Municipio Roma III | |

|---|---|

Municipio of Rome | |

An ATAC trolleybus in Via Nomentana just south of Piazza Sempione. | |

Flag | |

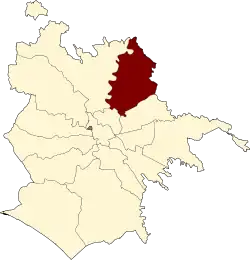

location of the municipio within the municipality of Rome. | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Lazio |

| Comune | Rome |

| Government | |

| • President | Paolo Emilio Marchionne (Democratic Party) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,782 km2 (3,777 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 205,019 |

| • Density | 209,592/km2 (542,840/sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Dialling code | 06 |

Municipio Roma III is the third administrative subdivision of Rome (Italy).

It was established by the Capitoline Assembly, with Resolution No. 11 of 11 March 2013, which replaced the previous Municipio Roma IV (formerly "Circoscrizione IV").

Geography

Municipio III is in the north of the city and is the sixth largest, with 97.818 km2.[2]

To the south, it borders Municipio II and Municipio IV, to the west Municipio XV, along the river Tiber, and the comuni of Riano, Monterotondo, Mentana and Fonte Nuova to the north-east.

The territory is mainly hilly; the southern area comprising the main urban aggregates is contrasted by the northern area, characterized by a rural environment, mostly included in the Marcigliana nature reserve.

Lapped to the west by the Tiber, the Municipio is also crossed by its tributary the Aniene, the second river of the capital, which runs alongside the areas of Monte Sacro, Sacco Pastore and Conca d'Oro.

Urban areas

Within the Municipio there are the urban areas of Cinquina, Porta di Roma, Vigne Nuove and the extra-urban area of Sant'Alessandro.

Historical subdivisions

The following toponymy areas of Rome are located within the Municipio:

- Quarters

- Q. XVI Monte Sacro and Q. XXVIII Monte Sacro Alto

- Zones

- Z. I Val Melaina, Z. II Castel Giubileo, Z. III Marcigliana, Z. IV Casal Boccone and Z. V Tor San Giovanni

Administrative subdivisions

The urban distribution of the territory includes the thirteen urban areas of the former Municipio Roma IV. Its population is distributed as follows.:[1]

| Municipio Roma III | |

| 4A Monte Sacro | 16,579 |

| 4B Val Melaina | 36,460 |

| 4C Monte Sacro Alto | 33,662 |

| 4D Fidene | 12,042 |

| 4E Serpentara | 31,997 |

| 4F Casal Boccone | 13,809 |

| 4G Conca d'Oro | 19,133 |

| 4H Sacco Pastore | 10,300 |

| 4I Tufello | 14,840 |

| 4L Aeroporto dell'Urbe | 2,060 |

| 4M Settebagni | 5,202 |

| 4N Bufalotta | 7,446 |

| 4O Tor San Giovanni | 899 |

| Not localized | 590 |

| Total | 205,019 |

Frazioni

The following frazioni of Rome lies within the area of the Municipio:

- Colle Salario, Settebagni, Villa Spada

Infrastructure and transport

Railways

The Municipio is currently connected by various urban bus lines, as well as by the Line B1 of the Rome Metro, a branch of Line B, which started its service on 13 June 2012,[3] whose terminus is the station Jonio.[4]

Streets

The Municipio III is crossed by three of the most important arteries of the capital:

- to the north, the Grande Raccordo Anulare, which crosses it from west to east for about 8 km, between the Ponte di Castel Giubileo and Via Nomentana; in particular, the exits "Castel Giubileo", "Salaria", "Via di Settebagni – Bel Poggio – Fidene", the "Diramazione Roma Nord" of the Autostrada A1 and "Via della Bufalotta – Via delle Vigne Nuove" are within the Municipio.

- to the west, Via Salaria runs parallel to the railway, crossing the Municipio from south to north, starting from Ponte Salario (on the river Aniene) up to Monterotondo Scalo, and touching Settebagni and the Urbe Airport.

- to the east, the Via Nomentana crosses Monte Sacro and Monte Sacro Alto, before reaching Fonte Nuova, Mentana and Monterotondo.

