| Total population | |

|---|---|

| cca. 1,000–2,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Molise region, Italy | |

| Languages | |

| Slavomolisano, Italian | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Croats, Italians |

| Part of a series on |

| Croats |

|---|

|

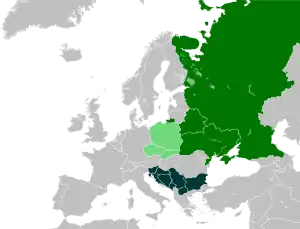

Molise Croats (Croatian: Moliški Hrvati) or Molise Slavs (Italian: Slavo-molisani, Slavi del Molise) are a Croat community in the Molise province of Campobasso of Italy, which constitutes the majority in the three villages of Acquaviva Collecroce (Kruč), San Felice del Molise (Filić) and Montemitro (Mundimitar).[2] There are about 1,000 active and 2,000 passive speakers of the Slavomolisano dialect. The community originated from Dalmatian refugees fleeing from the Ottoman conquests in the late 15th and 16th centuries.[2][3]

Identity and status

The community does not have an ethnonym of their own, but are traditionally accustomed to the term Zlava and Škjavuna ("Slavs").[4] Since 1999, the governments of Italy and Croatia recognize the community as a Croatian minority in Italy.[5] However, the people consider themselves to be Italo-Slavs or Croatian-speaking Italians, and the term "Molise Croat" is a recent exonym rather than their own name for themselves,[6] dating to the middle 19th century.[7] Historical terms for this community include Schiavoni, Sklavuni, Skiavuni and Šćavuni ("Slavs"), and also demonymic de Sclavonia, de Dalmatia or partibus Illirie.[8] In 1967 the minority has also been called "Serbo-Croats of Molise" (Serbo-croati del Molise[9]).

The communities did not use a specific ethnonym, rather tribal determinants naša krv (our blood), naša čeljad (our dwellers), braća naša (our brothers), while for language speaking na našo (on our way).[7] Another important aspect of identity is the tradition according which the community vaguely settled "z one ban(d)e mora" (from the other side of the sea).[10] In 1904, Josip Smodlaka recorded a testimony su z' Dalmacije pur naši stari (from Dalmatia are our ancestors).[11]

History

The Adriatic Sea since the Early Middle Ages connected the Croatian and Italian coast.[12] The historical sources from 10-11th centuries mention Slavic incursions in Calabria, and Gargano peninsula.[12] Gerhard Rohlfs in dialects from Gargano found many old Croatian lexical remains, and two toponyms Peschici (*pěskъ-) and Lesina (*lěsь, forest), which indicate Chakavian dialect.[13] In the 12th century are confirmed toponyms Castelluccio degli Schiavoni and San Vito degli Schiavoni.[12] Between tt 13th and 15th centuries, toponyms Slavi cum casalibus (Otranto, 1290), Castellucium de Slavis (Capitanata, 1305), casale Sclavorum (Lavorno, 1306), clerici de Schalvis (Trivento, 1328), S. Martini in Sclavis (Marsia, 13th century), S. Nikolò degli Schiavoni (Vasto, 1362).[14] In 1487 the residents of Ancona differed the Slavi, previously settled, and the newcomers Morlacchi.[11] In the 16th century, Abraham Ortelius in his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570), West of Gargano in today's province of Molise mentioned Dalmatia,[15] and on Gargano also exist cape Porto Croatico and cove Valle Croatica.[16]

According to evidence, Molise Croats arrived in the early 16th century.[17] The documents from the episcopal archive of Termoli indicate that Molise Croats arrived 1518 in Stifilić (San Felice).[18] A stone inscription on the church in Palata, destroyed in the 1930s, read Hoc Primum Dalmatiae Gentis Incoluere Castrum Ac Fundamentis Erexere Templum Anno 1531 (Residents of Dalmatia first settled the town and founded the church in 1531).[17] The mention of Croatian Ban Ivan Karlović (d. 1531) and absence of any Turkish word in folk poetry additionally proves this dating,[17][19] and unity of elements in Croatian folk poetry from diverse regions at the end of 15th and 16th century.[20]

