Munio Gitai Weinraub | |

|---|---|

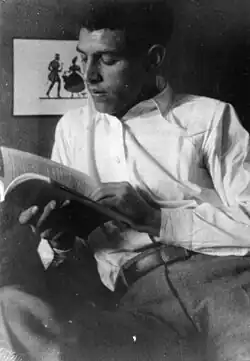

Munio Gitai Weinraub, Bauhaus, 1930 | |

| Born | March 6, 1909 Szumlany, Schlesien |

| Died | September 24, 1970 Haifa, Israel |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Years active | 1932-1970 |

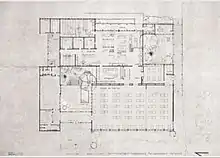

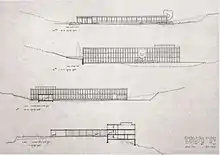

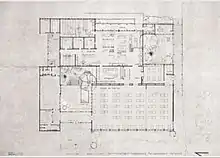

| Known for | Planning of administration and library building of Yad Vashem-The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Munio Weinraub, 1953-1955. The Hydraulic Institute, Technion, Haifa, Munio Weinraub et Al Mansfeld, 1953-1956. Meiser Institute for Jewish Studies, Givat-Ram Campus, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Munio Weinraub et Al Mansfeld, 1955-1957. "Lighthouse for the Blind", Kiryat Haim, Munio Weinraub et Al Mansfeld, 1956-1958. Kiryat Hamemshala, government complex in Jerusalem. |

| Spouse(s) | Efratia Munchik Margalit, marriage 1936 |

| Children | Gideon Gitai (1940-2019), Amos Gitai |

Munio Gitai Weinraub (March 6, 1909 – September 24, 1970) was an Israeli architect, a pioneer of modern architecture and urban and environmental planning in Israel, and one of the most prominent representatives of the Bauhaus heritage in the country. Throughout his 36 years career, Weinraub was responsible for the construction and planning of thousands of housing units, workers' housing units and private homes in and around Haifa. Weinraub took part in the initial planning of the Hebrew University campus in Givat Ram and the Yad Vashem Museum in Jerusalem. From the beginning of his career, Weinraub sought to combine the values of Hannes Meyer's social planning with the meticulous construction art of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. His works are designed out of deep social sensitivity and are characterized by minimalist geometry, simple and modest presence and efficient functional planning. Inspired by his teacher Mies van der Rohe, Weinraub chose to give up "problems of form" in order to dedicate himself to "problems of construction" and focus on the act of construction itself, the treatment of the material and the processing of the architectural individual.

Biography

Munio Gitai Weinraub was born in the small town of Szumlany in Galicia and grew up in the city of Bielsko, in Silesia - German-speaking region of Poland. His father was a farm manager in the service of Polish landlords and his mother came from a wealthier background of small industrialists. He was the youngest of four sons and his childhood was overshadowed by many hardships during World War I. After the war he became a member of the Jewish youth group Hashomer Hatza’ir, a scouting organization that combined nature explorations similar to those of Baden Powell's Boy Scouts in Great Britain, and the romantic tendencies of the German Wandervögel groups, with the study of Zionist and Socialist ideologies.

In 1936 he married Efratia Margalit (Munchik) (1909–2004). The couple had two sons, photographer Gideon Gitai (1940-2019) and Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai, who himself studied architecture at the Technion in Haifa and University of California, Berkeley.

At the age of eighteen, in 1927, when Weinraub applied for architecture studies at the Bauhaus School in Dessau, it was suggested to him to be first enrolled in the art school Tischlerschule in Berlin, where he studied drawing, perspective, traditional furniture design and more, and gained a deep understanding of the woodwork and carpentry. In 1930, he enrolled in Bauhaus. Weinraub's desire to study at Bauhaus is in line with the political activism of his youth group, as the Bauhaus had the reputation of being the most artistically and politically progressive design school in Europe at the time. Walter Gropius, who founded the Bauhaus in 1919 as an anti-academic school of the Arts & Crafts type, succeeded in expressing the collaborative spirit of the younger generation, who sought to break free from the barren social and political approaches that led to World War I. "Cathedral of Socialism" is a fitting metaphor for the description of the early Bauhaus, which was devoted to designing a new society. The school was built on the myth of the Guilds in the Middle Ages and the design project was caught up in the spirit of the shared ethos. The Bauhaus was an obvious choice for idealist students with leftist tendencies, such as Weinraub.

