.jpg.webp)

Mishaguji (ミシャグジ), also known as Misakuji(n), Mis(h)aguchi or Mishakuji among other variants (see below), is a deity or spirit, or several, that featured in certain religious rites formerly practiced in the Upper Shrine of Suwa, one of the two shrines that comprise the Suwa Grand Shrine complex in Nagano Prefecture (historical Shinano Province). In such ceremonies, the Mishaguji were 'summoned' by one of the shrine's high-ranking priests, the Kan-no-Osa (神長, also Jinchō) or Jinchōkan (神長官), into persons or objects that would act as their vessels (yorishiro) for the duration of the ritual, being then 'dismissed' upon its completion.

In addition to playing a role in Suwa Shrine's religious rites, the Mishaguji are also enshrined in 'Mishaguji Shrines' (御社宮司社 Mishaguji-sha) found throughout the Lake Suwa region and its vicinity. Worship of kami with similar-sounding names are also attested in various localities throughout east and central Japan. Such deities have been speculated to be related to the Mishaguji.

The exact nature of the Mishaguji is a matter of debate. Medieval documents from the Upper Shrine seem to imply them to be lesser gods or spirits subordinate to the shrine's deity, Suwa Daimyōjin (a.k.a. Takeminakata), with post-medieval sources conflating them with Suwa Daimyōjin's children. The term 'Mishaguji' was often interpreted as an epithet of these gods during the early modern period. Outside of Suwa Shrine, the Mishaguji were also worshiped as, god(s) of boundaries and tutelary protectors (ubusunagami) of local communities. In this regard they are functionally similar to the guardian gods known as Dōsojin or Sai-no-kami.

Upon becoming the focus of intense study during the modern period (especially during the postwar era), various theories as to the origins and original nature of Mishaguji worship and its relation to Suwa Shrine began to be put forward by local historians and other scholars. One theory, for instance, claims that they were originally deities of fertility or agriculture, another proposes that the Mishaguji were viewed as spirits that inhabited sacred rocks or trees, while yet another claims that 'Mishaguji' originally denoted an impersonal, empowering force in present in nature analogous to the Austronesian concept of mana.

As phallic stone rods (石棒 sekibō) dating from the Jōmon period and similar prehistoric artifacts are employed as cult objects (shintai) in some Mishaguji-related shrines in Suwa and other areas, a number of authors have speculated that Mishaguji worship may ultimately originate from Jōmon religious beliefs. A few even surmise that the Mishaguji were already being worshiped in Suwa before the cult of Takeminakata - claimed here to be a later import - was introduced into the region; the appearance of the Mishaguji in the Upper Shrine's rites are seen by these scholars to be a relic of original local beliefs. These assumptions, however, have recently come into question.

Names

Multiple variants of the name 'Mishaguji' exist such as 'Mishaguchi', 'Misaguchi', 'Misaguji', 'Mishakuji', 'Misakuji(n)', or 'Omishaguji'.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] There are also various ways of rendering the name in kanji such as 御左口神, 御作神, 御社宮神, or 御社宮司, with 御左口神 being the commonly used form in medieval documents penned by the Suwa Shrine priesthood.[8] Outside Suwa, deities thought to be related to the Mishaguji with names such as '(O)shaguji', '(O)shagoji', '(O)sangūji', 'Sa(n)goji', 'Saguji', 'Shagottsan', 'Shagottan', 'Jogu-san', 'Osangū-san', 'Oshamotsu-sama', or 'Oshamoji-sama' - with different ways of writing them in kanji - are found.[1][9]

The name's etymology is uncertain. During the early modern period when the Mishaguji were conflated with the divine children (mikogami) of Takeminakata, the god of the Upper Suwa Shrine, the name was explained as being derived from the term sakuchi (闢地, lit. 'to open up / develop the land'), which in turn was connected with legends that credit Takeminakata's offspring with forming and developing the land of Shinano.[10][11] The name has also been interpreted as deriving from shakujin / ishigami (石神 'stone deity'), a term used for sacred stones or rocks that were worshiped as repositories (shintai) of kami (it has been observed that stones or stone items were employed as shintai in many Mishaguji-related shrines), or shakujin (尺神), due to another association with bamboo poles and measuring ropes used in land surveying and boundary marking.[7][12] The term sakujin (作神 'harvest / crop deity') has also been suggested as a possible origin.[13] Ōwa Iwao (1990) meanwhile theorized the name to be derived from (mi)sakuchi (honorific prefix 御 mi- + 作霊, 咲霊 sakuchi), a spirit (chi; cf. ikazu-chi, oro-chi, mizu-chi) that brings forth or opens up (saku, cf. 咲く 'to bloom', 裂く 'to tear open', 作 'to do/make/cultivate/grow';cf. also the verb sakuru/shakuru 'to dig/scoop up'[14][15][16]) the latent life force present in the soil or the female womb.[17][18]