Serafino Razzi in his work Cronica Vastese (1576–1577) wrote that the Slavs who came across the sea founded in Molise region settlements San Felice, Montemitro, Acquaviva Collecroce, Palata, Tavenna, Ripalta, San Giacomo degli Schiavoni, Montelongo, San Biase, Petacciato, Cerritello, Sant'Angelo and Montenero di Bisaccia.[7][14] Other Slavs settled in Vasto, Forcabobolani, San Silvestro, Vacri, Casacanditella, Francavilla al Mare, and in Abruzzo among others.[14] For the Slavic congregation in Rome was established Illyrian brotherhood of St. Jerome, which was confirmed by Pope Nicholas V in 1452.[14] Slavs founded fifteen settlements in Molise,[21] according to Giacomo Scotti with around seven or eight thousand people,[22] of which only three (San Felice, Montemitro, Acquaviva Collecroce) today have a Slavic-speaking community.[11]

The existence of this Slavic colony was first mentioned in the 1850s, and was unknown outside Italy until 1855 when linguist Medo Pucić from Dubrovnik journeyed to Italy and overheard a tailor in Naples speaking with his wife in a language very similar to Pucić's own.[23] The tailor then told him that he came from the village of Živavoda Kruč, then part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.[23]

Origin

The geographical origin of the Molise Croats (Slavs) has been vastly theorized. Vikentij Makušev while researching Slavic immigrants in Naples and Palermo, heard "Old-Slavonic" words rab, teg, kut, dom, gredem etc., and being uninformed about their common use in Chakavian speech of Dalmatia, thought that they were Bulgarians.[14][24] Risto Kovačić,[25][26] Miroslav Pantić,[26] Giovanni de Rubertis and Graziadio Isaia Ascoli,[27] considered Molise Croats to be Serbs from Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbian littoral.[26][28] Josip Gelecich considered the area of Dubrovnik-Bay of Kotor.[26][24] There's almost no historical and linguistical evidence that Molise Croats originated from continental Balkans or Montenegro.[26][29]

A more specific and generally accepted area of origin is considered to have been Dalmatia. As such, Josip Aranza considered Zadar region,[30][26][24] R. T. Badurina southern Istria,[26][29] Mate Hraste the hinterland of Zadar and Šibenik,[31] while Walter Breu the Neretva valley.[32] According to linguistic features, it has been established that the area of origin was Zabiokovlje and Makarska Riviera (Josip Smodlaka, Josip Barač, Milan Rešetar, Žarko Muljačić, Dalibor Brozović, Petar Šimunović).[33][26][29]

Language

The language of Molise Croats is considered to be important because of its archaism, preserved old folk songs and tradition.[34][35] The basic vocabulary was done by Milan Rešetar (in monography), Agostina Piccoli (along Antonio Sammartino, Snježana Marčec and Mira Menac-Mihalić) in Rječnik moliškohrvatskoga govora Mundimitra (Dizionario dell' idioma croato-molisano di Montemitro), and Dizionario croato molisano di Acquaviva Collecroce, the grammar Gramatika moliškohrvatskoga jezika (Grammatica della lingua croato-molisana), as well work Jezik i porijeklo stanovnika slavenskih naseobina u pokrajini Molise by Anita Sujoldžić, Božidar Finka, Petar Šimunović and Pavao Rudan.[36][37]

The language of Molise Croats belongs to Western Shtokavian dialect of Ikavian accent,[15] with many features and lexemes of Chakavian dialect.[15][29] The lexicon comparison points to the similarity with language of Sumartin on Brač, Sućuraj on Hvar, and Račišće on Korčula,[36][29] settlements founded almost in the same time as those in Molise,[36] and together point to the similarity of several settlements in South-Western and Western Istria (see Southwestern Istrian dialect), formed by the population of Makarska hinterland and Western Herzegovina.[36][37]

Giacomo Scotti noted that the ethnic identity and language was only preserved in San Felice, Montemitro and Acquaviva Collecroce thanks to the geographical and transport distance of the villages from the sea.[38] Josip Smodlaka noted that during his visit in the early 1900s the residents of Palata still knew to speak in Croatian about basic terms like home and field works, but if the conversation touched more complex concepts they had to use Italian.[39]

Antroponyms

The personal names, surnames and toponyms additionally confirm the origin of Molise Croats.[16] Preserved Italianized surnames in Acquaviva Collecroce include Jaccusso (Jakaš), Lali (Lalić), Matijacci (Matijačić), Mileti (Miletić), Mirco (Mirko), Papiccio (Papić), Pecca (Pekić, Peršić), Radi (Radić), Tomizzi (Tomičić), Veta (Iveta);[36] in San Felice include Blasetta (Blažeta), Gliosca (Joško), Petrella (Petrela), Radata (Radetić), Zara (Zaro, Zadro);[36] in Montemitro include Blascetta (Blažeta), Giorgetta (Jureta), Lali, Miletti, Mirco, Staniscia (Stanišić), Gorgolizza (Gurgurica, Grgurić), Sciscia (Šišić), Juricci (Jurić), Joviccio (Jović) etc.[36][40]

