| Kansallisarkisto (in Finnish) Riksarkivet (in Swedish) | |

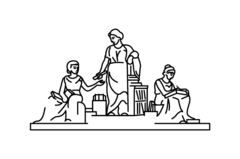

Insignia of the National Archives. | |

Main building of the Finnish National Archives on the Rauhankatu Street in Helsinki. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 25, 1816 |

| Headquarters | Rauhankatu 17, Helsinki 60°10′18″N 24°57′09″E / 60.17171°N 24.95240°E |

| Employees | 240 |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent department | Ministry of Education and Culture |

| Website | kansallisarkisto |

The National Archives of Finland (Finnish: Kansallisarkisto; Swedish: Riksarkivet) is a Finnish government agency under the Ministry of Education and Culture. It is responsible for archiving official documents of the Finnish state and municipalities. It consists of three locations in the capital Helsinki and seven former regional archives, which were incorporated into the National Archives in 2017 and have since been its branches.

The task of the National Archives is to ensure official documents forming a part of national heritage are preserved. It is the official Finnish authority in archiving, and promotes the preservation of documents located in private archives. In addition, the National Archives provides their stored documents for research use and participates in research and development activities.[1] The National Archives is also the authority in heraldry. It ratifies all heraldic emblems used by the government, municipalities and church, and flags used by yacht clubs and military units. Its library has special collections on archiving, heraldry and sigillography.

The archives was created in 1816 as part of the Senate of Finland.[2] The present main building in Helsinki was built in 1890.[3] The present Swedish name was adopted in 1939 and the present Finnish name in 1994. It was in 1939 it also became a central government agency of its own.

Organization

The National Archives is led by the Director General, who has the title of National Archivist. It has some 240 employees, and its functions are divided into four sectors: Collections Management, Information Services, Research Development, and Operations Control.[4]

Collections Management

Collections Management acquires and receives documents and ensures their preservation and availability for use. Any tasks related to the lifespan of archived documents are its responsibility.[5]

Information Services

Information Services is responsible for making the archived documents available to citizens. It controls the reading rooms, online services, research and reproduction services and archive pedagogic functions.[5]

Research Development

Research Development promotes cooperation with research communities and controls research and development projects.[5]

Operations Control

Operations Control is responsible for planning and tracking and offers support to the other sectors.[5]

Locations

The National Archives has a presence in nine cities and municipalities: Helsinki, Hämeenlinna, Inari, Joensuu, Jyväskylä, Mikkeli, Oulu, Turku and Vaasa. The total combined amount of archived material is about 210 shelf kilometres.

Main Branch

The main location is on Rauhankatu Street in Helsinki. It stores official archives of the central government and private archives of people who have influenced Finnish society. The oldest document is from 1316 and the most recent ones from the 21st century. Customer service in Helsinki is centered at Rauhankatu.

Hallituskatu

The Hallituskatu location in Helsinki stores the archives of all ministries except the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Defence and the Prime Minister's Office. In addition, archives of committees, boards and task forces active in or after 1998 are stored there. Hallituskatu also has a reading room.[6]

Siltavuori

The Siltavuori, Helsinki location houses less frequently used documents of the central government. It is the centre for digitization of the archives' material. The conservation and research for the technical preservation of documents is led from Siltavuori. The location has no customer service. The main building of the Sintavorri branch was originally as a granary of the Russian armed forces in 1885. From the beginning of independence until 1945, the building was a depot of the Finnish Defense Forces. In 1945, the building was given to the military archives. It was later assigned to the national archives in the late 1990s.[7]

Hämeenlinna

The Hämeenlinna branch houses archives of local government offices and the church, private archives, some municipal archives and document reproductions stored on microfilm. The oldest documents are from the 17th century.[8]

Joensuu

The Joensuu branch receives documents from government offices in Northern Karelia and Northern Savonia. It also stores church archives, documents from societies, companies and private individuals and a large microfilm collection.[9]

