| Monkland Canal | |

|---|---|

Weir at Old Palacecraig | |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat length | 71 ft 0 in (21.64 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 14 ft 0 in (4.27 m) |

| Locks | 1 descent of four double locks; two other locks (The descent was duplicated for a period by a rope-worked inclined plane) |

| Status | Unnavigable, partly culverted |

| History | |

| Original owner | Monkland Canal Company |

| Principal engineer | James Watt |

| Date of act | 1770 |

| Date of first use | Progressively from 1771 |

| Date closed | 1942 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Calderbank, near Airdrie |

| End point | Townhead Basin, Glasgow (Later connected to the Forth and Clyde Canal by the "cut of junction") |

| Branch(es) | Four short branches |

| Connects to | Forth and Clyde Canal |

Monkland Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Monkland Canal was a 12+1⁄4-mile-long (19.7 km) canal designed to bring coal from the mining areas of Monklands to Glasgow in Scotland. In the course of a long and difficult construction process, it was opened progressively as short sections were completed, from 1771. It reached Gartcraig in 1782, and in 1794 it reached its full originally planned extent, from pits at Calderbank to a basin at Townhead in Glasgow; at first this was in two sections with a 96-foot (29 m) vertical interval between them at Blackhill; coal was unloaded and carted to the lower section and loaded onto a fresh barge. Locks were later constructed linking the two sections, and the canal was also connected to the Forth and Clyde Canal, giving additional business potential.

Maintaining an adequate water supply was a problem, and later an inclined plane was built at Blackhill, in which barges were let down and hauled up, floating in caissons that ran on rails. Originally intended as a water-saving measure to be used in summer only, the inclined plane was found to pass barges more quickly than through the locks and may have been used all the year.

In the second and third decades of the nineteenth century, technical advances in iron smelting coupled with fresh discoveries of abundant iron deposits and coal measures encouraged a massive increase in industrial activity in the Coatbridge area, and the Canal was ideally situated to feed the raw materials and take away the products of the industry.

The development of railways reduced the competitiveness of the canal, and eventually it was abandoned for navigation in 1952, but its culverted remains still supply water to the Forth and Clyde Canal. Much of the route now lies beneath the course of the M8 motorway, but two watered sections remain, and are well stocked with fish.

Route

The eastern end of the final extent of the canal is at Calderbank, south of Woodside Drive, where there were coal pits; the canal was fed there from the North Calder Water. A reservoir was created at Hillend (east of Caldercruix) to sustain the canal in the dry season, and others were made later.

The canal ran close to the north side of the North Calder Water, passing more coal pits (and later ironstone pits) at Faskine and Palacecraig, then turning north there. Palacecraig was later the southern extremity of the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway. The canal passed under the road at Sikeside (now called Sykeside Road, Cairnhill), from where it is nowadays in culvert.

Turning west it passed under what is now Locks Street, Coatdyke; the name refers to the original canal lock; there is a small sign there recording the history. There was a lock[note 1] to the east of the road, and a basin and second lock to the west of it. This location was called Sheepford Locks, and was the eastern extremity of the canal as originally built. A branch canal called Dixon's Cut was later built from the basin southwards to Dixon's Calder Ironworks, south of the present-day Greenend housing area. The canal then continued westward, a little to the south of the Airdrie to Coatbridge main road.

It passed south of the present-day Main Street area of Coatbridge, from where the short Dundyvan Branch ran southwards. It was built to serve coal pits and then extended to serve the Dundyvan Ironworks with a complex of railway trans-shipment sidings at its termination.[1] The main canal then ran fairly straight from the present-day A725 roundabout at the east end of Coatbridge Main Street to the Sunnyside Street roundabout. At this time Coatbridge had not developed at all, and the canal was simply described as "passing under the Edinburgh and Glasgow Road, by a wooden bridge, termed Coat Bridge, two miles [3 km] west of Airdrie."[2]

Another branch diverged northwards here, to the west of Sunnyside Road: called the Gartsherrie, Hornock and Summerlea Branch Canal, it ended at the Gartsherrie Ironworks, just south of the present-day Gartsherrie Road. It was originally planned to serve coal pits, but it was still unfinished in 1830 when the Baird Brothers established their Gartsherrie Ironworks at its termination.[1]

Continuing westward, the main canal originally crossed the Gartsherrie Burn on Cotes Bridge, a low aqueduct 72 feet (22 m) long and 6 feet (1.8 m) high.[3] (Gartsherrie Burn ran north to south between the alignment of the two present-day railways that cross Bank Street; it was culverted when the area was later developed.) The aqueduct collapsed and had to be repaired in 1858.[1]

The canal then ran broadly west between Bank Street and West Canal Street, then turning a little more northerly from Blairhill Street, south of the present King Street, as far as Blair Street. Just east of Blair Bridge the Langloan branch diverged, heading a short distance south on the eastern margin of West End Park (originally called Yeomanry Park) to a basin serving Drumpellier Pit and Langloan Iron Works, founded in 1841, where Langloan Street now joins Bank Street. There was an 80-yard (73 m) tunnel under Bank Street and Buchanan Street.[1]

Onwards from Blair Bridge the canal is open again; the route here arcs northward towards and through the Drumpellier estate, passing north of Drumpellier Home Farm. The estate had a bridge connecting the northern area. The canal then heads west again, with a short northerly spur serving coal pits at Drumpellier, continuing under the present-day railway line, and under the Cuilhill Road bridge. A little to the west was Cuilhill Gullet, where an island in the canal was formed to enable the construction of the terminal of the Drumpeller Railway (the old spelling). The Railway is described below. Still continuing west, but culverted nowadays, the canal was crossed by a swing bridge at Netherhouse Road, and then at Rodgerfield Road, from where the course of the canal is covered by the M8 motorway.

Easterhouse Road and Wardie Road (Bartiebeith) crossed the canal by bridges, followed by Milncroft Road (an eastward extension of the present road) and then Gartcraig Road. This was probably the westernmost point the canal reached at first under James Watt, when the money ran out. When the canal was extended westward, it passed under the main Cumbernauld Road. The Blackhill incline and locks were at the point where the present M80 motorway joins the M8 motorway. The arrangements at Blackhill are described more fully below.

The canal continued on a broadly westerly course, obliterated now by the motorway, terminating in Townhead Basin fronting to Castle Street, at a point where Parson Street and Alexandra Parade would intersect, under the motorway junction.

