| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

The military history of Taiwan spans at least 400 years and is the history of battles and armed actions that took place in Taiwan and its surrounding islands. The island was the base of Chinese pirates who came into conflict with the Ming dynasty during the 16th century. From 1624 to 1662, Taiwan was the base of Dutch and Spanish colonies. The era of European colonization ended when a Ming general named Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) retreated to Taiwan as a result of the Ming-Qing War and ousted the Dutch in 1661. The Dutch held out in northern Taiwan until 1668 when they left due to indigenous resistance. Koxinga's dynasty ruled southwestern Taiwan as the Kingdom of Tungning and attacked the Qing dynasty during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories (1673-1681).

In 1683, the Qing invaded Taiwan and ousted the Zheng regime, establishing Taiwan Prefecture (later Taiwan Province) in southwestern Taiwan. The Qing administration lasted for over two centuries, during which it rarely tried to conquer the Taiwanese indigenous peoples and instead tried to restrict settlers from entering Taiwan. Despite official restrictions, Han Chinese settlers increased and crossed into indigenous territory across the western Taiwanese plain, leading to conflicts with indigenous peoples in central and northeastern Taiwan. Most rebellions during the Qing period occurred due to Han discontent while the indigenous people were left to their own devices.

The Qing ceded Taiwan and Penghu to the Empire of Japan after losing the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. There was brief military resistance from Qing forces in Taiwan before retreating, after which decades of Japanese military suppression followed. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Taiwan served as a base for invasions of China, and later Southeast Asia and the Pacific during World War II. Some Taiwanese served in the Japanese military, although not in combat positions until in the late stages of the war. Some 207,000 Taiwanese served in the Imperial Japanese military and 50,000 Taiwanese Imperial Japanese Servicemen went missing in action or died.

Following World War II and the retreat of the Republic of China to Taiwan in 1949, Taiwan's military has been the Republic of China Armed Forces. Until 1972, a primary aim of the Chiang Kai-shek-controlled armed forces was to retake mainland China by large-scale invasion. In the modern era, the focus of Taiwan's military has been national defense to thwart any possible attacks primarily from the People's Republic of China and its People's Liberation Army forces.

Early conflicts

Early records refer to an eastern island named Yizhou, to which troops of Three Kingdoms state of Eastern Wu visited as early as 230. Some scholars believe this island was Taiwan, while others dispute the theory.[1] The Book of Sui relates that Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty sent three expeditions to a place called "Liuqiu" early in the 7th century.[2] Historically, the name Liuqiu (whose characters are read in Japanese as Ryukyu) referred to the island chain to the northeast of Taiwan, but some scholars believe it may have referred to Taiwan in the Sui period. Okinawa Island may have been referred to by the Chinese as "Great Liuqiu" and Taiwan as "Little Liuqiu".[3]

During the Song dynasty, Han Chinese fishermen settled on the Penghu Islands by 1171, when "Bisheye" bandits, a Taiwanese people related to the Bisaya of the Visayas, landed on Penghu and plundered fields planted by Chinese migrants.[4] The Song dynasty sent soldiers after them, and from that time on Song patrols regularly visited Penghu in the spring and summer. A local official, Wang Dayou, stationed troops there to prevent depredations from the Bisheye.[5][6][7]

During the Yuan dynasty, a patrol and inspection agency (Chinese: 巡檢司) was set up in Penghu around 1281,[8] and Han Chinese people were recorded to have visited Taiwan. Yuan emperor Kublai Khan sent officials to the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1292 to demand its loyalty to the Yuan dynasty, but the officials ended up in Taiwan and mistook it for Ryukyu. After three soldiers were killed, the delegation immediately retreated to Quanzhou in China. Another expedition was sent in 1297.[9]

The Chinese pirates Lin Daoqian and Lin Feng visited Taiwan in 1563 and 1574 respectively. Lin Daoqian was a Hakka pirate from Chaozhou who was chased out of Fujian in 1563 by Ming naval forces led by Yu Dayou and fled to Beigang in southwestern Taiwan. He left the next year to ravage the mainland and stayed active in the region until 1578 when he left for Southeast Asia. Lin Feng moved his pirate forces to Wankan (in modern Chiayi County) in Taiwan on 3 November 1574 and used it as a base to launch raids. They left for Penghu after being attacked by natives and the Ming navy dislodged them from their bases. He later returned to Wankan on 27 December 1575 but left for Southeast Asia after losing a naval encounter with Ming forces on 15 January 1576.[10][11] The pirate Yan Siqi also used Taiwan as a base.[12]

Chen Di visited Taiwan in 1603 on an expedition against the Wokou pirates.[13][14] The pirates were defeated and they met a native chieftain who presented them with gifts.[15] Chen recorded these events in an account of Taiwan known as Dongfanji (An Account of the Eastern Barbarians) and described the natives of Taiwan and their lifestyle.[16]

In 1616, the Tokugawa shogunate sent a fleet of 13 ships and 4,000 warriors in an attempt to conquer Taiwan as part of a larger campaign to strengthen Japanese sea power and facilitate its silk trade. Due to a typhoon, the invasion forces were dispersed, and only one ship reached Taiwan.[17][18]

Dutch and Spanish colonies (1624–1662)

Early contact

In 1542, Portuguese sailors arrived in Taiwan and noted it on their maps as Ilha Formosa (lit. 'beautiful island').[19] In 1582, the survivors of a Portuguese shipwreck spent 45 days battling malaria and aborigines before returning to Macau.[20][21]

Defeated by the Portuguese at the Battle of Macau in 1622, the Dutch East India Company attempted to take Penghu in 1624, building Fengguiwei Fort in Magong. Dutch forces were driven out by Ming authorities and retreated to a sandy peninsula of Tayuan (present-day Anping District) and built a defensive fort to act as a base of operations. This temporary fort was replaced four years later by the more substantial Fort Zeelandia.[22]

Dutch ships wrecked at Liuqiu in 1624 and 1631; their crews were killed by the inhabitants.[23] In 1633, an expedition consisting of 250 Dutch soldiers, 40 Chinese pirates, and 250 Taiwanese natives were sent against Liuqiu Island but met with little success.[24]

Dutch colonization

The Dutch allied with Sinkan, a small village that provided them with firewood, venison and fish.[25] In 1625, they bought land from the Sinkanders and built the town of Sakam for Dutch and Chinese merchants.[26] Initially the other villages maintained peace with the Dutch. In 1625, the Dutch attacked 170 Chinese pirates in Wankan but were driven off. Encouraged by the Dutch failure, Mattau warriors raided Sinkan. The Dutch returned and drove off the pirates. The people of Sinkan then attacked Mattau and Baccluan, and sought protection from Japan. In 1629, Pieter Nuyts visited Sinkan with 60 musketeers. After Nuyts left, the musketeers were killed in an ambush by Mattau and Soulang warriors.[27] On 23 November 1629, an expedition set out and burned most of Baccluan, killing many of its people, who the Dutch believed harbored proponents of the previous massacre. Baccluan, Mattau, and Soulang people continued to harass company employees until late 1633 when Mattau and Soulang went to war with each other.[27]

In 1635, 475 soldiers from Batavia arrived in Taiwan.[28] By this point even Sinkan was on bad terms with the Dutch. Soldiers were sent into the village and arrested those who plotted rebellion. In the winter of 1635 the Dutch defeated Mattau and Baccluan. In 1636, a large expedition was sent against Liuqiu Island. The Dutch and their allies chased about 300 inhabitants into caves, sealed the entrances, and killed them with poisonous fumes. The native population of 1100 was removed from the island.[29] They were enslaved with the men sent to Batavia while the women and children became servants and wives for the Dutch officers. The Dutch planned to depopulate the outlying islands.[30] The villages of Taccariang, Soulang, and Tevorang were also pacified.[27] In 1642, the Dutch massacred the people of Liuqiu island again.[31]

In 1636, Favorolang, the largest aboriginal village north of Mattau, killed three Chinese and wounded several others. From August to November, Favrolangers appeared near Fort Zeelandia and captured a Chinese fishing vessel. The next year the Dutch and their native allies defeated Favorolang. The expedition was paid for by the Chinese populace. When peace negotiations failed, the Dutch blamed a group of Chinese at Favorolang. The Favorolangers continued their attacks until 1638. In 1640 an incident involving the capture of a Favorolang leader and the ensuing death of three Dutch hunters near Favorolang resulted in the banning of Chinese hunters from Favorolang territory. The Dutch blamed the Chinese and orders were given to restrict Chinese residency and travel. No Chinese vessel was allowed around Taiwan unless it carried a license. An expedition was ordered to chase away the Chinese from the land and to subjugate the natives to the north. In November 1642, an expedition set out northward, killing 19 natives and 11 Chinese. A policy banning any Chinese from living north of Mattau was implemented. Later the Chinese were allowed to conduct trade in Favorolang with a permit. The Favorolangers were told to capture any Chinese who did not possess a permit.[32]

Spanish colony

In 1626, Spanish forces landed at Cape Santiago in northern Taiwan. They eventually moved westward to modern-day Keelung, where they established Santisima Trinidad as a base for the new colony.[33] They seized the territory from aboriginal inhabitants or destroyed their residences, promising to pay for the damages. According to historian Jose Eugenio Borao Mateo, the Spanish colonists did not ask for tribute from the aboriginal inhabitants, "because in practice they did not consider the natives as vassals, but as heathens to be converted, neighbors and service suppliers."[34]

In 1641, governor of Dutch Formosa Paulus Traudenius launched an expedition on the Spanish settlement of San Salvador in modern-day Keelung. The Spanish positions were well-defended, and Dutch forces were not able to breach the walls of Fort San Salvador. In the following year, the Dutch launched a second assault and successfully captured San Salvador.

