| Monument to Leonardo da Vinci | |

|---|---|

| |

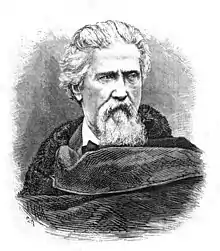

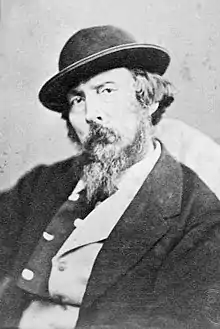

| Artist | Pietro Magni |

| Year | 1858-1872 |

| Medium | Carrara marble |

| Location | Piazza della Scala, Milan |

| 45°28′01″N 9°11′24″E / 45.46698°N 9.190017°E | |

The monument to Leonardo da Vinci is a commemorative sculptural group placed in Milan's Piazza della Scala and unveiled in 1872. On the top is a statue of Leonardo da Vinci while the base depicts four of his pupils as full-length figures, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Marco d'Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto, and Gian Giacomo Caprotti (under the name Andrea Salaino).

The monument was made by sculptor Pietro Magni starting in 1858; due to Milan's transition from the Lombardo-Venetian Kingdom to the Kingdom of Sardinia first and then to the Kingdom of Italy, funding for its construction had problems and delays. After its inauguration it received much negative criticism because of the choice of the place where it was placed and because it was considered a legacy of the Austrian administration.

History

An early project

In 1834, references are found to a "noble and highly cultured fellow citizen of ours" from Milan who intended to create a bronze monument to Leonardo at his own expense.[1] The anonymous person had also obtained permission from the Austrian government to place the monument in Brera's courtyard,[2] decorating the access to the double staircase. Monuments to Cesare Beccaria and Giuseppe Parini were also being prepared for the Richinian staircase at the time.

But the most sumptuous monument for which models are now being made, to be cast in bronze, will be that of the great Leonardo da Vinci, which is being erected by one of our most generous gentlemen at his own expense, not only a lover of fine arts, but professing sculpture for pleasure himself. He did not want the design to be seen or judged until the work was finished, promising to have it completed in three years. Thus all was accepted by the Superiority, who alone will have presented the design to it, and he was granted permission for its placement, in that space of a platform, which divides the two staircases on the ground floor and thus comes to remain in front of the great doorway, in the middle of the facade, so that its view will also be revealed from the street. It is known, however, concerning the design, that it is large and copious in figures, by descriptions interpellated by some, and that it will be very expensive.

The granite base was to have been about 2 meters with bronze figures about 3 meters high, depicting the personification of Immortality in the act of handing a laurel wreath to Leonardo, intent on deep meditations on his books. A bas-relief on the base would have reproduced the Last Supper.[1] However, this project was not completed.

The 1857 competition

In 1856, among the competitions of the Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, the design of a monument to Leonardo in the form of a fountain to be placed in the courtyard of Brera was requested.

A rich honorary monument to Leonardo da Vinci, composed of marble and bronze, serving at the same time as a source of drinking water, to be placed in the Brera palace facing the main gate, and set where the present trumpet stands. The project may be both in drawing and in relief. The drawing will be of the precise measurement of 0.54 meters by 0.81 meters; the model will be 1.08 meters high, and it will be marked how much there is of marble and how much of bronze. Prize = A gold medal of the intrinsic value of twenty sequins.[4]

On Feb. 8, 1857, Emperor Franz Joseph determined that a proper monument should be erected in Piazza San Fedele with a marble statue 3.60 meters high.[5] A new program was therefore established on Oct. 1, 1857, with a deadline of Oct. 31, 1858.[6]

On December 22, 1858, the commission unanimously decided to choose the "Think in marble" model submitted by sculptor Pietro Magni; however, it was also pointed out that it would require an expenditure greater than the 60,000 Austrian liras stipulated in the call for proposals.[7] It was also decided that the monument would be destined for Piazza della Scala.[8]

Construction

Magni set to work, but the outcome of the Second War of Independence forced him to turn first to Urbano Rattazzi, then minister of the interior, and then to Cavour, president of the Council of Ministers.[9] In fact, the government believed that it had no obligation to Magni since the competition had not been approved by the authorities and the amount of expenditure planned for his work was greater than that established by the competition. However, Cavour instructed Massimo d'Azeglio, governor of Milan, to examine the situation in the sculptor's studio and make a decision.[10]

D'Azeglio not only confirmed the design but also suggested essential changes that increased the cost of the monument.

