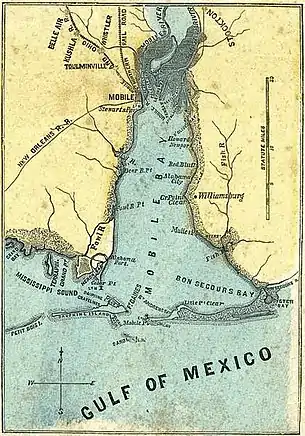

Mobile, Alabama during the American Civil War was an important port city on the Gulf of Mexico for the Confederate States of America. Mobile fell to the Union Army late in the war following successful attacks on the defenses of Mobile Bay by the Union Navy.

Early war years

Mobile had grown substantially in the period leading up to the Civil War when the Confederates heavily fortified it. The 1860 U.S. Census reported that Mobile had 29,258 residents, making it the 27th largest city in the country. When the Confederacy was formed after the secession of eleven Southern slave-holding states, Mobile became the 4th largest city in the breakaway nation. Statistically, Mobile in 1860 was 69 percent whites, 3 percent free blacks and 28 percent slaves.[1]

One observer described the city in 1861, "With a population of thirty thousand the city contains many pleasant residences, embowered in shade trees, and surrounded by generous grounds. It is rendered attractive by its tall pines, live oak, and Pride-of-China trees."[2]

Military activities

As war erupted, military fervor in Mobile was high, and hundreds of able-bodied men responded to recruitment drives and signed up for service in the Confederate army. In addition, several antebellum militia companies formally volunteered their services and enrolled. The Creole Guard and the Southern Guard were among those new troops that manned Mobile's defenses, as did the Mobile Cadets (Co A of the 21st Alabama became part of the 3rd Alabama Infantry, while Co K, Mobile Cadets, remained with the 21st Alabama).[3] The Pelham Cadets (1st Battalion Alabama Cadets) served at Mobile and in various parts of Alabama in 1864 and 1865.[4]

With secession and the creation of the Confederate States Navy came the need for warships. Mobile's shipmakers responded by hastily constructing a series of vessels for naval usage, among them the CSS Gaines and the CSS Morgan, both partially armored wooden ships with 2-inch armor plating over unseasoned wood.[5]

Early in the war, Union naval forces established a blockade under the command of Admiral David Farragut. The Confederates countered the blockade by constructing "blockade runners;" fast, shallow-draft, low-slung ships that could either outrun or evade the blockaders, maintaining a trickle of trade in and out of Mobile.

The CSS Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy vessel in combat, was built and tested in Mobile before being shipped to Charleston, South Carolina. Hunley was ready for a demonstration by July 1863. Supervised by Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan, The innovative boat successfully attacked a coal flatboat in Mobile Bay, suggesting that the relatively new concept of submarine warfare might be viable.[6]

Mobile was the site of several Civil War hospitals for wounded and ill soldiers. Mobile City Hospital treated a significant number of civilians who became sick during the war from yellow fever and other diseases. The Marine Hospital cared for Confederate soldiers, and later in the war, for Union troops as well.[7]

The civilian front

Food and others shortages were common in Mobile as the blockade tightened and cut the city off from external sources of raw materials, cloth, and other sundries. In April 1863, a riot erupted as angry citizens demanded bread to feed their families. The outbreak was short-lived, but lingering discontent and anger simmered through the spring and summer, finally boiling over in September. More than 100 frustrated women gathered on Spring Hill Road, some carrying banners that read "Bread or Blood" on one side and "Bread and Peace" on the other. Several had brought brooms and even a few axes as weapons. They stormed up Dauphin Street, demanding satisfaction for their bread shortage. A local militia force was mobilized with orders to stop the mob, but they refused to march out of sympathy with the women's cause. The rioters reached the office of Mayor R. H. Slough and demanded relief from the food shortage. When Slough promised to get them food, the mob broke up and the ladies returned to their homes.[3]

