The Missouri River Valley outlines the journey of the Missouri River from its headwaters where the Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin Rivers flow together in Montana to its confluence with the Mississippi River in the State of Missouri. At 2,300 miles (3,700 km) long the valley drains one-sixth of the United States,[1] and is the longest river valley on the North American continent.[2][3] The valley in the Missouri River basin includes river bottoms and floodplains.

Geography

The Missouri's valley ranges from 6 miles (9.7 km) to 10 miles (16.1 km) wide from edge to edge, with gentle slopes from the adjacent upland to the valley floor. Other segments are narrow, less than two miles (3 km) wide, with rugged valley sides. Generally, the wide segments trend west–east and the narrow segments trend north–south.[4]

Starting in the state of Montana, the Missouri River Valley travels through North Dakota, South Dakota, forms the shared border of eastern Nebraska and western Iowa, goes into Kansas and then eastward through the state of Missouri. The valley travels through several distinct ecoregions with distinct climate, geology and native species.[5]

The Loess Hills are a unique geographic feature of the valley. Loess, a wind-deposited soil, is compounded in slowly rising hills at various points in extreme eastern portions of Nebraska and Kansas along the Missouri River Valley, particularly near the Nebraska cities of Brownville, Rulo, Plattsmouth, Fort Calhoun, and Ponca, rising no more than 200 feet (61 m) above the Missouri River bottoms. The majority of these hills stretch along the east side of the river, from Westfield, Iowa in the north to Mound City, Missouri in the south.

Flooding

Channeling and levee construction have altered how floods affect the Missouri River Valley. Several large floods have affected the valley since Europeans first came into the area. The first recorded event is the Great Flood of 1844, which crested in Kansas City on July 16, 1844, discharged 625,000 cubic feet (17,698 m3) per second. The Great Flood of 1951 discharged 573,000 cubic feet (16,226 m3) per second, cresting on July 14, 1951. This flood devastated the lower Missouri River Valley, including Kansas City, along a reach of river where there was no levee system. The Kansas City Stockyards were destroyed and the city was forced to move the development of an airport away from the Missouri River bottoms. The Great Flood of 1993 discharged at 541,000 cubic feet (15,319 m3) per second and devastated much of the upper valley.[6]

Culture

The Missouri River Valley Culture, or "Steamboat Society," was first defined in the 1850s by non-Indian residents of the Dakotas who sold wood to steamboats or trapped furs along the river bottoms. Gambling, prostitution and illegal alcohol sales to American Indians fueled the growth of the culture, which eventually included outfitters, livestock ranchers and tribal agents. A line of urbanized centers grew along the river in response which bloomed when reservations were allotted throughout the region.[7]

Uniting themselves along the banks of the river, South Dakotans identify themselves even today as "East River" or "West River". According to the University of South Dakota, the associated present-day culture of the Missouri River Valley contains a broad swath of political, social, historic, and artistic perspectives.[8]

Management

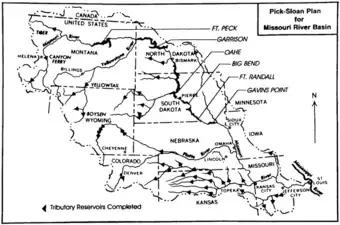

The Flood Control Act of 1944 introduced the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program. Designed to benefit the entirety of the Missouri River Basin including the valley, the plan sought to meet the needs of residents throughout the area by providing irrigation systems and reservoirs for storing water where needed, along with hydroelectric power, flood control measures, and navigational improvement.

The government did not complete the comprehensive plan for the valley, instead introducing individual projects, including the construction of six dams. They are the Fort Peck Dam in Montana, the Garrison Dam in North Dakota, the Oahe, Big Bend, and Fort Randall Dams in South Dakota, and the Gavins Point Dam in Nebraska and South Dakota. The channel of the Missouri was also improved extensively along with the development of ports such as the one in Omaha throughout the 1950s and 60s for greater volumes of traffic on the river, which have never come to fruition.[9]

Protected areas

Following at a distance of years the first recorded exploration of the majority of the valley by the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806), there have been numerous attempts at preserving the natural habitats of the Missouri River Valley, spurred in its early days by concerns of duck hunters, for the Missouri basin lies across a major migration route, the Central Flyway, and in the river's lower reaches, the Mississippi Flyway. Today there are several protected areas throughout the course of the Missouri River Valley. They include the Theodore Roosevelt National Park, Mark Twain National Forest in Missouri and the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge in Nebraska. The Katy Trail travels along the valley in Missouri. Other protected areas in the valley include:

See also

- Tributaries of the Missouri River (category)

- Ionia Volcano

- Little Dixie (Missouri)

- River basins in the United States

References

- ↑ Beatte, B. and Dufur, B. (2007) The Katy Trail Nature Guide and River Valley Companion. Katy Trail. Retrieved 2/5/08.

- ↑ The Missouri River Story - USGS Archived 2006-09-23 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2/5/08.

- ↑ "The Missouri River", Prairie Fire. Retrieved 2/5/08.

- ↑ Bluemle, J.P."The Missouri River", North Dakota Geological Survey. Retrieved 2/5/08.

- ↑ "The Missouri River Valley" Archived 2008-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 2/5/08.

- ↑ Larson, Lee W. "The Great USA Flood of 1993". National Weather Service.

- ↑ Sisson, R., Zacher, C.K., et al. (2007) The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. p 47.

- ↑ "Missouri River Institute", University of South Dakota. Retrieved 2/5/08.

- ↑ "United States Geography", MSN Encarta. Retrieved 2/5/08. Archived 2009-11-01.