Muhajir culture (Urdu: مہاجر ثقافت) is the culture of the various Muslims of different ethnicities who migrated mainly from North India (after the partition of British India and subsequent establishment of the Dominion of Pakistan) in 1947 generally to Karachi, the federal capital of Pakistan and before 1947 Karachi is the capital of Sindh. They consist of various ethnicities and linguistic groups.[1] The Muhajirs are mainly concentrated in Karachi and Hyderabad.

Cultural History

Early history of the Muhajir community

The roots of Muhajirs lie with Muslim migration and settlement in various parts of especially modern Gujarat, East Punjab, Bihar, Rajesthan and Uttar Pradesh. The conversion of natives to Islam and the migration of Muslims from the Muslim World coalesced to form the Urdu Muslim community which was referred to as Hindustani Musalmans, East Punjab. Early settlement of Northern Muslims was due to the migrations and then establishment of Turkish Sultanate.[3] In medieval times, the term Hindustani Musalman was applied to those Muslims who were either converts to Islam or whose ancestors migrated and settled in Delhi Sultanate. These Hindustani Musalmans did not form a single community, as they were divided by ethnic, linguistic and economic differences. Often these early settlers lived in fortified towns, known as Qasbahs. With the rise of the barbaric Mongols hordes under Genghis Khan which committed massacres and genocides in Central Asia and Middle East, there was an influx of Muslim refugees into the Delhi Sultanate, many of whom settled in the provincial qasbas, bringing with them an Arabo-Persianized culture. Many of these early settlers are the ancestors of the Sayyid and Shaikh communities. In these qasbas, over time a number of cultural norms arose, which still typify many North Indian Muslim traditions. The Turkish Sultans of Delhi and their Mughal successors patronized the émigré Muslim culture: Islamic jurists of the Sunni Hanafi school, Persian literati who were Shia Ithnā‘ashariyyah and Sufis of several orders, including the Chishti, Qadiri and Naqshbandi. These Sufi orders were particularly important in converting Hindus to Islam.

Since the time of the Muslim conquests, the eastern region of the Indus river has been referred to as Hind and later Hindustan.[4] For example, the army of Ghiyas ud din Balban was referred to as "Hindustani" troops, who were attacked by the "Hindus".[5] This was continued by the Mughal Empire, where Muslim Indians were referred to as Hindustanis, while non-Muslim Indians were referred to as Hindus.[6]

Millions of natives converted to Islam during the Muslim rule. Lodi dynasty was dominated by the Pashtuns soldiers from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Afghanistan who settled in the northern India. After the Battle of Panipat (1526) Mughal Emperor Babur defeated the Lodi dynasty with Tajik, Chagatai and Uzbek soldiers and nobility. These Central Asian Turk soldiers and nobles were awarded estates and they settled with their families in the northern India. These diverse ethnic, cultural and linguistic groups merged over the centuries to the form Urdu speaking Muslims of South Asia.

The Barha Sayyid tribe of Indian Muslims of the Doab, due to their reputation for bravery, traditionally composed the vanguard of the Mughal imperial armies, to which they held the hereditary right in every battle.[7][8] After the death of Aurangzeb, the Barhas became kingmakers in the Mughal empire under Qutub-ul-Mulk and Ihtisham-ul-Mulk, creating and deposing Mughal emperors at will.[9]

The Rohilla leader Daud Khan was awarded the Katehar (later called Rohilkhand) region in the then northern India by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir (ruled 1658-1707) to suppress the Rajput uprisings, which had afflicted this region. Originally, some 20,000 soldiers from various Pashtun tribes (Yusafzai, Ghori, Ghilzai, Barech, Marwat, Durrani, Tareen, Kakar, Naghar, Afridi and Khattak) were hired by Mughals to provide soldiers to the Mughal armies. Their performance was appreciated by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, and an additional force of 25,000 Pashtuns were recruited from modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Afghanistan and were given respected positions in Mughal Army. Nearly all of Pashtuns settled in the Katehar region and also brought their families from modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Afghanistan. In 1739, a new wave of Pashtuns settled increasing their population to over 1,000,000. After the Third Battle of Panipat fought in 1761 between the Ahmad Shah Durrani and Maratha Empire thousands of Muslim Pashtun, Punjabi and Baloch soldiers settled in the northern India. These diverse ethnic, cultural and linguistic groups merged over the centuries to the form the Urdu speaking Muslims of South Asia.