The surnames differ; patronymics with suffix -ović (Marovicchio, Marcovicchio, Pastrovicchio), diminutive-hypocoristic (Vucenichio, Popicchio, Milicchio), nicknames attribute (Vecera, Tosti, Poganizza, Bilac, Berhizz), ethnic-toponyms attribute (Klissa, Lisa, Zara, Rauzei, Schiavone di Corzula, Traù, Ciuppana, de Raguza), Italian lexic origin (Curic, Scaramucchio).[41]

A rich array of kinship names (including vlah, fiancé, and vlahinja, fiancée), and many lexemes indicate that among the population of Molise Croats were genuine Vlach communities.[42] It has been preserved the tradition of nickname Mrlakin (Morlak; "shepherd") and old homeland for the Mirco family (Baćina lakes near Ploče in Dalmatia).[43] On the Vlach influence point forms Mrlakina, Jakovina, Jureta, Radeta, Peronja, Mileta, Vučeta, Pavluša, patronyms with suffix -ica (Vučica, Grgorica, Radonjica, Budinica), name suffix -ul (Radul, Micul), and verb čičarati / kikarati.[44]

Toponyms

There's an abundant number of toponyms which include the ethnonyms Sciavo, Schiavone, Slavo, Sclavone and their variations in South-Eastern Italy.[45] The evidence shows that Italians usually used this ethnonyms as synonyms for the name of Croats and residents of Dalmatia.[45][46] For example, in 1584 in Palcarino degli Schiavoni (Irinia) was mentioned a priest de nazione Schiavone o Dalmatico.[47]

The names of Molise settlements are Italianized Acquaviva Collecroce (Živavoda Krȕč), Montemitro (Mundìmītar), San Felice (Stifìlīć > Fìlīć).[48] Toponymy includes several semantic categories; characteristics of the ground (Brdo, Dolaz, Draga, Grba, Kraji, Livade, Polizza, Ravnizza, Vrisi), soil composition (Stina, Drvar), hydronyms (Vrila, Jesera, Jaz, Locqua, Potocco, Coritti, Fontizza), flora (Dubrava, Valle di Miscignavizza, Paprato, Topolizza), fauna (Berdo do kujne, Most do tovari), position of the object (Monte svrhu Roccile, Fonte donio, Fonte zdolu Grade), human activity (Gradina, Ulizza, Puč, Cimiter, Selo, Grad, Stasa), and property owners (Maseria Mirco, Colle di Jure).[49] The toponymy of Molise is almost identical to the toponymy of Makarska Riviera.[50]

Culture

The community is adherent to Catholicism.[51]

Upon settling in inhabited current area, Molise Croats engaged in subsistence agriculture (mostly producing grain, as well as some vine-cultivation and other kinds of agriculture) and animal husbandry, as well as home lacemaking and the trade of resulting goods.[18] In modern times, olive and olive oil production are also cultivated. The village residents mostly work in nearby towns, like Termoli and San Salvo.[46]

The long-term exposure to the disintegration processes and Italian foreign language surroundings, as well absence of cultural institutions, resulted in the loss of ethnic identity.[52] The ethnic identity of Molise Croats consists of a common language, shared ancestry and physical appearance, personal names and toponyms, common customs (living and dressing), as well an oral tradition of migration.[38] In 1904, Slavenska knjižnica (Biblioteca Slava) was founded in Acquaviva Collecroc; from 1968, the journal Naš jezik was released, and again between 1986–1988 as Naš život in Slavomolisano dialect.[53][54] From 2002, a journal entitled Riča živa has been released.[54] Local amateur associations preserve the tradition, folklore, and language.[54] In 1999, the Agostina Piccoli Foundation was founded, which in 2002 was officially recognized by Italy as an institution for preservation and protection of Molise Croats culture and tradition.[55]

Population

In the late 18th century, Giuseppe Maria Galanti in his work Descrizione dello stato antico ed attuale del Contado di Molise (1781), as Schiavoni settlements considered Acquaviva Collecroce (1380 pop.), Montemitro (460), San Siase (960), San Felice (1009), Tavenna (1325), and noted that the residents of Ripalta (781) spoke equally poorly Slavic and Italian.[46]