When the "cut of junction" was formed, a short section of new canal linking the Monkland Canal to the Forth and Clyde branch canal, it was routed north from the basin under Garngad Hill (now Royston Hill).[1] The route then turned west under Castle Street. The grooves worn by the barge towropes can be seen on the iron facing to Castle Street bridge abutment at this point.[4]

A short branch was formed off the cut off junction to serve industrial premises in the area between the present Royston Road and Charles Street. The cut off junction was originally made to the same depth (4 feet; 1.2 m) as the Monkland Canal, but in 1842 it was deepened to accommodate the larger vessels that could use the Forth and Clyde Canal, which could then reach Tennent's chemical works. Opening bridges were provided at Glebe Street and Port Dundas.[1]

Boats

The boats used on the canal were originally flat-bottomed wooden vessels with a low freeboard; they had no living accommodation nor any protection for their crew, and they were horse-drawn. Hutton says that they were habitually known as "scows". Steam vessels with screw propellers were introduced from the 1850s.

A 61-foot (19 m) iron boat was launched in May 1819 and entered service on the Forth and Clyde Canal as a passenger boat. Named the Vulcan, she is famous for being the first iron boat made in Scotland. Although she operated on another canal, she was made at Thomas Wilson's Faskine boatyard, partly because of the proximity of ironworks and ironfounders. She was scrapped in 1873.

In 1986 Monklands District Council had a replica constructed. This can now be seen on the canal within Summerlee Museum of Scottish Industrial Life.[1]

History

Origins

Prior to 1743 coal had been mined in Little Govan, close to Glasgow. When that working ceased, the price of coal in Glasgow rose considerably, doubling by 1760 (from between 1/1 and 1/3 per cart of 7 cwt), to between 2/1 and 2/6. (1 cwt = 112 lb or 51 kg). Available coal was mined in Lanarkshire, but, before proper roads were built, the cost of transport by horse and cart was a significant factor. When the Trades House of Glasgow protested, one member cited another cause: that the coal masters had combined to keep prices high; he asserted that the price ought not to exceed 1/6, including 6d for cartage and tolls.[5]

The inventor and engineer James Watt said later that Monklands was "a country full of level free coals of good quality, in the hands of many proprietors, who sell them at present at 6d per cart of 7 cwt at the pit".[6]

By 1768, the rapid growth of Glasgow had vastly increased the demand for coal, and its price: several bodies expressed concern, and the magistrates of Glasgow took action. The Lord Provost was James Buchanan of Drumpellier, and the rich Monklands coalfield was practically untapped. Canals were being promoted all over the country, and seemed to be the obvious solution here; the magistrates commissioned James Watt to recommend a route.

In November 1769 he reported back, suggesting two possible routes; one was expensive, at more than £20,000, entering the Clyde at Glasgow Green. Its route involved 25 locks, with a summit 266 feet (81 m) above the level of the Clyde. Watt said:

The Great expense of the above canal and the time that would be consumed in passing the locks ... have made me examine how far it is practicable to bring a canal without any locks ... I find that it can be brought to within a little more than a mile [1.6 km] of the town and that a waggon way or good causeway can be made for the remainder of the way. [This route] ends a little south of Jermiston, there appearing to be no possibility of bringing it near Glasgow on that level."[7]

This proposal seems to ignore completely the major problem of the 96 feet (29 m) of vertical interval at Blackhill, an obstacle that was to cause serious problems later.

On 3 January 1770 the cheaper scheme—at £10,000—was laid before a meeting of business people, and following a second meeting on 11 January a subscription list was opened. The Town Council of Glasgow agreed to subscribe £500, with a complicated precondition designed to prevent the coalowners forming a cartel to keep prices high.

The subscription list was swiftly filled, and the necessary Act of Parliament was secured on 12 April 1770.[3]

The Lord Provost was refunded "£65 as half of his charges in going to and coming from London anent obtaining the Act of Parliament ... the other half of such expense being chargeable on the proprietors of the Monkland Canal".[8]

The Act allowed the proprietors to raise £10,000 by issuing shares, and an additional £5,000 if necessary. Water for the canal was to be extracted from Frankfield Loch, Hogganfield Loch, and any other streams or lochs within 3 miles (5 km) of the proposed route which were not already supplying the Forth and Clyde Canal.[9] The requirement in the Act to take water only from a narrow geographical area, and the prohibition on taking water from sources that fed the Forth and Clyde Canal resulted in continuing water shortage problems later.

Construction starts under James Watt

The construction process was very difficult and protracted. It was supervised by Watt, with work beginning on 26 June 1770 at Sheepford, working westward.[9]

Evidently he let contracts directly and seemingly informally, in 110-yard (100 m) sections;[1] he soon found that contractors were incapable of pricing the jobs properly, or even of carrying out the work effectively, and some of them "had to be dissuaded from trying to carry on". There was a significant shortage of workmen capable of the work, and poaching between contractors became a serious problem.[3]

Watt preferred engineering design to managing the works: "Nothing is more contrary to my disposition than bustling and bargaining with mankind:--yet that is the life I now constantly lead. ... I am also in a constant fear that my want of experience may betray me into some scrape, or that I shall be imposed upon by the workmen."[10]

He experienced severe weather and difficult ground, writing in December 1770:

Notwithstanding the desperate weather I am almost constantly at the canal ... I have a hundred men at work just now, finishing a great hill we have wrought at this twelvemonth. The nastiness of our clay grounds is at present inconceivable; the quantities of rain have been beyond measure. Our canal has not stopped, but it is likely to do so, from our having expended the subscription of [£10,000] upon seven miles [11 km] of the navigation, and having about two miles [3 km] yet to make. We have, however, made a canal of four feet water for one of three feet subscribed to, and have also paid most abominably for our land.[11]

It is clear that he made the canal 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, more than originally specified by the proprietors; this followed a visit by the engineer John Smeaton on 28 July 1770. Smeaton "pointed out that the depth of the canal could with advantage be increased to four feet ... without any additional excavation, and the General Meeting of the proprietors three days later agreed to this". Thomson mentions that this has been overlooked by many writers, including Leslie,[12] who erroneously quotes 5 feet (1.5 m).[3] The depth of the canal was 4 feet (1.2 m) according to Groome[13] but Lewis stated 6 feet (1.8 m)[14] with a width of 35 feet (11 m) at the surface, diminishing to 26 feet (7.9 m) at the bottom. The canal was broad, suitable for boats measuring up to 71 by 14 feet (21.6 by 4.3 m).[13]

Partial opening

As sections of the canal were completed, they were naturally put into use. James Watt kept a journal in which he recorded: 1771 November 26: Coals brought by water to Langloan. 1772 June 30: This day Mr Wark brought a boat of coals to Netherhouse. 1772 October 30: At head of canal. The boat loaded by 12 o'clock with 40 carts coal. ... They came to Mr Dougal's wharf by 3 o'clock having been some time stopped by running aground at the reservoir. 1773 May 10: Legat and Stewart had brought a boat of coals upon the Saturday of which some had gone into town.[15]

(Dougal's wharf was at Easterhouse; the reservoir was a temporary one at The Flatters near Drumpellier.[3])

Watt wrote to Dr Small on 24 November 1772, saying: "We have now four and a half miles [7.2 km] actually filled with water and in use."[16]

Stagnation, and the departure of Watt

Jams Watt appears to have severed his connection with the canal from July 1773; at that time there were 7+1⁄4 miles (11.7 km) of canal dug westwards from Sheepford to Gartcraig. Detail of the activity in the next decade and a half are more sketchy. It seems likely that the initial money subscribed had run out without the canal being completed, and the financial climate made it difficult to continue, and that the company terminated Watt's employment.