Guo Huaiyi rebellion

On 8 September 1652, a Chinese farmer, Guo Huaiyi, and an army of peasants attacked Sakam. Most of the Dutch were able to find refuge but others were captured and executed. Over the next two days, natives and Dutch killed around 500 Chinese. On 11 September, four or five thousand Chinese rebels clashed with the company soldiers and their native allies. The rebels fled; some 4,000 Chinese were killed.[35] The rebellion and its ensuing massacre destroyed the rural labor force. Although the crops survived almost unscathed, there was a below average harvest for 1653. However thousands of Chinese migrated to Taiwan due to war on the mainland and a modest recovery of agriculture occurred. Anti-Chinese measures increased. Natives were reminded to watch the Chinese and not to engage with them. However in terms of military preparations, little was done.[36]

Koxinga's invasion

Zheng Chenggong, known in Dutch sources as Koxinga, studied at the Imperial Academy in Nanjing. When Beijing fell in 1644 to rebels, Chenggong and his followers declared their loyalty to the Ming dynasty and he was bestowed the title Guoxingye (Lord of the Imperial surname). Chenggong continued the resistance against the Qing from Xiamen. In 1650 he planned a major offensive from Guangdong. The Qing deployed a large army to the area and Chenggong decided to ferry his army along the coast but a storm hindered his movements. The Qing launched a surprise attack on Xiamen, forcing him to return to protect it. From 1656 to 1658 he planned to take Nanjing. Chenggong encircled Nanjing on 24 August 1659. Qing reinforcements arrived and broke Chenggong's army, forcing them to retreat to Xiamen. In 1660 the Qing embarked on a coastal evacuation policy to starve Chenggong of his source of livelihood.[37] Some of the rebels during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion had expected aid from Chenggong and some company officials believed that the rebellion had been incited by him.[37]

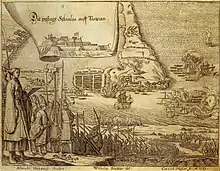

Chenggong retreated from his stronghold in Amoy (Xiamen city) and attacked the Dutch colony in Taiwan in the hope of establishing a strategic base to marshal his troops to retake his base at Amoy. On 23 March 1661, Zheng's fleet set sail from Kinmen with a fleet carrying around 25,000 soldiers and sailors. The fleet arrived at Tayouan on 2 April. Zheng's forces routed 240 Dutch soldiers at Baxemboy Island in the Bay of Taiwan and landed at the bay of Luermen.[38][39] Three Dutch ships attacked the Chinese junks and destroyed several until their main warship exploded. The remaining ships were unable to keep Zheng from controlling the waters around Taiwan.[40][41]

On 4 April, Fort Provintia surrendered to Zheng's forces. Following a nine-month siege, Chenggong captured the Dutch fortress Zeelandia and established a base in Taiwan.[42] The Dutch held out at Keelung until 1668 when they withdrew from Taiwan completely.[43][44][45]

Kingdom of Tungning (1661–1683)

Retreat to Taiwan

Following the death of Zheng Chenggong in 1662, his son Zheng Jing's succession was met with dissension in Taiwan, where the leaders made Zheng Miao, Zheng Chenggong's fifth son, the successor. With the support of Xiamen's commanders, Zheng Jing arrived in Taiwan in December 1662 and defeated his political enemies. The political infighting caused some followers to become disillusioned and defect to the Qing. From September 1661 to August 1662, some 290 officers, 4,334 soldiers, and 467 civilians left Zheng Taiwan. Three leading Zheng commanders contacted Qing authorities with the intention to defect but Zheng Jing imprisoned them. The defections continued and by 1663, some 3,985 officials and officers, 40,962 soldiers, 64,230 civilians, and 900 ships in Fujian had defected from Zheng held territory.[46] To combat population decline, Zheng Jing also promoted migration to Taiwan. Between 1665 and 1669 a large number of Fujianese moved to Taiwan under Zheng rule. In a few years, some 9,000 Chinese were brought to Taiwan by Zheng Jing.[47][48]

The Qing dynasty enacted a sea-ban on coastal China to starve out the Zheng forces. In 1663, the writer Xia Lin who lived in Xiamen testified that the Zhengs were short on supplies and the people suffered tremendous hardship due to the Qing sea ban (haijin) policy. After Zheng forces retreated completely from the coast of Fujian in 1669, the Qing started relaxing restrictions on maritime trade.[49] Due to the sea ban policy, which saw the relocation of all southern coastal towns and ports that had been subject to Zheng raids, migration occurred from these areas to Taiwan. About 1,000 previous Ming government officials moved to Taiwan fleeing Qing persecution.[50]

From June to August 1663, Duke Huang Wu of Haicheng and commander Shi Lang of Tongan urged the Qing court to take Xiamen, and made plans for an attack in October. The Dutch too had attacked Zheng ships in Xiamen but failed to take the town. In August the Dutch contacted Qing authorities in Fujian to propose a joint expedition against Zheng Taiwan. The message did not reach the Qing court until 7 January 1663 and it took another four months for a reply. The Kangxi Emperor granted the Dutch permission to set up inland trading posts but declined the proposal for a joint expedition. The Dutch did however assist the Qing in naval combat against the Zheng fleet in October 1663, resulting in the capture of Zheng bases in Xiamen and Kinmen in November. The Zheng admiral Zhou Quanbin surrendered on 20 November. The remaining Zheng forces fled southward and completely evacuated from the mainland coast in the spring of 1664.[51][52]

Qing-Dutch forces attempted to invade Taiwan twice in December 1664. On both occasions Admiral Shi Lang turned back his ships due to adverse weather. Shi Lang tried to attack Taiwan again in 1666 but turned back due to a storm. The Dutch continued to attack Zheng ships from time to time, disrupting trade, and occupied Keelung until 1668, but they were unable to take back the island. Their position at sea was gradually taken over by Great Britain. On 10 September 1670, a representative from the British East India Company signed a trade agreement with Zheng Taiwan.[53][54] However trade with the British was limited because of the Zheng monopoly on sugar cane and deer hide as well as the inability of the British to match the price of East Asian goods for resale. Zheng trade was subject to the Qing sea ban policy throughout its existence, limiting trade with mainland China to smugglers.[50]

Revolt of the Three Feudatories

In 1670 and 1673, Zheng forces seized tributary vessels on their way to the mainland from Ryukyu. In 1671, Zheng forces raided the coast of Zhejiang and Fujian. In 1674, Zheng Jing took advantage of the Revolt of the Three Feudatories on the mainland and recaptured Xiamen and used it as a trading center to fund his efforts to retake mainland China. He imported swords, gun barrels, knives, armours, lead and saltpeter, and other components for gunpowder. Zheng made an alliance with the rebel lord Geng Jingzhong in Fujian, but they fell afoul of each other not long afterward. Zheng captured Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in 1674. In 1675, the commander of Chaozhou, Liu Jingzhong, defected to Zheng. After Geng and other rebels surrendered to the Qing in 1676 and 1677, the tide turned against the Zheng forces. Quanzhou was lost to the Qing on 12 March 1677 and then Zhangzhou and Haicheng on 5 April. Zheng forces counterattacked and retook Haicheng in August. Zheng naval forces blockaded Quanzhou and tried to retake the city in August 1678 but they were forced to retreat in October when Qing reinforcements arrived. Zheng forces suffered heavy casualties in a battle in January 1679.[55]

On 6 March 1680, the Qing fleet led by Admiral Wan Zhengse moved against Zheng naval forces near Quanzhou and defeated them on 20 March with assistance from land-based artillery. The sudden retreat of Zheng naval forces caused widespread panic on land and many Zheng commanders and soldiers defected to the Qing. Xiamen was abandoned. On 10 April, Zheng Jing's war on the mainland came to a close.[56]

Zheng Jing died in early 1681.[57]