Giovenale Vegezzi Ruscalla in his work Le Colonie Serbo–Dalmate del circondario di Lacino - provincia di Molise (1864), recorded that only three villages preserved la lingua della Dalmazia, and population was, like previously by Galanti, around 4,000 people.[46] For the residents of Tavenna noted that until 1805 they still spoke slavo-dalmato, but in the last census (probably from 1861), certain sixty elders who preserved the language did not declare for lingua dalmata because was afraid of being considered strangers.[22]

In 1867, Graziadio Isaia Ascoli considered that around 20,000 residents of Molise region were of Slavic origin.[22] This figure is considered to be unfounded.[22]

During the years, due to economic and social issues, many families migrated to Northern Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and overseas to United States, Brazil, Argentina, Canada, and Western Australia.[46][56][2] The population figures reported in the census do not necessarily show accurate data for the language speakers.[1]

| Population number according census[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census year | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1936 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | |

| Acquaviva Collecroce | 1777 | 1820 | 1937 | 2212 | 2243 | 2017 | 2058 | 2172 | 2250 | 1808 | 1157 | 1017 | 897 | |

| Montemitro | 799 | 787 | 849 | 1006 | 1017 | 944 | 935 | 915 | 906 | 874 | 749 | 624 | 544 | |

| San Felice | 1460 | 1436 | 1550 | 1664 | 1681 | 1655 | 1592 | 1653 | 1727 | 1371 | 1003 | 911 | 881 | |

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 Piccoli 1993, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 Šimunović 2012, p. 189.

- ↑ Colin H. Williams (1991). Linguistic Minorities, Society, and Territory. Multilingual Matters. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-85359-131-0.

Croatian in three villages in the Molise region stems from settlement there by Slavs during the later Middle Ages (Ucchino, 1957).

- ↑ Bernd Kortmann; Johan van der Auwera (27 July 2011). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 435–. ISBN 978-3-11-022026-1.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 91.

- ↑ Anita Sujoldžić, "Molise Croatian Idiom", Coll. Antropol. 28 Suppl. 1 (2004) 263–274

Along with the institutional support provided by the Italian government and Croatian institutions based on bilateral agreements between the two states, the Slavic communities also received a new label for their language and a new ethnic identity – Croatian, and there have been increasing tendencies to standardize the spoken idiom on the basis of Standard Croatian. It should be stressed, however, that although they regarded their different language as a source of prestige and self-appreciation, these communities have always considered themselves to be Italians who in addition have Slavic origins and at best accept to be called Italo-Slavi, while the term "Molise Croatian" emerged recently as a general term in scientific and popular literature to describe the Croatian-speaking population living in the Molise.

- 1 2 3 Perinić 2006, p. 92.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 91–106.

- ↑ Atti del Convegno internazionale sul tema: gli Atlanti linguistici, problemi e risultati: Roma, 20-24 ottobre 1967. Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. 1969.

I tre villaggi serbo-croati del Molise sono invece completamente isolati, quindi risentono molto dell'ambiente circostante.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 203.

- 1 2 3 Perinić 2006, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Šimunović 2012, p. 190.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 190, 198.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Šimunović 2012, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 Šimunović 2012, p. 193.

- 1 2 Šimunović 2012, p. 195.

- 1 2 3 Telišman 1987, p. 187.

- 1 2 Telišman 1987, p. 188.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 94, 99–100.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 198.

- ↑ Ivan Ninić (1989). Migrations in Balkan history. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 72. ISBN 978-86-7179-006-2.

In Molise alone fifteen Slavic settlements came into existence, but the majority of Slavs in cities and villages were, ...

- 1 2 3 4 Piccoli 1993, p. 177.

- 1 2 Perinić 2006, p. 94–95.

- 1 2 3 Perinić 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Univerzitet u Beogradu. Filološki fakultet (1971). Prilozi za književnost, jezik, istoriju i folklor, Том 37 (in Serbian). p. 37. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

Risto Kovačić visited Molise in 1884 and wrote a report to the Serbian Learned Society about Serbian settlements. In his report, published in 1885, he emphasized that there were nine Serbian settlements of as many as 16,000 people. In three settlements about 4,000 people still spoke Serbian, considered themselves Serbs, and kept tradition of badnjak as their legacy.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Šimunović 2012, p. 192.

