000, most of whom are dedicated to lacquerware along with agriculture.[3] Like Olinalá, lacquer is an industry and sold widely in Mexico, but the production is not as sophisticated in design.[2] These wares often have a bright red background due to the use of a commercial oil paint, and include toys, gourds and gourd pieces used to create carrying apparatus and jewelry.[2][3]

Acapetlahuaya is located just off the road between Iguala and Ciudad Altamirano, near Teloloapan. Acapetlahuaya's production is only for local use, and is limited to gourds. These are in the same style as those of Olinalá and do not use commercial pigments.[2]

Michoacán

In the state of Michoacán, west of Mexico City, the making of lacquerware can be found in Uruapan, Pátzcauro and Quiroga.[7] One distinctive element of Michoacán traditional lacquerware is the use of “aje,” the larvae of the (coccus axin) insect, from which a waxy substance is extracted. This is mixed with chia or linseed to create the lacquer.[8]

The center of lacquerware in this state is the city of Uruapan, founded by missionary Juan de San Miguel. Like contemporary Vasco de Quiroga in nearby Pátzcuaro, he worked to protect the local indigenous and organized handcraft production, the origin of this specialization.[9] Today, the city still makes the most intricate of designs, and still uses gold leaf in some of its production, which varies widely from trays, to plates to utensils and decorative items.[10] Victoriano Salgado of Uruapan makes wooden masks that are covered and decorated in lacquer, but this is disappearing because of the waning of traditional masked dance. Most of these masks are now sold to collectors.[11]

Patzcuaro is noted for is deep trays and small boxes,[12] but its designs have not changed much since the 18th century, when the craft was at its peak here and several artisans noted in contemporary records. One of these families, De la Cerda, continues to make lacquerware in the city.[13][14] These traditional patterns include elements of Oriental origin, along with indigenous and European designs.[15]

The town of Quiroga (formerly Cocupa) is located in the same lake area as Pátzcuaro. While considered to be a center of lacquerware, it does not use the traditional techniques and is closer to painted, using natural pigments mixed with vegetable oil.[16] Most of this production is center in the indigenous neighborhood called Arriba and consists of trays and chests made to order.[14] However, small items such as rings, earrings, bracelets and toys can also be found.[17] Despite the different techniques and use of commercial materials, pieces Quiroga can be found in the Museo Regional de Pátzcuaro and the Museo de Huatapera in Uruapan.[16][17]

Chiapas

The center of lacquerware in southern state of Chiapas is Chiapa de Corzo.[18] Traditionally the aje larvae is also used to make lacquer and is used to cover gourds, rattles, crosses, chests and furniture.[19][20]

The decoration of this lacquerware is generally floral and bird designs painted over a back background. There is also Asian influence in Chiapas designs, which can be traced to fans, screens and other times imported through the Manila trade. More recent work as imitated other kinds of designs found on colonial-era pieces.[19][20]

Noted artisans in Chiapas include Rosalba Cameras, Martha Vargas, Blanca Rosales Aguilar, Vicente Clory Díaz, María Angela Nandayapa, Guadalupe Pérez, María Elena Pérez Sánchez, Martha Pérez Sánchez, Sara Pérez, Amparo Díaz, Javier Orozco Palavicini, Blanca Magdalena López Hernández and Verónica Pérez Pérez.[19]

Process

The technical aspects of traditional Mexican lacquerware date back to the pre-Hispanic period. A protective layer of animal and/or plant oil/grease is mixed with powdered minerals and coloring agents to cover an object.[2] One indigenous material used throughout Mesoamerica was the extraction of a greasy substance from the larvae of the coccus axin or llaveia axin insect.[2][21] To extract this substance for lacquering, the larvae are collected and then boiled alive until a yellowish color appears.[22][23] These larvae are then placed in a cloth and then pressed over a container of cold water so that the grease floats to the top to be collected.[12][22][24] The substance is left to cool and congeal for one or two days until it has the consistency of butter.[22][24][25] The use of this substance is mostly confined to Michoacán and Chiapas, with the area of Huetamo, Michoacán noted for its production.[23] Before it is used to lacquer, it is traditionally cut with chia (savia chian) or chicalote (argemona Mexicana) oil, but today European linseed oil is also used.[24] This thins the material and quickens drying time.[12] In Guerrero, only chia or linseed oil is used.[2]

The most traditional lacquered objects in Mexico are made from gourds that grow on vines (genus Lagenaria) or on trees (genus Crescentia) and are called by various indigenous names. Bottle-like gourds are generally cut so that the narrower top end serves as a lid. These containers are called sewing boxes or powder containers, but they are generally used to store knickknacks. Rounder gourds are cut to make cups or bowls.[2]