Qing invasion

Shi Lang

.jpg.webp)

Admiral Shi Lang was the primary leader in advocating and organizing the Qing effort to conquer Zheng Taiwan. Born in Jinjiang, Fujian in 1621, he was a soldier in the service of Zheng Zhilong until he had a falling out with Zheng Chenggong, resulting in Shi's defection to the Qing.[58][59]

The Qing established a naval force in Fujian in 1662 and appointed Shi Lang as the commander. On 15 May 1663, Shi attacked the Zheng fleet and succeeded in capturing 24 Zheng officers, 5 ships, and killing over 200 enemies. Shi planned to attack Xiamen on 19 September, but the Qing court decided to postpone the assault until Dutch naval reinforcements arrived. From 18 to 20 November, the Dutch fought sea battles against the Zheng while Shi took Xiamen. In 1664, Shi assembled a fleet of 240 ships, and in conjunction with 16,500 troops, chased the remaining Zheng forces south. They failed to dislodge the last Zheng stronghold due to the departure of the Dutch fleet. However, after the defection of Zheng commander Zhou Quanbin, Zheng Jing decided to pull out from the remaining mainland stronghold in the spring of 1664.[60]

Shi proposed to the Qing court an invasion of Penghu and Taiwan. In November 1664, Shi's fleet set sail but was turned back by a storm. He tried again in May 1665 but there was too little wind to move the ships and then a few days later the winds reversed direction and forced him to return. Another failed attempt was made in June when they were met with a violent storm, sinking a few small ships, and damaging the masts of several other ships. Shi's flagship was blown to the coast of Guangdong on 30 June. In 1666, the Qing called off the expedition.[61] Shi Lang was removed from office in 1667 during negotiations between the Qing and Zheng Taiwan.[62]

Battle of Penghu

Shi Lang was reappointed as the naval chief of Fujian on 10 September 1681.[63]

In Taiwan, Zheng Jing's death resulted in a coup shortly afterward. His illegitimate son, Zheng Keshuang, murdered his brother Zheng Kezang with the support of minister Feng Xifan. Political turmoil, heavy taxes, an epidemic in the north, a large fire that caused the destruction of more than a thousand houses, and suspicion of collusion with the Qing caused more Zheng followers to defect to the Qing. Zheng's deputy Commander Liu Bingzhong surrendered with his ships and men from Penghu.[64][65]

Orders from the Kangxi Emperor to invade Taiwan reached Yao Qisheng and Shi Lang on 6 June 1682. The invasion fleet was met with unfavorable winds and was forced to turn back. Yao proposed a five-month postponement of the invasion to wait for favorable winds in November. Conflict between Yao and Shi led to Yao's removal from power in November.[66]

On 18 November 1682, Shi Lang was authorized to assume the role of supreme commander while Yao was relegated to logistical matters. Supplies arrived for Shi's 21,000 troops, 70 large warships, 103 supply ships, and 65 double mast vessels in early December. Spy ships were sent to scout Penghu and returned safely. Two attempts to sail to Penghu in February 1683 failed due to a shift in winds.[67]

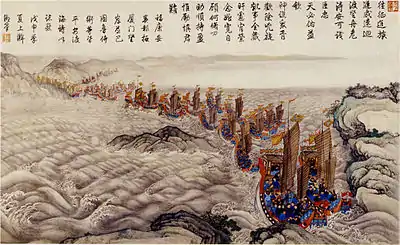

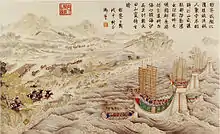

Shi's fleet of 238 ships and over 21,000 men set sail on 8 July 1683. Liu Guoxuan, the commander of 30,000 men at Penghu, considered the movement a false alarm and believed Shi would turn back. The next day, Shi's fleet was sighted at small islands to the northwest of Penghu. The Qing forces were met by 200 Zheng ships. Following an exchange of gunfire, the Qing were forced to retreat with two Zheng naval commanders, Qiu Hui and Jiang Sheng, in pursuit. The Qing vanguard led by Admiral Lan Li provided cover fire for a withdrawal. Shi was hit in the right eye and Lan was wounded in the stomach during the fighting. The Zheng side also suffered heavy losses, making Liu reluctant to pursue the disarrayed Qing forces. He reported a "great victory" back to Taiwan.[68]

On 11 July, Shi regrouped his squadrons and requested reinforcements at Bazhao. On 16 July, a reinforcement of large ships arrived. Shi divided the main striking force into eight squadrons of seven ships with himself leading from the middle. Two flotillas of 50 small ships sailed in two different directions as a diversion. The remaining vessels served as rear reinforcements.[69]

The battle took place in the bay of Magong. The Zheng garrison fired at the Qing ships and then set sail from the harbor with about 100 ships to meet the Qing forces. Shi concentrated fire on one big enemy ship at a time until all of Zheng's battle ships were sunk by the end of 17 July. Liu escaped to Taiwan with dozens of small vessels. Approximately 12,000 Zheng men perished. The garrison commanders surrendered after hearing of Liu's escape. The Qing captured Penghu on 18 July.[70]

Qing dynasty (1683–1895)

.jpg.webp)

Indigenous rebellions (1723–1733)

In 1723, aborigines living in Dajiaxi village along the central coastal plain rebelled. Government troops from southern Taiwan were sent to put down this revolt, but in their absence, Han settlers in Fengshan County rose up in revolt under the leadership of Wu Fusheng, a settler from Zhangzhou.[71] By 1732, five different ethnic groups were in revolt but the rebellion was defeated by the end of the year.[71]

During the Qianlong period (1735–1796), the 93 shufan acculturated aborigine villages never rebelled and over 200 non-acculturated aboriginal villages submitted.[72] In fact, during the 200 years of Qing rule in Taiwan, the plains aborigines rarely rebelled against the government and the mountain aborigines were left to their own devices until the last 20 years of Qing rule. Most of the rebellions, of which there were more than 100 during the Qing period, were caused by Han settlers.[73][74] The idom, "Every three years an uprising, every five years a rebellion" (三年一反、五年一亂), was used primarily to describe commotions that occurred during the 30-year period between 1820-1850.[75][76]

Zhu Yigui rebellion

Zhu Yigui, also known as the "Duck King",[77] was a settler from Fujian. He became the owner of a duck farm in Taiwan's Luohanmen (modern Kaohsiung). Zhu was known among locals for his generous conduct and persistent fight against immoral conduct. In 1720, there was an upset among merchants, fishermen, and farmers in Taiwan due to increased taxation. They gathered around Zhu, who shared the same surname with the Ming dynasty's royal family, and supported him in mobilizing discontent Chinese into an anti-Qing rebellion.[78] Zhu was declared the Ming Emperor and efforts were made to imitate Ming style clothing with performance costumes.[77] Hakka leader Lin Junying from the south also joined the rebellion. In March 1720, Zhu and Lin attacked the Qing garrison at Taiwan County and defeated them in April. In less than two weeks, the rebels had defeated Qing forces in all of Taiwan. The Hakka troops left Zhu to follow Lin north. The Qing sent a fleet under the command of Shi Shibian (son of Shi Lang) with an army of 22,000 troops. A month later, the rebellion was defeated and Zhu was executed in Beijing.[78]

Lin Shuangwen rebellion

In 1786, members of the Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth society) secret society were arrested for failing to make tax payments. The Tiandihui broke into the jail, killed the guards, and rescued their members. When Qing troops were sent into the village and tried to arrest Lin Shuangwen, the leader of the Tiandihui and a settler from Fujian, led his forces to defeat the Qing troops.[79] Many of the rebel army's troops came from new arrivals from mainland China who could not find land to farm. They joined the Tiandihui for protection.[77] Lin attacked Changhua County, killing 2,000 civilians. In early 1787, 50,000 Qing troops under Li Shiyao from the mainland were sent to put down the rebellion. The two sides fought to a stalemate for six months. Lin tried to enlist the support of the Hakka people but not only did they refuse, they sent their troops to support the Qing.[79] Despite the Tiandihui's ostensibly anti-Qing stance, its members were generally anti-government and were not motivated by ethnic or national interest, resulting in social discord and political chaos. Some civilians aided the Qing against the rebels.[77] In 1788, a fresh force of 10,000 Qing troops led by Fuk'anggan and Hailanqa were sent to Taiwan.[80] They successfully defeated the rebellion shortly after arriving. Lin was executed in Beijing in April 1788.[79] The Qianlong Emperor gave Zhuluo County its modern name Chiayi (lit. commendable righteousness) for resisting the rebels.[77]