History

.jpg.webp)

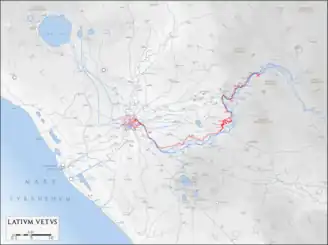

The history of the Municipio Roma III concerns the territory of the northern area of Rome, between the Tiber and the Aniene, delimited by three major road axes: the Via Salaria to the west, the Via Nomentana to the south-east and, in much more recent times, the Grande Raccordo Anulare to the north.

The first evidence of the presence of man in the aforementioned territory dates back to 700,000 years ago; in the antiquity there was a great demographic development with the constitution of several cities in the area, roughly in the years of the founding of Rome, such as Crustumerium, inhabited by the Crustumini, and Fidenae.

In the imperial age, on the contrary, there was a depopulation due to the proliferation of villae in the territory; the same phenomenon occurred in the Middle Ages with the casali (farmhouses).

It is in the 20th century that the area reached a great and rapid urban development, with the birth of the garden city of Monte Sacro and then, in the second post-war period, of many other neighborhoods.

Geology and prehistory

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, the territory was subject to volcanic phenomena, caused by the Monti Sabatini and the Alban volcanoes.

In prehistory the territory was already inhabited. In the area called Bufalotta, remains of human fossils dating back to 700,000 years ago have been found; other remains dating back to 200,000 years ago have been found in a place called Monte delle Gioie (in the quarter of Serpentara) and in Sacco Pastore (where today there is Via Val di Nievole). The latter are more recent findings, dating back to about 100,000 years ago,[5][6] were discovered between 1929 and 1935: a Neanderthalian skull was found for the first time in Italy near Sacco Pastore by the paleoanthropologists Alberto Carlo Blanc and Henri Breuil. The Man of Saccopastore takes his name from these discoveries.

From the ancient settlements to republican Rome

The most important ancient settlements in the territory were undoubtedly Custrumerium and Fidenae. The first one is also mentioned by Virgil in the Aeneid[7][8] and was conquered by Romulus, while the date of conquest of the second one is uncertain.

It is known that, when Rome was founded in 753 BC, Fidenae was a medium-large center that exploited the transport and communication routes both by river and land. For this reason, the Romans always tried to isolate it (especially from Veii) and to conquer it. According to traditional accounts, the conquest took place under the reign of Romulus, through the so-called battle of Fidenae.[9][10][11] A more accredited hypothesis traces the conquest back to 474 BC when – though the Fidenates tried to contrast the Romans through an alliance with the Etruscan city of Veii – the city was occupied by a Roman garrison to conquer it. The Romans sacked it and then set it on fire between 436 BC and 435 BC: the city then became a municipium of Rome and a part of the inhabitants was enslaved.[12]

To rebuild a part of the edifices burned by the Gallic fire, Rome drew a large quantity of blocks of tuff from the quarries near Fidenae.[13] Thanks to the fall of Fidenae, the Romans gained a good position in the fight against Veii. In the late Republican age, according to Strabo,[14] Fidenae, like Gabii and Labicum, was often taken as an example of a city subdued and reduced to a village.

Nowadays, as a testimony to the millennial history of the Municipio, it is possible to visit the protohistoric house of Fidenae, a full-scale reconstruction, made with ancient building techniques, of a house dating back to the end of the 9th century BC, which has been found almost intact.[15]

The secession of the plebs on Monte Sacro

The area of Monte Sacro takes its name from the hill of the same name, which is famous for a great revolt of the plebs that took place in 496 BC: the plebeians took refuge on the hill, in what, for many, was the first strike in history. The revolt was quelled by Senator Menenius Agrippa with the famous apologue pronounced in 503 BC:[16] Agrippa (as Aesop did) metaphorically compared the Roman social classes to a human body. Thanks to this convincing speech, the situation was brought back to order and the plebeians returned to their duties. However the plebs, having retired and ceased to make its contribution to public life, obtained the establishment of the Tribunes of the plebs and of the Aediles of the plebs, as well as the creation of its own assembly, the concilium plebis, which elected the Tribunes and the Aediles. To commemorate the event and the agreements made, an altar dedicated to Jupiter Terrificus was erected on the hill: for this reason it became "sacred".[17]