Not much coal seems to have traversed the part of the canal that was open, so that quite apart from the shortage of capital to continue construction, the company was making an operating loss and was unable to pay its debts. An extraordinary general meeting was called on 3 May 1780, at which those present decided to make a call of 10% on all shareholders. This was a difficult time to ask for money, as the American War of Independence (1775–83) had ruined many of the Glasgow businesses, dependent on the American tobacco business. Moreover, asking for more money to keep a bankrupt business going was inopportune.

At this time a remark was made, facetiously suggesting filling the canal in. Miller tells the tale:

... for many years, the revenue derived was so trifling, compared with the great outlay of capital, that the shareholders almost despaired of its ever proving a profitable investment. It is said that in 1805, when the annual meeting of shareholders took place, presided over by Mr Colt of Gartsherrie, at the conclusion, murmurs of dissatisfaction prevailed among the members at the very cheerless report. Many propositions were made, and, after discussion, abandoned. At last a question was put to the chairman as to what he thought should be done; he replied, "Conscience, lads! the best thing we can dae, is for ilka ane o' us to fill up the sheugh on his ain lands and let it staun."[17]

Miller dates this at 1805, but Thomson is sure this must have been about 1781.[18] Several writers have taken this as a serious proposal, including the engineer James Leslie in a respected journal.[12] Of course filling in the canal would not have retrieved the money expended in digging it.

As a result of the financial crisis, the funds were not forthcoming and it was decided to sell shares by roup (public auction) on 14 August 1781; presumably these were forfeited shares (i.e. not additional shares). The shares taken up were heavily discounted and not all were taken; the final eleven shares were advertised in the Glasgow Journal on 21 March 1782.[3]

Extension westwards

At this time extent of the canal was the 7+1⁄4 miles (11.7 km) already described, and the western end was at Gartcraig.[3] (See below for a discussion of this location.)

The new proprietors met on 15 April 1782 and resolved "to carry the Monkland Canal from its previous termination to a point nearer the city" and to put into effect measures to deal with "such parts of the canal as shall require cleaning so as to give it four feet of depth of water, being the original depth".[3]

The extension to the canal basin at Townhead, seems to have been completed remarkably quickly. It extended from Gartcraig to Blackhill, and separately at the lower level from there to Townhead. On 16 April 1783 a notice of meeting stated that a forthcoming meeting would "consider a plan and estimate for a junction between the upper and lower parts of the canal at Blackhill, and for a road from the present termination at the West End to the River Clyde".[19]

The canal then consisted of two sections, from Sheepford to Townhead, interrupted by the inconvenient connection at Blackhill, where coals were moved between the two sections by use of the incline: this seems to have been no more than a slope surfaced either for road wagons or provided with rails. The coal was transhipped from barge to waggon and from waggon to barge.

Thomson says that there "is no means of ascertaining the nature of the proposed junction at Blackhill. Supplies of water were so meagre that locks were certainly out of the question and in all likelihood they used some modification of Watt's scheme for letting waggons down an incline, the descending waggons pulling up the unloaded waggons".[20]

Cleland, writing later, says, "The communication between these levels was at that time carried on by means of an inclined plane, upon which the coals were let down in boxes, and re-shipped on the lower level."[21]

The original authorising Act had included a causeway (i.e. a hard roadway) from the Townhead Basin to the centre of Glasgow. This detail was not proceeded with.[22]

Andrew Stirling initiates progress

Returning to 1786, the proprietors of the canal realised that the Blackhill discontinuity had now to be overcome; moreover the best coalfields lay a couple of miles east of Sheepford. An extension east involved locks there with a vertical interval of 21 feet (6.4 m). The two groups of locks would vastly increase the requirement for water; this was readily available in the River Calder, but the Monkland Canal Act had forbidden the abstraction of any water that might later be claimed by the Forth and Clyde Canal, and that canal was itself considering an extension which would require the water.

Andrew Stirling and John Stirling had between them 46 out of 101 shares in the company, and "Only the Stirlings (and particularly Andrew Stirling) were alive to the commercial possibilities".[23]

A way forward was explored, and it emerged that both canals could benefit, if the Monkland took the Calder water and also made a connection to the Forth and Clyde near Townhead; that canal had a branch from its main line to this point to serve local factories. This was at the highest level on the Forth and Clyde Canal, and therefore the entire Forth and Clyde Canal would be fed by the Monkland Canal. This arrangement was ratified by the Monkland proprietors at a General Meeting on 8 January 1787.

Nonetheless, the canal's finances were difficult: from 1782 to the end of 1789, the company had a gross income of £853 17s 5d and had expended £29,966 5s 3d: a loss of £28,112 7s 10d, and at the end of that period most of the individual shareholders had sold out, so that Andrew Stirling was the owner (personally or through his company) of over two thirds of the Canal.[3]

In January 1790 the two canals jointly obtained an Act to make the "cut of junction" physically connecting them. The weak finances of the impoverished Monkland company were reflected in that the Forth and Clyde was to build the new feed from the Calder; it was also empowered to take as much water as it required for its own canal, provided that the Monkland Canal received enough water to maintain navigability. The Monkland Company was obliged to keep its canal open as a watercourse, this being a first charge on it; and it was authorised to extend from Sheepford "to the Calder at or near Faskine or Woodhill Mill and to erect sufficient locks to make it navigable". The Act authorised the Monkland company to raise an additional £10,000 of capital.[24]

The new works are undertaken

The extension to the River Calder was to cost £2,857 5s 0d and the locks at Blackhill £3,982. The cut off junction was to be funded by the Forth and Clyde.

The cut off junction was opened on 17 October 1791; at four feet deep it was the same as the Monkland Canal, although the main line of the Forth and Clyde was deeper. The extension to the Calder was completed in 1792 at a cost of £3,618 16s 3d, a 26% overspend.

The Blackhill locks took much longer, being completed in August 1793[25] although Thomson says (1794).[26] There were four double locks, (i.e. two chambers with three pairs of gates,) each double lock having two falls of 12 feet (3.7 m); the total vertical interval was 96 feet (29 metres).

