| Mona and Monito Islands | |

|---|---|

| Reserva Natural Islas de Mona y Monito | |

Higo chumbo (Harrisia portoricensis) in Mona Island. | |

| |

| Location | Puerto Rico |

| Nearest city | Mayagüez, Puerto Rico |

| Coordinates | 18°5′12″N 67°53′22″W / 18.08667°N 67.88944°W |

| Area | 40,045 cuerdas (38,893 acres) |

| Established | 1986 |

| Governing body | Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA) |

| Designated | 1975 |

Mona and Monito Islands Nature Reserve (Spanish: Reserva Natural Islas Mona y Monito) consists of two islands, Mona and Monito, in the Mona Passage off western Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. Mona and Monito Islands Nature Reserve encompasses both land and marine area, and with an area of 38,893 acres[1] it is the largest protected natural area in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (El Yunque National Forest, with 28,434 acres,[2] is the largest in the main island of Puerto Rico). Much like the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean, the Mona and Monito Islands reserve represents a living laboratory for archaeological, biological, geological, oceanographical and wildlife management research.[3][4][5]

Overview

Mona is the third largest island in the archipelago of Puerto Rico and the largest in the Mona Passage. It has an area of 22 square miles (57 km2) and is located 41 miles (66 km) from the main island of Puerto Rico, and 38 miles (61 km) east of the Dominican Republic. Monito, less than a mile across (147 km2), is smaller and located 3.20 miles (5.15 km) northwest off Mona. Although both islands are uninhabited (only researchers and DRNA personnel live on Mona), both form part of barrio Isla de Mona e Islote Monito of the municipality of Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.

Due to the island's historical and natural significance there has been interest in seeking world heritage status for Mona as a UNESCO World Heritage Site by the Puerto Rican government.[6] The name Mona originates from Amona, the original Taíno name for the island.[3]

History

.JPG.webp)

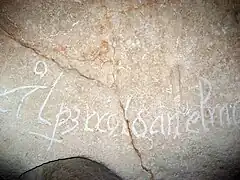

The island of Mona was inhabited by the Taíno people in the Pre-Columbian era[3] and it contains several archaeological and petroglyph sites, most of them in the limestone caves of the island.[7] The caves also contain graffiti from the Spanish colonial and piracy times.[8] Mona, along with Puerto Rico, Vieques and Culebra, were ceded to United States from Spain in 1898 under the Treaty of Paris.[9] On December 22, 1919, the island was declared an "Insular Forest of Puerto Rico", under the auspices of the U.S. Forest Law No. 22. The Mona Island Lighthouse, dating from 1900, was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as Faro de la Isla de la Mona in 1981, and the whole island was added to the NRHP in 1993.[10] Guano mining was the primary industry of Mona for most of its history. The ruins and remnants of the guano mining infrastructure can still be seen today.[11]

Mona and Monito Islands were first designated a U.S. National Natural Landmark in 1975 due to the islands' unusual limestone sea caves and natural history. The site of the National Natural Landmark site includes 14,037 acres out of the 38,893 total acres in the nature reserve.[12] The island of Mona and its surrounding waters were designated a critical habitat in 1977 and 1982 for the yellow-shouldered blackbird (Agelaius xanthomus), the Mona Island boa (Chilabothrus monensis) and the Mona ground iguana (Cyclura stejnegeri). It was designated a nature reserve in 1986, and BirdLife International and the Puerto Rican Ornithological Society recognized it as an Important Bird Area in 2004.[13]

Ecology

.jpg.webp)

Mona and Monito are home to a number of unique animal and plant species found nowhere else in the world.[14] This reserve represents one of the last remaining large tracts of Puerto Rican dry forest along with the Guánica State Forest and the Caja de Muertos Nature Reserve.[15] This type of biome is considered critically endangered.[16]

Flora

Mona is home to the largest population of the rare and Critically Endangered[17] Puerto Rico applecactus or higo chumbo (Harrisia portoricensis). This species of cactus is only found on the islands of the Mona Passage (59,000 individuals in Mona, 148 in Monito and 9 in Desecheo),[17] although it has been recently introduced to the island of Caja de Muertos off southern Puerto Rico by the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources as part of a conservation project due to that island's geographical and ecological similarities with Mona and Monito.[18] This cactus is locally known as higo chumbo, meaning "weighed-down prickly pear", due to the leaning cactus arms caused by the weight of their fruit.[19]

Fauna

The Mona ground iguana (Cyclura stejnegeri)[20] is the largest native land animal, not only in Mona but in the whole archipelago of Puerto Rico, 1.22 metres (4 feet 0 inches) in length. It is critically endangered with an estimated population of 1,500 and only found in the island of Mona. Its numbers have greatly decreased due to the presence of invasive species such as cats which predate on the young, and boar which threaten their nesting sites. Although it inhabits the whole island it only nests in a small region in the southwestern coast as it is the only suitable nesting area with loose sand and direct sunlight. They are primarily herbivorous with a diet consisting of leaves, flowers, berries, and fruits from different plant species.[21][22]