It is estimated that about 30% of Urdu speakers are of Pashtun origin. The provinces such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar had significant population of Pashtuns. These Pashtuns over the years lost their language Pashto and culture and adopted Urdu as their first language. Sub-groups also includes the Hyderabadi Muslims, Memon Muslims, Bihari Muslims etc. who keep many of their unique cultural traditions.[10] Muslims from what are now the states of Delhi, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Later history of Muhajir community

When the Mughal Empire disintegrated, their territory remained confined to the Doab region of and Delhi. Other areas of today's Northern India (Uttar Pradesh or U.P.) were now ruled by different rulers: Oudh was ruled by the Shia Nawabs of Oudh, Rohilkhand by the Rohillas, Bundelkhand by the Marathas and Benaras by its own king, while Nepal controlled Kumaon-Garhwal as a part of Greater Nepal. The state's capital city of Lucknow was established by the Muslim Nawabs of Oudh in the 18th century. It became an important centre of Muslim culture, and the centre for the development of Urdu literature.[11][12]

By the early 19th Century, the British had established their control over what is now Uttar Pradesh. This led to an end of almost eight centuries of Muslim rule over Uttar Pradesh. The British rulers created a class of feudal landowners who were generally referred to as zamindars, and in Awadh as taluqdars. Many of these large landowners provided patronage to the arts, and funded many of the early Muslim educational institutions. A major educational institution was the Aligarh Muslim University, which gave its name to the Aligarh movement. Under the guidance of Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan, the Urdu speaking Muslim elite sought to retain their position of political and administrative importance by reconciling their Mughal and Islamic culture with English education. A somewhat different educational movement was led by the Ulema of Deoband, who founded a religious school or Dar-ul-Uloom designed to revitalize Islamic learning. The aim of the Deobandis, as the movement became known as was to purge the Muslims of all strata of traditions and customs that were claimed to be Hindu.

The role of Urdu language played an important role in the development of Muslim self-consciousness in the early twentieth century. Urdu speaking Muslims set up Anjumans or associations for the protection and promotion of Urdu. These early Muslim associations formed the nucleus of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka in 1905. Many of the leaders belonged to the Ashraf category. Urdu speaking Muslims formed the core of the movement for a separate Muslim state, later known as Pakistan. The eventual effect of this movement led to the Pakistan Movement, and independence of Pakistan. This led to an exodus of many Muslim professionals to Pakistan, and the division of the Urdu speaking Muslims, with the formation of the Muhajir ethnic group of Pakistan. The role of the Aligarh Muslim University was extremely important in the creation of Pakistan.[13]

Modern history of the Muhajir community

The independence of Pakistan in 1947 saw the settlement of Muslim from India especially from the part of Punjab that became a state of India following the end of the British Raj. The Muslim migrants left behind all their land and properties in India when they migrated and some were partly compensated by properties left by Hindus that fled from Pakistan to India to escape the communal violence. The Muslim Bengalis, Gujaratis, Konkanis, Hyderabadis, Marathis, Rajasthanis and Biharis fled India and settled in Karachi. There is also a sizable community of Malayali Muslims in Karachi (the Mappila), originally from Kerala in South India.[14] There is also a sizable community of people of Tamil Muslim heritage. The non-Urdu speaking Muslim refugees from India now speak the Urdu language and have assimilated into the wider community of Muhajirs.