More prosperous times

Now at last the canal had an efficient means of fulfilling its original purpose: conveying coal from the Monkland pits to Glasgow. Talking of East Monkland in 1792, a writer says that "Twenty years ago coal sold so low as 6d. the cart load; but since the Monkland Canal was opened, it sells at 18d. the cart weighing 12 [long] cwt [610 kg]."[27] In other words, coal extracted at Monkland now found a lucrative market in Glasgow.

Meanwhile, the principal users of the canal, the owners or tacksmen,[note 2] necessarily working deposits close to the canal, reduced in number. In 1793 the Statistical Account comments that the canal is unfinished, but adds:

The canal trade is at present as follows:

1st, Coals navigated by Mr. Stirling -- 50,000 carts 2nd, Ditto by Captain Christie -- 30,000 carts ------------ 80,000 carts.

Stirling also brought 3,000 carts of dung and lime in to his agricultural estates.[28]

In subsequent years, Stirling further expanded his activity and by 1802 he was paying 75% of the tonnage dues on the canal.[3] Meanwhile, a redistribution of shares resulted in all the shares in the canal Company being in the hands of the firm of William Stirling & Sons (52) and Andrew Stirling personally (49). Andrew, John and James Stirling had made themselves the sole members of the Committee of Management and John and James—a majority of two votes out of three—increased the canal tolls to the maximum legally allowed. This led to litigation within the family, and also later from William Dixon, who had coal and iron works near the east end of the canal.[3]

Industrial development

The full opening of the canal encouraged a huge increase in coal mining in the area, and the rise of the ironworks around Coatbridge both resulted from the existence of the canal, and encouraged further development of coal and ironstone extraction.

The early coalmining activity was on the Faskine and Palacecraig estates, which were on the eastern extension. In 1820 the city of Glasgow was consuming "half a million tons of coal a year, almost all of it subject to the high tolls on the Monkland Canal".[3][29] In 1828 a rival company claimed that The Monkland Canal had "for many years yielded a dividend of Cent. per Cent ... arising solely on its Tolls on coal".[30]

The iron industry was given a considerable boost when Blackband ironstone was discovered by David Mushet near Coatbridge in 1805 or 1806. The hot blast process of iron ore smelting was invented by James Beaumont Neilson, introduced in 1828. Several large ironworks were established in the Coatbridge area, seven blast furnaces in 1830, rising to 46 by 1840. These developments led to a vast and rapid increase in the industrial development in the Coatbridge area, focused on iron production and iron manufacturing. This led to a huge increase in demand for iron ore and coal from the pits in the area, and the Monkland Canal was able to transport it: coal carried in 1793 had been 50,000 tonnes, rising to a million tonnes by 1850.[1]

In order to better serve the ironworks, four branches were constructed at the upper end of the canal. The branches to Calder Ironworks and Gartsherrie Ironworks were both about a mile (1.6 km) long, while those to Langloan Ironworks and Dundyvan Ironworks were about 1⁄4 mile (400 m) long.[13]

Competition from railways

From 1828, railways started to be built; at first these did not directly compete with the canal, and the canal used the railways, and short tramways, as feeders, encouraging the connection: "the Canal company were not slow to avail themselves of these iron pathways as feeders to their own trade; and accordingly, wherever it has been practicable, they have formed loading basins and wharves, connecting them by offsets with railways in the vicinity. The additional traffic resulting from this source has been very great."[31]

The Garnkirk and Glasgow Railway opened in 1831 and linking with other railways, it was the first railway that directly competed with the canal. Fearing disaster from this competition, "the company reduced their dues to about one-third of the rate which had been charged up till that time".[31] However "although previously to the opening of the Garnkirk and Glasgow Railway ... the passage-boats rarely carried so many as 20,000 passengers in a year, yet, in the face of that great competition, the number of passengers has been gradually increasing, and [in 1845 or 1846] no fewer than 70,000 persons have been carried by the company's boats."[31]

Prosperity and taken over

In 1846, an Act of Parliament authorised the amalgamation of the canal with the Forth and Clyde Canal, with the Forth and Clyde company paying £3,400 per Monkland share. The original shares had a face value of £100, but there had been some subdivision.[13]

In 1846 Lewis reported: "An extensive basin was lately formed at Dundyvan, for the shipment of coal and iron by the canal from the Wishaw and Coltness and the Monkland and Kirkintilloch railways; and boats to Glasgow take goods and passengers twice every day. [...] The revenue of the canal is estimated at £15,000 [...] per annum."[14][31]

Fullarton, publishing in 1846 says that "a very large sum has recently been expended by the company in the formation of new works, [which has included] additional reservoirs in the parish of Shotts, all uniting in the river Calder which flows into the canal at Woodhall, near Holytown, thereby insuring an abundant supply of water at all times".

"There are three branch-canals from the main water-line, viz. one to Calder[note 3] iron-works near Airdrie, about a mile [1.6 km] in length; another to Dundyvan iron-works, extending to about a quarter of a mile [400 m]; and a third to Gartsherrie works, about a mile [1.6 km] long."[31]

By the 1850s and 1860s, the canal was transporting over one million tonnes of coal and iron per year.

An abortive plan to get to the Clyde

The canal had originally been planned to stop short of central Glasgow, to avoid descending to the lower level there; a causeway was authorised, envisaging horse and cart haulage to the city, but it was not built. In 1786 when the completion of the canal was being proposed, the idea was repeated; however it was never carried out.[22]

Although the Townhead basin served much heavy industry in that quarter of Glasgow, progressive improvements to the navigability of the River Clyde meant that 100-tonne (110-short-ton) ships, and by the early years of the nineteenth century 400-tonne (440-short-ton) ships, could reach the Broomielaw quays from the sea. The conveyance of coal, iron ore and machinery from the canal down to the quays resulted in a huge and inconvenient cartage traffic through the city streets; this "added a cost equivalent to ten miles [16 km] carriage on a railway", and of course involved a trans-shipment. The engineer Rennie designed a canal link from the Monkland Canal to the Clyde in 1797, but it involved 160 feet (50 m) vertical interval of lockage and was impossibly expensive; Stevenson prepared a similar scheme later but it too foundered. The Canal Company bought land for a connecting railway for the purpose in 1824, but that scheme also came to nothing.[32]

Decline

Although the trading position was buoyant in the mid-1840s, as railways developed and improved their own services, the canal lost traffic heavily as the years passed. Thomson says that the Blackhill inclined plane was only used for about 37 years (i.e. until about 1831) but this is completely inconsistent with traffic volumes, and Hutton's statement that it worked until 1887 is more convincing.[1] From that time the declining traffic volume did not require the continued use of the inclined plane, and after standing idle for some years it was finally scrapped.

In 1867 the Caledonian Railway purchased the Forth and Clyde Canal in order to get possession of the harbour at Grangemouth, and by this purchase they acquired the Monkland Canal as well. The purchase guaranteed 6¼ per cent per annum on the capital of £1.14 million.