Colonization of Kavalan

The Gamalan or Kavalan people were situated in modern Yilan County in northeastern Taiwan. It was separated from the western plains and Tamsui (Danshui) by mountains. There were 36 aboriginal villages in the area and the Kavalan people had started paying taxes as early as the Kangxi period (r. 1661–1722), but they were non-acculturated guihua shengfan aborigines. In 1787, a Chinese settler named Wu Sha tried to reclaim land in Gamalan but was defeated by aborigines. The next year, the Tamsui sub-prefect convinced the Taiwan prefect, Yang Tingli, to support Wu Sha. Yang recommended subjugating the natives and opening Gamalan for settlement to the Fujian governor but the governor refused to act due to fear of conflict. In 1797, a new Tamsui sub-prefect issued permit and financial support for Wu to recruit settlers for land reclamation, which was illegal. Wu's successors were unable to register the reclaimed land on government registers. Local officials supported land reclamation but could not officially recognize it.[81]

In 1806 it was reported that a pirate, Cai Qian, was within the vicinity of Gamalan. Taiwan Prefect Yang once again recommended opening up Gamalan, arguing that to abandon it would cause trouble on the frontier. Later another pirate band tried to occupy Gamalan. Yang recommended to the Fuzhou General Saichong'a the establishment of administration and land surveys in Gamalan. Saichong'a initially refused but then changed his mind and sent a memorial to the emperor in 1808 recommending the incorporation of Gamalan. The issue was discussed by the central government officials and for the first time, one official went on record saying that if aboriginal territory was incorporated, not only would it end the pirate threat but the government would stand to profit from the land itself. In 1809, the emperor ordered for Gamalan to be incorporated. The next year an imperial decree for the formal incorporation of Gamalan was issued and a Gamalan sub-prefect was appointed.[82]

Opium War

By 1831, the East India Company decided it no longer wanted to trade with the Chinese on their terms and planned more aggressive measures. A Prussian missionary and linguist, Karl F.A. Gutzlaff, was sent to explore Taiwan. He published his experiences in Taiwan in 1833 confirming its rich resources and trade potential. Given the strategic and commercial value of Taiwan, there were British suggestions in 1840 and 1841 to seize the island. William Huttman wrote to Lord Palmerston pointing out "China’s benign rule over Taiwan and the strategic and commercial importance of the island."[83] He suggested that Taiwan could be occupied with only a warship and less than 1,500 troops, and the English would be able to spread Christianity among the natives as well as develop trade.[84]

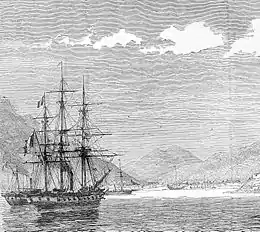

In September 1841, during the First Opium War, the British transport ship Nerbudda became shipwrecked near Keelung Harbour due to a typhoon. The captain and a handful of English officers escaped safely, however most of the crew including 29 Europeans, 5 Filipinos, and 240 Indian lascars, were rescued by locals and handed over to Qing officials in Tainan, the capital of Taiwan. In October 1841, HMS Nimrod sailed to Keelung to search for the Nerbudda survivors, but after Captain Joseph Pearse found out that they were sent south for imprisonment, he ordered the bombardment of the harbour and destroyed 27 sets of cannon before returning to Hong Kong. The brig Ann also shipwrecked in March 1842 and another 54 survivors were taken.The Taiwan Qing commanders, Dahonga and Yao Ying, filed a disingenuous report to the emperor, claiming to have defended against an attack from the Keelung fort. Most of the survivors—over 130 from the Nerbudda and 54 from the Ann—were executed in Tainan in August 1842. The false report was later discovered and the officials in Taiwan punished. The British wanted them executed but they were only given different postings on the mainland, which the British were not aware of until 1845.[83]

Rover incident

On 12 March 1867, the American barque Rover shipwrecked offshore at the southern tip of Taiwan. The vessel sank but the captain, his wife, and some men escaped on two boats. One boat landed at a small bay near the Bi Mountains inhabited by the Koaluts (Guizaijiao) tribe of the Paiwan people. The Koaluts aborigines captured them and mistook the captain's wife for a man. They killed her. The captain, two white men, and the Chinese sailors save for one who managed to escape to Takau, were also killed. The Cormorant, a British steamer, tried to help and landed near the shipwreck on 26 March. The aborigines fired muskets and shot arrows at them, forcing them to retreat. The American Asiatic Fleet's Admiral Bell also landed at the Bi Mountains where they got lost, suffered heatstroke, and then was ambushed by the aborigines, losing an officer.[85][86]

Le Gendre, the US Consul, blamed the Qing dynasty for the failure and demanded that they send troops to help him negotiate with the aborigines. He also hoped that the Qing would permanently station troops to prevent further killings by the aborigines. On 10 September, Garrison Commander Liu Mingcheng led 500 Qing troops to southern Taiwan with Le Gendre. The remains were recovered. The aboriginal chief, Tanketok (Toketok), explained that a long time ago the white men came and almost exterminated the Koaluts tribe and their ancestors passed down their desire for revenge. They came to an oral agreement that the mountain aborigines would not kill any more castaways, would care for them and hand them over to the Chinese at Langqiao.[87]

Le Gendre visited the tribe again in February 1869 and signed an agreement with them in English. It was later discovered that Tanketok did not have absolute control over the tribes and some of them paid him no heed. Le Gendre castigated China as a semi-civilized power for not fulfilling the obligation of the law of nations, which is to seize the territory of a "wild race" and to confer upon it the benefits of civilization. Since China failed to prevent the aborigines from killing subjects or citizens of civilized countries, "we see the rights of the Emperor of China over aboriginal Formosa, such as we have said, are not absolute, as long as she remains uncivilized..."[88] Le Gendre later moved to Japan and worked with the Japanese government as a foreign advisor on their China policy, including the development of the concept of the "East Asian crescent". According to the "East Asian crescent" concept, Japan should control Korea, Taiwan, and Ryukyu to affirm its position in East Asia.[89]

Mudan incident

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan vessel shipwrecked on the southeastern tip of Taiwan and 54 sailors were killed by aborigines. Four tribute ships were returning to the Ryukyu Islands when they were blown off course on 12 December. Two ships were pushed towards Taiwan. One of them landed on Taiwan's western coast and made it back home with the help of Qing officials. The other one crashed into the eastern coast of southern Taiwan near Bayao Bay. There were 69 passengers and 66 managed to make it to shore. They met two Chinese men who told them not to travel inland where the dangerous Paiwan people were.[90]

According to the survivors, the Chinese robbed them and they decided to part ways. On 18 December they headed westward and encountered aboriginal men, presumably Paiwanese. They followed the Paiwanese to a small settlement, Kuskus, where they were given food and water. According to Kuskus local Valjeluk Mavalu, the water was a symbol of protection and friendship. The deposition claims they were robbed by their Kuskus hosts during the night. In the morning they were ordered to stay put while hunters left to search for game to provide a feast. Alarmed by the armed men and rumors of head hunting, the Ryukyuans departed while the hunting party was away. They found shelter in the home of a 73 year old Hakka trading-post serviceman, Deng Tianbao. The Paiwanese men found the Ryukyuans and dragged them out, slaughtering them, while others died in a fight or were caught trying to escape. Nine Ryukyuans hid in Deng's home. They moved to another Hakka settlement Poliac (Baoli) where they found refuge with Deng's son-in-law, Yang Youwang. Yang arranged for the ransom of three men and sheltered the survivors for 40 days before sending them to Taiwan Prefecture (modern Tainan). The Ryukuans headed home in July 1872.[91]

It is uncertain what caused the Paiwanese to murder the Ryukyuans. Some say the Ryukyuans did not understand Paiwanese guest etiquette, they ate and ran, or that their captors could not find ransom and therefore killed them. According to Lianes Punanang, a Mudan local, 66 men who could not understand the local languages entered Kuskus and began taking food and drink, disregarding village boundaries. Efforts to aid the strangers with food and drink strained Kuskus resources. They were finally killed for their misdeeds. The shipwreck and murder of the sailors came to be known as the Mudan incident although it did not take place in Mudan (J. Botan), but at Kuskus (Gaoshifo).[92]

The Mudan incident did not immediately cause any concern in Japan. A few officials knew of it by mid-1872 but it was not until April 1874 that it became an international concern. The repatriation procedure in 1872 was by the books and had been a regular affair for several centuries. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the Qing had settled 401 Ryukyuan shipwreck incidents both on the coast of mainland China and Taiwan. The Ryukyu Kingdom did not ask Japanese officials for help regarding the shipwreck. Instead its king, Shō Tai, sent a reward to Chinese officials in Fuzhou for the return of the 12 survivors.[93]

Japanese invasion (1874)

