Morris C. Shumiatcher | |

|---|---|

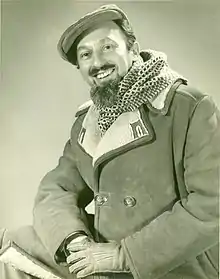

Shumiatcher in 1988 | |

| Born | Morris Cyril Shumiatcher September 20, 1917 |

| Died | September 23, 2004 (aged 87) Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Education | B.A. (1940) and LL.B (1941), University of Alberta LL.M (1942) and Doctorate of Jurisprudence (1945), University of Toronto |

| Occupation(s) | Barrister and solicitor, provincial civil servant |

| Known for | Author of Saskatchewan Bill of Rights (1947), philanthropist, art patron, art collector, author, lecturer |

| Spouse | Jacqueline Shumiatcher |

| Awards | Order of Canada (1981) Saskatchewan Order of Merit (1996) |

Morris Cyril "Shumi" Shumiatcher OC SOM QC (September 20, 1917 – September 23, 2004)[1] was a Canadian lawyer, human rights activist, philanthropist, arts patron, art collector, author, and lecturer. As senior legal counsel in the provincial government of Tommy Douglas, he drafted the 1947 Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, the first such bill in the British Commonwealth. He established a successful private law practice in Regina in 1949 and argued numerous cases of constitutional law before the Supreme Court of Canada. He and his wife Jacqui contributed millions of dollars[2][3] to support the arts, universities, and other charities in Regina, and also amassed "one of the most significant private collections of Inuit art in Canada".[4] He was the recipient of many awards and honours, including the Order of Canada in 1981 and the Saskatchewan Order of Merit in 1997.

Early life and education

Morris Cyril Shumiatcher was born in Calgary, Alberta, to Abraham Isaac Shumiatcher, Q.C. (1890–1974), a lawyer,[5] and his wife Luba (née Lubinsky).[6][7] He had one sister, Minuetta, a concert pianist.[6] He was Jewish.[8]

After attending primary and secondary school in Calgary,[6] he set his career sights on becoming a professor of English. Advised that his religion would restrict his employment opportunities, he pursued a legal education instead.[5] He studied in Japan on a Rotary scholarship from 1940 to 1941 and earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1940 and Bachelor of Laws in 1941 at the University of Alberta. He received his Master of Laws in 1942 from the University of Toronto.[1] He was the first candidate to be accepted into the new doctoral program in law at the University of Toronto in 1942, entitling him to the Rowell Scholarship.[5] World War II intervened, however, and he served with the Royal Canadian Air Force as an air gunner from 1943 to 1945.[9] He completed his doctorate in jurisprudence in 1945 under the supervision of Bora Laskin, submitting the doctoral thesis A Study in Canadian Administrative Law: The Farmers' Creditors Arrangement Acts.[6][5] He was admitted to the bars of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and the Northwest Territories.[6]

Career

In 1946, he moved to Regina, Saskatchewan, at the invitation of Tommy Douglas to become Law Officer of the Attorney General. Afterwards he became the personal assistant to Douglas.[1][9] He drafted several statutes, including the Farm Security Act and the Trade Union Act.[1] He was the legal advisor for the Union of Saskatchewan Indians and chaired a July 1946 meeting between Treaty Indians and the provincial government.[10][11] He continued to advocate for First Nations people with a 1967 article in Saturday Night magazine that criticized the government for restricting them to reserves rather than allowing them to own private property,[12] and with the 1971 publication of his book Welfare: Hidden Backlash: A hard look at the welfare issue in Canada; what it has done to the Indian, what it could do to the rest of Canada.

Shumiatcher authored the 1947 Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, which was the model for the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the Canadian Bill of Rights (1960).[9] The bill – the first of its kind in the British Commonwealth[13] – codified the rights of due process, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of association, and freedom of the press, and included protections against discrimination.[14] Shumiatcher included a protection against gender discrimination, but it did not appear in the final draft.[15] [8]However, the bill lacked an enforcement mechanism, making it "more a symbol than an instrument for defending human rights".[14]

In 1948 he was appointed to the Queen's Counsel, becoming the youngest person in the Commonwealth of Nations to receive that honor.[1][16]

Shumiatcher left government employ in 1949 to start his own legal practice in Regina.[1] Regarded as a "brilliant" lawyer,[2] he specialized in labour, tax, and corporate law[6] and argued numerous cases in constitutional law before the Supreme Court of Canada. His appeal on behalf of Eleanor Ellen Farr in Farr v. Farr (1984) led to changes in Canada's matrimonial property law.[2][17] He represented Joe Borowski before the Supreme Court of Canada in the latter's 1980s challenge to the constitutionality of abortion law; the court declared the case moot in 1989.[18][19]

Other activities

Author and lecturer

Shumiatcher frequently lectured and wrote on "literature, the arts, philosophy, law, human rights and obligations, the monarchy, politics and international relations".[6] He was regularly interviewed in the media and appeared on a current affairs daily radio program; The World in Focus television program; and Civil Liberties and the Law, a lecture series broadcast nationally by the CTV Television Network.[6]