Traffic declined steadily, from 1,530 thousand tonnes in 1863 to 586 thousand tonnes in 1888, 108 thousand tonnes in 1903 and 30 thousand tonnes in 1921.[3]

Abandonment

In August 1942, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway as successors to the Caledonian Railway, applied to the Ministry of War Transport for an order authorising the abandonment of the canal. Navigation rights were removed by an Act of Parliament passed in 1952.[33]

The Sheepford locks were demolished in 1962.[1]

The canal remained the primary water source for the Forth and Clyde Canal, and so some sections are still in water today, notably the eastern section between Woodhall and eastern Coatbridge, and between the west of that town and Cuilhill. The rest of the waterway to Port Dundas was converted into a culvert to maintain the water flow, and much of it now lies beneath the M8 motorway which was constructed along its path in the early 1970s; the motorway was originally called "the Monkland Motorway".[1]

The culvert remains under the jurisdiction of Scottish Canals (as successor to British Waterways) because of its function as a feeder to the Forth and Clyde Canal.

The Scottish Development Agency was formed in 1975, and the canal was the subject of the Monkland Canal Land Renewal Project. The line of the non-motorway section was protected by the District Council from 1978, and there has been some progress with creating a linear park and walkway along its route.[34] The route forms an important part of the Summerlee Heritage Park and Drumpellier Country Park.[35]

Water supply

Throughout its existence, procuring a reliable water supply was a significant issue for the canal. During the first construction phase under James Watt, Airdrie South Burn was used as a source, and "some sort of lade was carried up the burn for 100 yards [90 m]".[3]

When the Drumpellier section of the canal was completed, the section to the east around Muttonhole (at the west end of Coatbridge) was not ready and a temporary reservoir was created with a turf dam at "the Flatters", near Drumpellier Moss.[3]

In the early 1830s, the embankments were raised (to increase the holding capacity) at Hillend reservoir (near Caldercruix) and at the Black Loch (near Limerigg). About 1836 an entirely new reservoir was built at Lily Loch adjoining Hillend.[3]

Between 1846 and 1849 a new reservoir was made at Roughrigg, (south-east of Airdrie), jointly with the Airdrie and Coatbridge Water Company. The Canal was entitled to draw 300,000 imperial gallons (1.4 ML; 360,000 US gal) annually, and the capacity of Hillend, Lily Loch and Black Loch together was about 1,011 million imperial gallons (4.60 GL; 1.214×109 US gal). Nonetheless, in the dry season of 1849 this proved insufficient and the canal was closed for several weeks; this led to the installation of the Blackhill incline.

The canal's interest in the Roughrigg reservoir was bought out by the Water Company in 1874 for £18,000.[3]

Passengers

Cleland says that in 1813, three passage-boats operated: one was between Glasgow and the locks at Sheepford, "and farmed to a Company for four years", implying that the Canal Company contracted out the operation.

A Boat starts from the Basin at the head of the Town [Glasgow], every lawful day, at four o'clock, P.M. (except when impeded by ice,) and arrives at Sheepford at half past six o'clock. Cabin fare, 1s. 6d.; Steerage, 1s.

A Boat starts from Sheepford Locks at half-past seven o'clock in the morning, and arrives at the Townhead Basin at ten o'clock. The Boat, which leaves Glasgow at four o'clock, P.M. ... and arrives at Sheepford, 10 miles [16 km], half-past six, fare 1s.6d.

To perform the passage in the above time, it is necessary for the Passengers to walk about a quarter of a mile [400 m] at Blackhill Locks, where another Boat is provided.

Cleland informs readers that "Sheepford is within one mile [1.6 km] of Airdrie. Although not regularly, the Boats go occasionally to Faskine, about two miles [3 km] further on, and arrive at seven o'clock, P.M."

The number of passengers which went by these boats was 11,470 in 1814, and 12,773 in 1815, bringing a revenue of £556 19s 1d and £648 13s 10d respectively.[21]

This service seems to have continued for some time: in 1837 "upwards of 50,000 passengers were conveyed between Airdrie and Glasgow".[36]

Hutton shows a photograph of a boat moored at McSporran's stable at Easterhouse; he says that it "is believed to be one used for Sunday school outings", and another photograph of a very crowded boat, "Jenny", taking a works outing on a pleasure trip.[1]

Blackhill locks and incline

At first transfer by boxes or wagons on an inclined plane

When the canal was extended from Gartcraig to Townhead, an incline was constructed at Blackhill—nineteenth-century picture postcards refer to the location as "Riddrie"—to enable the transfer of goods between the two levels of the canal.[37]

It is not clear what the mechanical arrangements for this incline were. Leslie, writing much later, says:

An inclined plane for railway wagons at Blackhill connected the two reaches of the canal. The coals were unloaded from the boats in the upper reach into the wagons, run down the inclined plane, and again loaded into boats in the lower reach, which was a tedious operation, and hurtful to the coals.[12]

Leslie's comments are not unimpeachable. The reference to an "inclined plane" in original sources has led him and some modern writers to assume that this was a rope-worked incline with the wagons on rails, but this is not supported by any contemporary document. The limited financial and technical resources available at this time (Watt had long since departed) suggest that this might have been simply a sloping causeway on which boxes of coals were dragged down loaded, and back up empty. Alternatively it may have had rails—not necessarily metal—with single wagons making the transit. Hutton (page 42) refers to rails at this time.[1]

A set of locks

Leslie continues:

About the year 1788, a set of locks was constructed at Blackhill ... The set of locks at Blackhill consists of four double locks 75 by 14 feet [22.9 by 4.3 metres], having each two lifts of 12 feet [3.7 m], the whole height from reach to reach being generally 96 feet [29 m], but varying a few inches according to the supply of water and to the state of the winds.[12]

At the same time there were provided two locks to raise the level at Sheepford.[12]

Leslie's date seems to be premature; Martin states August 1793 for the opening of the Blackhill locks, apparently[note 4] quoting the Glasgow Mercury for 20 August 1793 and the Glasgow Courier for 15 August 1793.[25]

The locks duplicated

Leslie goes on:

In the year 1837 the two uppermost locks were so much out of repair that it became necessary either to rebuild them or to construct two new ones ... It was resolved to proceed immediately with the construction of two new double locks by the side of the old ones.