Extent of cult

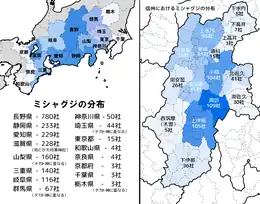

Research conducted by local historian Imai Nogiku in the 1950s revealed a total of 780 shrines to the Mishaguji (or similarly-named deities) within Nagano Prefecture, 109 of which are in the Suwa area (comprising the modern municipalities of Chino, Suwa, Okaya, Shimosuwa, Fujimi, and Hara).[19][20]

As noted above, worship of possibly related kami with names such as 'S(h)aguji' or 'S(h)agoji' are also attested in neighboring areas, being notably widespread throughout the Kantō and Chūbu regions of Japan. Shrines enshrining these gods are found in places such as Shizuoka (233 shrines), Aichi (229 shrines), Yamanashi (160 shrines), Mie (140 shrines) and Gifu (116 shrines).[21][22] On the other hand, such shrines are conspicuously absent in the two prefectures of Niigata and Toyama, located to the north of Nagano.[21]

The head shrine of the local Mishaguji shrine network in Suwa is the Ontō Mishaguji Sōsha (御頭御社宮司総社) in Chino, situated within the grounds of the Moriya family estate. Before the Meiji period, the Moriya (守矢氏) served in the Upper Suwa Shrine as priests known as Kan-no-Osa (神長) or Jinchōkan (神長官). The Jinchōkan was second only to the Ōhōri (大祝), the shrine's high priest revered both as the descendant and the living vessel or shintai of the shrine's deity, Takeminakata, and was responsible for conducting the shrine's religious ceremonies. Summoning and dismissing the Mishaguji in rituals was held to be the prerogative of this priest.[23][24] However, local historians believe that the Maemiya (前宮), one of the Upper Shrine's two sub-shrines and one of the four sites that comprise the Suwa Grand Shrine complex, was the original center of local Mishaguji worship, known as the 'Great Mishaguji' (大御社宮神 Ō-Mishaguji).[25] Medieval records refer to the "twenty Mishaguji of the Maemiya" (前宮廿ノ御社宮神).[26]

Function

Mishaguji are believed to be spirits that dwell in rocks, trees, or bamboo leaves,[4][27][28] as well as various man-made objects such as phallic stone rods (石棒 sekibō),[29][30][31] grinding slabs (石皿 ishizara) or mortars (石臼 ishiusu).[32][20] In addition to the above, Mishaguji are also thought to descend upon straw effigies[33] as well as possess human beings, especially during religious rituals.[32][28]

This concept of Mishaguji as a possessing spirit are reflected in texts that describe Mishaguji being 'brought down' (降申 oroshi-mōsu, i.e. being summoned into a repository, whether human or object) or 'lifted up' (上申 age-mōsu, i.e. being dismissed from its vessel) by the Moriya jinchōkan, the priest with the exclusive right to call upon Mishaguji in the religious rites of the Suwa Grand Shrine.[34]

Folk beliefs considered Mishaguji to be associated with fertility and the harvest,[20] as well as healers of diseases like the common cold or pertussis.[35][36] Mishaguji have been worshipped as tutelary deities of whole villages (産土神 ubusuna-gami) as well as specific kinship groups (祝神 iwai-gami).[37] Further reflecting this relationship between Mishaguji and local communities is their being believed to preside over the act of founding villages[36] as well as their being associated with the broadly similar concept of saikami (patrons of boundaries or borders).[38]

Mishaguji in Suwa

Within the Suwa region, syncretism with other myths has resulted in the representation of Mishaguji as snakes, as well as their connection with the story of Takeminakata-no-kami and Moreya-no-kami; Moreya-no-kami is said to represent the autochthonous worship of Mishaguji that syncretized with the worship of new gods represented by Takeminakata-no-kami.[39]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Imai, Nogiku (2017). "Mishaguji no tōsa shūsei (御社宮司の踏査集成)". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. pp. 212–281.

- ↑ Yamamoto, Kenichi (2010). "Mishakuji: taiko kara no seimei no tsuranari (ミシャクジ-太古からの生命のつらなり)". Collected Papers on Japanese Culture at Teikyō University (帝京日本文化論集) (17): 255–271.

- ↑ Oh, Amana ChungHae (2011). Cosmogonical Worldview of Jomon Pottery. Sankeisha. pp. 156–159. ISBN 978-4-88361-924-5.

- 1 2 Moriya, Sanae (1991). Moriya Jinchōke no ohanashi (守矢神長家のお話し). In Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum (Ed.). Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori (神長官守矢資料館のしおり) (Rev. ed.). p. 4.

