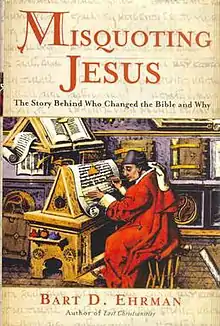

First edition | |

| Author | Bart D. Ehrman |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Textual criticism |

| Publisher | HarperCollins |

Publication date | 2005 |

| Pages | 256 |

| ISBN | 978-0-06-073817-4 |

| OCLC | 59011567 |

| 225.4/86 22 | |

| LC Class | BS2325 .E45 2005 |

| Preceded by | Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine (2004) |

| Followed by | The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed (2006) |

Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (published as Whose Word Is It? in the United Kingdom) is a book by Bart D. Ehrman, a New Testament scholar at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.[1] Published in 2005 by HarperCollins, the book introduces lay readers to the field of textual criticism of the Bible. Ehrman discusses a number of textual variants that resulted from intentional or accidental manuscript changes during the scriptorium era. The book made it to The New York Times Best Seller List.[2]

Summary

Ehrman recounts his personal experiences with the study of the Bible and textual criticism. He summarizes the history of textual criticism, from the works of Desiderius Erasmus to the present. The book describes an early Christian environment in which the books that would later compose the New Testament were copied by hand, mostly by Christian amateurs. Ehrman concludes that various early scribes altered the New Testament texts in order to de-emphasize the role of women in the early church, to unify and harmonize the different portrayals of Jesus in the four gospels, and to oppose certain heresies (such as Adoptionism).

Ehrman discusses the significance in understanding how Christianity stemmed from Judaism. Christianity was foreshadowed by Judaism, and was seen as the first "religion of the book" in Western civilization.[3] Judaism, in its earliest years, was distinctive in some ways to other religions; it was the most-recognized monotheistic faith, set apart from all the other faiths that were polytheistic. The most significant and unique aspect of Judaism, Ehrman points out, was of having instructions along with ancestral traditions written down in sacred books, which were found in no other religious faith on the face of the earth during the given time period. The sacred books read by the Jews stressed ancestral traditions, customs, and laws. In order to pinpoint the canonization of the religion of Christianity, Ehrman discusses how the New Testament came into existence during the first century of the common era. Jews were scattered throughout the Roman Empire, and only relied upon the writings given to Moses by God, the Torah, which literally means "law" or "guidance". Ehrman continues on discussing how those writings were canonized and then later on recognized as the "Old Testament" following the rise of Christianity at the given time period.

In order to summarize his point that Christianity at its beginning was a religion of the book, Ehrman concludes how Jesus himself was a rabbi and adhered to all the sacred books held by the Jews, especially the Torah.[4]

Reviews and reception

Alex Beam of The Boston Globe wrote that the book was "a series of dramatic revelations for the ignorant", and that "Ehrman notes that there have been a lot of changes to the Bible in the past 2,000 years. I don't want to come between Mr. Ehrman and his payday, but this point has been made much more eloquently by... others."[5]

Jeffrey Weiss of The Dallas Morning News wrote, "Whichever side you sit on regarding Biblical inerrancy, this is a rewarding read."[6] The American Library Association wrote, "To assess how ignorant or theologically manipulative scribes may have changed the biblical text, modern scholars have developed procedures for comparing diverging texts. And in language accessible to nonspecialists, Ehrman explains these procedures and their results. He further explains why textual criticism has frequently sparked intense controversy, especially among scripture-alone Protestants."[7]

Charles Seymour of the Wayland Baptist University in Plainview, Texas, wrote, "Ehrman convincingly argues that even some generally received passages are late additions, which is particularly interesting in the case of those verses with import for doctrinal issues such as women's ordination or the Atonement."[8]

Neely Tucker of The Washington Post wrote that the book is "an exploration into how the 27 books of the New Testament came to be cobbled together, a history rich with ecclesiastical politics, incompetent scribes and the difficulties of rendering oral traditions into a written text."[9]

Craig Blomberg, of Denver Seminary in Colorado, wrote on the Denver Journal that "Most of Misquoting Jesus is actually a very readable, accurate distillation of many of the most important facts about the nature and history of textual criticism, presented in a lively and interesting narrative that will keep scholarly and lay interest alike."[10] Blomberg also wrote that Ehrman "has rejected his evangelicalism and whether he is writing on the history of the transmission of the biblical text, focusing on all the changes that scribes made over the centuries, or on the so-called 'lost gospels' and 'lost Christianities,' trying to rehabilitate our appreciation for Gnosticism, it is clear that he has an axe to grind."[10]

In 2007, Timothy Paul Jones wrote a book-length response to Misquoting Jesus, called Misquoting Truth: A Guide to the Fallacies of Bart Ehrman's "Misquoting Jesus". It was published by InterVarsity Press. Novum Testamentum suggested that Misquoting Truth was a useful example of how conservative readers have engaged Ehrman's arguments.[11]

In 2008 evangelical biblical scholar Craig A. Evans wrote a book called Fabricating Jesus: How Modern Scholars Distort the Gospels: despite having been written in response to Ehrman's book, Fabricating Jesus includes a lengthy critique of several scholars of the historical Jesus, including the Jesus Seminar, Robert Eisenman, Morton Smith, James Tabor, Michael Baigent and Elaine Pagels and Ehrman himself. In his work, Evans accused the mentioned scholars of creating absurd and unhistorical images of Jesus, while also arguing against the historical value of New Testament apocrypha.[12]

Another book written in response to Ehrman was Can We Still Believe the Bible? An Evangelical Engagement with Contemporary Questions, published in 2014 by evangelical biblical scholar Craig Blomberg. The book contains a lengthy response to Misquoting Jesus, pointing out that nothing in Ehrman's work is new to biblical scholars – both liberal and conservative – and that the interpolations he mentions are all explicitly mentioned as such in standard Bibles and that, in any case, no cardinal doctrine of Christianity is jeopardized by these variants.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Interview with Bart Ehrman, Publishers Weekly, January 25, 2006.

- ↑ Publisher's website. HarperCollins.com.

- ↑ pp. 19–20

- ↑ p. 20

- ↑ Beam, Alex (Apr 12, 2006). "Book review: The new profits of Christianity". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2009-04-06. (behind paywall)

- ↑ Weiss, Jeffrey (Apr 16, 2006). "Book review: Some ask: Are Bible texts authentic? Are stories true?". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story behind Who Changed the..." Booklist. Nov 15, 2005. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story behind Who Changed the..." Library Journal. 2005. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Tucker, Neely (March 5, 2006). "The Book of Bart". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- 1 2 "Book review: Misquoting Jesus". Denver Seminary. March 5, 2006. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Book Notes". Novum Testamentum. 50: 417. 2008.

- ↑ Evans, Craig A. (2008). Fabricating Jesus: How Modern Scholars Distort the Gospels. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0830833559.

- ↑ Blomberg, Craig L. (2014). Can We Still Believe the Bible?: An Evangelical Engagement with Contemporary Questions (in German). Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1441245649.

External links

- Misquoting Jesus Internet Archive

- Misquoting Jesus Archived 2015-06-19 at the Wayback Machine from bartdehrman.com

- Misquoting Jesus excerpts from NPR

- Stanford lecture on "Misquoting Jesus"