These were to replace, and not duplicate, the upper locks only. However:

By the time that the new locks were finished, it had become evident, from the great increase in the trade, that either an entire second set of locks must be constructed, or some other means must be devised for passing a greater number of boats than could be accommodated by one set of locks.[12]

The "other means" was some kind of inclined plane in which canal boats could be lowered and raised to accommodate the vertical interval between the two sections of the canal. At that time, systems of this kind had already been installed in the Shropshire Canal in 1788 and 1790, where 5 tonne boats were hauled up inclines dry, on cradles. In 1798 there had been an attempt on the Somerset Coal Canal to use a system in which 20 tonne boats could rise and descend vertically in a float chamber, the boat contained within a timber caisson; this had been unsuccessful. In 1809 a vertical lift had been installed at Tardebigge, Worcestershire, where boats in a wooden caisson were winched up by manpower; it was not successful and was replaced in 1815.[38]

Finally,[note 5] the Morris Canal was built between 1825 and 1831 in spectacularly hilly country from coal mines down to estuarial rivers in New Jersey, US. Its builders installed 23 inclined planes carrying boats of 18 tons payload: the boats were hauled dry on rail-borne carriages. (Other systems were adopted on the canal later).[39]

However, after consideration of the technical alternatives, it was "resolved to rebuild the two old upper locks and to build two new lower ones, so as to give an entire double set, which was done in 1841".[12]

An inclined plane for canal boats

With the lock system duplicated,

the trade was amply accommodated until July 1849, when the supply of water ran short, notwithstanding that storage is provided exceeding 300,000,000 cubic feet [8,500,000 cubic metres] and the canal was shut in consequence for six weeks. It then became evident that some effectual means must be adopted for preventing any such interruption in future.[12]

The storage capacity in reservoirs already exceeded the catchment, so that larger reservoirs were no solution; back-pumping water from the lower reach to the upper at Blackhill was considered too expensive, and Leslie and a colleague recommended the construction of an inclined plane, in which the empty boats would be hauled up "wet"—floating in a caisson on a rail-borne carriage. The dominant traffic was loaded down to Glasgow and empty back up; the intention was to haul the empty boats up the plane, and to let the loaded boats continue to use the locks. The "wet" system was preferred because boats 70 feet (21 m) long were in use; "dry" haulage required the carriage to traverse a brow, over which the carriage and boat descended into the upper reach, and with a long boat this was impractical.[40] (Hauliers were also said to object to supposed damage to their vessels in this system.)

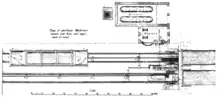

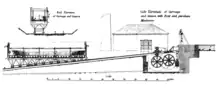

In October 1849 the Committee of Management of the Forth and Clyde Canal (which had by now taken over the Monkland Canal) gave instructions to James Leslie to proceed, and the work was completed by July 1850. The caissons for the boats were made of malleable iron; they were 70 feet long by 13 ft 4 in by 2 ft 9 in high (21.3 by 4.1 by 0.84 metres). The caissons were profiled to conform to the hull of the boats, so as to contain as little excess water as possible, to a depth of 2 feet (0.61 m), and were only to convey empty boats.

The caissons ran on a railway track of 7 ft 0 in (2,130 mm) gauge with 65-pound-per-yard (32 kg/m) flat bottom rails on longitudinal timbers, on a gradient of 1 in 10. There were two tracks. They ran on ten pairs of wheels, of 3 ft (910 mm) diameter except the uppermost pair were 1 ft 6 in (460 mm) and the second pair were 2 ft 3 in (690 mm), to accommodate the wedge shape of the carriage. A continuous rack was fixed to the longitudinal timbers, and a pawl—Leslie calls it a "pall"—attached to the carriage was arranged to engage the rack if the tension was let off the haulage cable.

The caissons were counterbalanced, the ascending caisson and the descending operating together. At the top of the incline, the caisson was brought close to the end of the upper canal reach; it was then forced close to it by hand-operated screw jacks to obtain a water seal, and two guillotine gates, at the end of the caisson and at the end of the canal respectively, were opened. At the bottom, the caisson simply descended into the lower canal reach and became immersed.

There were two 25-horsepower (19 kW) high pressure steam engines. For most of the ascent, the caissons balanced, but as the lower caisson entered the canal water, it gained buoyancy, and the final closing-up required the engines to operate at full power to bring the upper caisson to the canal. The engines operated two shafts carrying the 16-foot-diameter (4.9 m) winding drums, geared to work in opposite directions, so as to achieve the counterbalancing of the caissons. The speed of ascent and descent was about 2 miles per hour (3 km/h), with a passage time of 5 to 6 minutes.

The screw jacks for closing the ascending caisson to the canal gate proved unsatisfactory, requiring the engine operator to make too fine a stop, within 3 inches (76 mm), and a hydraulical accumulator system was later adopted, which could ram the caisson closed over a longer range: up to 3 feet (0.91 m).

When a descent was about to start, the gates were closed and about 50 cubic feet (1,400 L) of water from the space between was lost; it was pumped back to the upper reach.

The practice was to bring up empty boats partly grounded in the caisson, and to adjust the water in the descending caisson (containing water only) for balance.[12]

Shortly after the incline was put to work, one of the gear wheels in the mechanism fractured. However, it proved possible to operate one side of the incline, of course without the benefit of the counterbalancing, the steam engines taking the whole of the load of the ascending caisson. This was done for the rest of the autumn; even with this serious temporary limitation, 30 boats a day were taken up, a total of 1124 including a few descending, until the beginning of November when the dry season ended.

The total cost of the incline including the land, amounted to £13,500.[12] It was the only canal incline built in Scotland.[1]

Banks burst

The section west of Coatbank Street had given difficulty in construction due to the unstable ground. In 1791 the canal burst its banks and flooded Coats Pit, drowning six miners.[1]

Drumpeller Railway

Contemporary legal sources spell the name "Drumpeller", as does the legal scholar James[note 6] and also contemporary (1858) Ordnance Survey maps; Carter and some other sources spell it "Drumpellar"; Thomson, Hutton and Lindsay spell it "Drumpellier", which is the modern-day spelling of the place name.

Reference has already been made to the numerous feeder tramways to bring minerals to and from the canal where pits and ironworks were close but not immediately adjacent, and the willingness of the Canal Company to form trans-shipment wharfs for railway connections. The tramways were generally made by the pit or ironworks owner on his own land and without requiring Parliamentary authority. There was one exception.[41]

The Drumpeller Railway Company was incorporated under the Monkland Canal (Drumpeller Railway) Act on 4 July 1843 to construct a railway to connect pits at Bankhead to the canal at Cuilhill Gullet, a distance of just under two miles [3 km].[42] The Canal Company had the power to purchase it.[43] It never conveyed passengers: it was "simply a waggonway with such additional status as may be conferred by parliamentary authorisation".[41]

Bankhead (or Braehead) location

James' quotation of Bankhead as the southern terminus is clear, and it is confirmed by Cobb,[44] who shows "Bankhead Siding" at the point where the southern slip road from the A8 road nowadays joins the A752.