Philanthropist and art patron

Shumiatcher and his wife Jacqueline were prominent supporters of the arts community in Regina, distributing millions of dollars in support of symphonies, theatres, universities, art galleries, and other charities.[2][3] Since his death in 2004, Jacqui continues to make donations in both their names.[3] Their endowments include:

- The Shumiatcher Open Stage at the University of Regina, also known as the Shu-Box, a teaching theatre with expandable seating from 134 to 162[20]

- The Shumiatcher Sculpture Court, featuring Inuit art donated by the couple,[21] and the Shumiatcher Theatre, both at the MacKenzie Art Gallery[3]

- The Shumiatcher Lobby and Shumiatcher Sandbox Series, both at the Globe Theatre[3][22][23]

- The Shumiatcher Pops Series at the Regina Symphony Orchestra[3]

- The Dr. Morris and Jacqui Shumiatcher Scholarship in Law, the annual lecture series "Law and Literature", and the Robert E. Bamford Memorial Award, at the University of Saskatchewan College of Law.[1][24]

- The Drs. Morris and Jacqui Shumiatcher Regina Book Award for the Saskatchewan Book Awards[25]

Dr. Shumiatcher endowed the A.I. Shumiatcher Memorial Prize in Advocacy at the University of Alberta Faculty of Law in honor of his father, Abraham Issac Shumiatcher, Q.C., who attended the university, to be awarded annually to a student who shows superior academic achievement in the field of advocacy.[26]

Art collector

Shumiatcher began collecting art in his twenties; he returned from his study year in Japan in 1941 with "masks, woodblock prints and kimonos".[27] In 1954 he visited Lac la Ronge, northern Saskatchewan, where he purchased four Inuit sculptures. After their marriage in 1955, he and his wife Jacqui amassed what was later termed "one of the most significant private collections of Inuit art in Canada".[4] Their home included an extensive gallery displaying their acquisitions.[3] In 2014 Jacqui donated 1,310 pieces valued at CAD$3 million – including Inuit sculptures and paintings by the Regina Five – to the University of Regina.[28]

Legal challenges, disbarment, and exoneration

Shumiatcher's high profile in Western Canada, fueled by his successful law practice and prominent social status, made him the target of criticism in the legal world, which "perceived [him] as unconventional, flamboyant, and something of a gadfly".[29] In 1962 Shumiatcher was charged with conspiracy to defraud the public as a result of advice he had given a corporate client, and was disbarred.[30] Shumiatcher claimed he was the object of a vendetta by leading politicians and legal personalities whom he had offended.[31] Many Saskatchewan judges supported him.[31] In 1964 the Court of Appeal for Saskatchewan struck down the conviction for conspiracy, citing "manifest error by the trial judge".[31] The court also invalidated Shumiatcher's disbarment, but new allegations received by the Law Society of Saskatchewan prompted the latter group to suspend Shumiatcher's membership for six months beginning in September 1966.[31] Shumiatcher filed a court challenge and in 1967 the Court of Appeal ruled against the Law Society's decision for lack of evidence. The Supreme Court of Canada refused to hear any further appeals, thus ending Shumiatcher's legal challenges.[31]

Affiliations and memberships

Shumiatcher served as president of the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, the Regina Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Commonwealth Society, and the Duke of Edinburgh Award Committee for Saskatchewan. He sat on the board of directors of the Saskatchewan Centre of the Arts and of Beth Jacob Synagogue in Regina. He was also a member of the National Council of the Canadian Bar Association and was an honorary solicitor of the Regina Press Club.[1]

Honours and awards

Shumiatcher served as an honorary consul general for Japan and Dean of the Consular Corps for Saskatchewan for 14 years.[1]

He was appointed a Queen's Counsel and was the recipient of numerous honours and awards on the provincial and government levels, including the Order of Canada (1981), the B'nai Brith Citizen of the Year (1991), the Canada 125 Medal (1992), the Distinguished Service Award of the Canadian Bar Association (1995), and the Saskatchewan Order of Merit (1996).[1][32][33] He was honoured with life membership in the Monarchist League of Canada in 1992[34] and in the Regina Bar Association in 1997.[1]

Personal life

In 1947 Jacqueline "Jacqui" Fanchette Clotilde Clay was hired as secretary to Shumiatcher during his employ as senior legal counsel in the provincial government; after leaving this position, she helped set up his private law practice.[35] They married in April 1955.[3][6] Jacqui established a managerial company to handle staff hires and office management for Morris' law firm.[3]

The couple were childless.[3] They resided at 2520 College Avenue in Regina, purchasing in 1956 a two-story Picturesque Eclectic house originally owned by Maughan McCausland, also a lawyer.[3][36] In 1979 they adjoined an adjacent one-story house to the property, creating one large structure.[3][36] Like her husband, Jacqui was awarded the Saskatchewan Order of Merit in 2001[6] and was inducted into the Order of Canada in 2017.[37]

Shumiatcher died on September 23, 2004.[38] His papers are held at the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan.[6]

Bibliography

Shumiatcher authored three books:[6]

- Assault on Freedom: Reflections on Saskatchewan's medical care crisis. 1962.

