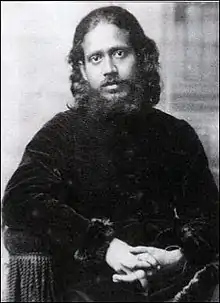

Mohini Mohun Chatterji (1858 - 1936) was a Bengali attorney and scholar who belonged to a prominent family that for several generations had mediated between Hindu religious traditions and Christianity.[1] He joined the Theosophical Society in 1882 and became Assistant Secretary of the Bengal branch. Later that year, he claimed he became a "chela" in probation of the Mahātmā Koot Hoomi, and saw apparitions of Mahatmas on five or six occasions.[2] According to Theosophists, he eventually failed as a chela, and resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1887, after only five years of membership.

Early life and education

Mr. Chatterji, usually known as Mohini, was born in 1858 into a Brahmin family. His mother, Chandrajyoti Devi, was the granddaughter of Hindu reformer Rammohan Roy.[3][4] He attended university in Calcutta, and was awarded Bachelor of Laws and Master of Arts degrees. His wife was the niece of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.[5]

Theosophical Society involvement

Mohini was an active member of the Brahmo Samaj,[3] and became a member of the Bengal Theosophical Society on April 6, 1882, the same day the Bengali branch was established. In the same month, he had his first meeting with Madame Blavatsky when she visited the Calcutta Theosophists.[3] According to Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett, "When HSO opened the first Theosophical Sunday School in Calcutta on March 10, 1883, with 17 boys, Mohini was appointed their teacher".[6]

Being a chela of Master K.H., he gave evidence to the Society for Psychical Research concerning the reality of psychic phenomena at Adyar,[7] in what came to be known as the Hodgson investigation.

Mohini worked as private secretary to H. S. Olcott and accompanied him and Madame Blavatsky on their European tour in 1884:

The purpose of his trip to Europe was seemingly to give the members there some assistance in understanding the Eastern doctrines which had been brought into prominence by APS in his book Esoteric Buddhism."[8]

From a letter from Mme. Blavatsky to Mr. Sinnett, it would appear that he was going to be used in a similar manner as Babaji was:

On February 17th Olcott will probably sail for England on various business, and Mahatma K. H. sends his chela, under the guise of Mohini Mohun Chatterjee, to explain to the London Theosophists of the Secret Section — every or nearly every mooted point and to defend you and your assumptions. You better show Mohini all the Master's letters of a non-private character — saith the Lord, my Boss — so that by knowing all the subjects upon which he wrote to you he might defend your position the more effectually — which you yourself cannot do, not being a regular chela. Do not make the mistake, my dear boss, of taking the Mohini you knew for the Mohini who will come. There is more than one Maya in this world of which neither you nor your friends and critic Maitland is cognisant. The ambassador will be invested with an inner as well as with an outer clothing. Dixit.[9]

Mohini was present in London in 1884 when the young German artist Hermann Schmiechen painted the Portraits of the Masters. He was described by Laura Carter Holloway as being “nearer the Master than all others in the room, not even excepting H.P.B.”[10]

In 1885, he went to Ireland to lecture, and helped to establish the Dublin Lodge of the TS. There, he produced a deep impression on Irish poets George Russell (Æ) and William Butler Yeats and is said to have influenced the oriental turn of their writings. Yeats wrote a poem entitled 'Mohini Chatterjee'.

The adulation he received from some of the European members fueled his pride and he showed poor judgment on several matters. In late 1885, Mohini became involved in scandal with female Theosophists. The case came to public attention when one of the women, in response to Blavatsky's criticisms, intended to publicize letters written to her by Mohini Chatterjee.[11] Mme. Blavatsky wrote to Mr. Sinnett in March 1886:

Mohini was sent, and at first won the hearts and poured new life into the L.L. He was spoiled by male and female adulation, by incessant flattery and his own weakness.[12]

Mohini resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1887 and went back to his former home in Calcutta, where he resumed his practice of law.

Writings

Mohini wrote poetry and prose in both English and his native Bengali.

He and Mrs. Holloway wrote Man: Fragments of Forgotten History, published in 1887 under the pseudonym "Two Chelâs".[13]

He translated The Crest-Jewel of Wisdom (Viveka-Cūḍāmaṇi) of Sankaracharya. He worked with G. R. S. Mead in translating the Upanishads in 1896, using the pseudonym J. C. Chattopadhyaya.[14]

Later years

Yeats and George Russell (Æ) believed that at the turn of the century Mohini was working as a lawyer in Bombay. According to Harbans Rai Bachchan, the last heard of him was that he was a blind old man living in London with his daughter, in the early 1930s.[15] Mohini died in February, 1936.

Online resources

Articles

- Mohini Mohun Chatterji at Theosopedia.

- Morality and Pantheism by Mohini Chatterji

- A Few Words on The Theosophical Organization by Mohini Mohun Chatterji and Arthur Gebhard

- On the Higher Aspects of Theosophic Studies by Mohini M. Chatterji

- Qualifications for Chelaship by Mohini M. Chatterjee

- On the Existence of the Mahatmas by Mohini M. Chatterji

- The Crest Jewel of Wisdom translated by Mohini M Chatterji

- Atmanatma-Viveka: Discrimination of Spirit and Not-Spirit translated by Mohini M Chatterji

- Mukhopadhyay, Mriganka (2020). "Mohini: A Case Study of a Transnational Spiritual Space in the History of the Thesosophical Society". Numen. 67 (2–3): 165–190. doi:10.1163/15685276-12341572.

Additional resources

See also references in:

Notes

- ↑ Diane Sasson, Yearning for the New Age (Bloomington, IN:Indiana University Press, 2012), 78.

- ↑ A Casebook of Encounters with the Theosophical Mahatmas Case 29, compiled and edited by Daniel H. Caldwell

- 1 2 3 Mukhopadhyay, Mriganka (2020). "Mohini: A Case Study of a Transnational Spiritual Space in the History of the Thesosophical Society". Numen. 67 (2–3): 165–190. doi:10.1163/15685276-12341572. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ↑ George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

- ↑ ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

- ↑ George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

- ↑ ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

- ↑ George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

- ↑ A. Trevor Barker, The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett Letter No. XXVIII, (Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1973), ??.

- ↑ Laura C. Holloway, “The Mahatmas and Their Instruments Part II,” The Word (New York), July 1912, pp. 200-206, available at The Blavatsky Archives Portraits of the Mahatmas

- ↑ See The Open University web site

- ↑ Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 14o (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 459.

- ↑ The complete text is available at

- ↑ ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

- ↑ See The Open University web site