Other mapping sources do not show a settlement called at this location. Bankhead farm is about 1 mile (1.6 km) away on the east of the North Calder Water (beyond Waukmill). There is a Braehead in the appropriate location with several mining and claypit works indicated on the 1898 Ordnance Survey map.[45] The exhaustive mines and minerals website Aditnow[46] does not show a coal pit of either name in this vicinity. The southern terminus of the line must be Braehead. The pit there was considerably extended and the Drumpeller had many additional stub branches at the southern end as well as nearer the canal terminal.

General

The railway opened on 3 March 1845, and it had the track gauge of 4 ft 6 in (1,370 mm). The canal at Cuilhill Gullet was on an embankment above the local ground level, and the railway approached on a viaduct and crossed to the north side of the canal. The main line of the canal was diverted to the north of the wharf, forming an island. By 1849 the railway was sending 90 boatloads of coal a year to Glasgow.[1] In 1849 an extension to pits at Tannochside opened.[44]

The land falls considerably from Cuilhill to Braehead – about 100 feet in a mile (20 metres in 1 km) – and Cobb shows two inclined planes in this short section of railway.[44]

It seems that the originally planned extent of the line was not completed in 1845: Braehead is only 1 mile (1.6 km) from Cuilhill; in 1847 the line was extended to Tannochside, and this may be the originally intended southern terminal.

The line ran south-south-east from Cuilhill Gullet (just east of where the present-day M73 crosses the line of the canal) along the line now occupied by Langmuir Road, then curving south-south-west to where Aitkenhead Road roundabout is now.

Evidently the Monkland Canal Company exercised the power to acquire the Railway Company, and with the changes of ownership of the canal itself, the Drumpeller Railway became the property of the Caledonian Railway (CR). The CR changed the track gauge to standard gauge during June 1872 in association with making a connection of the hitherto isolated line to its own network. The connection was a west-to-south curve at Bargeddie station on the Rutherglen and Coatbridge line, giving rail access from the pits.[44]

The pits the line was built to serve were eventually exhausted and the line closed in 1896.[42]

Gartcraig as original western extremity

As described earlier, under James Watt's supervision the canal stopped some distance short of Glasgow. Hutton's description of the exact location is the clearest: "The terminal reached by Watt in 1773 was near Barlinnie and connected to Glasgow by a cart road."[1]

Barlinnie is not noted as a place on the First Edition of the 25-inch Ordnance Survey maps (1858),[47] and the most likely location for the termination seems to be Gartcraig Bridge (sometimes known as Jessie's Bridge), from where access to Glasgow was by way of Carntyne Road. The next possible location would be Smithy Croft bridge, but that is on the Cumbernauld Road; even in 1858 that was not a humble "cart road".

Hume asserts[48] that the temporary end point was a canal basin opposite Barlinnie Prison on the north side of the canal, between Jessie's Bridge (an alternative name for Gartcraig Bridge) and Smithycroft Bridge; he says the basin "is clearly visible on the 2nd edition of the OS 6-inch map (Lanarkshire 1896, sheet viNE)". This is true, but the basin was not shown on the earlier 1858 map, and there was then no road in that vicinity.

The prison was built in 1880 and the canal was used for bringing in building materials.[49] It is likely that the basin was made for that purpose. There is a track from the basin to the prison shown on the later map[50]

Fishing

In the mid-1980s, the canal was stocked with Carp, Roach, Bream, Tench, Perch and some other species. Scottish Canals and North Lanarkshire council maintain the waterway but a permit charge is not currently taken.

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calderbank Basin | 55°50′28″N 3°58′23″W / 55.841°N 3.973°W | NS765626 | Eastern terminus |

| Start of first culvert | 55°51′04″N 3°59′42″W / 55.851°N 3.995°W | NS752638 | |

| Sheepford basin | 55°51′29″N 4°00′11″W / 55.858°N 4.003°W | NS747645 | |

| Blair Road bridge | 55°51′40″N 4°02′42″W / 55.861°N 4.045°W | NS721649 | |

| Start of second culvert | 55°51′40″N 4°04′26″W / 55.861°N 4.074°W | NS702650 | |

| Junction with M8 motorway | 55°51′36″N 4°06′07″W / 55.860°N 4.102°W | NS685650 | |

| Ruchazie | 55°52′08″N 4°09′25″W / 55.869°N 4.157°W | NS651661 | |

| Riddrie | 55°52′26″N 4°11′02″W / 55.874°N 4.184°W | NS634666 | |

| Blackhill | 55°52′16″N 4°12′00″W / 55.871°N 4.200°W | NS624663 | Locks and inclined plane |

| Townhead Basin | 55°52′19″N 4°14′56″W / 55.872°N 4.249°W | NS593666 |

Gallery

North Calder Water dam and source

North Calder Water dam and source Start of the canal

Start of the canal Upper Faskine bridge

Upper Faskine bridge Faskine basin

Faskine basin Lower Faskine bridge

Lower Faskine bridge Seat on towpath Tunnels & Bridges

Seat on towpath Tunnels & Bridges Seat on towpath Vulcan

Seat on towpath Vulcan Caledonian Viaduct

Caledonian Viaduct Road bridge over Sheepford Locks

Road bridge over Sheepford Locks Sheepford Locks artwork

Sheepford Locks artwork Wildlife artwork

Wildlife artwork Canal branch in Summerlee Heritage Park

Canal branch in Summerlee Heritage Park Blair Road bridge

Blair Road bridge King Street from Blair Road bridge

King Street from Blair Road bridge Tow path in Drumpellier Park

Tow path in Drumpellier Park Burginsholme Burn weir

Burginsholme Burn weir Eastern view in Drumpellier Park

Eastern view in Drumpellier Park Eastern view in Drumpellier Park

Eastern view in Drumpellier Park West to Drumpellier Home Farm bridge

West to Drumpellier Home Farm bridge East to Drumpellier Home Farm bridge

East to Drumpellier Home Farm bridge East from Drumpellier Home Farm bridge

East from Drumpellier Home Farm bridge Abandoned Drumpeller Colliery basin

Abandoned Drumpeller Colliery basin Culverted under the North Clyde Line railway

Culverted under the North Clyde Line railway West of the North Clyde Line railway

West of the North Clyde Line railway Culvert at Cuilhill

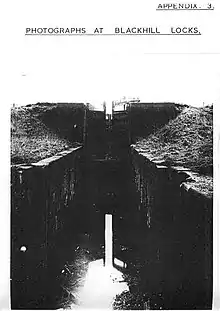

Culvert at Cuilhill Scan of photograph of Blackhill Locks

Scan of photograph of Blackhill Locks Scan of photograph of Blackhill Locks lower basin

Scan of photograph of Blackhill Locks lower basin

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Guthrie Hutton, Monkland: the Canal that Made Money, Richard Stenlake, Ochiltree, 1993, ISBN 1 872074 28 6

- ↑ D O Hill and G F Buchanan, Views of the Opening of the Glasgow and Garnkirk Railway; also an account of that and other Railways in Lanarkshire, Edinburgh, 1832

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Thomson, George (1984) [1945]. The Monkland Canal – a Sketch of the Early History. Monkland Library Services Department. ISBN 978-0-946120-03-1.

