Michèle Moet-Agniel | |

|---|---|

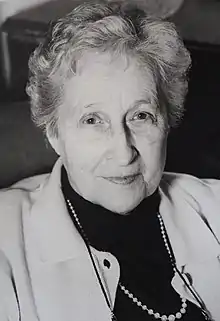

Agniel in 2005 | |

| Birth name | Michèle Moet |

| Born | 11 June 1926 Paris |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | French Resistance |

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Unit | Burgundy Network |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Michèle Moet-Agniel (b. 11 June 1926, Paris) was a member of the French Resistance, distributing leaflets and later helping Allied aviators escape back to Britain. She was arrested and deported to the Ravensbruck concentration camp, but was rescued by Russian soldiers. After the war, Agniel became a teacher.

Early life

Michèle Moet-Agniel was born Michèle Moet in 1926 in Paris to a French World War I veteran and a Dutch immigrant.[1][2]

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II, Moet-Agniel, then 14, was on vacation with her family at Fort-Mahon-Plage. They stayed there until May 1940, returning to Paris on foot. Her family became supporters of Charles de Gaulle's Free French Army. Moet-Agniel's activities in the Resistance began with graffiti art near the Porte de Vincennes of the Free French emblem. In November, Moet-Agniel's former English teacher gave tasked her with retrieving a bundle of leaflets from Versailles and distributing them.[3]

From their home in Saint-Mandé, the Moets hid French, British, and American soldiers and provided them with false documents for the Burgundy Network. Moet-Agniel's father, working at his local town hall,[4][5] forged and recycled the documents of deceased French citizens so that the errant Allied personnel could receive German-rationed food.[2]

In October 1943, aged 17, Moet-Agniel accompanied a member of her network to Britain and would personally assist downed Allied aviators getting to England.[4][2]

Arrest and deportation

On 28 April 1944, German officials arrested the Moets with two Englishmen. They were taken Nogent-sur-Marne, then to Fresnes Prison. The family escaped torture, but were deported to Germany on 15 August, just before the liberation of Paris. Moet-Agniel's father died in Buchenwald in March 1945 while Moet-Agniel and her mother were interned at Ravensbruck. They were freed when the Red Army reached the camp on 5 February 1945, then were repatriated to Paris on 21 June.[6]

Post-war

For her role in the escape of several Allied servicemen, Moet-Agniel received a number of distinctions from France, the United States, and the United Kingdom. When Elizabeth II and Philip visited Paris 1948, Moet-Agniel was presented to them.[6]

After the war, Moet-Agniel resumed her education, became a teacher, and married a Mr. Agniel. In the 1980s, she testified against Holocaust denial as a witness.[6]

Legacy

A street in the French town of Migné-Auxances is named after Moet-Agniel.[7] Bobbie Ann Mason's 2011 novel The Girl in the Blue Beret is based on Moet-Agniel's activities in the Resistance and particularly her aid of Mason's father-in-law.[8]

Moet-Agniel was given an American flag that had flown over the US Capital on behalf of Senator Johnny Isakson.[9]

Citations

- ↑ Rameau 2008, pp. 66–68.

- 1 2 3 Rameau 2015, p. 194.

- ↑ Rameau 2008, p. 68.

- 1 2 Rameau 2008, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Giard & Lebeau 1966, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 Rameau 2008, p. 69.

- ↑ "Résistante, elle voit une rue prendre son nom". La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest (in French). 2 April 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ↑ Mason, Bobbie Ann (18 May 2013). "The Real Girl in the Blue Beret". The New Yorker. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ↑ "Michèle Agniel". Saving the Rabbits of Ravensbrück. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

References

- Giard, Maurice E.; Lebeau, Pierre (1966). Saint-Mandé, notre ville (1075-1965) (in French). La Tourelle.

- Rameau, Marie (2008). Des femmes en résistance: 1939-1945 (in French). Éditions Autrement. ISBN 978-2-7467-1112-9.

- Rameau, Marie (2015). Souvenirs (in French). Éditions La ville brûle. ISBN 978-2-36012-064-2.