Muhajir culture is the culture of Muslim nation that migrated mainly from North India after the independence of Pakistan in 1947 generally to Karachi.[15] The Muhajir culture refers to the Pakistani variation of Indo-Islamic culture and part of the Culture of Karachi city in Pakistan.[16][17] It is a blend of Delhi, Hyderabad, Bengali, Bihari, and Uttar Pradesh cultures.[18][19] The core characteristics of Muhajir cultural identity are considered Urdu, education, resistance, urbanism. This variation of culture came into existence mainly after the ethnic riots of 1970s.[20][21]

Language

Urdu is an Indo-Aryan language spoken by Urdu-speaking people, chiefly in North India and Karachi.[22][23] Urdu is spoken by majority of muhajirs, and is considered the culture language of muhajirs.[24] It is the national language and lingua franca of Pakistan, where it is also an official language alongside English.[25][26][27]

Urdu has been described as a Persianised register of the Hindustani language;[28][29] Urdu and Hindi share a common Sanskrit- and Prakrit-derived vocabulary base, phonology, syntax, and grammar, making them mutually intelligible during colloquial communication.[30][31] While formal Urdu draws literary, political, and technical vocabulary from Persian,[32] formal Hindi draws these aspects from Sanskrit; consequently, the two languages' mutual intelligibility effectively decreases as the factor of formality increases.

Urdu became a literary language in the 18th century and two similar standard forms came into existence in Delhi and Lucknow. Since the partition of India in 1947, a third standard has arisen in the Pakistani city of Karachi.[33][34] According to the World Economic Forum, today, Urdu along with Hindi is considered the eighth most powerful language in the world and the most powerful in modern South Asia, due to the influence on the language of other south asian languages.[35]

Cuisine

Muhajir cuisine refers to the cuisine of the muhajir people and is covered under both Indian and Pakistani cuisines.[36] Muhajirs, after arriving in Karachi, have revived their old culture, including numerous desserts, savory dishes, and beverages.[37][38] The Mughal and Indo-Iranian heritage played an influential role in the making of their cuisine and therefore Muhajir cuisine tends to use royal cuisine specific to the old royal dynasties of now defunct states in ancient India.[39] Curry, biryani and Paan are the central dishes of muhajir cuisine.[40][41][42] While less known dishes include Korma, kofta, Seekh kebab, Nihari, Haleem, Nargisi Koftay, Roghani Naan, naan, Sheer khurma, and Tea.[43][44]

Traditional dress

The traditional clothing of Muhajirs is the traditional clothing worn by Muslims in North India, and it has both Muslim and South Asian influences. Both Muslim men and women wear the shalwar kameez as a daily dress,[45] and kurta, pyjama and brightly-coloured waistcoats for special occasions.[46] Other traditional dresses for muhajirs include the sherwani, which is believed to have been introduced to Pakistan by Muhajirs,[47] sari, which is an un-stitched stretch of woven fabric arranged over the body like a robe[48][49] and Gharara which originated from the Nawabs' attempt to imitate the British evening gown.[50]

Literature and poetry

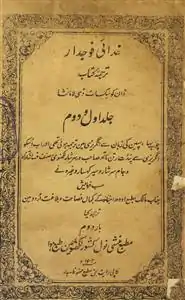

The majority of Muhajirs speak Urdu as their native tongue, therefore most poets and writers write in Urdu.[51][52] Urdu literature, is composed of oral and written scripts and texts in the Urdu language in the form of poetry such as, Ghazals and Nazms and prose such as, dastans.[53] There is a very rich tradition of Urdu literature and poetry running through the history of Muhajir culture.[54] Poetry is the most important part of Urdu literature, and due to this Urdu is widely perceived as a language of poetry.[55] Many aspects of Urdu poetry such as mushaira, a poetic symposium in which ghazals are recited, are considered some of the most important aspects of muhajir culture.[56][57]

Urdu literature originated some time around the 14th century in present-day North India among the sophisticated gentry of the courts.[53] The continuing traditions of Islam and patronisations of foreign culture centuries earlier by Muslim rulers, usually of Turkic or Afghan descent, marked their influence on the Urdu language given that both cultural heritages were strongly present throughout Urdu-speaking territory.[53] Urdu's poetry took its final shape in the 17th century when it was declared the official language of the court,[58] while literary prose started with the penning of Sabras in the year 1635 — in Deccan, by Mulla Asadullah Wajhi on the orders of Abdullah Qutb Shah.[59]