Since the colonial period, a wide variety of wood items has been treated in the same way. The most traditional wood for lacquerware is linaloë (genus Burseraceae). It is popular for its strong, pleasant odor, similar to lavender, but it has become scarce.[18][23] Good pieces are still made from hard or semi-hard wood,[23] but most are now made from avocado or pine wood which has been boiled to remove the resin.[2] Linaloë essence may be added for the smell.[4][6] In the past, lacquer makers also created the wood objects, but with the introduction of power woodworking tools, this aspect has been outsourced to local carpenters who can make them cheaper.[5][26] However, the wood pieces must be completely dry, sanded fine and cracked filled before any lacquering begins.[23][27]

Traditional lacquer is made with aje and/or oils mentioned above, mixed with a mineral called dolomite, creating a white or sometimes light yellow base.[24][27] This base is then colored with natural pigments,[28] such as indigo for blue and charcoal for black.[29] However, in Guerrero other minerals may be used to create colors without other pigments such as tecostle for ochre, and toctel for a very pale green.[2] The mixture as a creamy texture and is either applied with a deer tail or with the hands, rubbing it in.[7][30] The base color may be applied several times, and left to dry for fifteen to twenty days between applications.[4]

All layers of lacquer, whether it covers the piece completely or not must be applied separately, dried and then burnished to fix.[31] Two colors cannot be applied at the same time close to each other because of the risk of smudging.[27][32] For decorative elements, sometimes an inlay technique is used, hollowing a slight depression to be filled by the colored lacquer.[12] The burnishing for both affixing and polishing makes the process labor-intensive. The shining is usually done with the palm of the hand for a finer result.[6][31] The entire process of applying the lacquer on a small piece can take at least twenty days and after final polishing the piece by dry for months.[27][33] If gold leaf is to be applied, it must be done after all lacquering and the piece is completely dry.[33]

Technique, colors and motifs vary somewhat from region to region[12] as well as quality, which may even be noticeable to the untrained eye.[6] Since the early 20th century there has been a change in the materials used, substituting plaster for dolomite, linseed oil and even car wax for chia or aje and commercial pigments for natural ones. One reason for this is the natural materials are becoming scarce and more expensive.[34] Many artisans now buy the wood pieces pre-sanded and with the black background already painted on, dedicating themselves only to the decoration.[26]

History

Lacquering is one of Mexico's oldest crafts.[5] In Mexican Spanish, it is usually called either laca or maque (from Japanese maki-e),[2][12] somewhat interchangeably but the term maque is most often used in Michoacán and can be used to distinguished work that uses the wax from the aje insect larvae.[35] In Olinalá, lacquered pieces are referred to as obras (works of art) .[2] The history of the craft can be divided into four periods – the pre-Hispanic period, the colonial period (to the Mexican War of Independence), the 19th century, and the 20th century to the present.[36]

Pre Hispanic period

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, lacquering was known in all of Mesoamerica from central Mexico into Guatemala,[2] with the use of aje grease documented in areas such as modern Oaxaca, Veracruz, Yucatán, Chiapas, Guerrero and Michoacán.[37] However, most of what is known of the period is from early colonial texts of chronicler such as Bernardino de Sahagún and Francisco Ximénez describing the lacquered objects they came in contact with.[2][4][20] However, the Spanish did not identify the work as lacquer until the 18th century, with records only stated that the items were painted.[38] Until the 1950s there was debate as to whether Mexican lacquerware was of Oriental origin. This was settled with the discovery to lacquerware fragments from before the Conquest in places such as the Cueva de la Garrafa in Chiapas.[20]

While objects of wood, ceramic and onyx received the treatment, by far it was used on dried gourds most commonly.[2] The gourds have a long history of being used for the creation of cups and other dishes, especially those for the drinking of chocolate by Mesoamerican nobles.[4][12] They were also used to make storage containers and decorative items.[2][39] Today these lacquered jícaras (from Nahuatl xicalli) are still popular, either whole as a decorative object or split to create a bowl for eating or drinking.[2]

Colonial period

After the Conquest, indigenous carpenters began making European style furniture and indigenous lacquer makers began decorating them with European motifs.[12][40] The lacquering process remained the same, with changes only in the enhancement of the color palette, and in the introduction of new coloring agents.[8] This lacquer was cheaper than importing items from Europe or Asia and items[12] includes large chests (called baúl or arcón), trays, wood storage boxes, along with church furniture and other items.[2][41]