After his studies, Weinraub worked for Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Bauhaus director at the time. Mies hired him to work with him in his Berlin office, where his main mission under was to supervise the installation of a number of works at the 1931 German Building Exhibition.

With the rise of Nazism and the closure of the Bauhaus by Goebbels in 1933, Weinraub was arrested, beaten and jailed on the ridiculous pretext of “treason against the German people”. He was then expelled and managed to find refuge in Switzerland, where he worked for the architect Moser in Zurich. At the end of 1934, he left Europe and immigrated to Palestine and settled in Haifa, which was the urban base of the Hebrew labor movement. He maintained close ties with Kibbutz Hashomer Hatzair when he took part in the planning and design of sixteen of the movement's founding points. The leadership roles he played in the movement as a teenager instilled in him a sense of solidarity with such cooperative societies..

From 1937 to 1959, he worked in partnership with architect Al Mansfeld, with whom he founded the Munio Weinraub et Al Mansfeld architects office. Their work focused on serving local labor movement institutions and designing schools, cultural structures, factories, employee housing, kibbutzim, private residences, office buildings and industrial facilities. The salient features of their joint work in its first decade were the reduction of the status of pre-given compositional patterns and a preference for pragmatic solutions.

In 1949 Weinraub was nominated as the head of the Department of Architecture in the planning office at the Ministry of Labor and Housing, directed by Arieh Sharon. He was therefore involved in the initial planning policy-making of Israel.

In 1951 Weinraub-Mansfeld collaboration won the entry for the site planning of the government center Ha-Kirya, in Jerusalem. In addition to this honorable mention, the firm won a dozen more national competitions during the 1950s.

Weinraub and Mansfeld both began teaching at the Technion, in Haifa at that time. Their academic roles, combined with the challenge of entering numerous architectural competitions, influenced their diverging theoretical conceptions and their collaboration ended in 1959. When Weinraub and Mansfeld dissolved their partnership, it was one of the leading firms in Israel, regularly published in Bauen und Wohnen, L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, and other international publications.

Weinraub continued his distinguished career on his own, pursuing commissions for socially conscious architecture, working for the labor federation, the kibbutzim, and various educational institutions. One of his final projects was the water tower at Gil Am (a youth rehabilitation institution in Shefar'am). This project perhaps best embodies his lifetime commitment to create useful works, designed with precise details and expert knowledge of materials to achieve a serene, minimalist aesthetic.

In 35 years of career, Weinraub has established a substantial body of work of some 300 projects, consistently applying the Bauhaus principles and developing them. He left behind a number of masterpieces, such as the Hydraulic Institute of the Technion in Haifa.

He died in Haifa in 1970 at the age of 61, buried in Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk.

Architectural work

Munio Gitai Weinraub was an architect of exceptional merit. Of the few Israeli architects who attended the Bauhaus, he alone put into practice the Bauhaus ideals of designing things according to the way they were to be produced. His work was deceptively simple, meticulously detailed, well-proportioned, sensibly planned, and respectful of the environment. He sought to bring to the Jewish settlements in Palestine a transcendent modern architecture that would resist ideological frames and operate neutrally to serve basic human needs through elegance, progressive technology, and infrastructural foresight. Weinraub was a Functionalist in the best sense of the term. Inspired by his teacher Mies van der Rohe, he denunciated problems of shape in favor of problem of construction and had a deep understanding of the architectural detail in the overall set of construction. Architecture was for him a useful art and a service. Behind all of his projects was a special concern not only for the lives of a building's future occupants, but for the collective environment as well.