Urdu literature heavily influenced the muhajir identity, but in turn was influenced by it. In the 1930s, Urdu press emerged as a strong antithesis to the anti-Muslim League political discourse. Urdu press emboldened young and educated Muslims of northern India to resist colonial oppression and question Congress’s dual policy of supporting secularism and opposing democratic autonomy to Muslim-majority areas.[60] Zafar Ali Khan declared Pakistan "a homeland for Urdu journalism," and later encouraged muslims to migrate there.[61] Migration, displacement, nostalgia, homecoming, and reclamation were introduced to Urdu literature after 1947 and they constitute the themes of most Urdu literature written since the early 1960s.[62]

Festivals

Festivals celebrated by Muhajirs include religious, political, ethnic, and national festivals. Islamic festivals which are celebrated by Muhajirs include Eid-al-Fitr celebrated to mark the end of the month-long dawn-to-sunset fasting of Ramadan, Eid-al-Adha to honour the willingness of Abraham (Ibrahim) to sacrifice his son Ishmael (Ismail) as an act of obedience to God's command, and Ashoura to mourn the death of Husayn ibn Ali and celebrate the day of salvation for Moses and the Israelites from Biblical Egypt.[63] Political celebrations include MQM Founding Day celebrated to mark the founding of the first Muhajir nationalist party Muttahida Qaumi Movement, believed to be the architect of Muhajir identity, and APMSO Founding Day celebrated to mark the founding of the first Muhajir nationalist student union All Pakistan Muhajir Students Organization.[64][65][66] Muhajirs celebrate Muhajir Cultural Day as an ethnic and cultural festival.[67] To celebrate this day, rallies depart from all areas of Karachi to Mazar-e-Quaid, and political parties and civil society organisations set up their camps to welcome participants in the rally and to express solidarity.[68]

See also

References

- ↑ The crisis of Mohajir identity Harris Khalique. The News International.

- ↑ Jamal Malik (2008). Islam in South Asia: A Short History. Brill Publishers. p. 104.

- ↑ Sareen, Kriti M. Shah and Sushant. "The Mohajir: Identity and politics in multiethnic Pakistan". ORF. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ↑ Brard, Gurnam Singh Sidhu. "East of Indus: My memories of old Punjab." (2007)

- ↑ Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate:A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Satish Chandra. "Parties And Politics At The Mughal Court".

- ↑ William Irvine (1971). Later Mughal. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 202.

- ↑ Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research (1975). Journal of the Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research: Volume 12. Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 193. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ↑ Karen Isaksen Leonard, Locating home: India's Hyderabadis abroad

- ↑ The Rise and Decline of the Ruhela by Iqbal Hussain

- ↑ The crisis of empire in Mughal north India : Awadh and the Punjab, 1707-48 / Muzaffar Alam

- ↑ Separatism among Indian Muslims : the politics of the United Provinces' Muslims 1860-1923 / Francis Robinson

- ↑ "DNA India | Latest News, Live Breaking News on India, Politics, World, Business, Sports, Bollywood". DNA India. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ↑ Bhutto, Salima (2021-12-24). "What is Muhajir Culture Day?". MM News TV. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ↑ Sareen, Kriti M. Shah and Sushant. "The Mohajir: Identity and politics in multiethnic Pakistan". ORF. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ↑ "Heritage Sites of Karachi". DAILY NEWS e-paper. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ↑ "Pakistan: welcome to kaleidoscopic Karachi". gulfnews.com. 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2023-05-21.

- ↑ Journal of the Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research. Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research. 1975.

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (2012-08-30). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-660-7.

- ↑ Kaur, Ravinder (2005-11-05). Religion, Violence and Political Mobilisation in South Asia. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-3430-1.

- ↑ "Urdu language". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

member of the Indo-Aryan group within the Indo-European family of languages. Urdu is spoken as a first language by nearly 70 million people and as a second language by more than 100 million people, predominantly in Pakistan and India. It is the official state language of Pakistan and is also officially recognized, or "scheduled," in the constitution of India.

- ↑ "Urdu (n)". Oxford English Dictionary. June 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

An Indo-Aryan language of northern South Asia (now esp. Pakistan), closely related to Hindi but written in a modified form of the Arabic script and having many loanwords from Persian and Arabic.

- ↑ Robinson, Rowena (2004-02-20). Sociology of Religion in India. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-9781-8.