On 30 August 1872, Sukenori Kabayama, a general of the Imperial Japanese Army, urged the Japanese government to invade Taiwan's tribal areas. The Foreign Minister Sakimitsu Yanagihara believed that the perpetrators of the Mudan incident were "all Taiwan savages beyond Chinese education and law."[94] Japan justified sending an expedition to Taiwan through linguistic interpretation of "化外之民" to mean not part of China. Chinese diplomat Li Hongzhang rejected the claim that the murder of Ryukyuans had anything to do with Japan once he learned of Japan's aspirations.[95] However, after communications between the Qing and Yanagihara, the Japanese took their explanation to mean that the Qing government had not opposed Japan's claims to sovereignty over the Ryukyu Islands, disclaimed any jurisdiction over Aboriginal Taiwanese, and had indeed consented to Japan's expedition to Taiwan.[96] In the eyes of Japan and the foreign advisor Le Gendre, the aborigines were "savages" who had no sovereign or international status, and therefore their territory was "terra nullius", free to be seized for Japan.[97]

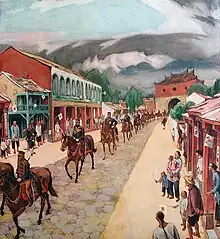

On 9 March 1874, the Taiwan Expedition prepared for its mission. The magistrate of the Taiwan Circuit learned of the impending Japanese invasion from a Hong Kong newspaper quoting a Japanese news item and reported it to Fujian authorities.[98] Qing officials were taken by complete surprise due to the seemingly cordial relations with Japan at the time. On 17 May, Saigō Jūdō led the main force, 3,600 strong, aboard four warships in Nagasaki headed to Tainan.[99] On 6 June, the Japanese emperor issued a certificate condemning the Taiwan "savages" for killing our "nationals", the Ryukyuans killed in southeastern Taiwan.[100]

On 3 May 1874, Kusei Fukushima delivered a note to Fujian-Zhejiang Governor Li Henian announcing that they were heading to savage territory to punish the culprits. On 7 May, a Chinese translator, Zhan Hansheng, was sent ashore to establish peaceful relations with tribes other than the Mudan and Kuskus. Afterwards American foreign officers and Fukushima landed at Checheng and Xinjie. They tried to use Baxian Bay at Qinggangpu as their barracks but heavy rain flooded the site a few days later so the Japanese moved to the southern end of Langqiao Bay on 11 May. They learned that Tanketok had died and invited the Shemali tribe for talks. Japanese scouts fanned out and were met by attacks by aborigines. On 21 May, a 12-member scout party was ambushed and two were wounded. The Japanese camp sent 250 reinforcements and searched the villages. The next day, Samata Sakuma encountered Mudan fighters, around 70 strong, occupying a commanding height. A twenty-men party climbed the cliffs and shot at the Mudan people, forcing them to flee. The Mudan lost 16 men including their tribal leader, Agulu. The Japanese lost seven with 30 injured.[101]

The Japanese army split into three forces and headed in different directions, the south, north, and central routes. The south route army was ambushed by the Kuskus tribe and lost three soldiers. A counterattack defeated the Kuskus fighter and the Japanese burnt their villages. The central route was attacked by Mudan and two or three soldiers were wounded. The Japanese burnt their villages. The north route attacked the Nünai village. On 3 June, they burnt all the villages that had been occupied. On 1 July, the new leader of the Mudan tribe and the chief of Kuskus admitted defeat and promised not to harm shipwrecked castaways.[102] Surrendered aborigines were given Japanese flags to fly over their villages. They were viewed as a symbol of peace with Japan and protection from rival tribes by the aborigines. To the Japanese, it was a symbol of jurisdiction over the aborigines.[103] Chinese forces arrived on 17 June and a report by Fujian Administration Commissioner reported that all 56 representatives of the tribes except for Mudan, Zhongshe and Linai, who were not present due to fleeing from the Japanese, complained about Japanese bullying.[104]

A Chinese representative, Pan Wei, met with Saigō four times between 22 and 26 June but nothing came of it. The Japanese settled in and established large camps with no intention of withdrawing, but in August and September 600 soldiers fell ill. They started dying 15 a day. The death toll rose to 561. Toshimichi Okubo arrived in Beijing on 10 September and seven negotiating sessions occurred over a month long period. The Western Powers pressured China not to cause bloodshed with Japan as it would negatively impact the coastal trade. The resulting Peking Agreement was signed on 30 October. Japan gained the recognition of Ryukyu as its vassal and an indemnity payment of 500,000 taels. Japanese troops withdrew from Taiwan on 3 December.[105]

Sino-French War

During the Sino-French War, the French invaded Taiwan during the Keelung Campaign in 1884. The Chinese had already been aware of French plans to attack Taiwan and sent Liu Mingchuan, the governor of Fujian, to strengthen Taiwan's defenses on 16 July. On 5 August 1884, Sébastien Lespès bombarded Keelung's harbor and destroyed the gun placements. The next day, the French attempted to take Keelung but failed to defeat the larger Chinese force led by Liu Mingchuan and were forced to withdraw to their ships. On 1 October, Amédée Courbet landed with 2,250 French forces and defeated a smaller Chinese force, though equipped with Krupp guns, capturing Keelung. French efforts to capture Tamsui failed. The port of Tamsui had been filled with debris by the Chinese and the French were unable to sustain a landing. The French shelled Tamsui, destroying not only the forts but also foreign buildings. Some 800 French troops landed on Shalin beach near Tamsui but they were repelled by Chinese forces.[106]

The French imposed a blockade on Taiwan from 23 October 1884 until April 1885 but the execution was not completely effective. Foreign vessels were barred from docking in blockaded harbors. Some believed that the blockade was almost directed at the British. The French did not have enough ships to impose a complete blockade on Taiwan and only concentrated on the major ports, leaving smaller Chinese vessels to enter lesser ports with troops and supplies. The first Chinese relief effort, a fleet of five ships, was repelled by the French with two ships sunk. On 21 December 1884, five battalions in southern China were ordered to reinforce Taiwan.[107] French ships around mainland China's coast attacked any junk they could find and captured its occupants to be shipped to Keelung for constructing defensive works. However the blockade failed to stop Chinese junks from reaching Taiwan. For every junk the French captured, another five junks arrived with supplies at Takau and Anping. The immediate effect of the blockade was a sharp decline in legal trade and income.[108]

In late January 1885, Chinese forces suffered a serious defeat around Keelung. Although the French captured Keelung they were unable to move beyond its perimeters. In March the French tried to take Tamsui again and failed. At sea, the French bombarded Penghu on 28 March.[109] Penghu surrendered on 31 March but many of the French soon grew ill and 1,100 soldiers and later 600 more were debilitated. The French commander died from illness in Penghu.[110]

An agreement was reached on 15 April 1885 and an end to hostilities was announced. The French evacuation from Keelung was completed on 21 June 1885 and Penghu remained under Chinese control.[111]

Liu Mingchuan's colonization campaign

After the Sino-French War, efforts to settle in aboriginal territories were renewed under the governance of Liu Mingchuan, the Fujian governor and Taiwan defense commissioner. Administering Taiwan became his sole focus in 1885 and the administration of Fujian was left to the governor-general. Another prefecture, Taiwan Prefecture, was created in the western plains, while the former Taiwan Prefecture was renamed Tainan. Three new counties were created, a new Taitung Department (eastern Taiwan department) was created, and in the subsequent years, three new subprefectures were added.[112] In 1887, Taiwan became its own province.[113]

A Taiwan Pacification and Reclamation Head Office was established with eight pacification and reclamation bureaus. Four bureaus were located in eastern Taiwan, two in Puli (inner Shuishalian), one in the north, and one on the western border of the mountains. By 1887, about 500 aboriginal villages, or roughly 90,000 aborigines had formally submitted to Qing rule. This number increased to 800 villages with 148,479 aborigines over the following years. However the cost of getting them to submit was exorbitant. The Qing offered them materials and paid village chiefs monthly allowances. Not all the aborigines were under effective control and land reclamation in eastern Taiwan occurred at a slow pace.[114] From 1884 to 1891, Liu launched more than 40 military campaigns against the aborigines with 17,500 soldiers. The eastward expansion ended after the defeat of the Mkgogan and Msbtunux due to the fierceness of their resistance. A third of the invasion force was killed or disabled in the conflict, amounting to a costly failure.[115][116]

Sino-Japanese War

As part of the settlement for losing the Sino-Japanese War, the Qing dynasty ceded the islands of Taiwan and Penghu to Japan on April 17, 1895, according to the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The loss of Taiwan would become a rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed.[117] The pro-Qing officials and elements of the local gentry declared an independent Republic of Formosa in 1895, but failed to win international recognition. The Japanese spent the next twenty years fighting rebellions in Taiwan while encouraging Japanese colonists to settle there. However, due to lack of infrastructure and fear of disease such as leprosy and malaria, few moved to Taiwan in the early years.[118]

Japanese Empire (1895–1945)