As he made sure to pay attention to the modes of production, Gitai-Weinraub invested energy in the tectonic aspects of design and brilliantly solved specific questions of how elements were to be joined and materials were to be finished, so that the building process could be executed properly. His buildings were composed of simple, well-proportioned volumes that are harmonious with their environments but rarely ostentatious in visual or spatial terms. His was a polite architecture that fit in rather than stuck out. This deferential attitude was consistent with the theories of the Neu Sachlichkeit (new objectivity), a strain of unsentimental Functionalism that was prominent during the years of the architect's training in Germany.

Weinraub's strengths as a designer perhaps help to explain his relative lack of notoriety in recent times. Never flashy, pompous, or individualistic, his works have remained virtually invisible to a culture in search of eccentric authors. As a result, some of his finest buildings have been mercilessly defaced, remodeled, or demolished without the slightest consideration that they were indeed the products of a very talented author. Although he was not overly concerned with architectural theory, his buildings display a coherent typological rigor, which indicates a theoretical search for a humane Functionalism. The creative act in Weinraub's practice was based more on solving the problems of building and dwelling than on striving for stylistic originality. Considering the glaring incongruences that characterize the current urban environment in Israel as well as in any Westernized nation, Gitai Weinraub's sense of deference serves as a profound lesson. The sort of Functionalism he practiced was predicted on the rejection of individualism and image-consciousness in order to establish respect for how things are made, how things fit together and how space is used, from his earliest works. Such as they tiny cubicle houses in the workers’ suburbs of Haifa, to the grander projects of the 1950s, such as the Meiser Institute of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Gitai Weinraub's buildings have a harmonious sense of integration of materials, structure, and spatial organization that conveys the quality of security and wholeness.

Weinraub, in his love of the craft of building, was one of the few practicing architects in Palestine who truly worked according to the Bauhaus method. Gitai-Weinraub's work can be described as typical of his generation's spirit, but a close examination of his buildings reveals that the great attention he devoted to the details also distinguished them in this context. Apart from his activities as a designer and architect, Gitai-Weinraub (like many architects of his generation) was also a furniture designer who created desk and chair designs for some large companies.

His entire work - from the particular design of furniture to the construction of large-scale cities - is characterized by a firm commitment to the process: the making process, and the residential and use process.

Prominent projects

Many of the most interesting commissions Weinraub received were tied to the Histadrut's initiatives to promote Hebrew labor. He designed some of the industrial buildings of two prominent factories in the field of construction: the Phoenicia glass factory and the Vulcan iron and metal industries, both located in the estuary of the Kishon River in the Haifa Bay area. These factories were among the first on such a scale to be built in Palestine, and they played a significant role in changing the economic base of the region. For Phoenicia he built a vast, clear-span, metal-ribbed structure with a pitched roof, and capped with pushed-up monitor clerestories for light and ventilation. However, the large production resembled a column-free basilica, and was one of the largest (if not the largest) spaces built in Palestine at the time. In 1941 the Phoenicia Glass factory was the first of the large building industries in Haifa to be purchased by Solel Boneh, a Histadrut-controlled company, followed by the Vulcan Metal Works, whose sheds and furnaces were designed by Weinraub in the same year.

Weinraub planned two more factories that enabled the establishment of Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk, which sits halfway between Haifa and Acre: the Na’aman Brick and Tile Factory (1939–50) and the Askar Paint and Plaster Company (1938-1940). Two other projects were the design of the "Lighthouse for the Blind", an educational institution in Kiryat Haim, and the new dining hall of Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk. Weinraub and Mansfeld had many projects for the Histadrut institutions and its members, those that have been built and those that have remained on paper, including about 8,000 housing units for workers' subsidiaries such as Shikun-Ovdim and Solel-Boneh. The most prominent of these projects, apart from the Beit Hapoalim compound in Hadar, was the warehouse and office building of Hamashbir HaMarkasi, the cooperative that marketed the produce of all the collectives in the Hebrew community.