The imperial age

The villae

The area, during the Imperial age, reached a great development from a residential and socio-economic point of view, but to explain this phenomenon it is necessary to go back to the last two centuries of the Roman Republic: in fact, after the end of the wars that consecrated Rome as the absolute power in the Italian peninsula and in the Mediterranean Sea (4th–3rd century BC), the countryside had become depopulated because the farmers who managed it had been engaged in the wars themselves.[18] For this reason, at the beginning of the 2nd century BC, new forms of land ownership took shape, such as the villa, a medium-sized land possession worked by slaves under the control of a farmer (vilicus), in which the owner lived only occasionally. The villa was the most used system in the territories concerned. In fact, between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century AD the area around Monte Sacro had surely to be dotted with villae having productive functions: in addition to the many archaeological finds of fragments of amphorae and large food containers, artifacts dating back to the imperial age were found, which attest the presence of villae where fruit trees, wheat, flowers, vegetables, olive trees and vines were grown, in today's areas of Monte Sacro, Fidene, Colle Salario, Vigne Nuove, Bufalotta, Serpentara, Tor San Giovanni, Prati Fiscali, Settebagni, Castel Giubileo and Magliana.[6] We also know, from the sources which have been handed down to us, that oil and grapes were the main productions. In the territory of the Municipio there are hundreds of Roman villae; here below some of them will be discussed.

Among the most important villae there is that of the freedman Faonte.[19][20] The archaeological excavations also brought to light a funeral urn with an inscription dedicated to Claudia Eglogae:[21] this woman was the nurse of Nero and, together with Acte, collected the body of the Emperor and transported it to the tomb of the Domitii. About this villa, Suetonius informs us that this freedman offered to host Nero himself on the run from Galba and his men, ready to kill him. But, with the men of Galba a few meters away, the Emperor decided to commit suicide by stucking a dagger in his throat, with the help of Epaphroditus. Suetonius indicates the exact location of this building: it rose between Via Nomentana and Via Salaria and precisely, according to some archaeologists, in Via Passo del Turchino.[22] The villa was probably very large and was divided into two sections: a rustic one and a residential one. Near the villa there was a large cistern which is still visible.[23]

In the quarter of Colle Salario, near Via Serrapetrona and Via di Monte Giberto, there is a fenced area where there was another villa. Dating back to the end of the Republican age and the first phases of the Imperial age, the remains of the villa appear as a masonry core made of mortar and tuff. Furthermore, the presence of fragments of black-painted ceramic makes it almost certain that the site was already frequented in the 2nd century BC.[24]

In Via di Settebagni there is a hill which houses the remains of an Imperial age villa: in particular, there are large barrel-vault rooms. The presence of fragments of tiles and ceramic suggests that the construction of this villa dates back to the late Republican age. The hill where the remains rise was probably terraced by the Romans themselves.[25] Furthermore, the remains of a villa called Redicicoli del bene were also found near Settebagni: This site, damaged during the construction of a complex of townhouses, was probably inhabited until the 5th century AD. Two tombs have also been found nearby, but it is not clear whether these are connected in any way to the villa.[26]

In Via della Bufalotta there are also some remains, accessible by a dirt road, of a late-Republican villa. The excavations were carried out by the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma in 1984 and brought to light the remains of a rustic building together with two tanks used for the production of oil and wine, which are still visible today.[27]

In Piazza Monte Torrone there are other remains of a large villa dating back to the 2nd century AD, while the remains of another villa are still visible in Via della Marcigliana. Probably some rooms of the villa were used as cisterns.[28]

Other findings dating back to the Imperial age

In the quarter of Val Melaina there are the remains of an ancient Roman cistern. The cistern, dating back to the 1st century BC, came to light in 1981, during the urbanization works in the area, and is built in tuff. Nearby there are other ancient structures in opus reticulatum used for the pressing of the grapes. The discovery of abundant fragments of tiles and ollae suggests that the site was already inhabited in the archaic era and continued to be so until the Imperial age. A well dug in the tuff, on the hilltop of the Tallongo estate, can perhaps be associated to the remains of a villa from the same period.[29]

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages there was a great depopulation of the area which today corresponds to the Municipio IV, but the urban centers of Capobianco, Fidenae and Monte Sacro were not involved. An opposite situation occurred in Colle Salario (and therefore probably also in the contiguous areas of Castel Giubileo) and along the Via Nomentana, near the place of the martyrdom of St. Alexander, where there was a great demographic increase. The expansion of the inhabited territory mainly affected the areas close to the religious centers of St. Michael the Archangel, Castel Giubileo and St. Alexander, as well as the surroundings of other churches.