Invasion and suppression

The colonial authorities encountered violent opposition in much of Taiwan. Five months of sustained warfare occurred after the invasion of Taiwan in 1895 and partisan attacks continued until 1902. For the first two years the colonial authority relied mainly on military force and local pacification efforts. Disorder and panic were prevalent in Taiwan after Penghu was seized by Japan in March 1895. On 20 May, Qing officials were ordered to leave their posts. General mayhem and destruction ensued in the following months.[119]

Japanese forces landed on the coast of Keelung on 29 May and Tamsui's harbor was bombarded. Remnant Qing units and Guangdong irregulars briefly fought against Japanese forces in the north. After the fall of Taipei on 7 June, local militia and partisan bands continued the resistance. In the south, a small Black Flag force led by Liu Yongfu delayed Japanese landings. Governor Tang Jingsong attempted to carry out anti-Japanese resistance efforts as the Republic of Formosa, however he still professed to be a Qing loyalist. The declaration of a republic was, according to Tang, to delay the Japanese so that Western powers might be compelled to defend Taiwan.[119] The plan quickly turned to chaos as the Green Standard Army and Yue soldiers from Guangxi took to looting and pillaging Taiwan. Given the choice between chaos at the hands of bandits or submission to the Japanese, Taipei's gentry elite sent Koo Hsien-jung to Keelung to invite the advancing Japanese forces to proceed to Taipei and restore order.[120] The Republic, established on 25 May, disappeared 12 days later when its leaders left for the mainland.[119] Liu Yongfu formed a temporary government in Tainan but escaped to the mainland as well as Japanese forces closed in.[121] Between 200,000 and 300,000 people fled Taiwan in 1895.[122][123] Chinese residents in Taiwan were given the option of selling their property and leaving by May 1897, or become Japanese citizens. From 1895 to 1897, an estimated 6,400 people, mostly gentry elites, sold their property and left Taiwan. The vast majority did not have the means or will to leave.[124][125][126]

Upon Tainan's surrender, Kabayama declared Taiwan pacified, however his proclamation was premature. In December, a series of anti-Japanese uprisings occurred in northern Taiwan, and would continue to occur at a rate of roughly one per month. Armed resistance by Hakka villagers broke out in the south. A series of prolonged partisan attacks, led by "local bandits" or "rebels", lasted throughout the next seven years. After 1897, uprisings by Chinese nationalists were commonplace. Luo Fuxing, a member of the Tongmenghui organization preceding the Kuomintang, was arrested and executed along with two hundred of his comrades in 1913.[127] Japanese reprisals were often more brutal than the guerilla attacks staged by the rebels. In June 1896, 6,000 Taiwanese were slaughtered in the Yunlin Massacre. From 1898 to 1902, some 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed in addition to the 6,000–14,000 killed in the initial resistance war of 1895.[121][128][129] During the conflict, 5,300 Japanese were killed or wounded, and 27,000 were hospitalized.[130]

Rebellions were often caused by a combination of unequal colonial policies on local elites and extant millenarian beliefs of the local Taiwanese and plains indigenous.[131] Ideologies of resistance drew on different ideals such as Taishō democracy, Chinese nationalism, and nascent Taiwanese self-determination.[117] Support for resistance was partly class-based and many of the wealthy Han people in Taiwan preferred the order of colonial rule to the lawlessness of insurrection.[132]

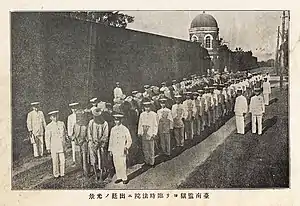

Major armed resistance was largely crushed by 1902 but minor rebellions started occurring again in 1907, such as the Beipu uprising by Hakka and Saisiyat people in 1907, Luo Fuxing in 1913 and the Tapani Incident of 1915.[131][133] The Beipu uprising occurred on 14 November 1907 when a group of Hakka insurgents killed 57 Japanese officers and members of their family. In the following reprisal, 100 Hakka men and boys were killed in the village of Neidaping.[134] Luo Fuxing was an overseas Taiwanese Hakka involved with the Tongmenghui. He planned to organize a rebellion against the Japanese with 500 fighters, resulting in the execution of more than 1,000 Taiwanese by Japanese police. Luo was killed on 3 March 1914.[128][135] In 1915, Yu Qingfang organized a religious group that openly challenged Japanese authority. Indigenous and Han forces led by Chiang Ting and Yu stormed multiple Japanese police stations. In what is known as the Tapani incident, 1,413 members of Yu's religious group were captured. Yu and 200 of his followers were executed.[136] After the Tapani rebels were defeated, Andō Teibi ordered Tainan's Second Garrison to retaliate through massacre. Military police in Tapani and Jiasian announced that they would pardon any anti-Japanese militants and that those who had fled into the mountains should return to their village. Once they returned, the villagers were told to line up in a field, dig holes, and were then executed by firearm. According to oral tradition, at least 5,000–6,000 people died in this incident.[137][138][139]

Indigenous people's resistance

Indigenous resistance to the heavy-handed Japanese policies of acculturation and pacification lasted up until the early 1930s.[131] By 1903, indigenous rebellions had resulted in the deaths of 1,900 Japanese in 1,132 incidents.[132] In 1911 a large military force invaded Taiwan's mountainous areas to gain access to timber resources. By 1915, many indigenous villages had been destroyed. The Atayal and Bunun resisted the hardest against colonization.[140] The Bunun and Atayal were described as the "most ferocious" indigenous peoples, and police stations were targeted by indigenous in intermittent assaults.[141]

The Bunun under Chief Raho Ari engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese for twenty years. Raho Ari's revolt, called the Taifun Incident was sparked when the Japanese implemented a gun control policy in 1914 against the indigenous peoples in which their rifles were impounded in police stations when hunting expeditions were over. The revolt began at Taifun when a police platoon was slaughtered by Raho Ari's clan in 1915. A settlement holding 266 people called Tamaho was created by Raho Ari and his followers near the source of the Rōnō River and attracted more Bunun rebels to their cause. Raho Ari and his followers captured bullets and guns and slew Japanese in repeated hit and run raids against Japanese police stations by infiltrating over the Japanese "guardline" of electrified fences and police stations as they pleased.[142] As a result, head hunting and assaults on police stations by indigenous still continued after that year.[143][144] In one of Taiwan's southern towns nearly 5,000 to 6,000 were slaughtered by Japanese in 1915.[145]

As resistance to the long-term oppression by the Japanese government, many Taivoan people from Kōsen led the first local rebellion against Japan in July 1915, called the Jiasian Incident (Japanese: 甲仙埔事件, Hepburn: Kōsenpo jiken). This was followed by a wider rebellion from Tamai in Tainan to Kōsen in Takao in August 1915, known as the Seirai-an Incident (Japanese: 西来庵事件, Hepburn: Seirai-an jiken) in which more than 1,400 local people died or were killed by the Japanese government. Twenty-two years later, the Taivoan people struggled to carry on another rebellion; since most of the indigenous people were from Kobayashi, the resistance taking place in 1937 was named the Kobayashi Incident (Japanese: 小林事件, Hepburn: Kobayashi jiken).[146] Between 1921 and 1929 indigenous raids died down, but a major revival and surge in indigenous armed resistance erupted from 1930 to 1933 for four years during which the Musha incident occurred and Bunun carried out raids, after which armed conflict again died down.[147] The 1930 "New Flora and Silva, Volume 2" said of the mountain indigenous that "the majority of them live in a state of war against Japanese authority".[148]

The last major indigenous rebellion, the Musha Incident, occurred on 27 October 1930 when the Seediq people, angry over their treatment while laboring in camphor extraction, launched the last headhunting party. Groups of Seediq warriors led by Mona Rudao attacked policed stations and the Musha Public School. Approximately 350 students, 134 Japanese, and 2 Han Chinese dressed in Japanese garbs were killed in the attack. The uprising was crushed by 2,000–3,000 Japanese troops and indigenous auxiliaries with the help of poison gas. The armed conflict ended in December when the Seediq leaders committed suicide. According to Japanese colonial records, 564 Seediq warriors surrendered and 644 were killed or committed suicide.[149][150] The incident caused the government to take a more conciliatory stance towards the indigenous, and during World War 2, the government tried to assimilate them as loyal subjects.[151] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the war against the indigenous numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[152] According to a 1935 report, 7,081 Japanese were killed in the armed struggle from 1896 to 1933 while the Japanese confiscated 29,772 Aboriginal guns by 1933.[153]

