The Nantucket forests have an unusual history. Continual salt saturated wind and nutrient poor soils set severe limits upon tree growth and the wood products that might be accessed by both indigenous peoples and colonial settlers.

Short trees and short timbers

Nantucket Island lies 30 miles off the southern coastline of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. In 1775, Nantucket was the largest whaling port in the world, and the third largest port in Massachusetts. However, dominance in this most adventurous, dangerous and potentially lucrative of all maritime trades were not supported by an extensive, local, ship building industry. Early Nantucket forests were unusual and determined the scope of indigenous and colonial wooden ship building on Nantucket Island.

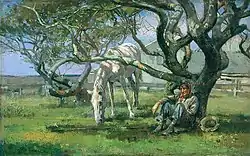

In spite of numerous statements about island forests as a source for lumber (see 1889 USGS report which only repeats local oral tradition), a strong case can be made that Nantucket has not been forested for the past 4,000 years at least in terms of what is usually thought of as a forest - numerous tall trees 50 or more feet in height. Visitors to Nantucket in the late 18th and early 19th centuries describe the island as nearly treeless.[1] However, many publications mention post glacial forests composed of oak, with some beech, pine, maple, and hickory. These trees were present but only in small numbers and severely reduced in height. They were cut down for firewood, fence posts and short building timbers in the decades following settlement in 1659. Speculation that after the island trees were cut down, a rich soil was washed away by erosion cannot be confirmed. Nantucket has many small dry' valleys without outlets to the sea, and rich loam soil cannot be found in these localities. Old forests have not existed for the past 2,000 years or more, deep rich leaf mold is absent and adequate soil depth to provide root anchorage for large trees is not present.[2] This photograph of a contemporary Nantucket moor depicts a landscape with few trees none of which are very tall, nor do they have straight trunks from which long timbers for shipbuilding or house construction could be made. These particulars make a relevant reference to the history of Nantucket forests.

_bark_and_foliage.jpg.webp)

Oak building timber for houses and ships could not have been produced from island trees. Nantucket Island is a low altitude, sand dune environment with numerous ancient peat bogs and continual winds that are salt saturated. The highest points on Nantucket Island are Folger Hill at 109 feet above sea level, and Altar Rock at 108 feet. In the mid 20th century, only two small strips of good loam could be identified on the island, and both were shallow. Evidence indicates that the last tall forest trees on Nantucket died at least 2,000 years ago, portions of their trunks have been preserved in ancient peat bogs. These are remains of tree trunks whose maximum diameters were 12' and trunk height was only a few feet above ground, Trees of 20–25 feet tall are indicated, a height that can rarely be exceeded because of continual exposure to blowing, salt saturated wind. Tree trunk remains found in these ancient peat bogs belong to the only three species that can survive long exposure in such environments: cypress, red cedar and white cedar. These tree species require fresh water, they no longer grow on Nantucket and were never available nor appropriate for long building or ship timbers. Frequent exposure to high winds and blowing salt severely restricts the maximum possible height for both hardwood and coniferous tree species. A storm with salt saturated, winds of 60–80 mph will tear apart the top branches of a tree. Blowing salt also adheres to bark and leaves and relentlessly penetrates the wood to induce rot and tissue death. Trees in more protected sites are more than a few tall. Nonetheless, they are forced into a distorted growth pattern by the relentless, salt saturated wind. Maximum height is severely reduced, and their profile is very distinctive as seen in Theodore Robinson's painting done in 1882.

"On Nantucket, oak, pine and beech can attain heights of only a few feet, albeit with distorted trunks whose width would suggest a tall tree of the usual height. A typical black oak (Quercus velutina) so formed, might have a 20" trunk diameter but a morphology that is severely restricted by 'wind pruning' and thereby less than one foot tall with branches buried or growing along the ground; or alternatively, many feet wide at the base but less than two feet in height to the fork in the trunk where branches form. Cedar roots can spread and coalesce on the ground creating a large mass of wood that has almost no height and is not a tree trunk. Low hills on the north east sector of the island afforded protection from severe wind pruning in the past but severe Erosion since 1896 has greatly reduced the altitude of these hills. In some protected niches, oak and beech trees did grow to 20–25 feet tall and were often cut when about 50 years of age for fence posts and firewood. A period of intense cutting of the remaining oak and beech trees of this size and age has been identified in the late 19th century.[3]

A consistent exception to this dwarfing of tree species is the Japanese Black Pine. It has evolved in an environment nearly identical to that of Nantucket, and was introduced in the late 19th century . Pitch pine will also achieve some height in highly acidic soils but was likely nonexistent on Nantucket prior to 1847 when introduced to be used in windbreaks. "Small patches of dry upland soils within these forests contain some beautiful, old examples of American beech, black oak, white oak, and American holly, These tree species are now relatively rare on Nantucket." [4]

The photographs in this article portray a selection of swamps and bogs whose characteristics resemble those reconstructed for the ancient swamplands on Nantucket. They are a best effort at depicting what the ancient swamps, bogs and adjoining forest trees might have look liked on Nantucket more than 2,000 years ago.