For many scholars, the phenomenon can be explained by the fact that, after the increasingly frequent barbarian invasions, the churches became a place of aggregation for the population, especially if working in agricultural activities. As a response to this growing phenomenon, attempts were made to establish small peasant associations formed by the farmers themselves: they were the so-called domuscultae, which had a great development under Pope Zachary (741–752) and Pope Adrian I (772–795) and helped to increase the properties of the church, which were gradually increasing in comparison with the private properties. Edifices built during the Imperial age and still in good condition were often reused for this purpose.[30] The establishment of these properties commences the phenomenon of the casali, the heirs of the Roman villae. Many casali were built on the remains of the villae in the areas of Marcigliana, Prati Fiscali and Serpentara, but monuments and tombs were reused as well.

There were several fortified casali, each of which was part of the homonymous titular estate: Casale di Redicicoli, Casal de' Pazzi, Casale della Cesarina, Casale di Castel Giubileo, Casale della Marcigliana, Casale della Cecchina, Casal Boccone, Casale di Villa Spada, Casale di Malpasso, Casale di Settebagni, Casale di Massa, Casal Fiscale and Casale di San Silvestro.[31]

In addition to the construction of the casali, other sites of ancient Rome were destined for various activities. An example is a Roman sepulcher of the 1st century BC located near Ponte Salario: in the Middle Ages it was used as a watchtower for defensive and surveillance purposes and in 537 the so-called Torre del Caricatore was built on it. The tower shows an alternation of light and dark stones in order to make it more visible. The towers built with this system were called vergatae. Other watchtowers were erected on Roman mausoleums, including Torre della Cecchina and Torre di Capobianco (also called Torre di Castiglione).

Between 1500 and 1700: the casali

The number of casali remained unchanged from the 17th until the 19th century. The casale was the core of the land properties and attached great economic importance to the farming. Nevertheless, from the ancient sources it is easy to deduce the presence of plots cultivated with vineyards near Ponte Salario and Tufello in the 14th century, in Castel Giubileo – where white wines were produced – between the mid-16th century and the 17th century, and near Casal Boccone and Casal de 'Pazzi in the 17th century. The present area of Vigne Nuove (Italian for "New Vineyards") takes its name from vineyards planted in the 18th century. It is also interesting to mention the origin of other place names: Redicicoli (where Via del Casale di Redicicoli now passes) takes its name from the word radiciola, meaning radicchio or chicory, while the name of Serpentara derives from the fact that in ancient times the area was infested with snakes (Italian: serpenti).[32]

Between 1878 and 1911 the lands were divided into plots according to a law for land reclamation: The current casali were built in that period, therefore adapted to the needs of the time.

Recent history: from the Garden city to the birth of the new quarters

In 1919, employees of the State Railways built the first houses in the area today known as Monte Sacro:[33] they rose along Via Nomentana in the direction of Prati Fiscali. The Governor of Rome, Filippo Cremonesi, and the President of the Istituto Case Popolari, Alberto Calza Bini, promoted a plan concerning the construction of a Garden city[34] in the area of Monte Sacro: it should have been the largest in Italy and in the world. The construction, based on a project by Gustavo Giovannoni, was entrusted to an association called Consorzio Città Giardino Aniene, formed by the Istituto Case Popolari and the Unione Edilizia Nazionale. According to the project, some essential services for the development of the Garden city would have arisen near Ponte Tazio: the park, the post office, the cinema-theater, the shops and the church. Tree-lined streets should have been traced around these buildings and houses (mainly single-family) should have been surrounded by green areas and gardens.[35]

