The Mutual Burlesque Association, also called the Mutual Wheel or the MBA, was an American burlesque circuit active from 1922 until 1931. Controlled by Isidore Herk, it quickly replaced its parent company and competitor, the Columbia Amusement Company, as the preeminent burlesque circuit during the Roaring Twenties. Comedians Bud Abbott, Lou Costello (not yet a team), Harry Steppe, Joe Penner, Billy Gilbert, Rags Ragland, and Billy Hagan, as well as stripteasers Ann Corio, Hinda Wausau, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Carrie Finnell, performed in Mutual shows.[1][2] Mae West appeared in Mutual shows from 1922 to 1925.[3] Mutual collapsed during the Great Depression.

Formation

David Krause (a theater owner), Dr. George E. Lothrop (a physician who operated Boston's Howard Athenaeum), and Al Singer (who mounted shows on the Columbia wheel) incorporated the MBA in 1922.[4] Most of the franchisees and producers came from the American Wheel, a subsidiary of the Columbia circuit that played less prestigious venues and went bankrupt.[5] Isidore Herk, who had been president of the American Wheel, left to establish a vaudeville circuit with the Shubert organization. When that failed, Herk returned to burlesque the following year, replaced Singer, and eventually became Mutual's president. Mutual producers included Hurtig and Seamon, Al Reeves, Ed Rush, Ed Daley, John G. Jermon and Billy (Beef Trust) Watson.[6]

Many performers and producers abandoned Columbia, which was seen as behind the times, for the new wheel, which took inspiration from fast-paced and sometimes risque Broadway revues like Earl Carroll's Vanities and the Ziegfeld Follies. Yet it was a 1925 Columbia show, "Powder Puff Revue," that was the first burlesque show to follow the precedent set by Ziegfeld and Carroll and feature female nudity in static tableaux.

In Herk's obituary, Variety recounted, "With the initial season of the MBA, Herk learned that burlesque fans still wanted rough shows. So he obliged with plenty of bumps and strip-teasing, naughty blackouts and stag jokes. Although Herk had placed a limit on the 'dirt' stuff, producers and comics went beyond it when on the road. Everybody made plenty of coin."[7] Billboard claimed that Mutual "polluted public morals", but Herk defended it as the "jazz of American entertainment,"[8] and asserted that his shows were "clean, working class entertainments".[9]

Mutual thrived for most of the 1920s. At its peak, up to 50 self-contained Mutual shows rotated through as many affiliated theaters each season. (A season ran from Labor Day to the following April or May.) Ann Corio recalled in her 1968 book, This Was Burlesque, "Most people may imagine a burlesque company to consist of only a few strippers, a couple of comics and a straight man; but in the days of the Mutual Wheel, a burlesque company was as big—or bigger—than most touring Broadway musicals of today. This was a typical company of the day: a striptease star, a prima donna, a soubrette, a talking woman, a boy and girl dance team, two comics, a straight man, a singing juvenile, twelve or fourteen chorus girls, a musical conductor, three stage hands, and an assortment of cats, dogs, monkeys etc. (the actors' pets). In other words, a minimum of 26 people — plus all of the [wardrobe], scenery and props."[10]

With Mutual as legitimate competition, a bitter rivalry developed between Herk and his former boss, Sam Scribner, and Mutual and Columbia. But early in 1928, the two circuits were each losing customers to racier local stock burlesque shows like those of the Minskys.[11] Columbia and Mutual merged to form the United Burlesque Association, but the new circuit was still referred to as Mutual, with Herk in charge.

Affiliated Theaters

Mutual shows rotated through the following theaters during the 1927-28 season (alphabetically by city): Grand, Akron; Gayety, Baltimore; Howard, Boston; Gayety, Brooklyn; Star, Brooklyn; Garden, Buffalo; Empress, Chicago; Empress, Cincinnati; Empire, Cleveland; Lyric, Dayton; Garrick, Des Moines; Cadillac, Detroit; Mutual, Indianapolis; Gayety, Kansas City; Gayety, Louisville; Gayety, Milwaukee; Gayety, Minneapolis; Gayety, Montreal; Lyric, Newark; Hurtig and Seamon's 125th Street, New York; Gayety, Omaha; Orpheum, Paterson; Trocadero, Philadelphia; Academy, Pittsburgh; Corinthian, Rochester; Garrick, St. Louis; Gayety, Scranton; State, Springfield; Empire, Toledo; Hudson, Union City; Strand, Washington, D.C.; Gayety, Wilkes-Barre; and Plaza, Worcester.[12] Shows were not routed around the wheel in this order, and the list was subject to slight change each year. Some of these venues had previously been associated with the Columbia Wheel. Almost all have been demolished.

Show Titles

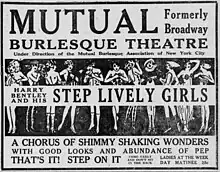

Mutual's shows for the 1927-28 season included Band Box Revue, Banner Burlesquers, Bathing Beauties, Big Revue, Bowery Burlesquers, Carrie Finnell's Show, Follies of Pleasure, French Models, Frivolities of 1928, Ginger Girls, Girls from Happyland, Girls from the Follies, Girls of the U.S.A., Happy Hours, Hello Paree, High Flyers, High Life, Hollywood Scandals, Kandy Kids, Jazztime Revue, Laffin' Thru, Moonlight Maids, Naughty Nifties, Nite Hawks, Nite Life in Paris, Parisian Flappers, Pretty Babies, Record Breakers, Red Hot, Social Maids, Speed Girls, Step Lively Girls, Stolen Sweets, Sugar Babies, and Tempters.[13] Some titles were used year after year, although with different casts and content. (Sugar Babies was used as the title of an unrelated burlesque musical produced on Broadway in 1979.)

Decline

After the 1929 stock market crash, Mutual began a precipitous decline as its working-class audience became and remained unemployed and the number of stock (local independent) burlesque theaters multiplied. Herk cut salaries, budgets and casts, but many shows did not complete their routes in 1930 and 1931. In the spring of 1931, Herk pared the circuit down to 10 shows in as many weeks and theaters. This strategy was not successful in keeping Mutual afloat, and on June 9, 1931, Variety declared, "Mutual Officially Dead." Herk joined forces with the Minskys and organized a new wheel of 25 shows and theaters called the New Columbia Burlesque Circuit, but it, too, eventually crumbled. Large, organized wheel burlesque was replaced by stock burlesque, some with smaller, localized circuits.

References

- ↑ Furmanek, Bob, and Ron Palumbo. "Abbott and Costello in Hollywood." Perigee, 1991. ISBN 0-399-51605-0

- ↑ Zeidman, Irving. "The American Burlesque Show." Hawthorn Books, 1967.

- ↑ Shteir, Rachel. "Striptease : The Untold History of the Girlie Show." Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802935-9.

- ↑ Zeidman

- ↑ Zeidman

- ↑ Zeidman

- ↑ Variety. "Burlesque loses vet showman as Izzy Herk dies in N.Y. at 61." July 12, 1944.

- ↑ Shteir.

- ↑ Stewart, Donald Travis (2014). "Barons of Burlesque: Isidore H. 'Izzie' Herk". Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- ↑ Corio, Ann and Joseph DiMona. "This Was Burlesque." Open Road Media, 2014.

- ↑ Green, Abel and Joe Laurie. "Show Biz: From Vaude to Video." Henry Holt and Co., 1951.

- ↑ "Burlesque Routes."Variety, Dec. 28, 1927. p. 53.

- ↑ "Burlesque Routes."Variety, Dec. 28, 1927. p. 53.