- ↑ Canmore, Scotland's National Collection of Buildings, Archaeology and Industry: Castle Street Bridge canmore.rcahms.gov.uk

- ↑ Lumsden, Records of the Trades House of Glasgow, 1713 - 1777, quoted in Thomson 1984

- ↑ James Watt, letter to Dr Small, 12 December 1769, quoted in James Patrick Muirhead, The Life of James Watt, with Selections from his Correspondence, D. Appleton & Co., New York, 1859, page 163

- ↑ James Watt, A Scheme for making a Navigable Canal from the City of Glasgow to the Monkland Collieries, reproduced in Thomson 1984

- ↑ Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Glasgow, Vol 7, p 323, quoted in Thomson 1984

- 1 2 Jean Lindsay, The Canals of Scotland, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1968, ISBN 0-7153-4240-1

- ↑ James Watt, letter to Dr Small, 9 September 1770, quoted in Muirhead, page 164

- ↑ James Watt, letter to Dr Small, December 1770, quoted in Muirhead, page 165

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 James Leslie, Blackhill Canal Inclined Plane, The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal, No 220, Vol XV, July 1852

- 1 2 3 4 Francis H. Groome (editor) Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography, Statistical, Biographical and Historical published in parts by Thomas C. Jack, Edinburgh (1882 to 1885), www.scottish-places.info

- 1 2 Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland, published by, London, S Lewis & Co, 1846

- ↑ Journal of James Watt, reproduced in Thomson 1984

- ↑ Reproduced in Thomson 1984; this quotation is not included in Muirhead

- ↑ Andrew Miller, The Rise and Progress of Coatbridge and Surrounding Neighbourhood, published by David Robertson, Glasgow, 1864, page 4

- ↑ Thomson 1984, p. 22.

- ↑ Advertisements in Glasgow Journal and Glasgow Mercury quoted in Thomson 1984

- ↑ Thomson 1984, p. 19

- 1 2 James Cleland, Annals of Glasgow, Comprising an Account of the Public Buildings, Charities and the Rise and Progress of the City, vol. I, Glasgow, 1816

- 1 2 Robertson, Table 1

- ↑ Thomson 1984, p. 20.

- ↑ Monkland Canal Act, quoted in Thomson 1984, p. 23

- 1 2 Don Martin, The Monkland & Kirkintilloch and Associated Railways, Strathkelvin Public Libraries and Museums, Glasgow, 1995, ISBN 0 904966 41 0

- ↑ Old Session Papers 339, quoted in Thomson 1984

- ↑ Sir John Sinclair, The Statistical Account of Scotland, volume seventh, William Creech, Edinburgh, 1793, page 274

- ↑ Sir John Sinclair, The Statistical Account of Scotland, volume seventh, William Creech, Edinburgh, 1793, pages 383 - 384

- ↑ G Buchanan, An Account of the Glasgow and Garnkirk Railway and Other Railways in Lanarkshire, quoted in The Origins of the Scottish Railway System, 1722 - 1844, C J A Robertson, page 56, John Donald Publishers Limited, Edinburgh, 1983

- ↑ Forth & Clyde Canal Company minutes 6 November 1828, quoted in Robertson

- 1 2 3 4 5 A. Fullarton & Co., The Topographical, Statistical and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland, volume second, Edinburgh, 1847

- ↑ A Slaven, The Development of the West of Scotland, 1750 - 1960, 29-30; and T Grainger and J Miller, Reports to the Proprietors of, and Traders on the Canals and Railways Terminating on the North Quarter of Glasgow [...]; both quoted in Robertson

- ↑ Alastair Ewen, The Monkland Canal www.monklands.co.uk

- ↑ "Monkland Canal". Heritage Paths. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Monkland Canal Walk and Cycle Route www.northlanarkshire.gov.uk

- ↑ A. Fullarton & Co., The Topographical, Statistical and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland, volume first, Edinburgh, 1847

- ↑ Roland Paxton and Jim Shipway, Civil Engineering Heritage: Scotland - Lowlands and Borders, Thomas Telford Ltd (for the Institution of Civil Engineers), 2007, ISBN 978-0-7277-3487-7

- ↑ Permanent International Association of Navigation Congresses, Ship Lifts, Brussels, 1989, ISBN 2-87223-006-8

- ↑ Robert R Goller, The Morris Canal: Across New Jersey by Water and Rail, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston SC, 1999, ISBN 0-7385-0076-3

- ↑ James Leslie, Description of an Inclined Plane, for Conveying Boats over a Summit, to or from different Levels of a Canal, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, volume XIII, 1853–1854, page 206-207

- 1 2 C J A Robertson, The Origins of the Scottish Railway System, 1722 - 1844, John Donald Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh, 1983, ISBN 978-0-85976-088-1

- 1 2 Leslie James, A Chronology of the Construction of Britain's Railways, 1778 - 1855, Ian Allan Ltd, Shepperton, 1983, ISBN 0 7110 1277 6

- ↑ E F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of Great Britain, Cassell and Company, London, 1959

- 1 2 3 4 Col M H Cobb, The Railways of Great Britain – A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Publishing Limited, Shepperton, 2003, ISBN 07110 3003 0

- ↑ Ordnance Survey 25 inch mapping, Lanarkshire, Sheet 007.15, published 1898

- ↑ Aditnow: Mine exploration, photographs and mining history for mine explorers, industrial archaeologists, researchers and historians aditnow.co.uk

- ↑ Ordnance Survey First Edition 25 inch map, Lanark Sheet VII.5 (Combined)

- ↑ J R Hume, J R (1974) Industrial archaeology of Glasgow, Blackie, Glasgow 1974, ISBN 978-0216898332

- ↑ The Glasgow Story www.theglasgowstory.com

- ↑ Ordnance Survey Second Edition Map, Lanarkshire, Sheet 006.08, 1895

Further reading

- Paterson, Len (2005). From Sea To Sea: A History of the Scottish Lowland and Highland Canals. Glasgow: Neil Wilson Publishing. ISBN 1903238943.

Notes

- ↑ In this article, the term "lock" means a single chamber for the elevation or descent of a barge, controlled by a gate or pair of gates at each end

- ↑ The word is usually defined as "tenant" but here it means a person extracting minerals by arrangement on someone else's land

- ↑ The original text reads "Cadder" but this is obviously a printer's error

- ↑ Martin uses an unusual referencing system, citing several references against each note

- ↑ There may have been other examples in Asia

- ↑ Leslie James, not to be confused with the nineteenth-century engineer James Leslie

External links

- Glasgow's Canals Unlocked, tourism publication by Scottish Canals