Jyväskylä

The Jyväskylä branch stores documents from government officials, churches and individuals in the area. The oldest document is a letter written in Latin from 1535. As Jyväskylä is a city known for studies, the Jyväskylä branch also houses archives of schools and academies, including the microfilm collection of the Faculty of History of the University of Jyväskylä.[10]

Mikkeli

The Mikkeli branch has documents from the regions of Southern Savonia, Southern Karelia and Kymenlaakso. It also stores documents and maps from officials and churches of the parts of Karjala ceded to the Soviet Union after the Winter War, which were originally stored at the Vyborg Regional Archives. The oldest document in Mikkeli dates back to 1455.[11]

Oulu

The Oulu branch stores archives from local and regional governments. In addition, documents from about 2,500 societies, companies and private individuals form a notable part of the material stored in Oulu. The Oulu branch also houses the archives of Santa Claus, which has letters sent to Santa Claus from all over the world.[12]

Turku

The Turku branch houses archives of government offices in Southwest Finland and Satakunta as well as documents from congregations, societies, associations, companies and individuals. The oldest document stored there is a border inspection document from 1510, written on parchment.[13]

Vaasa

The Vaasa branch has archives from local officials of the Ostrobothnia region. The oldest document is a bill of sale from 1407.[14]

In addition to the seven branches (former regional archives), the National Archives also includes the Sami Archives in Inari, founded in 2012.[15] It stores documents from Sami officials and archives of individuals, families, societies and companies that are considered relevant to Sami research. It also has a recording archive for audiovisual material.[16]

Military Archives

The military archives were integrated in to the National Archives of Finland in 2008. The contain records on the Finnish Defense Forces dating from independence to the present, as well as private organizations and persons who had links with the defense administration.[7]

Directors

From 1880 onwards, the directors of the National Archives held the title of State Archivist. This was changed to Director General in 1992, although the title of State Archivist continues to be given to the current Director General.[17] Between 1949 and 1992, State Archivists were also given the title of Professor.[18]

The following is a list of State Archivists (1880–1992) and Directors General (1992–present) of the National Archives.[17]

- K. A. Bomansson (1880–1883)

- Reinhold Hausen (1883–1916)

- Leo Harmaja (1917)

- J. W. Ruuth (1917–1926)

- Kaarlo Blomstedt (1926–1949)

- Yrjö Nurmio (1949–1967)

- Martti Kerkkonen (1967–1970)

- Tuomo Polvinen (1970–1974)

- Toivo J. Paloposki (1974–1987)

- Veikko Litzen (1987–1996)

- Kari Tarkiainen (1996–2003)

- Jussi Nuorteva (2003–2022)

- Päivi Happonen (2022– )

Material

Documents

The oldest document in the National Archives is a letter of protection from Birger, King of Sweden to the women of Karelia, which is dated 1 October 1316.[19] From the middle ages, the archives has 66 original documents and 223 reproductions. The oldest continuous series of documents is the collection of the so-called vogt's accounts (Finnish: voudintilit), account books of local governments, the oldest of which are from the 1530s.[20]

A majority of the materials in the collections of the National Archives were written in Swedish, the second official language, as Finland remained under Swedish rule from the 13th into the 19th century.[7]

Although the majority of material in the archives comes from government officials,[20] it also has documents from private archives of political and social activists. For example, all the archives of the Presidents of Finland are in the National Archives.[21] The only exceptions are Martti Ahtisaari[7] and Urho Kekkonen, who founded his own archive in 1970.[22]

Maps

Most of the maps stored in the National Archives are a part of larger collections produced by government officials. The oldest collections are from the 17th century. The National Archives also has single maps and map collections from the archives of farms, map collectors and other individuals.[23] The largest single map collection is the renewal archive of the National Land Survey of Finland, which has 726,000 maps (including urbarium maps) and other related documents dated between the 17th and the 20th centuries.[24]

Access

In principle, all material stored in the National Archives is public and available to everyone for free. However, the usage of some material is restricted due to legislation, agreements made with donors, or the condition of the documents.[25]