The decoration of all lacquered items during the colonial period was mostly European, especially floral designs (which may include some native flora) along with European landscapes. These could be framed by geometric fretwork.[42] Another strong influence on Michoacán lacquerware was the Church, with the appearance of religious symbols.[43] One other influence was the Asian goods that flowed into Mexico due to the Manila trade, both Asian lacquer and other decorative objects.[44] Many of these objects traveled through Michoacán from the port of Acapulco on their way to Mexico City, passing through the lacquer center of Uruapan and Pátzcuaro, because of the road system and internal customs checkpoints. Copies of Oriental lacquerware, such as folding screens began to appear in Pátzcuaro, and it influenced the designs on work done in Uruapan.[13][43] Eventually these motifs and styles mixed with the European and native to continue in traditional lacquer patterns in Michoacán and elsewhere in Mexico.[15] The work done in Uruapan in the height of the colonial period has been divided into four styles of “families,” based on motifs. Florones are distinguished with a large floral pattern in the center surrounded by fretwork. Guirnaldas also have the large floral center but is surrounded by fretwork and foliage. Escudos have coats-of-arms painted among fretwork, related to the family that ordered the piece. Ramilletes also have coats-of-arms but is the most Baroque in style, with more opulent colors.[45]

Lacquerwork was most organized in the state of Michoacán, where missionaries such as Vasco de Quiroga organized and promoted trades by having towns specialize. Uruapan, Pátzcuaro and the town now known as Quiroga was dedicated to lacquer, each with its own unique characteristics.[38][46] There was also a fourth, Peribán, but it has since disappeared, leaving behind only the name of a style of large, deep lacquered tray called a peribana in the state.[35] During the colonial period, Uruapan became the most important lacquerware center, producing the best pieces including those with gold leaf and other precious and semi-precious inlays. It also produced a wider variety of designs, often based on the exuberant vegetation of the region.[40]

Lacquerware went through fashions. For example, in the mid 17th century, wood oval trays with scenes from Don Quixote were very popular.[47] However, by the end of the colonial period, the upper-class clientele for lacquered furniture were able to buy this and many decorative items from Europe, limiting Mexican lacquer work to small boxes and other trinkets.[12]

19th century

In 1810, the Mexican War of Independence broke out and for the next eleven years, the lacquer industry waned, along with most other handcraft production, until it nearly disappeared. The main reasons for this were the lack of money for such goods, the dangerous roads making it difficult to get goods to market and the temporary closure of regional fairs which were important outlets.[48][49]

Lacquerwork rebounded after 1822, with some being sent to the United States as early as the early 19th century. Styles changed and to some extent, technique.[48][49][50] The decoration of lacquerware in this century can be divided into three periods. The early part of the century saw a proliferation of eagle and flag designs representing the newly independent nation. Noble coats-of-arms disappeared but traditional patterns based on flora and fauna continued. This is followed by a period were miniature intricate floral designs dominate and then a period of decline, with highly stylized and poorly executed decoration. The influence of Romanticism led to the use of paler tones with a wider variety of colors including white, yellow and pink backgrounds.[51][52]

20th century

In the very early 20th century, lacquerware in Michoacán made something of a comeback with innovations in design and production. One reason for this was that this work was chosen as part of the state's delegation to the 1904 Saint Louis World's Fair.[52][53] The work done in Uruapan was chosen, but the pieces that were created for the exhibition were not of traditional designs, which were considered primitive, especially native Purépecha elements and color combinations. Instead colonial floral designs were updated and the geometric fretwork was replaced by that based on Art Nouveau. The success of these pieces at the event as well as foreign demand for the lacquerware mean that pieces produced from then on have had less variation in style and fewer opportunities for artisans to create variations.[54]

The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution again suppressed the production of lacquerware in Mexico, and made it endangered.[50] One permanent effect was the disappearance of pieces with gold leaf in places like Pátzcuaro.[55] The main market for Uruapan lacquerware was the United States,[48] but the market for lacquerware from Guerrero has almost disappeared until the 1970s, when writer Carlos Espejel began to promote it, especially the work of Olinalá.[2] The Mexican government established the National Fund for the Development of Arts and Crafts (FONART) during this decade as well, and Olinalá wares were chosen for promotion, in part because they are lightweight and easy to transport.[2][4] The craft began to be promoted to the country's tourism industry, which had been growing since the 1950s.[56] Since then lacquerware has made a comeback in these two states but the quality and quantity of production varies considerably.[4]

In the 1920s, the popular art of Mexico began to be investigated scientifically, including lacquerware, documenting its production and processes. New and antique pieces were collected and placed into museums such as the Museo Regional de Arte Popular de Pátzcuaro and the Museo de la Huatapera. These collections are of use both to academics and new generations of artisans for study.[57] There are also schools for the training of new lacquer artisans such as that of the Museo de las Artes e Industrias Populares de México and the Salvador Solchaga Workshop of the Casa de los Once Patios in Patzcuaro.[57]

However, the rise in production has forced changes in both materials and productions techniques. In the 1980s the wood of the linaloe was exported to extract its essence making it scarce and most pieces are now made with other woods, including pine.[18] While artisans using traditional methods and materials still exist, plaster has been substituted for dolomite, linseed oil and even car wax for chia or aje and commercial pigments for natural ones. One reason for this is the natural materials are becoming scarce and more expensive.[34][58]