World War II

War

As Japan embarked on full-scale war with China in 1937, it expanded Taiwan's industrial capacity to manufacture war material. By 1939, industrial production had exceeded agricultural production in Taiwan. The Imperial Japanese Navy operated heavily out of Taiwan. The "South Strike Group" was based out of the Taihoku Imperial University (now National Taiwan University) in Taiwan. Taiwan was used as a launchpad for the invasion of Guangdong in late 1938 and for the occupation of Hainan in February 1939. A joint planning and logistical center was established in Taiwan to assist Japan's southward advance after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.[154] Taiwan served as a base for Japanese naval and air attacks on the island Luzon until the surrender of the Philippines in May 1942. It also served as a rear staging ground for further attacks on Myanmar. As the war turned against Japan in 1943, Taiwan suffered due to Allied submarine attacks on Japanese shipping, and the Japanese administration prepared to be cut off from Japan. In the latter part of 1944, Taiwan's industries, ports, and military facilities were bombed in U.S. air raids.[155] By the end of the war in 1945, industrial and agricultural output had dropped far below prewar levels, with agricultural output 49% of 1937 levels and industrial output down by 33%. Coal production dropped from 200,000 metric tons to 15,000 metric tons.[156] An estimated 16,000–30,000 civilians died from the bombing.[157] By 1945, Taiwan was isolated from Japan and its government prepared to defend against an expected invasion.[155]

During WWII the Japanese authorities maintained prisoner of war camps in Taiwan. Around 4,350 Allied prisoners of war (POW) were used as forced labor in camps throughout Taiwan between 1942 and 1945. The camp served the copper mines at Jinguashi being especially heinous.[158] Of the 430 Allied POW deaths across all fourteen Japanese POW camps on Taiwan, the majority occurred at Jinguashi.[159]

Taiwanese military servicemen

Starting in July 1937, Taiwanese began to play a role on the battlefield, initially in noncombatant positions. Taiwanese people were not recruited for combat until late in the war. In 1942, the Special Volunteer System was implemented, allowing even aborigines to be recruited as part of the Takasago Volunteers. From 1937 to 1945, over 207,000 Taiwanese were employed by the Japanese military. Roughly 50,000 went missing in action or died, another 2,000 were disabled, 21 were executed for war crimes, and 147 were sentenced to imprisonment for two or three years.[160][161]

Some Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers claim they were coerced and did not choose to join the army. Accounts range from having no way to refuse recruitment, to being incentivized by the salary, to patriotism for Japan.[162] In one account, a man named Chen Chunqing said he was motivated by his desire to fight the British and Americans but became disillusioned after being sent to China and tried to defect, although the effort was fruitless.[163] Racial discrimination was commonplace despite rare occasions of camaraderie. Some experienced greater equality during their time in the military. One Taiwanese serviceman recalled being called "chankoro" (Qing slave)[164] by a Japanese soldier.[163]

After Japan's surrender, the Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers were abandoned by Japan and no transportation back to Taiwan or Japan was provided. Many of them faced difficulties in mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan due to anti-rightist and anti-communist campaigns in addition to accusations of taking part in the February 28 incident. In Japan they were faced with ambivalence. An organization of Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers tried to get the Japanese government to pay their unpaid wages several decades later. They failed.[165]

Only after a petition in 1987 was a decision made to offer 2 million yen to former Taiwanese soldiers who had suffered severe injury in battle and to the families of those who died. The 2 million yen per claim, a minute fraction of that paid to Japanese soldiers, amounted to very little of the unpaid military salary as a result of inflation according to the organization's calculations. The Japanese government refused to take into account the calculations and refused to pay the wartime debts. Nor did they offer an annual allowance like that paid to Japanese soldiers. According to one Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldier, Chen Junqing, he was very shocked by his trip to Japan in 1973. He had believed he would be warmly welcomed as a soldier who fought for the emperor.[166] One Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldier, Teng Sheng, had difficulty obtaining his injury record from the Japanese and even afterward he was still refused compensation for his injuries.[167][168]

Republic of China and martial law (1945–1987)

On 26 July 1945, the United States, United Kingdom, and Republic of China jointly released the Potsdam Declaration, calling for Japan's surrender. Under the terms, Japan was to be reduced to her pre-1894 territory and stripped of her pre-war empire including Korea and Taiwan, as well as all her recent conquests. On 15 August, Emperor Hirohito announced the Japan’s unconditional surrender. On 2 September, the surrender was formalized in the Japanese Instrument of Surrender.

On 25 October 1945, Governor-General Rikichi Andō handed over the administration of Taiwan and the Penghu islands to Kuomintang official Chen Yi, who accepted the surrender on behalf of the Allied forces under the authorization of General Douglas MacArthur’s General Order No. 1.

As part of the Treaty of San Francisco signed in 1951, “Japan renounces all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores.” Though the legal status of Taiwan remained undetermined, the treaty’s travaux préparatoires showed a consensus among the states present at the San Francisco Peace Conference that this status would be resolved at a later time in accordance with the principles of peaceful settlement of disputes and self-determination.[169]

Modern era

When the United States Congress enacted the Foreign Relations Authorization Act for FY 2003 on 30 September 2002, it required that Taiwan be "treated as though it were designated a major non-NATO ally." The Bush administration subsequently submitted a letter to Congress on 29 August 2003, designating Taiwan as an MNNA.[170]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, public interest in civil defense saw a resurgence due to the threat from China. As of 2022, the Taiwanese civil defense units had 420,000 registered volunteers.[171] In 2023, training shifted to more of a wartime focus with 70% of exercises dedicated to wartime scenarios and 30% of exercises dedicated to natural disaster scenarios, from a previous 50–50 split.[172] Private organizations like Kuma Academy and Forward Alliance provide civil defense and disaster response training to civilians in Taiwan.[173][174][175]

In September 2023, President Tsai Ing-wen launched Taiwan's first domestically built submarine into the harbor of Kaohsiung. The submarine, named Haikun (Chinese: 海鯤), cost $1.54 billion and was set to be delivered to the Republic of China Navy by the end of 2024. The goal of Taiwan's domestic submarine program, according to the head of the program Huang Shu-kuang, was to fend off any attempt from China to encircle Taiwan for an invasion or impose a naval blockade. The Haikun uses a Lockheed Martin combat system and will carry American-made torpedoes.[176]

In 2023, China deployed 1,709 military jets into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone, compared to 1,738 in 2022 and 972 in 2021. Analysts see the flights as a form of gray-zone activity.[177]

See also

References

- ↑ Knapp, Ronald G. (1980). China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. The University of Hawaii. p. 5.

- ↑ Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2012), Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty: His Life, Times, and Legacy, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-8268-1

- ↑ Tanaka Fumio 田中史生 (2008). "Kodai no Amami Okinawa shotō to kokusai shakai" 古代の奄美・沖縄諸島と国際社会. In Ikeda Yoshifumi (ed.). Kodai chūsei no kyōkai ryōiki 古代中世の境界領域. pp. 49–70.

- ↑ Isorena 2004.

- ↑ Liu 2012, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Hsu 1980, p. 6.

- ↑ Wills 2007, p. 86.

- ↑ "歷史沿革". 澎湖縣政府全球資訊網. Penghu County Government. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2023-12-19.

- ↑ Knapp 1980, p. 8.

- ↑ Hsu 1980, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Hang 2015, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Andrade 2008, ch. 6.

- ↑ Jenco, Leigh K. (2020). "Chen Di's Record of Formosa (1603) and an Alternative Chinese Imaginary of Otherness". The Historical Journal. 64: 17–42. doi:10.1017/S0018246X1900061X. S2CID 225283565.

- ↑ "閩海贈言". National Central Library (in Chinese). p. 26. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

萬曆壬寅臘月初旬,將軍沈有容率師渡海,破賊東番。海波盪定,除夕班師

- ↑ Thompson 1964, p. 178.

- ↑ Thompson 1964, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Jansen, Marius B. (1992). China in the Tokugawa World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-06-7411-75-32

- ↑ Recent Trends in Scholarship on the History of Ryukyu's Relations with China and Japan Gregory Smits, Pennsylvania State University, p.13 Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ilha Formosa: the Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century". National Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Borao Mateo (2002), pp. 2–9.

- ↑ Andrade 2008a.

- ↑ Davidson 1903. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDavidson1903 (help)

- ↑ Blussé 2000, p. 144–145.

- ↑ Blussé 2000.

- ↑ van Veen (2003), p. 142.

- ↑ Shepherd (1993), p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Andrade 2008b.

- ↑ van Veen (2003), p. 149.

- ↑ Blusse & Everts (2000).

- ↑ Everts (2000), pp. 151–155.

- ↑ Lee, Yuchung. "荷西時期總論 (Dutch and Spanish period of Taiwan)". Council for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ↑ Andrade 2008g.

- ↑ Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects: tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1887893. OL 6931635M.

- ↑ Cheung, Han (20 August 2017). "Taiwan in Time: When colonial powers collide". Taipei Times. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ↑ Andrade 2008h.

- ↑ Andrade 2008i.

- 1 2 Andrade 2008j.