And it was especially following V. E.'s wise observations and suggestions that the thought arose to detach from the monument the said 4 statues of the pupils and to place them on separate pedestals around the monument, thus obtaining a much more homogeneous eurhythmic line. Moreover, having substituted for the primitive model with a round base, the other with an octangular base of pure Bramante style with the addition of the various ornaments, and with the introduction of 4 large bronze bas-reliefs representing scenes from the life and works of the great artist, it was achieved, as the E. V. had also very appropriately suggested, that the monument be given all that majesty and grandeur that was required of it, both because of the importance of the subject and because of the size of the square for which it is intended.

— Pietro Magni to Massimo d'Azeglio, June 20, 1860[11]

Magni left for Bologna as standard-bearer of the National Guard and on his return in 1861 found Giuseppe Pasolini as the new governor; in order to try to obtain confirmation of the commission to build the monument, he thus contacted the Academy, d'Azeglio (who had retired from politics), Governor Pasolini, the mayor of Milan Antonio Beretta and the president of the Council of Ministers Bettino Ricasoli.[12]

A value of about 100,000 liras (corresponding to the 60,000 Austrian liras of the competition plus another 47,000 Italian liras) was estimated for the monument's construction.[13] In 1862 the authorities requested changes to the project to reduce the expense to 90,200 liras, and the City of Milan pledged a contribution of 20,000 liras.[14]

Magni carried on with the monument by incurring expenses for materials; by 1867, however, he had received no payments and the ministerial file had made no progress. He then decided to take advantage of the inauguration of the gallery alongside the Piazza della Scala, scheduled for September 15; he placed a model of the monument at his own expense for the entire month of September, hoping that the authorities, seeing it, would finally allow the work to be completed.[15]

In 1868 he was informed that the government intended to award him only the original amount of the competition, which amounted to about 52,000 Italian liras; even counting the 20,000 for which the municipality of Milan had pledged, he would suffer a net loss of at least 15,000 liras for out-of-pocket expenses.[16]

As a last hope, in 1879 Magni wrote to Filippo Antonio Gualterio, minister of the Royal Household, to try to get the sovereign to intervene, but to no avail.[17] At the same time he was presented with a warning from the Royal State Property Office because he was late in paying rent for the premises he used for his studio; in early 1870 all his models and all his works were seized for auction.[18] Giovanni Battista Brambilla bought them all to return them to the sculptor.[19]

Seeing the impossibility of obtaining what was owed, Magni in August 1870 presented a writ of judicial warning to the Ministry of Public Education.[20] Finally, with the contract signed on March 23, 1871, he managed to obtain a total of 72,000 liras.[21] The amount was less than that allocated for other monuments, such as the one for Carlo Albero in Turin (700,000 liras) or the one for Cavour in Milan (more than 100,000 liras).[21]

According to Ettore Verga, the general hostility toward the monument's construction was not due to the sculptor Magni, but to the monument's origin itself.[22] It was Elia Lombardini, head of the office of public constructions under the Austrian government, who proposed its construction, and it was Lombardini himself who tried to get it accepted after the Unification of Italy by presenting Leonardo as the "true creator of hydraulic science."[23][24]

Inauguration

The monument was unveiled on September 4, 1872 in the presence of Prince Umberto to coincide with the opening in Milan of the first congress of engineers and architects.[25] The National Exhibition of Fine Arts was also underway.