The present

Today lacquer production is limited a few towns in the states of Michoacán, Chiapas and Guerrero.[4] These centers mostly produce for markets in other parts of Mexico and abroad. In Mexico City, these wares can be found in the San Juan Market, the Ciudadela Market, FONART stores, the specialty shops in San Ángel and the weekend crafts market in the center of Coyoacán.[4] Outside of Mexico, lacquerware is most popular in the United States, Europe and Japan.[6] The craft has brought tourism to places like Uruapan and Olinalá from these parts of the world, even despite Olinalá's remoteness.[4] Noted artisans include Francisco Coronel, who won the National Arts and Sciences Award in 2007 along with Mario Agustín Gaspar and Martina Navarro from Michoacan.[1]

While only fragments from the pre Hispanic period and a few full pieces from the colonial period and 19th century survive,[2][20][59] various collections of lacquer pieces can be found in collections such as those of the Unidad Regional de Culturas Populares in Guerrero[1] and the Museo de la Laca in Chiapa de Corzo.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 "Inauguran en el MNCP muestra artesanal sobre la laca en México". NOTIMEX. October 9, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Ted J.J. Leyenaar. "Mexican lacquers from Guerrero /La laca Mexicana de Guerrero" (PDF). Netherlands: National Museum of Ethnology Museum Volkenkunde. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Plasma indígena de Guerrero sus sueños en artesanía de bule con laca". NOTIMEX. Mexico City. August 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Barbara Belejack (May 27, 1990). "SHOPPER'S WORLD; Colorful Folk Motifs In Mexico's Lacquerware". New York Times. New York. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marion Oettinger, Jr (2010). Folk Treasures of Mexico: The Nelson A. Rockefeller Collection. Mexico City: Arte Publico. p. 55. ISBN 978-1558855953.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Jennifer Merin (January 20, 1991). "In Olinala, Crafting Lacquerware Is Way of Life". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- 1 2 De P. León, p. 25

- 1 2 De P. León, p. 22

- ↑ De P. León, p. 13

- ↑ De P. León, p. 94

- ↑ Jesus Pacheco (December 21, 2003). "De maque, colorin y talento". Mural. Guadalajara. p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kathryn Santner (October 2, 2012). "Writ in Lacquer: A Genteel Courtship on a Mexican Sewing Box". Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- 1 2 Thele, p. 24

- 1 2 Thele, p. 65

- 1 2 Thele, p. 21

- 1 2 Thele, p. 25

- 1 2 Thele, p. 68

- 1 2 3 Harry Möller (August 3, 2008). "México Channel / Algo sin igual sucede en Olinalá". Reforma. Mexico City. p. 10.

- 1 2 3 "Inauguran hoy muestra sobre la laca en Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas". NOTIMEX. Mexico City. July 31, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Laca". Mexico: Casa de Chiapas (Government of Chiapas). Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ↑ De P. León, p. 14

- 1 2 3 De P. León, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thele, p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 Thele, p. 36

- ↑ De P. León, p. 41

- 1 2 Thele, p. 66

- 1 2 3 4 De P. León, p. 24

- ↑ Thele, p. 37

- ↑ De P. León, p. 34

- ↑ De P. León, p. 32

- 1 2 Thele, pp. 39–41

- ↑ Thele, p. 40

- 1 2 Thele, p.44

- 1 2 Thele, pp. 57–58

- 1 2 Thele, p.12

- ↑ De P. León, p. 105

- ↑ De P. León, p. 28

- 1 2 Thele, p. 11

- ↑ De P. León, p. 106

- 1 2 Thele, p. 13

- ↑ De P. León, p. 98

- ↑ De P. León, p. 111

- 1 2 Thele, p. 16

- ↑ De P. León, p. 103

- ↑ Thele, p. 20

- ↑ De P. León, p. 93

- ↑ De P. León, pp. 17–18

- 1 2 3 De P. León, p. 16

- 1 2 Thele, p. 45

- 1 2 De P. León, p. 95

- ↑ De P. León, p. 113

- 1 2 Thele, p. 46

- ↑ De P. León, p. 114

- ↑ Thele, pp. 51–53

- ↑ Thele, p. 58

- ↑ Cathy Winkler (1986). Changing power and authority in gender roles: Women in authority in a Mexican artisan community (Thesis). Indiana University. OCLC 8727476.

- 1 2 Thele, p. 63

- ↑ Thele, p.64

- ↑ De P. León, pp. 98–99

Bibliography

- Francisco de P. León (1922) [1922]. Los esmaltes de Uruapan. Mexico City: Editorial Innovación.

- Eva-María Thele (1982). El maque: Estudio histórico sobre un bello arte. Mexico City: Instituto Michoacano de Cultura/Grama Editora.