The fall of Mobile

In August 1864, Union Navy Admiral David Farragut's warships fought their way past the two forts (Gaines and Morgan) guarding the mouth of Mobile Bay and defeated a small force of Confederate gunboats and one ironclad, the CSS Tennessee, in the Battle of Mobile Bay. It is here that Farragut is alleged to have uttered his famous "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" quote. The Union action did not force the surrender of the city of Mobile, but it did effectively close off the city's access to Mobile Bay and eliminate the residual traffic of the local blockade runners.[8]

On April 12, 1865, three days after the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Courthouse, the city of Mobile surrendered to the Union army to avoid destruction following the Union victories at the Battle of Spanish Fort and the Battle of Fort Blakely.[9]

Ironically, on May 25, 1865, the city suffered loss when some three hundred people died as a result of an explosion at a federal ammunition depot on Beauregard Street. The explosion left a 30-foot (9 m) deep hole at the depot's location, sank ships docked on the Mobile River, and the resulting fires destroyed the northern portion of the city.[10]

Notable leaders from Mobile

Among the more notable Civil War personalities from Mobile were Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes (an antebellum attorney in Mobile following his U.S. Navy service) and Brig. Gen. Zachariah C. Deas (a Mobile merchant and cotton broker whose brigade fought at the Battle of Chickamauga, where they routed the Union division of Philip H. Sheridan and killed Brig. Gen. William H. Lytle).[11]

Mobile resident Augusta Jane Evans was a staunch states' rights activist who became a leading pro-Confederacy propagandist during the war. The novelist nursed sick and wounded Confederate soldiers at Fort Morgan on Mobile Bay. She also sowed sandbanks for the defense of the community, wrote patriotic addresses, and set up a hospital, Camp Beulah, near her residence. Augusta's propaganda masterpiece was Macaria, a novel that promoted national desire for an independent national culture and reflected Southern values as they were at that time.[12]

Robert H. Slough served as the mayor of Mobile throughout most of the Civil War, serving from 1862 until the war's end in 1865. His tenure was wrapped by that of former U.S. Minister to Mexico and Alabama state legislator John Forsyth Jr., who preceded Slough in 1861 and then succeeded him in 1865.[13]

Dr. Josiah C. Nott of Mobile was a leading researcher into the causes of yellow fever. During the war, he was a surgeon and staff officer in the Confederate Army, and in charge of inspecting the military hospitals in Mobile. Two of his sons died in the war while serving in Alabama regiments.[14]

See also

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Bergeron Jr., Arthur, Confederate Mobile, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8071-2573-3

- Delaney, Caldwell. The Story of Mobile, Mobile, Alabama: Gill Press, 1953. ISBN 0-940882-14-0

- Thomason, Michael. Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7

- National Park Service: Teaching with Historic Places: Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay

- Flotte's Notes on Mobile, Alabama, History

Notes

- ↑ U.S. Census of 1860.

- ↑ Bergeron, p. 3.

- 1 2 "Flotte's Notes". Archived from the original on 2008-01-05. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ The War For Southern Independence in Alabama

- ↑ Friend, Jack, West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1-59114-292-8

- ↑ "Friends of the Hunley". Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ Historic Markers of the City of Mobile

- ↑ NPS: Fort Morgan and Mobile Bay

- ↑ Thomason, p. 113.

- ↑ Delaney, pp. 144-46.

- ↑ NIE

- ↑

- Riepina, Anne Sophia, Fire and Fiction: Augusta Jane Evans in Context, 2000.

- ↑ Political Graveyard

- ↑ Alabama Healthcare Hall of Fame Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

External links

Further reading

- Amos, Harriet Elizabeth. "All-Absorbing Topics: Food and Clothing in Confederate Mobile." Atlanta Historical Society Journal No. 22 (Fall-Winter, 1978)

- Amos, Harriet Elizabeth. "City Belles: Images and Realities of Lives of White Women in Antebellum Mobile," Alabama Review Vol. 34, No. 1 (January 1981)

- Amos, Harriet Elizabeth. Cotton City: Urban Development in Antebellum Mobile. University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

- Amos, Harriet Elizabeth. "Social Life in an Antebellum Cotton Port: Mobile, Alabama 1820-1860." Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 1979.