Mor humus is a form of forest floor humus occurring mostly in coniferous forests.[1] Mor humus consists of evergreen needles and woody debris that litter the forest floor. This litter is slow to decompose, in part due to their chemical composition (low pH, low nutrient content), but also because of the generally cool and wet conditions where mor humus is found. This results in low bacterial activity and an absence of earthworms and other soil fauna. Because of this, most of the organic matter decomposition in mor humus is carried out by fungi.

Mor humus is one of three classifications of forest floor humus, along with Moders and Mulls. Each class corresponds to a scale of increasingly colder conditions, decreasing biological diversity and activity, and decreasing nutrient availability.[2] Mor humus ranks at the bottom of this scale and is characterized by very slow decomposition and accumulation of plant material.

Physical characteristics

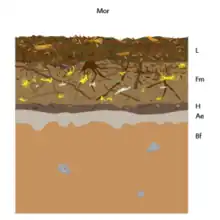

Mor humus has three distinct layers: A litter (L) layer, atop a fermentation (Fm) layer, followed by a humus (H) layer, before the transition to mineral soil (Ae, Bf). Unlike other types of forest floor humus, the litter layer is well-differentiated from the fermentation layer, and the fermentation layer remains distinct from the humus layer.[3] The boundary between mor humus and the mineral horizons below, are very distinguishable from one another.

The litter layer is very thick and is made up of undecomposed organic material. Because it exists under coniferous forests, the litter is composed primarily of evergreen needles, cones, and sticks or other woody debris.

The fermentation layer below consists of plant remains still in varying degrees of decomposition. A layered and compact-matted structure caused by the interweaving of plant roots and fungal hyphae make up the fermentation layer. Through their distinct yellow and white coloration, the fungal hyphae in this horizon are identifiable as cellulose-decomposing fungi which are the primary decomposers of organic matter in mor humus. The plant roots present further contribute more organic residues through exudation.

The humus layer is composed of fully decomposed plant material. Because of the slow and incomplete process of fungal decomposition, the humus layer is very thin. There is very little blending of material between the humus layer and the mineral soil below resulting in the absence of organic matter in the top mineral soil horizon. The roots and fungi From the fermentation layer extend between all three layers and bind them together. Mor humus can be peeled from the soil surface in a manner much like removing a carpet.

Formation

Compared to the litter of deciduous forests, evergreen needles have relatively low nutrient content and a much lower pH. This makes mor humus acidic to very acidic in nature. In coniferous forests containing western red cedar, forest litter can also contain high concentrations of tannins. Tannins such as Tannic acid protect trees from insects attacks and infection and reduce soil pH. All of these factors result in mor humus being an undesirable habitat for soil fauna. Soil bacteria is also unable to metabolize organic matter efficiently when pH is low. Consequently, the majority of decomposition in mor humus is preformed by soil fungi.

In the waterlogged conditions of mor humus, microbes have poor access to oxygen. Therefore, microbial decomposition is very inefficient as the reduction potential may fall below the O2 availability threshold. The decomposition of organic material is considered incomplete. The lack of soil fauna and incomplete decomposition results in the accumulation of undecomposed organic matter which gives rise to mor humus and its distinctive fermentation layer.

Nutrient availability

The high volume of undecomposed organic matter in mor humus leads to a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio and can immobilize important plant nutrients such as nitrogen. The high ratio slows the release of nutrients available to plants. The slow release of nitrogen in mor humus often restricts plant development.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Klinka, K.; Green, R.N.; Trowbridge, R.l; Lowe, L.E. (1981). "Taxonomic classification of humus forms in ecosystems of British Columbia. First approximation" (PDF). Land Management Report Ministry of Forests British Columbia (Canada). 8. ISBN 0-7719-8659-9.

- ↑ Bernier, B (1968). "Descriptive outline of forest humus form classification". Proceedings 7th Meeting of the National Soil Survey Committee of Canada. 39: 154.

- ↑ MacKenzie, M. Derek. "Forest, Range and Wildland Soils" (PDF).

- ↑ Prescott, Cindy E; Maynard, Doug G; Laiho, Raija (August 2000). "Humus in northern forests: friend or foe?". Forest Ecology and Management. 133 (1–2): 23–36. doi:10.1016/s0378-1127(99)00295-9. ISSN 0378-1127.