Apart from their impressive amount of projects in housing, so vital in the young country, and the advancement of industrial planning in the country, Weinraub and Mansfeld were also involved in three major projects concerning the design of national identity. The first was the design of the Yad Vashem Monument for Holocaust victims, the second was a construction plan for the government complex in Jerusalem, and the third was the building design of the Meiser Institute (now Feldman), one of the main buildings on the new campus of the Hebrew University of Givat Ram, which played a significant role in the establishment of a national culture.

The Munio Gitai Weinraub Museum of Architecture

In 2014, the Munio Gitai Weinraub Architecture Museum opened in Haifa, dedicated to Weinraub's private collection and in honor of Israeli architecture.[1] The museum was established by his son, Amos Gitai, and includes Weinraub's private archive and a room restoring the studio where he worked. The museum was established in collaboration with the Haifa Municipality and the Haifa Museums Company. The "Kowalski Efrat" office of the architects Zvi Efrat and Meira Kowalski was responsible for adapting the building to its purpose as a museum and Carmit Hernick Saar was responsible for its execution.

The museum's opening exhibition was 'The Architecture of Memory', curated by Amos Gitai. The exhibition was accompanied by the book "Carmel", in collaboration with the Munio Gitai Weinraub Architecture Museum and the Haifa Museums.

Every year, the museum hosts several exhibitions on Israeli and international architecture, and various events such as conferences and public conversations with architects and artists. The exhibitions in the museum are partly thematic and partly mono-graphic, and their purpose is to create discussions and raise questions concerning architecture that are at the center of public interest in Israel.

Among the exhibitions held at the museum:

- Building of the Khan al-Ahmar Bedouin School, Curators: Amos Gitai, Sharon Yavo Ayalon and Nitzan Satt, 2016.

- Public Housing, Curators: Sharon Yavo Ayalon and Nitzan Satt, 2016

- Ecological Ripples, Curator: Architect Dr. Joseph Cory, 2015.

- Industrial Urbanism: Places of production, Curator:Tali Hatuka, 2015

- Learning from Vernacular, For a New Vernacular Architecture, Curator: Pierre Frey, 2013

- Haifa Encounters : Arab-Jewish Architectural Collaboration during the British Mandate, Curators: Walid Karkabi and Adi Roitenberg, 2014.

- The Architecture of Memory, Curator: Amos Gitai, The Museum's Opening Exhibition, 2014.

In 2013, the film "A Lullaby for My Father" directed by Amos Gitai was released.

References

External links

- The Munio Weinraub Architecture Museum website. Israeli and international architecture, the relationship between Munio Weinraub and his son Amos Gitai, events. Opened in 2012 in Weinraub's former studio.

- Mies van der Rohe letter to Munio, August 1931

- Architecture and Film: Munio Weinraub and Amos Gitai, by Jane Czyzselska, Blueprint Magazine, 20 Aug. 2009

- Munio Weinraub and Amos Gitai, at artinfo.com

- Architecture of Israel

Bibliography

- Richard Ingersoll, Munio Gitai Weinraub: Bauhaus architect in Eretz Israel (photographs by Gabriele Basilico), Millan: Electa, 1994. (published in conjunction with the exhibition at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem ’Munio Gitai Weintraub : building for a working society’, 17 May-31 October 1994.)

- Olivier Cinqualbre, Lionel Richard, Munio Weinraub Gitai: Szumlany, Dessau, Haïfa: parcours d'un architecte moderne, Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2001.

- Town planning in Israel: New Towns for a New State, Building Digest, 10:11, November 1950.

- Israël centre de culture à Kiryat Haim, près de Haifa, Technique & Architecture, 10:1-2, pp. 94–95, 1951.

- Ha-Kirya: Der Regierungssitz Israels Architekten Munio Weinraub und Al Mansfeld, Plan: Revue suisse d'unrbanisme, 9:3, p. 92, May–June 1952.

- Immeubles à Haifa, Israël, L'Architecture d'aujourd'hui, 25:57, p. 96, 1954