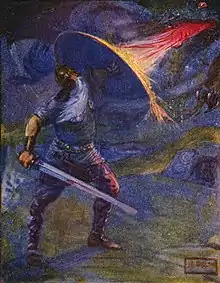

Næġling (Old English: [ˈnæjliŋɡ]) is the name of one of the swords used by Beowulf in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem of Beowulf. The name derives from "næġl", or "nail", and may correspond to Nagelring, a sword from the Vilkina saga. It is possibly the sword of Hrethel, which Hygelac gave to Beowulf (ll. 2190-94).[1][2] Næġling is referenced many times as a fine weapon—it is "sharp", "gleaming", "bright", "mighty", "strong", and has a venerable history as an "excellent ancient sword", "ancient heirloom", and "old and grey-coloured".[3] However, the sword does not survive Beowulf's final encounter with the dragon, snapping in two—not because of the dragon's strength, but because of the hero's strength:[4]

Næġling forbærst,

ġesƿác æt sæcce sƿeord Bíoƿulfes,

gomol ond grǽgmǽl. Him þæt ġifeðe ne ƿæs

þæt him írenna eċġe mihton

helpan æt hilde; ƿæs sío hond tó strong

Beowulf's hand is "too strong" for the weapon. Stopford Brooke claims this is "absurd, for Beowulf had fought with it all his life", and that "some later editor" inserted the passage, conflating Beowulf with a story told of Offa of Mercia.[4] While Taylor Culbert argues the poet blames the weapon for it, effectively "aggrandiz[ing] Beowulf in the eyes of the reader",[3] Judy Anne White, in a Jungian reading of the poem, proposes that "Beowulf's inability to use a sword is a part of his destiny, a question of fate, and therefore beyond his control."[5]

The idea of a sword failing for the hero at a crucial time has parallels in other Germanic works such as in the Volsunga saga and Gesta Danorum. However this is especially true in the Gunnlaugs saga, where the author goes at pains to show that it was the hero and not the foe who broke the sword.[6] Furthermore, in Germanic tradition, exceptional swords may often use words such as old, ancient, or ancestral. However this may not always fit the story of the hero, such as when the sword is forged for him. In Næġling's case, the sword has more of a literary characteristic than a specific ancestral lineage, as is evident from its name. Nevertheless, the sword is described as being gomol ond grægmæl (old and gray).[7]

See also

- Hrunting, another sword used by Beowulf

Notes

- ↑ Mullally, Erin (2005). "Hrethel's Heirloom: Kinship, Succession, and Weaponry in Beowulf". In Yvonne Bruce (ed.). Images of Matter: Essays on British Literature of the Middle Ages and Renaissance: Proceedings of the Eighth Citadel Conference on Literature, Charleston, South Carolina, 2002. University of Delaware Press. pp. 228–242. ISBN 978-0874138948. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Klaeber, Friedrich; Fulk, Robert Dennis; Bjork, Robert E.; John D. Niles (2008). Klaeber's Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburg. University of Toronto Press. pp. 254, 471. ISBN 978-0802095671. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 Culbert, Taylor (1960). "The Narrative Functions of Beowulf's Swords". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 59 (1): 13–20. JSTOR 27707401.

- 1 2 Brooke, Stopford A. (1892). The history of early English literature. New York: Macmillan. pp. 54 n.1.

- ↑ White, Judy Anne (2004). Hero-Ego in Search of Self: A Jungian Reading of Beowulf. Peter Lang. pp. 105–6. ISBN 978-0820431154.

- ↑ Garbáty, Thomas Jay (1962). The Fallible Sword: Inception of a Motif. The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. p. 58-9

- ↑ Portnoy, Phyllis (February 1, 2006). The Remnant: Essays on a Theme in Old English Verse. Runetree. p. 25. ISBN 978-1898577102.