On September 4, the solemn unveiling of the monument to Leonardo da Vinci took place in Milan, erected on the square of the La Scala theater, which presented a marvelous spectacle on that day. In the middle stood the monument all veiled by curtains, with red and white flagpoles around it. In the wide space between it and the theater an elegant white and gold pavilion had been erected, adorned with white and blue draperies and baskets of flowers. The windows and balconies of the houses surrounding the square were adorned with flags and tapestries. The ceremony was very simple and beautiful. At three o'clock in the afternoon Prince Umberto, the mayor, the aldermen, all the members of the Artistic Congress and the members of the Italian Engineers and Architects Congress with other guests went to take their places in the pavilion. The canvases covering the monument then fell, and it suddenly appeared in all its splendor, amid the thunderous applause of the crowded people, and the harmonies of the music of the National band. After the mayor's speech, the minutes were read by which the monument was handed over to the city of Milan, and, after the handover, the band resumed playing the royal march, the guests moved around the monument, followed by the flags of the workers' guilds, and with that the ceremony ended.[26]

In the evening, celebrations were also held in the Cathedral Square with flares. An electric light was projected from a window of the Teatro alla Scala, illuminating the monument in various colors.[27]

In the depictions made on the occasion of the inauguration, the four pedestals with the statues of the students were no longer separate (as planned in earlier versions), but joined to the central octagonal base.

Description

The monument consists of five statues placed on a plinth of pink granite from Baveno, 7.08 meters high.[28] The central body of the plinth has an octagonal shape with unequal sides. Its center is placed in axis with the Vittorio Emanuele II Gallery.

In the center is a 4.40-meter-high marble statue of Leonardo da Vinci.[28] He is portrayed in a pensive pose with his hands clasped to his chest. The name "LEONARDO" is engraved on the front at the foot of the statue; on the back, on the other hand, it says "PIETRO MAGNI FECE."

At a lower level, four pedestals protrude from the short sides of the octagonal plinth on which the other four marble sculptures, 2.60 meters high, stand. They represent four of Leonardo's pupils: Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Marco d'Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto, and Gian Giacomo Caprotti (under the name Andrea Salaino).

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci Giovanni Angelo Boltraffio

Giovanni Angelo Boltraffio Marco d'Oggiono

Marco d'Oggiono Cesare da Sesto

Cesare da Sesto Andrea Salaino

Andrea Salaino

On the major sides of the octagonal plinth, four marble bas-reliefs depict four aspects of Leonardo's life in Milan: Leonardo the painter, who is painting the Last Supper in the Convent attached to the Chiesa delle Grazie; Leonardo the sculptor, who is modeling the equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza; Leonardo the architect and strategist, who is directing the fortifications of Duke Valentino's castles in Romagna; and Leonardo the plumber, who is attending to the pipeline work for the irrigation of Lombardy.[29]

Leonardo the painter

Leonardo the painter Leonardo the sculptor

Leonardo the sculptor Leonardo the architect and strategist

Leonardo the architect and strategist Leonardo the plumber

Leonardo the plumber

Below the bas-reliefs, between the pedestals, is a four-part inscription dictated by Professor Gilberto Govi and engraved in gilded bronze[30] with the dedication:

RINNOVATORE

DELLE ARTI E DELLE SCIENZE

NATO IN VINCI DI VALDARNO

NEL MCCCCLII

MORTO IN CLOUX PRESSO AMBOISE

NEL MDXIX

LUNGAMENTE OSPITE INVIDIATO

IN MILANO, DOVE EBBE

AMICI, DISCEPOLI, GLORIA

IL GIORNO IV DI SETTEMBRE

DEL MDCCCLXXII

QUESTO MONUMENTO

FU POSTO

RENOVATOR

OF THE ARTS AND SCIENCES

BORN IN VINCI DI VALDARNO

IN THE MCCCCLII

DIED IN CLOUX NEAR AMBOISE

IN THE MDXIX

LONG AN ENVIED GUEST

IN MILAN, WHERE HE HAD

FRIENDS, DISCIPLES, GLORY

ON THE FOURTH DAY OF SEPTEMBER

OF MDCCCLXXII

THIS MONUMENT

WAS PLACED."

