| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Myanmar |

|---|

|

| People |

The national symbols of Myanmar (also known as Burma) are icons, symbols and other cultural expressions which are seen as representative of the Burmese people. These have been accumulated over centuries and are mainly from the Bamar majority, while other ethnic groups also maintain their own symbols.

No official codification or de jure recognition exists, but most of these symbols are seen as de facto representative of the Burmese people. The use of much of these symbols were cultivated during the Konbaung dynasty which ruled the country from 1761 to 1885.

Flora

The Burmese ascribe a flower to each of the twelve months of the traditional Burmese calendar.[1] However, two flowers are seen as national symbols.

|

The padauk (Burmese: ပိတောက်) is referred to as the national flower of Myanmar and is associated with the Thingyan period (Burmese New Year, usually mid-April). Unfortunately, it is often mistaken with the Cassia fistula (Ngu-wah), which is the national flower of Thailand.[2] |

_pl._7938_(1904).jpg.webp) |

The Bulbophyllum auricomum or thazin orchid (Burmese: သဇင်) is another national flower.[2] According to a Burmese poem, during the Konbaung era, the king had the right to claim the first flowering bud of thazin within the realm and any transgression was punishable by death. |

_flower_in_Hyderabad%252C_AP_W_IMG_6604.jpg.webp) |

The ingyin (အင်ကြင်း) is the third national flower of Myanmar.[2] |

Fauna

|

The green peafowl, called the 'daung' (Burmese: ဒေါင်း) or u-doung (ဥဒေါင်း) in Burmese, is one of the national animals of Myanmar. In Burmeses traditions, peafowl is regarded as a symbol of the descendence of the sun.[3]

The dancing peacock, ka-daung (Burmese: ကဒေါင်း) was used as the symbol of the Burmese monarch. During the period of Konbaung Dynasty, the dancing peacock on a red sun is charged on the State seal and the national flag. It was also stamped on the highest denominator coins minted by the Konbaung dynasty. Because of this association with the Konbaung monarchy, the anti-colonial nationalist movements widely used it. It also appeared on national flags of British Burma and also the State flag of the State of Burma. Upon independence, it was again featured on Burmese banknotes from 1948 til 1966. An alternative pose, to denote struggle, is the fighting peacock, khut-daung (Burmese: ခွပ်ဒေါင်း), the style originally created as the symbol of the students movement in 1920s. The party flag of National League for Democracy also features it. |

.svg.png.webp) |

The stylized leograph of Burmese lion (Burmese: ခြင်္သေ့), found mainly in front of pagodas and temples. The main throne of the later Konbaung dynasty was the Golden Lion Throne (Burmese: သီဟာသနပလ္လင်). In 1947, the Constituent Assembly of the Union of Burma put 3 lions in the State Seal giving the reason that lion is the symbol of bravery, diligence, defeating the enemies and purity according to ancient believes, so the citizens should emulate those characteristics; and the lions surrounding the map in the State seal means the State being secured.[4]: 10 The lion from the top was replaced with a star in 1974, but the latter two are still present in the State seal.

After 1988, lion began to appear on almost all denominations of Burmese banknotes and coins (1999). |

|

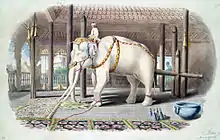

The white elephant (Burmese: ဆင်ဖြူတော်) is another symbol of state associated with the days of the monarchy. Like in neighbouring Thailand, the white elephant is revered as a blessing towards the entire country. The importance of the white elephant to Burmese and Theravada culture can be traced to the role which white elephants play in Buddhist cosmology and the Jatakas. Hsinbyushin, the name of a Konbaung King means 'Lord of the White Elephant'. |

Food

A popular saying states "A thee hma, thayet; a thar hma, wet; a ywet hma, lahpet" (အသီးမှာသရက်၊ အသားမှာဝက်၊ အရွက်မှာလက်ဖက်), translated as "of all the fruits, the mango's the best; of all the meats, the pork's the best; and of all the leaves, lahpet's (tea) the best".

|

Mohinga is the de facto national dish of Myanmar.[5] It is a rice noodle dish served with thick fish broth and is generally eaten for breakfast. The main ingredients of the broth are catfish, chickpea flour, lemongrass, banana stem, garlic, onion, ginger and ngapi. |

.JPG.webp) |

Laphet thoke is another symbolic dish of Myanmar, albeit a snack. It consists of pickled tea leaves soaked in oil eaten with an assortment of fritters including roasted groundnuts, deep fried garlic, sun dried prawns, toasted sesame and deep fried crispy beans. Laphet is served in a traditional 'oat' - a lacquer container with individual compartments for each ingredients. Lahpet was an ancient symbolic peace offering between warring kingdoms in the history of Myanmar, and is exchanged and consumed after settling a dispute. |

Sport

|

Chinlone is the national sport of Myanmar.[6] A non-competitive sport, the game focuses on players attempting to exhibit moves designed to prevent the ball from touching the ground, without using their hands. Mandalay is a major centre for playing and learning chinlone. |

Musical instruments

|

The saung or Burmese harp, is the national musical instrument of Myanmar.[7] Although not used much in modern music, it is seen as the epitome of Burmese culture. It is the only surviving harp in Asia.[8] |

|

The hne is a Burmese oboe and also another national instrument. |

See also

References

- ↑ Flowers of Myanmar

- 1 2 3 "NLD criticise government's choices for national symbols". Democratic Voice of Burma. DVB Multimedia Group. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ မြန်မာဖတ်စာ ပဉ္စမတန်း (Grade-6) [Myanmar Textbook for Fifth Standard (Grade-6)] (in Burmese). Ministry of Education, Government of the Union of Myanmar. 1999. p. 3.

- ↑ "ပြည်ထောင်စု သမတမြန်မာငံနိုင် အလံတော်" [Flag of Union of Republic of Burma]. ဖဆပလ သတင်းစဉ် [AFPFL News]. 9 August 1947.

- ↑ Withaya Huanok (November 2009). "Mohinga Memories". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Aung-Thwin, Maitrii (2012). "Towards a national culture: chinlone and the construction of sport in post-colonial Myanmar". Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics. 15 (10): 1341–1352. doi:10.1080/17430437.2012.744206.

- ↑ "Saùng-gauk (Arched Harp), Burma (Myanmar), ca. 1960". National Music Museum. The University of South Dakota. 21 September 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Miller, Terry E. and Sean Williams. The Garland handbook of Southeast Asian music. Routledge, 2008. ISBN 0-415-96075-4