The National Archives has several online services and databases for clients. Arkistojen Portti contains information about different types of documents and how to access them.[26] Astia is used to search and view all the material, including digital material, and to order documents to be studied in the reading rooms. It is also used for ordering documents to be delivered to different branches of the archives, requesting access to restricted documents, and ordering reproductions.[27]

Despite ongoing digital preservation and accessibility efforts, very little of the collections has been digitized. If you are hoping to access specific records in the National Archives of Finland, it may be necessary to contact them or visit their locations in-person.[7]

Genealogy

The National Archives of Finland has many resources for genealogical research for those interested in Finnish ancestry. Many records are available online through the 'Astia' web service. Their website is available in English, however the digitized documents have not been translated.[28][29]

Much of the genealogical records available at the National Archives of Finland consist of parish records from the Lutheran church. The Church Law of 1686 required Lutheran priests to keep parish records containing information on events such as births, marriages, and deaths. These records were used as official census lists for 300 years. As such, these records are notable for the length of time that they span and their accuracy.[30]

Preservation

The goal of records management is that all records older than 40 years old are catalogued and in order when transferred to the archives for permanent storage. Storage rooms for paper documents are kept at a temperature of 18 degrees Celsius and a relative humidity of 50%.[7]

Technical Unit

The technical unit is responsible for digitizing and microfilming. They concentrate on frequently requested items and those which are in poor condition. Digitized materials are then made available online.[7]

Conservation

Documents and other materials are repaired using methods that are reversible without damaging the document.[7]

Library

The library of the National Archives specialises on archiving, document diplomacy, heraldry and sigillography. Its collections include reference and source books, official publications, literature on the history of Finland and the surrounding areas, justice, management and social science as well as personal and family histories. The library serves primarily research based on archives and documents, customers wanting to retrieve information and on-duty staff. The library is responsible for all literature and other material necessary for customer service and activities at the archives. In its field of expertise, the library of the National Archives is the only library that is a part of Finnish national library network.[31]

The library's collection comprises about 334,000 volumes from Finland and abroad and around 200 magazines in various languages.[32] In addition to literature on archiving, history and source books, the library has a large collection of books on heraldry and sigillography, and it also has a historically significant amount of literature printed prior to 1850. The collection is mainly expanded with books on archiving, document management, archive usage and heraldry. Whenever possible, key pieces of literature about basic research of the history of Finland are also acquired. Donations received by the library mainly cover the topics of genealogy and local history.[31]

Books in the open collection are freely available for use in the reading rooms. Publications in the closed collection must be ordered for use. Home loans are not allowed.[31] However, it is possible to order material to be delivered to other branches of the National Archives,[32] and it is also possible to acquire reproductions. All material in the open collection and all serial publications have been imported into Erkki, a database for Finnish special libraries maintained by the National Library of Finland. The importing of stored books into the database is also underway.[31]

Art and Architecture

The National Archives of Finland's main building was designed by Gustaf Nyström and completed in 1890 in the Neo-Renaissance style.[33] The main building of the National archives was the first building designed specifically for archival purposes in the Nordic countries and the entire Russian Empire.[7] The building has since been expanded.

The neoclassical sculpture above the roof of the entrance to the main building of the National Archives of Finland was designed by sculptor Carl Eneas Sjöstrand. The sculpture depicts three female figures. The center figure is a personification of Finland and she hands a role of parchment to the muse of history to her right. The figure on the viewer's right, the muse of source criticism, reads a large book. This trio of classical figures is also the seal and emblem of the national archives. The Latin inscription under the figures reads “ARCHIVVM FINLANDIAE PVBLICVM,” which translates to “the Public Archives of Finland.”[7]

Events

100th Independence Day Celebration

On December 6, 2017, Finland celebrated its 100th anniversary as in independent nation. Events were held across Finland where volunteers and participants would stand in a moment of silence by the graves of soldiers who died fighting for independence. Volunteers were matched to graves of soldiers who were of the same age, highlighting that most war victims were young.