- ↑ Ōwa, Iwao (1990). Shinano Kodai Shikō (信濃古代史考). Tokyo: Meicho Shuppan. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-4626013637.

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). p. 189.

- 1 2 Miyasaka (1987). p. 24.

- ↑ Hosoda, Kisuke (2003). Kenpō Moriya bunsho o yomu: chūsei no shijitsu to rekishi ga mieru (県宝守矢文書を読む―中世の史実と歴史が見える). Hoozuki Shoseki. pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Yanagita, Kunio (1910). Ishigami mondō (石神問答). Tokyo: Juseidō (聚精堂). pp. 2ff.

- ↑ Yamada, Hajime (1929). Suwa Daimyōjin (諏訪大明神). Shinano Kyōdo Sōsho (信濃郷土叢書), vol. 1. Shinano Kyōdo Bunka Fukyūkai (信濃郷土文化普及協会). pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Miwa, Iwane (1978). Suwa Taisha (諏訪大社). Gakuseisha. p. 31.

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). pp. 189-191.

- ↑ Imai, Nogiku (2017). "Misakujin (御作神)". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. pp. 181–189.

- ↑ "'sakuru' (さく・る)". goo Jisho (goo辞書).

- ↑ "'sakuru', 'shakuru' (さく・る、しゃく・る)". Weblio Jisho (Weblio辞書).

- ↑ Tanaka, Atsuko (2011). "古社叢の「聖地」の構造(3)─諏訪大社の場合 (The Sacred Site Structure of Ancient Shrine Groves (3) Primitive Beliefs in Suwa)" (PDF). Journal of Kyoto Seika University: 130.

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). pp. 192-194.

- ↑ Oh (2011). p. 178.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Oh (2011). p. 164.

- 1 2 Ōwa (1990). p. 199.

- ↑ Tanaka (2011). p. 128.

- ↑ Moriya (1991). pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Miyasaka. (1987). pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Kitamura, Minao (2017). ""Mishaguji saiseitai"-kō (「ミシャグジ祭政体」考)". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. p. 105.

- ↑ Kitamura, Minao (2017). ""Mishaguji saiseitai"-kō (「ミシャグジ祭政体」考)". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 27.

- 1 2 Tanigawa (1987). p. 185, 193.

- ↑ Louis-Frédéric (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Translated by Roth, Käthe. Harvard University Press. p. 838. ISBN 978-0674017535.

- ↑ Ouwehand, Cornells (1964). Namazu-e and Their Themes: An Interpretative Approach to Some Aspects of Japanese Folk Religion. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 197.

- ↑ "Sekibō worship in the Jōmon Period (縄文時代の石棒祭祀 Jōmon-jidai no sekibō-saishi)". Suwa City Museum (諏訪市博物館).

- 1 2 Ōwa (1990). p. 191.

- ↑ Tanigawa (1987). pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 26.

- ↑ Fukuta, Ajio; et al., eds. (1999). 日本民俗大辞典〈上〉あ〜そ (Nihon Minzoku Daijiten, vol. 1: A - So). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. p. 802. ISBN 978-4642013321.

- 1 2 Miyasaka (1987). p. 25.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 23.

- ↑ Gotō, Sōichirō, ed. (1996). 'Tōno Monogatari' kenkyu sōkō (『遠野物語』研究草稿). Meiji University School of Political Science and Economics. p. 20.

- ↑ 『東洋神名事典』p. 463

Bibliography

- Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum, ed. (1991). 神長官守矢資料館のしおり (Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori) (in Japanese) (Rev. ed.). Chino.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Oh, Amana ChungHae (2011). Cosmogonical Worldview of Jomon Pottery. Sankeisha. ISBN 978-4-88361-924-5.

- Ōwa, Iwao (1990). 信濃古代史考 (Shinano Kodai Shikō) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Meicho Shuppan. ISBN 978-4626013637.

- Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). 諏訪市史 上巻 原始・古代・中世 (Suwa-shi Shi (History of Suwa City), vol. 1: Genshi, Kodai, Chūsei) (in Japanese). Suwa.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tanigawa, Kenichi, ed. (1987). 日本の神々―神社と聖地〈9〉美濃・飛騨・信濃 (Nihon no kamigami: Jinja to seichi, vol. 9: Mino, Hida, Shinano) (in Japanese). Hakusuisha. ISBN 978-4-560-02509-3.

- Ueda, Masaaki; Gorai, Shigeru; Miyasaka, Yūshō; Ōbayashi, Taryō; Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1987). 御柱祭と諏訪大社 (Onbashira-sai to Suwa-taisha) (in Japanese). Nagano: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 978-4-480-84181-0.

- Yanagita, Kunio (1910). 石神問答 (Ishigami mondō) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Juseidō (聚精堂). pp. 2ff.

.svg.png.webp)