Criticism

There were varying degrees of negative criticism of the monument, which was not considered Magni's best work;[31] some would have liked Francesco Melzi among the student statues,[32] while others would have preferred to replace them with personifications of mechanics, music, geometry, and philosophy.[33] The pose of the figures, likened to puppets "with their hands hanging down - like hands of lead," was also criticized.[34]

In Piazza della Scala, hands were laid on the foundations of the monument to Vinci. I would have loved to see it placed in the small courtyard of Brera, not in front of an opera house like a singer or music master. The model we saw on the spot, if it is not modified and altered from scratch, was indeed ugly! Magni, who can neither read nor write, made himself famous with his Reading Girl, which he later repeated many dozens of times. A monument to Leonardo required bronze and granite and an artist who understood his art a little better.

— Girolamo d'Adda, December 19, 1871[35]

I swear to everyone that the Leonardo monument is a horror.

One liter in four

The monument's nickname "un litro in quattro" ("one liter in four"), popular in the late 19th century, was due to the resemblance of the monument's five statues to a wine bottle with four glasses around it. Several sources of the time attribute the creation of this nickname to Giuseppe Rovani.[37]

In September 1872, the latter's monument to Leonardo Da Vinci was inaugurated in Piazza della Scala. Everyone knows that Leonardo's statue stands tall in the center. On the four sides of the lower level stand four of his most valiant pupils. The artist heard all kinds of things about his work. Rovani had not yet opened his mouth, and Magni was goading him to speak. Finally, on a certain evening, sitting with four friends at the dinner table of some tavern I no longer know, the artist of the chisel returned to the assault against the artist of the pen so that he would once and for all blurt out. Rovani pleads somewhat, then grabs the liter of wine that towered before them, and places it right in the middle, between the four drinkers, including himself, exclaiming:

— Your monument is here: it's a liter in four!

The laughter went through the roof. But Pietro Magni did not quite cope with the banter. He remembered it and still regretted it many years later.[38]

Interventions

On May 18, 1919, on the occasion of the celebration of the fourth centenary of Leonardo's death, a bronze crown decorated with Vincian knots was added to the foot of the plinth.[39][40]

il 2 maggio 1919

inaugurandosi nel nome

di

LEONARDO

i lavori del porto di milano

il comune pose

on May 2, 1919

it was inaugurated in the name

of

LEONARDO

the works of the port of milan

were conducted by the municipality"

Wrapped monument

In November 1970, as part of the demonstrations to celebrate 10 years of the Nouveau Réalisme movement, Christo and Jeanne-Claude were commissioned by the City of Milan to create a performance. On November 24, the monument to Victor Emmanuel II was wrapped with tarps and tied with red rope; however, due to protests, it was decided to remove the covering the next day. On the same days, the monument to Leonardo da Vinci was also wrapped; on the night of Nov. 28, some young people (apparently neo-fascists) set fire to the tarpaulin, which was removed by firefighters who responded to the scene.[41][42]

See also

References

- 1 2 Monumento 1834, p. 362

- ↑ Appunti, p. 182

- ↑ Borghi, p. 142

- ↑ Concorsi, pp. 51-52

- ↑ Per un monumento, pp. 73-75

- ↑ Il monumento, p. 7

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 7-8

- ↑ Il monumento, p. 13

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 8-11

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 11-12

- ↑ Il monumento, p. 14

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 15-18

- ↑ Il monumento, p. 22

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 24-25

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 29-33

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 34-35

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 35-39

- ↑ Il monumento, pp. 39-43

- ↑ See also obituary in Decessi, p. 691.