The quarters of Val Melaina, Cecchina and Tufello were created in the territory of the Municipio IV between the 1930s and 1940s; later the Grande Raccordo Anulare was built. The first houses that were built in the quarter Tufello were very similar to the ones built years earlier as the core of the garden city of Monte Sacro (low-rise buildings surrounded by greenery). But, after World War II, to stop the rampant growth of unemployment, the State decided to intervene with plans that would allow the development of housing activities in the area. This program involved building development with a policy of tax advantages for the construction companies and the abolition of taxes on the building sites; its aim was the construction of new popular neighborhoods in the peripheral areas, by demolishing the numerous shacks rising on the major communication arteries of Rome (such as Via Salaria and Via Nomentana). For this reason, the building became more and more intensive: the townhouses became much higher and the green areas were reduced to a minimum.

Between the 1950s and the 1970s the phenomenon totally degenerated due to the further reduction of the available spaces: the buildings reached heights up to 7 floors and had very small areas for gardens and courtyards. This trend involved the Garden city itself (many single-family dwellings were demolished and replaced with much higher buildings), as well as Tufello, Bufalotta and Vigne Nuove.[36] Between 1959 and 1962 the quarter of Monte Sacro Alto (also called Talenti) was created, in the area between Via Nomentana and Via della Bufalotta. Even the ancient Fidenae was affected by the post-war building phenomenon, in spite of an ordinance dating back to 1962 which provided for an exclusively agricultural use: therefore a new urban zone called Fidene was created between the 1960s and the 1970s. Neighboring areas, such as Castel Giubileo, were built in the same years, while, after 1962, the growth of the quarter Vigne Nuove received new impetus with the construction of public housing promoted by the Istituto Autonomo Case Popolari.

After 1970, what was then called "IV Circoscrizione" experienced a great building growth not only along Via delle Vigne Nuove, but also in other areas such as Conca d'Oro, Val Melaina, Nuovo Salario and Serpentara.[37]

Subsequently, between 1980 and 1985, buildings of medium height (many of them reaching six floors) and tall towers (up to fifteen floors) were built in the area now called Colle Salario. The phenomenon of urbanization did not stop even in the quarter Talenti: in the years between 1995 and 1998 the building plans involved the large green extensions between Via Gaspara Stampa, Via Nomentana and Via di Casal Boccone.[38]

Finally, after 2005, the groundwork was laid for the construction of the new residential district of Casale Nei. This quarter, partly still under construction and enclosed between Colle Salario and Vigne Nuove, is growing around a large green area: Parco delle Sabine.

It should be noted, in conclusion, that in recent years a greater ecological awareness has slowed down urban development and allowed to preserve numerous green areas in the Municipio.

Chronology

- 700,000 years ago: the first fossils date back to this period.

- 200.000/100.000 years ago: the Man of Saccopastore lived in these territories.

- 474 BC: Fidenae is conquered by Romans.

- 436 BC-435 BC: The Romans set fire to Fidenae.

- Imperial age: the area has a great urban development.

- 68: Nero dies before refusing to be hosted by Faonte.

- 2nd century BC-2nd century AD: the villae have a huge development in the area.

- 537: The Torre del Caricatore is built.

- 740–780: another grea urban development in the area.

- 17th century-19th century: rise of the casali.

- 1919: the first houses are built in Monte Sacro.

- 1920s–1940s: the Garden city is built.

- 1930s–1940s: the quarters Val Melaina and Tufello are built.

- 1950s–1970s: very tall edifices are built, the Garden city is partially demolished.

- 1970s: the quarters of Conca d'Oro, Serpentara and Nuovo Salario are built.

- 1980–1985: the quarter Colle Salario is built.

- 1994: opening of the FR1 regional railway line.

- 1995–1998: the construction of the quarters Talenti and Casal Boccone does not stop.

- 2005: the new quarter Porta di Roma is built.

- Construction of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' Rome Italy Temple began in 2010, and the temple opened after its dedication in 2019.[39]

- 2012: opening of three stops of the Line B1 of Rome Metro.