Mona represents the largest nesting site for hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Caribbean.[3] Other endemic fauna in the reserve includes yellow-shouldered blackbirds (Agelaius xanthomus), Mona least geckos (Sphaerodactylus monensis), the Mona ameiva (Ameiva alboguttata), the Mona anole (Anolis monensis), the Mona worm snake (Antillotyphlops monensis), the Mona boa (Chilabothrus monensis), and the Mona coqui (Eleutherodactylus monensis).[14]

Monito is home to the Monito gecko (Sphaerodactylus micropithecus) an endemic lizard which was placed in the endangered species list on October 15, 1982, by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[23]

Extinct species

Mona used to be home to the Puerto Rican amazon (Amazona vittata), now only found in small communities in the main island of Puerto Rico,[24] and the Puerto Rican parakeet (Psittacara maugei),[25] an extinct species of parrot that was found in the island until its extinction during the first half of the 20th century.[26]

_-_Puerto_Rico_Parakeet_-_specimen_-_lateral_view.jpeg.webp)

Recreation

Visits are allowed in Mona through previously obtained permits, which allows visitors to camp, hike, fish and hunt invasive species such as boar.[3] The most common form of transportation is by private yacht, though commercial excursions are available from Cabo Rojo for small groups.

Gallery

Sardinera Beach

Sardinera Beach Cliff near Cueva Diamante

Cliff near Cueva Diamante Armored sea robin with brittle star near Mona

Armored sea robin with brittle star near Mona Cueva Diamante

Cueva Diamante Cliffs above Pajaros Beach

Cliffs above Pajaros Beach Limestone cliffs and reefs.

Limestone cliffs and reefs. Colonial Spanish graffiti in Mona

Colonial Spanish graffiti in Mona Taíno petroglyphs in Mona

Taíno petroglyphs in Mona Nesting hawksbill sea turtle in Mona

Nesting hawksbill sea turtle in Mona Monito island from Mona

Monito island from Mona.jpg.webp) Mona ground iguana

Mona ground iguana Mona Island Lighthouse in 1977.

Mona Island Lighthouse in 1977. Monito's cliffs from a dive boat.

Monito's cliffs from a dive boat..jpg.webp) The rare Monito gecko.

The rare Monito gecko.

See also

References

- ↑ "Reserva Natural Islas de Mona y Monito". DRNA. July 9, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. "El Yunque National Forest".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Isla de Mona – Aquí Está Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Isla de Mona to become the Galapagos of the Caribbean". Ciencia Puerto Rico. November 10, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ Estado Libre Associado de Puerto Rico, Officina del Gobernador, Junta de Calidad Ambiental (1973). Las Islas de Mona y Monito: una evaluación de sus recursos naturales e históricos (in English and Spanish). San Juan: IUCN.

- ↑ CyberNews. "Quiere que Isla de Mona sea un patrimonio". www.wapa.tv (in Spanish). Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ Daley, Jason. "Archaeologists Date Pre-Hispanic Puerto Rican Rock Art for the First Time". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ Santos, Mariela (May 17, 2017). "The Ultimate Guide to Isla de Mona, the Galapagos of the Caribbean". Culture Trip. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ United States. War Department. Porto Rico census office (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899. University of Texas. Wáshington : Imprenta del gobierno.

- ↑ "NPGallery Asset Detail". npgallery.nps.gov. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ Frank, Edward F. "History of the Guano Mining History, Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico" (PDF). Journal of Cave and Karst Studies. 60 (2): 121–125.

- ↑ "National Natural Landmarks – National Natural Landmarks (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ Uribe, Claudio. "Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico". Island Conservation. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- 1 2 "La Mona que pocos conocen". Ciencia Puerto Rico (in Spanish). September 4, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service Caribbean Area. "La Importancia de los Bosques en Puerto Rico".

- ↑ Eric Dinerstein, David Olson, et al. (2017). An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm, BioScience, Volume 67, Issue 6, June 2017, Pages 534–545; Supplemental material 2 table S1b.

- 1 2 USFWS. Higo Chumbo Five-year Review. January 2010.

- ↑ "La Reserva Natural Isla Caja de Muertos". DRNA. June 12, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Higo chumbo". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ↑ Powell, Robert (1999), "Herpetology of Navassa Island, West Indies" (PDF), Caribbean Journal of Science, 35 (1–2): 1–13, archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011, retrieved September 9, 2007

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. "Mona Ground Iguana" (PDF).

- ↑ "Restoring Habitat for The Iguanas of Mona Island". Island Conservation. August 1, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Monito gecko". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Taxonomy: Puerto Rican Parrot". Conservation Management Institute. Archived from the original on October 8, 1999. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2020). "Psittacara chloropterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22685695A179413764. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22685695A179413764.en. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ↑ Charles Arthur Woods, Florence Etienne Sergile (2001). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. CRC Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-8493-2001-1.

.jpg.webp)