Bog tree stump, Scotland

Bog tree stump, Scotland Acushnet Swamp, Massachusetts

Acushnet Swamp, Massachusetts Acushnet Cedar Swamp, Massachusetts

Acushnet Cedar Swamp, Massachusetts Hawley Bog, Massachusetts

Hawley Bog, Massachusetts Spruce Hole Bog, New Hampshire

Spruce Hole Bog, New Hampshire Heath Pond Bog, New Hampshire

Heath Pond Bog, New Hampshire

Wampanoag - canoes, long house, the forest

Indigenous peoples likely did not have access to New England until the Wisconsin Glaciation began to retreat ~16,000 BC. At its maximum advance, the great ice sheets had reached Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard islands. There is evidence that Paleo-Indians settled on Nantucket, those people who were present at the end of the last ice age throughout North America. Radiocarbon dating indicates a first appearance in New England, ~10,000 BC. Water was essential for fishing and longer distance trade. Early Woodland period cultures persisted until ~0 AD. On Nantucket, and indigenous tribes had access to forest trees tall enough to provide long tree trunks for canoes and the lodge until ~0 AD as indicated above.[5]

The Wampanoag predominated among the indigenous peoples of Nantucket upon European contact. They acquired this identity from John Smith in 1616. At this time. there were ~ 12,000 Wampanoag living in southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket and Elizabeth Island. Their language places them within the Algonquian family of Native Americans.[6]

Wampanoag resource procurement was based upon the seasonal cycles of plant and animal foods.[7]

There is little information available about Wampanoag maritime craft. Their boats were small and assuredly used frequently on coastal waters, rivers and streams when the Wampanoag were fishing and hunting. Canoes were also used for occasional trading trips to other islands and the mainland. The short trees of Nantucket could provide logs from which to make a small canoe. Birch was very rare, if present at all, and if birch bark canoes were on Nantucket, they were imported.

The largest building in Wampanoag village architecture was the long house that housed several families during winter in sheltered valleys. Long house construction did not require the large building timbers that were necessary to build English style houses and town buildings. As with all indigenous peoples who were both hunter/gatherers and agriculturalists, resources in all ecological niches that provided food were treated carefully with an understanding about conserving habitat and breeding populations for the long run. The very ancient Nantucket forests that had tall trees disappeared for reasons that had nothing to do with Wampanoag ancestor's utilization of the forest.

We can only conclude that architectural and ship building timber of large size was not available to the early European and American colonists of Nantucket island, nor to the first nation Wampanoag people who frequented offshore waters, rivers and streams to hunt and fish throughout the year.

See also

References

- ↑ Nantucket nearly treeless. - In "Natural Habitats of Nantucket", (Nantucket Conservation Foundation), 1999-2006. Retrieved on Oct.3, 2008.

- ↑ Nantucket's Forests 1 - The absence of rich soil. In "Was Nantucket Ever Forested?" Originally published in Historic Nantucket, Vol 14, no. 4 (April 1967), p. 15-22 (Nantucket Historical Association). Retrieved on Oct.3, 2008.

- ↑ Nantucket Forests 2 - How Old, How Tall? In "Was Nantucket Ever Forested?" published in Historic Nantucket, Vol 14, no. 4 (April 1967), p. 15-22 (Nantucket Historical Association). Retrieved on Oct.3, 2008.

- ↑ Nantucket Forests 3 - Two tall pine species post date Brant Point ship building.In "Was Nantucket Ever Forested?" Originally published in Historic Nantucket, Vol 14, no. 4 (April 1967), p. 15-22 (Nantucket Historical Association). Retrieved on Oct.3, 2008.

- ↑ Norfolk Indians, January 26, 2010, retrieved February 8, 2011 The last of the Pleistocene megafauna would rapidly leave New England as the coldest climates retreated north. Local peoples quickly developed multi-resource economies in which strategies were developed to exploit almost every plant and animal in the local environment that was edible. Dogs were domesticated. The Archaic period in the Americas followed PaleoIndian societies ~8,000 BC and persisted until ~1,000 BC. Rising sea levels separated Nantucket from Cape Cod ~5,000 BC, during the Middle Archaic Period.

- ↑ Wampanoag populations The former territory of the Wampanoag was central, eastern and southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Island; Connecticut, Rhode Island and the outer half of Long Island. Their population numbered about 12,000 before disease and war nearly exterminated the several Wampanoag tribes in the 17th century. At European contact there were about 4,000 Wampanoag on Martha's Vinyard and Nantucket. These island populations had been reduced to 700 by 1763 when a fever epidemic nearly wiped out everyone. The last Wampanoag on Nantucket died in 1855. Retrieved on Oct.3, 2008.

- ↑ Wampanoag resource utilization In winter on Nantucket, ice fishing could be productive and small game were hunted. In the spring, fishing commenced in earnest (cod, flounder, mackerel, lobster, molluscs), muskrat were hunted, fields planted (gourds, pumpkin, tobacco, squash, corn), and maple sap gathered. In the summer, berries, wild onions and shellfish were collected, fishing continued and crops were tended. As fall arrived, crops were harvested, chestnuts, acorns and chestnuts were collected. As winter approached, hunting continued (deer, rabbits, squirrel, raccoon, muskrat, otter, geese, turkey) Retrieved on Oct.3, 2008.

External links

- "Natural Habitats of Nantucket" Nantucket Conservation Foundation, 1999-2006.

- "Was Nantucket Ever Forested?" Originally published in Historic Nantucket, Vol 14, no. 4 (April 1967), p. 15-22 (Nantucket Historical Association).

- Wampanoag history First Nations Site Index and Search Tool, 1996.

- Wampanoag, culture and land use, Wampanoag history Indian Education Program, Anchorage School District, October 1993.

- Wampanoag Canoe Passage, Taunton River Organization, nd.

- The Chestnut Story - Pequot Built Solid Chestnut Canoes, by Bill Adamsen, February 10, 2009. The Pequot were an Algonquian people, and thus closely related to the Wampanoag of Nantucket.