- Welfare: Hidden Backlash: A hard look at the welfare issue in Canada; what it has done to the Indian, what it could do to the rest of Canada. McClelland and Stewart. 1971. ISBN 9780771083570.

- Man of Law: A Model. Western Producer Prairie Books. 1979. ISBN 0888330340.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Coneghan, Daria (2006). "SHUMIATCHER, MORRIS CYRIL (1917–2004)". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Regina lawyer and philanthropist dead at 87". CBC News. 24 September 2004. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Seiberling, Irene (17 July 2013). "Patron of the arts believes in sharing the wealth". Leader-Post. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Love At First Sight: The Drs. Morris & Jacqui Shumiatcher Art Collection". MacKenzie Art Gallery. 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Girard 2005, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Fonds F 3 - Morris and Jacqui Shumiatcher fonds". Saskatchewan Council for Archives and Archivists. 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Archives Society of Alberta|url=https://albertaonrecord.ca/shumiatcher-abraham-isaac

- 1 2 Patrias 2012, p. 188.

- 1 2 3 Harasen 2016, p. 80.

- ↑ Barron 2011, p. 42.

- ↑ Ens & Sawchuk 2016, p. 301.

- ↑ Haycock 1972, p. 87.

- ↑ "Aaron Fox talks about Dr. Morris Shumiatcher (video)". reginacity.com. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- 1 2 Clément 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ Clément 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ "Exceptional Builders". Canadian Jewish Experience. 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "Supreme Court of Canada - Farr v. Farr, [1984] 1 S.C.R. 252". LexUM. 3 May 1984. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Ruggiero 2008, p. 177.

- ↑ Fraser 2014, p. 118.

- ↑ "Shumiatcher Open Stage". University of Regina. 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "Exhibitions". MacKenzie Art Gallery. 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "About the Shumiatcher Sandbox Series". Globe Theatre. 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Margoshes, Dave (27 November 2008). "Arts Patrons, Impresarios, and Philanthropists in Saskatchewan – Part 4: Jacqui Shumiatcher". Saskatchewan Arts Alliance. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ Conroy, Sean (15 November 2016). "National Philanthropy Day: An honored supporter". University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "Drs. Morris and Jacqui Shumiatcher Regina Book Award". Saskatchewan Book Awards. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ University of Alberta|url=https://www.registrar.ualberta.ca/ro.cfm?id=536

- ↑ Tushabe, Iryn (2015). "Love At First Sight: A glimpse at the Shumiatchers as art collectors". Saskatchewan NAC.

- ↑ "U of R gets amazing gift of art from Shumiatcher collection". CBC News. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Girard 2005, p. 311.

- ↑ Girard 2005, pp. 311–2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Girard 2005, p. 312.

- ↑ "Distinguished Service Award". The Canadian Bar Association. 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Saskatchewan Order of Merit". Government of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Honorary Life Memberships". Monarchist League of Canada. 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Jacqui Clay Shumiatcher". North Central Regina History Project. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Regina Walking Tours: Centre Square Area" (PDF). City of Regina. p. 36. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "3 from Sask. among latest Order of Canada appointees". CBC Radio. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details".

Sources

- Barron, F. Laurie (2011). Walking in Indian Moccasins: The Native Policies of Tommy Douglas and the CCF. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0774841924.

- Clément, Dominique (2009). Canada's Rights Revolution: Social Movements and Social Change, 1937-82. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0774858434.

- Clément, Dominique (2014). Equality Deferred: Sex Discrimination and British Columbia's Human Rights State, 1953-84. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0774827515.

- Ens, Gerhard J.; Sawchuk, Joe (2016). From New Peoples to New Nations: Aspects of Metis History and Identity from the Eighteenth to the Twenty-first Centuries. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442627116.

- Girard, Philip (2005). Bora Laskin: Bringing law to life. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802090443.

- Fraser, Marian Botsford (2014). Acting for Freedom: Fifty Years of Civil Liberties in Canada. Second Story Press. ISBN 978-1927583500.

- Harasen, Lorne (2016). The Harasen Line: A Broadcaster's Memoir. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1460283462.

- Haycock, Ronald Graham (1972). The Image of the Indian (Reprint ed.). Waterloo Lutheran University. ISBN 9780889208667.

- Patrias, Carmela (2012). Jobs and Justice: Fighting Discrimination in Wartime Canada, 1939-1945. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442642362.

- Ruggiero, Cristina Marie (2008). The construction of judicial power in a federal system: Lessons from Canada, United States and Germany. University of Wisconsin—Madison.

- Shumiatcher, Morris Cyril (1979). Man of Law, a Model. Western Producer Prairie Books. ISBN 0888330286. ISBN 978-0888330284.