Monumental masonry (also known as memorial masonry) is a kind of stonemasonry focused on the creation, installation and repairs of headstones (also known as gravestones and tombstones) and other memorials.[1]

Cultural significance

In Christian cultures, many families choose to mark the site of a burial of a family member with a gravestone. Typically the gravestone is engraved with information about the deceased person, usually including their name and date of death. Additional information may include date of birth, place of birth and relationships to other people (usually parents, spouses and/or children). Sometimes a verse from the Bible or a short poem is included, generally on a theme relating to love, death, grief, or heaven.

The headstone is typically arranged after the burial. The choice of materials (typically a long-lasting kind of stone, such as marble or granite) and the style and wording of the inscription is negotiated between the monumental mason and the family members. Because of the emotional significance of the headstone to the family members, monumental masons have to be especially sensitive in their dealings with family members, especially in relation to the trade-off between expectations and cost.[1]

%252C_Brighton.jpg.webp)

As a craft

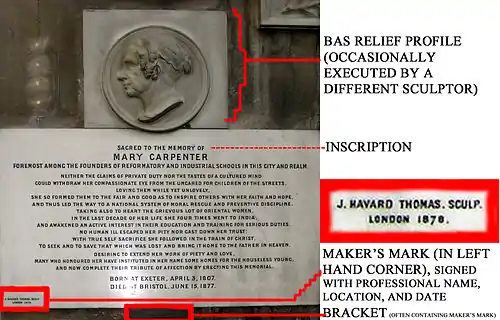

Unlike the work of most stonemasons, the work of the monumental mason is of small size, often just a small slab of stone, but generally with a highly detailed finish. Generally gravestones are highly polished with detailed engraving of text and symbols. Some memorials are more elaborate and may involve the sculpture of symbols associated with death, such as angels, hands joined in prayer, and vases of flowers. Some specially-made stones feature artistic lettering by letter cutters.

By the beginning of the twentieth century the craft had deteriorated to the point that Lawrence Weaver felt compelled to write, "To-day many of the persons who are curiously called 'monumental masons' bring to their task neither educated taste nor the knowledge of good historical examples; they are often, moreover, incompetent in their craftmanship. The more important shops which purvey marble monuments are, if anything, rather worse, for they stereotype bad designs, which are the more offensive because more ambitious and costly. The clerical tailors who sell most of the engraved brasses have mainly succeeded in making that form of memorial the most dreary. All three sources of supply have added a new terror to death."[2]

Monumental masons

References

- 1 2 Monumental Masons

- ↑ Weaver, Lawrence, Memorials and Monuments: Old and New: Two hundred subjects chosen from seven centuries, Published at the offices of "Country Life", London, 1915 p. 1-2