In preparation for the event, some volunteers and participants were invited to the National Archives of Finland to study records of soldiers buried at the cemetery by the Church of St. Lawrence, Vantaa, or Vantaan Pyhän Laurin kirkko in Finnish. The records studied were primarily those of military service.[34]

References

- ↑ "Laki Kansallisarkistosta". Finlex.fi (in Finnish). Ministry of Justice. 16 December 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Nuorteva, Jussi; Happonen, Päivi (2016). Suomen arkistolaitos 200 vuotta – Arkivverket i Finland 200 år [200 Years of Finnish Archive Services] (in Finnish and Swedish). Helsinki: Edita Publishing. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-951-37-7003-7.

- ↑ Nuorteva, Jussi; Happonen, Päivi (2016). Suomen arkistolaitos 200 vuotta – Arkivverket i Finland 200 år [200 Years of Finnish Archive Services] (in Finnish and Swedish). Helsinki: Edita Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-951-37-7003-7.

- ↑ "Task and organization". National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Arkistolaitos uudisti organisaationsa" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Kansallisarkiston aineistot Hallituskadulla". Arkistojen Portti (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 “National Archives of Finland: Introduction,” Kansallisarkisto, February 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Aineistot Hämeenlinnassa" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Aineistot Joensuussa" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Aineistot Jyväskylässä" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Aineistot Mikkelissä" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Aineistot Oulussa" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Aineistot Turussa" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Aineistot Vaasassa" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Suoninen, Inger-Elle (30 June 2015). "Filosofian tohtori Inker-Anni Linkola ylitarkastajaksi Saamelaisarkistoon" (in Finnish). Yleisradio. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Saamelaisarkiston aineistot" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- 1 2 Nuorteva, Jussi; Happonen, Päivi (2016). Suomen arkistolaitos 200 vuotta – Arkivverket i Finland 200 år [200 Years of Finnish Archive Services] (in Finnish and Swedish). Helsinki: Edita Publishing. p. 474. ISBN 978-951-37-7003-7.

- ↑ Nuorteva, Jussi; Happonen, Päivi (2016). Suomen arkistolaitos 200 vuotta – Arkivverket i Finland 200 år [200 Years of Finnish Archive Services] (in Finnish and Swedish). Helsinki: Edita Publishing. pp. 214, 229, 246, 282, 302. ISBN 978-951-37-7003-7.

- ↑ Nuorteva, Jussi; Happonen, Päivi (2016). Suomen arkistolaitos 200 vuotta – Arkivverket i Finland 200 år [200 Years of Finnish Archive Services] (in Finnish and Swedish). Helsinki: Edita Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-951-37-7003-7.

- 1 2 "Kansallisarkiston aineistot" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ Forssell, Christina; Nuorteva, Jussi (2007). "Kansallisarkisto". In Itkonen, Satu; Kaitavuori, Kaija (eds.). Kansalliset kulttuurilaitokset (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. pp. 33–36.

- ↑ "UKK-arkiston historia" (in Finnish). Urho Kekkosen arkisto. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ "Kartat". Arkistojen Portti (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ "Maanmittaushallituksen uudistusarkisto". Arkistojen Portti (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ "Näin käytät aineistojamme" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ "Verkkopalvelut ja tietokannat" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ "Astia – Access service of the National Archives". Astia (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ↑ “Genealogical research,” National Archives of Finland, http://www.arkisto.fi/en/access/roots-in-finland-genealogical-research-at-the-national-archives.

- ↑ “Astia” web service, National Archives of Finland, https://astia.narc.fi/uusiastia/

- ↑ “Roots in Finland – but how can I find them?” Kansallisarkisto, July 4, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Kansallisarkiston kirjasto" (PDF) (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Kirjastomme palvelee" (in Finnish). National Archives of Finland. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ “National Archives of Finland,” https://www.myhelsinki.fi/en/see-and-do/sights/national-archives-of-finland

- ↑ “When Finland's 100th Independence Day Started at the Archives”, National Archives of Finland, Oct 23, 2018, video.