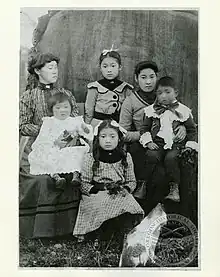

Miyo Iwakoshi was one of the first Japanese settlers in Oregon. She travelled to the state in 1880. She became known as the "Western Empress" among Japanese settlers due to her willingness to help Japanese Immigrants travel and reside in Oregon.[1]

_with_brother%252C_Riki%252C_and_adopted_dauther%252C_Tama_Jewel_Nitobe%252C_Portland%252C_OR%252C_ca._1886.jpg.webp)

Early life

Evidence is limited on Miyo's youth but she appears to have come from a financially stable household within Northern Japan.[1] She adopted Tama Jewel Nitobe, at the age of 5, prior to her departure from Japan.[2] Tama's biological parents are noted as "unknown" on her birth certificate.[1] Whilst in Japan in 1879, Iwakoshi, age 27, met an Australian-Scottish professor who went by the name Captain Andrew McKinnon, age 53.[3] During this period, the Meiji Restoration of 1868 involved the Japanese government industrializing its agriculture, incentivizing foreigners, like Mr. McKinnon, to travel there and implement new techniques and expertise on their farming industry.[1] At the time, Andrew was in Northern Japan teaching animal husbandry but hoped to travel to America.[1] One year later they set sail for the Oregon Coast.[3]

Arrival to Oregon

Miyo arrived in Oregon in 1880 by ship via the Columbia River and setting anchor in Portland, alongside her husband Andrew McKinnon, her daughter Tama Nitobe and her younger brother, Rikichi.[4][5] After the selling of their ship, they migrated towards Gresham, Oregon.[2][5] They settled down in East Multnomah County just on the outskirts of Gresham.[6] Captain McKinnon built The Orient Mill and named it after his wife.[7][8] To build the Mill they did receive some assistance from a friend, Captain Robert Smith.[3] The Orient sawmill helped Iwakoshi and her family survive and later on served as the name of the surrounding community Orient that formed.[1] 5 years after their start in Oregon, Miyo's husband, Andrew McKinnon died leaving the family to fend for themselves.[1]

Japanese community

Initially, as the first female Japanese Issei in Oregon, it was challenging having no other women of the same nationality.[2] Many Japanese people at this time faced exclusionary policies and mindsets from the U.S. Government.[1] Anti-Japanese sentiment really shifted into focus near the end of 1910 as WWI was fast approaching.[7] A Japanese-exclusion movement formed within different communities due to competition in the agriculture world and hatred that formed as WWI began to commence.[7] However, with time more Japanese Nikkei came to the farming regions of Gresham and dispersed throughout the area.[9] With the agricultural decline and social unrest in Japan due to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, a large population of Japanese Issei immigrated to the United States in hopes for employment and new opportunities.[10][5] During this period, Miyo earned the title of Western Empress as she willingly provided resources, contracts and advice to the incoming Japanese immigrants in the area.[1]

Other ventures

In the spring of 1911, Miyo imported silkworm cocoons from Japan to try and raise them to see if they would survive the Oregon environment.[11] By June, She had a successful silkworm colony that produced hundreds of yards of fine pure white silk thread.[12][13] The silk produced was equal in quality to silk made in other countries and she hoped to highlight the possibility of a larger scale silk production in Oregon.[13]

Legacy

In 1891, Miyo's daughter, Tama Nitobe, at 16 years of age married Japanese restaurant business owner Shintaro Takaki, becoming the first Oregon Japanese immigrant family and they had 6 children.[3][10] By 1973, 3 of Miyo's grandchildren were deceased; a grandson and granddaughter were shot and one grandson died by a car accident.[1]

Burial

Miyo Iwakoshi passed away in 1931 at the age of 79 years old. She was provided with no headstone or clear marker as to where she was buried. During the period of time in which she died, Anti-Japanese sentiment indicated that she might have been laid to rest outside of the Pioneer Cemetery.[14] There were 3 different cemeteries within Gresham; Escobar, Gresham Pioneer and White Birch cemetery. Pioneer Cemetery, the oldest of the 3 cemeteries, has 2 acres of land whereas the other two locations have approximately half an acre of land each.[15] A Anti-Japanese sentiment group within Gresham, the Japanese Exclusion League, desired for any Japanese people to be buried in White Birch cemetery rather than Pioneer Cemetery.[15] For years without an obvious burial marker it was assumed that she was buried in one of the other cemeteries or surely outside of Pioneer Cemetery. After further research, it was later on discovered that she was buried close to her husband, in Pioneer Cemetery, with a Japanese Cedar marking her grave.[1][14] In 1988, the Japanese-American community and the Gresham Historical Society contributed a granite headstone and a planted Japanese Maple as an honorable marker of her burial.[14] Years later the trees planted in honor of her still grow to immeasurable heights.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Spencer, Quinn (February 17, 2021). "Miyo Iwakoshi: the first Japanese immigrant to Oregon". Metro. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- 1 2 3 D., Chandler, J. (2013). Hidden history of Portland, Oregon. History Press. ISBN 978-1-62619-198-3. OCLC 858901608.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Yasui, Barbara (1975). "The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834–1940". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 76 (3): 225–257.

- ↑ Peggy Nagae (2012). "Asian Women: Immigration and Citizenship in Oregon". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 113 (3): 334. doi:10.5403/oregonhistq.113.3.0334. S2CID 164850887.

- 1 2 3 Pursinger, Marvin Gavin (1961). Oregon's Japanese in World War II : a history of compulsory relocation. OCLC 3545940.

- ↑ Tamai, Lily Anne Welty; Nakashima, Cindy; Williams, Duncan Ryuken (2017). "Mixed Race Asian American Identity on Display". Amerasia Journal. 43 (2): 176–191. doi:10.17953/aj.43.2.176-191. ISSN 0044-7471. S2CID 149613393.

- 1 2 3 Azuma, Eiichiro (1993). "A History of Oregon's Issei". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 94 (4): 315–367.

- ↑ E., Powell, Linda (1990). Asian Americans in Oregon : a portrait of diversity and challenge. Oregon State University Extension Service and Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station. OCLC 890653262.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "9 Locating Nihonmachi: Urban Erasure, Memory, and Visibility in Japantown, USA", Communicative Cities in the 21st Century, Peter Lang, 2013, doi:10.3726/978-1-4539-1084-9/23, ISBN 9781433122590, retrieved February 24, 2023

- 1 2 Inada, Lawson; Azuma, Eiichiro; Kikumura, Akemi; Worthington, Mary (1993). In this great land of freedom : the Japanese pioneers of Oregon (1 ed.). 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, California: In this great land of freedom : the Japanese pioneers of Oregon. ISBN 9781881161011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ "Estacada progress. (Estacada, Or.) 1908–1916, August 03, 1911, Image 2 « Historic Oregon Newspapers". oregonnews.uoregon.edu. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Beaver State Herald". oregonnews.uoregon.edu. June 23, 1911. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- 1 2 "Mosier Bulletin". oregonnews.uoregon.edu. July 18, 1911. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Keizur, Christopher. "Collection celebrates Gresham’s Japanese-American citizens". TheOutlookOnline.com. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Bergen, Teresa; Davis, Heide (2021). Historic cemeteries of Portland, Oregon. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 9781467148610.