- ↑ Gazzola, Michele; Wickström, Bengt-Arne (2016). The Economics of Language Policy. MIT Press. pp. 469–. ISBN 978-0-262-03470-8. Quote: "The Eighth Schedule recognizes India's national languages as including the major regional languages as well as others, such as Sanskrit and Urdu, which contribute to India's cultural heritage. ... The original list of fourteen languages in the Eighth Schedule at the time of the adoption of the Constitution in 1949 has now grown to twenty-two."

- ↑ Groff, Cynthia (2017). The Ecology of Language in Multilingual India: Voices of Women and Educators in the Himalayan Foothills. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-137-51961-0. Quote: "As Mahapatra says: “It is generally believed that the significance for the Eighth Schedule lies in providing a list of languages from which Hindi is directed to draw the appropriate forms, style and expressions for its enrichment” ... Being recognized in the Constitution, however, has had significant relevance for a language's status and functions.

- ↑ Muzaffar, Sharmin; Behera, Pitambar (2014). "Error analysis of the Urdu verb markers: a comparative study on Google and Bing machine translation platforms". Aligarh Journal of Linguistics. 4 (1–2): 1.

Modern Standard Urdu, a register of the Hindustani language, is the national language, lingua-franca and is one of the two official languages along with English in Pakistan and is spoken in all over the world. It is also one of the 22 scheduled languages and officially recognized languages in the Constitution of India and has been conferred the status of the official language in many Indian states of Bihar, Telangana, Jammu, and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and New Delhi. Urdu is one of the members of the new or modern Indo-Aryan language group within the Indo-European family of languages.

- ↑ Gibson, Mary (13 May 2011). Indian Angles: English Verse in Colonial India from Jones to Tagore. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0821443583.

Bayly's description of Hindustani (roughly Hindi/Urdu) is helpful here; he uses the term Urdu to represent "the more refined and Persianised form of the common north Indian language Hindustani" (Empire and Information, 193); Bayly more or less follows the late eighteenth-century scholar Sirajuddin Ali Arzu, who proposed a typology of language that ran from "pure Sanskrit, through popular and regional variations of Hindustani to Urdu, which incorporated many loan words from Persian and Arabic. His emphasis on the unity of languages reflected the view of the Sanskrit grammarians and also affirmed the linguistic unity of the north Indian ecumene. What emerged was a kind of register of language types that were appropriate to different conditions. ...But the abiding impression is of linguistic plurality running through the whole society and an easier adaptation to circumstances in both spoken and written speech" (193). The more Persianized the language, the more likely it was to be written in Arabic script; the more Sanskritized the language; the more likely it was to be written in Devanagari.

- ↑ Basu, Manisha (2017). The Rhetoric of Hindutva. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107149878.

Urdu, like Hindi, was a standardized register of the Hindustani language deriving from the Dehlavi dialect and emerged in the eighteenth century under the rule of the late Mughals.

- ↑ Gube, Jan; Gao, Fang (2019). Education, Ethnicity and Equity in the Multilingual Asian Context. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-981-13-3125-1.

The national language of India and Pakistan 'Standard Urdu' is mutually intelligible with 'Standard Hindi' because both languages share the same Indic base and are all but indistinguishable in phonology.

- ↑ Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. p. 385. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

With the consolidation of the different linguistic bases of Khari Boli there were three distinct varieties of Hindi-Urdu: the High Hindi with predominant Sanskrit vocabulary, the High-Urdu with predominant Perso-Arabic vocabulary and casual or colloquial Hindustani which was commonly spoken among both the Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of north India. The last phase of the emergence of Hindi and Urdu as pluricentric national varieties extends from the late 1920s till the partition of India in 1947.

- ↑ Kiss, Tibor; Alexiadou, Artemis (10 March 2015). Syntax – Theory and Analysis. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 1479. ISBN 978-3-11-036368-5.

- ↑ Schmidt, Ruth Laila (8 December 2005). Urdu: An Essential Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-71319-6.

Historically, Urdu developed from the sub-regional language of the Delhi area, which became a literary language in the eighteenth century. Two quite similar standard forms of the language developed in Delhi, and in Lucknow in modern Uttar Pradesh. Since 1947, a third form, Karachi standard Urdu, has evolved.