- ↑ Clodfelter (2017), p. 63.

- ↑ Campbell (1903), p. 544.

- ↑ Andrade 2011, p. 138.

- ↑ Campbell (1903), p. 482.

- ↑ Clements (2004), pp. 188–201.

- ↑ Blussé, Leonard (1 January 1989). "Pioneers or cattle for the slaughterhouse? A rejoinder to A.R.T. Kemasang". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 145 (2): 357. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003260. S2CID 57527820.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 207.

- ↑ Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1316453841.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 110.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 106.

- ↑ Lin, A.; Keating, J. (2008). Island in the Stream : A Quick Case Study of Taiwan's Complex History (4th ed.). Taipei: SMC Pub. ISBN 9789576387050. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 109.

- 1 2 Wills, John E. Jr. (2006). "The Seventeenth-century Transformation: Taiwan under the Dutch and the Cheng Regime". In Rubinstein, Murray A. (ed.). Taiwan: A New History. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 84–106. ISBN 9780765614957.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 111–113.

- ↑ Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c. 1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1316453841. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 113–114.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 138.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 118–122.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 124–125.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 157.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 144–147.

- ↑ Twitchett 2002, p. 146.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 148–150.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 150–151.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 152–153.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 155–158.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 166–167.

- ↑ Copper, John F. (2000). Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China) (2nd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780810836655. OL 39088M.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 162–163.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 165–166.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 168–169.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 169–170.

- ↑ Wong 2017, p. 170–171.

- 1 2 Twitchett 2002, p. 228.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 91.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 106.

- ↑ van der Wees, Gerrit. "Has Taiwan Always Been Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ Skoggard, Ian A. (1996). The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: The Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781563248467. OL 979742M. p. 10

- ↑ 民變 [Civil Strife]. Encyclopedia of Taiwan (台灣大百科). Taiwan Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021. 臺灣有「三年一小反,五年一大反」之謠。但是根據研究,這句俗諺所形容民變迭起的現象,以道光朝(1820-1850)的三十多年間為主 [The rumor of "every three years a small uprising, five years a large rebellion" circulated around Taiwan. According to research, the repeated commotions described by this idiom occurred primarily during the 30-year period between 1820 and 1850.].

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Taiwan in Time: Rebels of heaven and earth – Taipei Times". 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- 1 2 Li 2019, p. 82–83.

- 1 2 3 Standaert 2022, p. 225.

- ↑ Li 2019, p. 83.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 56.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 56–57.

- 1 2 Shih-Shan Henry Tsai (2009). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West. Routledge. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-317-46517-1. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ Leonard H. D. Gordon (2007). Confrontation Over Taiwan: Nineteenth-Century China and the Powers. Lexington Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7391-1869-6. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 56.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 119.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 119–120.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 121–122.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 123.

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 50.

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 51–52.

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 52.

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 53–54.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 124–126.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 127–128.

- ↑ Leung (1983), p. 270.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 185–186.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 129.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 132.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 130.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 134–137.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 137–138.

- ↑ "| of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan | the American Historical Review, 107.2 | the History Cooperative". Archived from the original on 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 138.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 141–143.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 142–145.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 146–49.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 149–151, 154.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 149–151.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 161–162.

- ↑ Gordon 2007, p. 162.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 64–65.

- ↑ Rubinstein 1999, p. 187–190.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 65.

- ↑ Rubinstein 1999, p. 191.

- ↑ Cheung, Han (2 May 2021). "Taiwan in Time: The fall of the northern Atayal". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- 1 2 Zhang (1998), p. 514.

- ↑ Matsuda 2019, p. 103–104.

- 1 2 3 Rubinstein 1999, p. 205–206.

- ↑ Morris (2002), pp. 4–18.

- 1 2 Rubinstein 1999, p. 207.

- ↑ Wang 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 561. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDavidson1903 (help)

- ↑ Rubinstein 1999, p. 208.

- ↑ Brooks 2000, p. 110.

- ↑ Dawley, Evan. "Was Taiwan Ever Really a Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ↑ Zhang (1998), p. 515.

- 1 2 Chang 2003, p. 56.

- ↑ "Taiwan – History". Windows on Asia. Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-22.

- ↑ Rubinstein 1999, p. 207–208.

- 1 2 3 Katz (2005).

- 1 2 Price 2019, p. 115.

- ↑ Huang-wen lai (2015). "The turtle woman's voices: Multilingual strategies of resistance and assimilation in Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule" (pdf published=2007). p. 113. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ Lesser Dragons: Minority Peoples of China. Reaktion Books. 15 May 2018. ISBN 9781780239521.

- ↑ Place and Spirit in Taiwan: Tudi Gong in the Stories, Strategies and Memories of Everyday Life. Routledge. 29 August 2003. ISBN 9781135790394.

- ↑ Tsai 2009, p. 134.

- ↑ Wang 2000, p. 113.

- ↑ Su 1980, p. 447–448.

- ↑ "Governmentality and Its Consequences in Colonial Taiwan: A Case Study of the Ta-pa-ni Incident" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2007.

- ↑ Rubinstein 1999, p. 211–212.

- ↑ The Japan Year Book 1937 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 1004.

- ↑ Crook 2014 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 16.

- ↑ The Japan Year Book 1937 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 1004.

- ↑ ed. Inahara 1937, p. 1004.

- ↑ Tay-sheng Wang (28 April 2015). Legal Reform in Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule, 1895–1945: The Reception of Western Law. University of Washington Press. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-295-80388-3. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ↑ 種回小林村的記憶 : 大武壠民族植物暨部落傳承400年人文誌 (A 400-Year Memory of Xiaolin Taivoan: Their Botany, Their History, and Their People). Kaohsiung City: 高雄市杉林區日光小林社區發展協會 (Sunrise Xiaolin Community Development Association). 2017. ISBN 978-986-95852-0-0.

- ↑ ed. Lin 1995 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 84.

- ↑ ed. Cox 1930 Archived April 10, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 94.

- ↑ Matsuda 2019, p. 106.

- ↑ Ching (2001), pp. 137–140.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 193.

- ↑ The Japan Year Book 1933, p. 1139.

- ↑ Japan's progress number ... July 1935 Archived February 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 19.

- ↑ Rubinstein 1999, p. 235.

- 1 2 Rubinstein 1999, p. 235–236.

- ↑ "歷史與發展 (History and Development)". Taipower Corporation. Archived from the original on 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ↑ Economic Development of Emerging East Asia: Catching up of Taiwan and South Korea. Anthem Press. 27 September 2017. ISBN 9781783086887.

- ↑ Sui, Cindy (June 15, 2021). "WW2: Unearthing Taiwan's forgotten prisoner of war camps". BBC News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ Prentice, David (30 October 2015). "The Forgotten POWs of the Pacific: The Story of Taiwan's Camps". Thinking Taiwan. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ↑ Chen 2001, p. 182.

- ↑ Cheung, Han (16 September 2018). "Taiwan in Time: Abandoned by the rising sun". Taipei Times. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ Chen 2001, p. 183–184.

- 1 2 Chen 2001, p. 186–187.

- ↑ Shih 2022, p. 327.

- ↑ Chen 2001, p. 192–195.

- ↑ Chen 2001, p. 194-195.

- ↑ "Taiwan in Time: Abandoned by the rising sun – Taipei Times". 16 September 2018.

- ↑ Okubo, Maki (12 September 2020). "Ex-soldier wants memorial erected for Taiwanese war dead". Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ↑ Chen, Lung-chu (2016). The U.S.-Taiwan-China Relationship in International Law and Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0190601126.

- ↑ Kan, Shirley (December 2009). Taiwan: Major U.S. Arms Sales Since 1990. DIANE Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4379-2041-3.

- ↑ "Civil defense reform needed, experts say". Taipei Times. 26 January 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Yu, Matt; Yang, Evelyn (12 April 2023). "Taiwan to stage the year's first civil defense drill in Taichung". Focus Taiwan. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Wang, Joyu (4 March 2022). "In Taiwan, Russia's War in Ukraine Stirs New Interest in Self-Defense". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ↑ Davidson, Helen (22 September 2021). "Second line of defence: Taiwan's civilians train to resist invasion". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Kwan, Rhoda; Jett, Jennifer. "China is not about to invade Taiwan, experts say, but both are watching Ukraine". NBC News. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ↑ Wong, Tessa (28 September 2023). "Haikun: Taiwan unveils new submarine to fend off China". BBC. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ McCartney, Micah (5 January 2024). "China Deployed Over 1,700 Military Planes Around Taiwan in 2023". Newsweek. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2008). How Taiwan Became Chinese (Project Gutenberg ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12855-1.

- ——— (2011), Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China's First Great Victory Over the West (illustrated ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14455-9

- ——— (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7

- Andrade, Tonio (2008a), "Chapter 1: Taiwan on the Eve of Colonization", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press