- ↑ Kovačić, Risto (1885). "Srpske Naseobine u Južnoj Italiji". Glasnik Srpskoga učenog društva, Volume 62. Serbian Learned Society. pp. 273–340 [281]. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

По господину де Рубертису, вели госп. Асколи ондје, први Срби — или како их онамо обичније зову Schiavoni или Dalmati — дошли су у Молизе заедно с Арбанасима (Албанези) што их је онамо довео Скендербег.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 95–96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Perinić 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ Aranza, Josip (1892). Woher die südslavischen Colonien in Süditalien. Berlin: Archiv für slavische Philologie, XIV. pp. 78–82.

- ↑ Mate Hraste (1964), Govori jugozapadne Istre, Zagreb, p. 33,

Tom se prilikom stanovništo toga plodnog kraja u zaledju Zadra do Šibenika selilo na sve strane. Jedan dio je odselio u Istru, jedan se odselio u pokrajinu Molise; nastanio se u nekoliko sela [...] Mišljenje Badurinino da su hrvati u južnoj Italiji doselili iz štokavskog vlaškog produčja u južnoj Istri ne može stati, jer je prirodnije da su hrvati iz Dalmacije krenuli u Italiju ravno morem preko Jadrana, nego preko Istre u kojoj bi se u tom slučaju morali neko vrijeme zaustaviti

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Walter Breu (1 January 2003). "Bilingualism and linguistic interference in the Slavic-Romance contact area of Molise (Southern Italy)". Words in Time: Diachronic Semantics from Different Points of View. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 352–. ISBN 978-3-11-089997-9.

- ↑ Muljačić, Žarko (1997). "Charles Barone, La parlata croata di Acquaviva Collecroce". Čakavska Rič. XXIV (1–2): 189–190.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 197–198, 202–203.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 99–100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Šimunović 2012, p. 194.

- 1 2 Perinić 2006, p. 97.

- 1 2 Telišman 1987, p. 189.

- ↑ Telišman 1987, p. 190.

- ↑ "Italianizirana hrvatska prezimena" (in Croatian). Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 196.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 193–194, 197.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 194, 197.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 197.

- 1 2 Šimunović 2012, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Piccoli 1993, p. 176.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 199–200.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 200.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 200–202.

- ↑ Šimunović 2012, p. 202.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 98–99.

- ↑ Telišman 1987, p. 188–189.

- ↑ Telišman 1987, p. 189–190.

- 1 2 3 Perinić 2006, p. 102.

- ↑ Perinić 2006, p. 102–103.

- ↑ Kukvica, Vesna (2005). "Migracije Moliških Hrvata u Zapadnu Australiju". In Lovrenčić, Željka (ed.). Iseljenički horizonti, Prikazi i feljtoni [Migrations of Molise Croats in Western Australia] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Hrvatska matica iseljenika. ISBN 953-6525-37-2.

Sources

- Heršak, Emil (1982), "Hrvati u talijanskoj pokrajini Molise", Teme o iseljeništvu. br. 11, Zagreb: Centar za istraživanje migracija, 1982, 49 str. lit 16.

- Telišman, Tihomir (1987). "Neke odrednice etničkog identiteta Moliških Hrvata u južnoj Italiji" [Some determinants of ethnic identity of Molise Croats in Southern Italy]. Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian). Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies. 3 (2).

- Piccoli, Agostina (1993). "20 000 Molisini di origine Slava (Prilog boljem poznavanju moliških Hrvata)" [20,000 Molise residents of Slav origin (Appendix for better knowledge of the Molise Croats)]. Studia ethnologica Croatica (in Croatian). Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. 5 (1).

- Perinić, Ana (2006). "Moliški Hrvati: Rekonstrukcija kreiranja ireprezentacijejednog etničkog identiteta" [Molise Croats: Reconstruction of creation and representation of an ethnic identity]. Etnološka Tribina (in Croatian). Croatian Ethnological Society and Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. 36 (29).

- Šimunović, Petar (May 2012). "Moliški Hrvati i njihova imena: Molize i druga naselja u južnoj Italiji u motrištu tamošnjih hrvatskih onomastičkih podataka" [Molise Croats and their names: Molise and other settlements in southern Italy in the standpoint of the local Croatian onomastic data]. Folia onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (20): 189–205. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

External links

- "Acquaviva Collecroce".

- Gabriele Romagnoli. "Mundimitar" (in Italian and Croatian).

- Euromosaic. "Le croate en Italie" (in French). Research Centre of Multilingualism.

- Francesco Martino (March 2006). "Alla scoperta degli ultimi 'schiavuni'" (in Italian). balcanicaucaso.