- ↑ Mahapatra, B. P. (1989). Constitutional languages. Presses Université Laval. ISBN 978-2-7637-7186-1.

- ↑ "These are the most powerful languages in the world". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Tariq, Minahil (2014-12-08). "Different cultures of Pakistan: MUHAJIR CUISINE". Different cultures of Pakistan. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- ↑ Sen, Madhurima (2019-03-24). "Nostalgia in Intizar Hussain's 'The Sea Lies Ahead': Muhajirs as a Diasporic Community". Research Gate. Archived from the original on 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ↑ "In the homes of Pakistan's Memons, age-old recipes bring nostalgia to Ramadan tables". Arab News. 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- ↑ Chaudry, Rabia (2022-11-08). Fatty Fatty Boom Boom: A Memoir of Food, Fat, and Family. Algonquin Books. ISBN 978-1-64375-343-0.

- ↑ "Pakistani food debate: Team Biryani Vs Team Pulao, who will win?". gulfnews.com. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ↑ Chattha, Ilyas (2022-06-16). The Punjab Borderland: Mobility, Materiality, and Militancy, 1947–1987. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-51795-6.

- ↑ "A fiery fusion". gulfnews.com. 2011-08-14. Archived from the original on 2023-05-21. Retrieved 2023-05-21.

- ↑ "What dishes are common in Muhajir cuisine?". Answers. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ↑ Falah, Gulzar (2021-05-02). "Biryani, Lahori fish, pulao ... Pakistani cuisine and its presence in the UAE". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ↑ Raka Shome (2014). Diana and Beyond: White Femininity, National Identity, and Contemporary Media Culture. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252096686.

- ↑ "Mohajir Culture Day celebrated in city". Dawn. 2021-12-25. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Niraalee Shah (2021). Indian Etiquette: A Glimpse Into India's Culture. Notion Press. ISBN 9781638865544.

- ↑ Boulanger, Chantal (1997). Saris: an illustrated guide to the Indian art of draping. Shakti Press International. p. 55. ISBN 9780966149616.

- ↑ Jermsawatdi, Promsak (1979). Thai Art with Indian Influences. ISBN 9788170170907.

- ↑ H.r. Nevill (1884). The Lucknow Omnibus. p. 177.

- ↑ Majeed, Gulshan. "Ethnicity and Ethnic Conflict in Pakistan" (PDF). Journal of Political Studies. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ↑ R. Upadhyay. 'Urdu Controversy – is dividing the nation further'. South Asia Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- 1 2 3 Bailey, T. Grahame (April 1930). "Urdu: the Name and the Language". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 62 (2): 391–400. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00070702. ISSN 2051-2066. S2CID 163263547.

- ↑ "For Love of Urdu: Language and the Legacies of Jinnah and Nehru". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ Parekh, Rauf (2022-10-03). "Literary notes: Is Urdu just a sweet-sounding poetic language?". Dawn. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ "Mushaira is part of Muhajir culture, says Tessori". Dawn. 2022-12-19. Retrieved 2023-01-15.

- ↑ "Mehfil-e-Mushaira – History of Ghazal". Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Urdu Poetry". Niazi. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ Parekh, Rauf (2022-09-12). "Literary notes: Sabras: the earliest book of literary prose in Urdu". Dawn. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ "Urdu Press and the Pakistan Movement". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ↑ "Pioneers of Urdu journalism". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ↑ "Urdu literature after the Partition | Literati | thenews.com.pk". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ↑ "Karachi Festivals – Karachi Annual Events". www.karachi.com. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ↑ "English Newspaper Coverage : 32nd foundation day of Mqm". www.mqm.org. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ↑ "Mr. Altaf Hussain congratulates to all his loyalist comrades and the nation on 43rd foundation day of APMSO". www.mqm.org. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ↑ "APMSO Foundation Day marked". Saudigazette. 2016-06-28. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ↑ "Muhajir Culture Day celebrated". The Express Tribune. 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ↑ "Muhajir Culture Day celebrated". Dawn. 2022-12-25. Retrieved 2023-03-07.