- ↑ Il monumento, p. 47

- 1 2 Il monumento, p. 52

- ↑ Verga 1908, pp. 98-101

- ↑ Lombardini, p. iii

- ↑ Cf. Siro Valerio cited in Verga 1908, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Rendiconto, p. 594

- ↑ Inaugurazione, p. 122

- ↑ Le feste di Milano, p. 137

- 1 2 Milano tecnica, p. 302

- ↑ Guida-album, pp. 40-41

- ↑ Monumento 1872a, p. 4

- ↑ Monumento 1872b, p. 326

- ↑ Riccardi, pp. 3-4

- ↑ Soster, p. 249

- ↑ Dossi, p. 186

- ↑ Di Teodoro, p. 165

- ↑ Carducci, p. 329

- ↑ Milano nuova, p. 9

- ↑ Giarelli, p. 45

- ↑ Cronaca, p. 222

- ↑ Verga 1919, pp. 333-334

- ↑ "Wrapped Monuments". Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ↑ Panza.

Bibliography

- "Appunti". Raccolta Vinciana. 8: 175–183. 1912–1913.

- "Concorsi per l'anno 1857". Atti Dell'i.R. Accademia di Belle Arti in Milano: 49–53. 1856.

- "Cronaca del centenario vinciano 1919". Raccolta Vinciana. 11: 221–225. 1920–1922.

- "Decessi". Gazzetta Ufficiale: 691. 18 February 1881.

- Guida-album di Milano e dell'Esposizione, 1906. Milano: Arti grafiche Galileo. 1906 – via archive.org.

- Il monumento di Leonardo da Vinci dello scultore prof. cav. Pietro Magni inaugurato in Milano il giorno 4 settembre 1872. Notizie storiche. Milano. 1872.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Inaugurazione del monumento a Leonardo da Vinci". Emporio Pittoresco (420): 122. September 1872.

- "Le feste di Milano". Emporio Pittoresco (421): 137. September 1872.

- Milano nuova: strenna del Pio Istituto dei Rachitici di Milano. Milano. 1890.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Milano tecnica dal 1859 al 1884. Vol. 1. Milano. 1885.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Monumento a Leonardo da Vinci". Biblioteca Italiana Ossia Giornale di Letteratura Scienze ed Arti: 362–365. 1834.

- "Monumento a Leonardo da Vinci". Il Trentino: 4. 31 August 1872.

- "Monumento a Leonardo da Vinci". L'Illustrazione Popolare: 326. 22 September 1872.

- "Per un monumento a Leonardo da Vinci". Atti Dell'i.R. Accademia di Belle Arti in Milano: 73–75. 1857.

- "Rendiconto delle sedute del primo congresso degli ingegneri ed architetti italiani". Il Politecnico. XX: 593–666. 1872.

- Mino Giacomo Borghi. "Note storiche riguardanti l'Archivio dell'Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera". Rendiconti. Classe di Lettere e Scienze Morali e Storiche. 79.

- Giosuè Carducci (1938). Edizione nazionale delle opere. Lettere. Vol. 7.

- Francesco P. Di Teodoro (1993). "Francesco Uzielli, II: Il Codice Atlantico". Achademia Leonardi Vinci. 6: 161–171.

- Carlo Dossi (1912). Note Azzurre.

- Francesco Giarelli (1896). Vent'anni di giornalismo (1868-1888). Codogno.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Elia Lombardini (1872). Dell'origine e del progresso della scienza idraulica nel Milanese ed in altre parti d'Italia. Milano.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pierluigi Panza (31 July 2020). "Christo a Milano, cinquant'anni fa: quando "impacchettò" il Re e Leonardo". Corriere della Sera.

- Giuseppe Riccardi (1872). Intorno a Leonardo. Studio storico. Milano.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bartolomeo Soster (1873). Dei principii tradizionali delle arti figurative e dei falsi criteri d'oggidì intorno alle arti medesime. Milano.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ettore Verga (1907–1908). "Le vicende del monumento a Leonardo da Vinci in Milano". Raccolta Vinciana. 4: 94–101.

- Ettore Verga (1919). "Il quarto centenario dalla morte di Leonardo da Vinci". Archivio Storico Lombardo: 330–334.