Culture

Libraries

- Ennio Flaiano, in Via Monte Ruggero

Cinemas

- Cinema Antares, in Viale Adriatico

- Uci Cinemas Porta di Roma, in Via delle Vigne Nuove, within the Porta di Roma shopping center.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Roma Capitale – Roma Statistica. Population inscribed in the resident register at 31 December 2016 by toponymy subdivision.

- ↑ After Municipio Roma XV (former Municipio Roma XX – Cassia Flaminia), Municipio Roma IX (former Municipio Roma XII – EUR), Municipio Roma X (former Municipio Roma XIII – Ostia), Municipio Roma XIV (former Municipio Roma XIX – Monte Mario) and Municipio Roma VI (former Municipio Roma VIII – Roma delle Torri), all with an area greater than 100.00 km2.

- ↑ Line B1 from ATAC website.

- ↑ Description of the line on Roma Metropolitane website.

- ↑ Storia di Val Melaina Archived 23 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Storia del IV Municipio Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Publius Vergilius Maro, Aeneid, VII, 629–631

- ↑ Crustumerio

- ↑ Livy, Ab Urbe condita libri, I, 14

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Romulus, 23, 6–7.

- ↑ Fidenae under attack

- ↑ Livy, Ab Urbe condita libri, Book IV, 2, 17–20.

- ↑

- ↑ Strabo, Geographica, V, 2, 9

- ↑ "Casa protostorica di Fidene". Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Livy, Ab Urbe condita libri, II, 32.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, VI. 90

- ↑ Villae in Rome: introduction

- ↑ Villa di Faonte

- ↑ Villa di Faonte 2

- ↑ Claudia Eglogae and Nero

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Nero, 48–49.

- ↑ Villa of Faonte: cistern and basement

- ↑ Villa di Via Serrapetrona from Romamontesacro.it website

- ↑ Villa in via di Settebagni from Romamontesacro.it website.

- ↑ Villa Redicicoli del Bene Settebagni from Romamontesacro.it website.

- ↑ Villa di via della Bufalotta from Romamontesacro.it website.

- ↑ Villa di via della Marcigliana from Romamontesacro.it website.

- ↑ Cisterna Nuovo Salario from Romamontesacro.it website.

- ↑ The popes and the territory in the Middle Ages

- ↑ Medieval casali

- ↑ The name Serpentara

- ↑ Montesacro città giardino Archived 23 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Garden city is an urban model of English origin, whose aim is to make citizens live the benefits of a life both in the city and in the countryside, eliminating the respective inconveniences.

- ↑ Città giardino Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Quarters 1970s Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Quartieri anni 70 2 Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Talenti Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Rome Italy Temple to Begin Public Tours, published 14 January 2019, accessed 29 June 2022

Bibliography

- Giovanni Sozi (1994). Montesacro. Antico e nuovo. Rome: Litotipografia Litodama.

- Ludovico Gatto (1995). L'Italia nel Medioevo: gli italiani e le loro città. Rome: Newton Compton. ISBN 978-88-8183-182-1.

- Stefania Quilici Gigli (1986). Roma fuori le mura. Rome: Newton Compton.

- Armando Ravaglioli (1997). Roma anno 2750 ab urbe condita. Roma: Newton Compton. ISBN 978-88-8183-670-3.

- Comune di Roma (1996). La città giardino. Una passeggiata nel territorio della IV circoscrizione. Rome.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - IV Circoscrizione (1999). Le origini. Un museo per la Quarta Circoscrizione. Rome.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lorenzo Quilici; Stefania Gigli Quilici (1980). Crustumerium. Rome: ISCIMA.

- Laurent Keller (1991). La civiltà etrusca. Milan: Garzanti.

- Richard Bloch (1994). La civiltà etrusca. Milan: Xenia.

- Massimo Pallottino (1982). Etruscologia. Milan: Hoepli.

- Mario Torelli (1981). Storia degli etruschi. Rome-Bari: Laterza.

- Guido Clemente (1990). Guida alla storia romana. Milan: Mondadori. ISBN 978-88-04-33871-0.

- Filippo Coarelli (1980). Roma. Rome-Bari: Laterza.

- Filippo Coarelli (1993). Dintorni di Roma. Bari: Laterza.

External links

- "Storia Municipio IV". Portali di Roma. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- "Amministrative 2016 – Municipio 03 (già 04)". Roma Capitale.