Jolof Empire امبراطورية جولوف | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1200–1549 | |||||||||||||||||||||

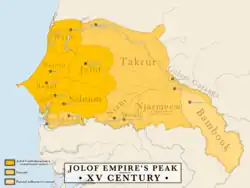

Map of the Jolof Empire's borders, including tributary states and territories of influence. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Warxox | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Wolof, Serer | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Traditional African religion, Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor (Buur-ba Jolof) | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1350 - 1370 | Ndiadiane Ndiaye | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1543–1549 | Leele Fuli Fak | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 1200 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Battle of Danki: empire reduced to a rump kingdom | 1549 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Senegal | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Senegal |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The Jolof Empire (Arabic: امبراطورية جولوف), also known as Great Jolof,[1] or the Wolof Empire, was a Wolof and Sereer confederacy state that ruled parts of West Africa, most precisely modern-day Senegal, Mali, Gambia and Mauritania from around the 12th century[2][3][4][5] [6][7]to 1549. Following the 1549 battle of Danki, its vassal states were fully or de facto independent; in this period it is known as the Jolof Kingdom.

Origins

Date of founding

Although it is seldom claimed that Ndiadiane Ndiaye's foundation of the Jolof Empire dates to the 14th century, after it supposedly gained independence from the Mali Empire, it's real advent may have taken place in the 13th, or even 12th century.

John Donnelly Fage suggests, however, dates in the early 13th century are usually ascribed to this king and the founding of the empire, a more likely scenario is "that the rise of the empire was associated with the growth of Wolof power at the expense of the ancient Sudanese state of Takrur, and that this was essentially a fourteenth-century development."[8]: 484

A number of scholars even date the founding of Jolof in the 12th century, as cited by David P. Gamble, Linda K. Salmon and Alhaji Hassan Njie, in the Wolof chapter of The Peoples of the Gambia. Its founding is associated with the upheavals and migrations which followed the decline of Wagadou at the end of the 11th century.

Epic Of Ndiadiane Ndiaye

Traditional accounts among the Wolof agree that the founder of the state and later empire was the possibly mythical Ndiadiane Ndiaye (also spelled Njaajaan Njaay or Njai).[8]: 484 , a Waalo-Waalo[9] prince of Fulani or Toucouleur origins;[10] Despite he is believed to have been of Almoravid arabo-berber origin, the claim of Ndiadiane Ndiaye being so is rather a a-historical fabrication with the purpose of claiming an ethnic background believed to be "closer to Islam". As a matter of fact, the less islamic influenced sereer tradition maintain that Ndiadiane Ndiaye was of Fulani origin and had absolutely no trace of arabo-berber affiliations whatsoever.[11]

Overall Ndiadiane Ndiaye's origins vary; The most common version claiming arabic descent, as reported by James Searing, writes that he was "the first and only son of a noble and saintly 'Arab' father Abdu Darday and a 'Tukuler' woman, Fatoumatu Sall".[12][6] Sallah writes: "Some say that Njajan was the son of Abu Darday, an Almoravid conqueror who came from Mecca to preach Islam in Senegal ... Some say that Ndiadiane Ndiaye was a mysterious person of Fulani origin. Others say he was a Serer prince."[5] Brooks reports that some oral histories hold that Ndiaye was the son of Abu Bakr ibn Umar, although this ancestry is unlikely considering Abu Bakr's death in 1087.[13][14]

All of the origins cited above give Ndiaye an Almoravid Islamic lineage and a link on his mother's side to the state of Takrur. James Searing adds that "In all versions of the myth, Njaajaan Njaay speaks his first words in Pulaar rather than Wolof, emphasizing once again his character as a stranger of noble origins."[12] The legend of Ndiadiane Ndiaye begins when his father dies and his mother remarries with a Mandinka slave. This match so enfuriated Ndiaye that he jumped into the Senegal River near Bakel and began an aquatic life. He made his way downstream to the Kingdom of Waalo, where he was born.[14]: 113

At this time, Waalo was divided into villages ruled by separate kings using the Serer title Lamane,[3] some of whom were engaged in a dispute over a wood near a prominent lake. This almost led to bloodshed among the rulers but was stopped by the mysterious appearance of a stranger from the lake. The stranger divided the wood fairly and disappeared, leaving the people in awe. The people then feigned a second dispute and kidnapped the stranger when he returned. They offered him the kingship of their land and convinced him to do so and become mortal by offering him a beautiful woman to marry. When these events were reported to the ruler of the Sine, also a great magician, he is reported to have exclaimed "Ndiadiane Ndiaye" in his native Serer language in amazement.[15]: 21 The ruler of the Kingdom of Sine (Maad a Sinig Maysa Wali) then suggested all rulers between the Senegal River and the Gambia River voluntarily submit to this man, which they did.[15]: 22

Fearing writes that "Most versions of the myth explain how the new dynasty superimposed itself upon a preexisting social structure dominated by the Laman, Wolof elders who claimed 'ownership' of the land as the descendants of the founders of village communities. The laman retained many of their functions under the new monarchical order, becoming a kind of lesser nobility within the new state, and serving as electors when the time came to choose a new king from the Njaay dynasty."[12]

History

Early history

The new state of Djolof, named for the central province where the king resided, was a vassal of the Mali Empire for much of its early history.[8]: 381 Djolof remained within that empire's sphere of influence until the latter half of the 14th century.[8]: 456 During a succession dispute in 1360 between two rival lineages within the Mali Empire's royal bloodline, the Jolof became permanently independent.[7] A close examination of Jolof's societal and political structure reveals that at least some of its institutions may have been borrowed directly or developed alongside those of its larger predecessor.

Apogee and European trade

During the relatively dry period (c. 1100–1500) the Jolof empire expanded soutwards and westwards, progressively 'Wolofizing' the ruling classes of the smaller states thus incorporated into the empire. Beginning the 1440s, Portuguese ships began to visit the coast, initially looking to capture slaves but soon shifting to trade. The Jolof expansion may have been assisted by the purchase of horses from these traders.[14]: 114 At this time, Jolof was at the height of its power, and the Bur had extended his authority over Takrur,[18][19] Namandirou[20] (called Njarmeew[21][22] at the time), the Mandinka states on the northern bank of the Gambia, including Niumi, Badibu, Nyani, and Wuli.[23][24] This was in addition to the longtime vassal states of Cayor, Baol and Waalo, and the Serer states of Sine and Saloum,[25][26] which were the constituent states of the Jolof confederacy.

Furthermore, Jolof would also expand it's control over the gold trade, conquering Galam (or Gajaaga)[27] and subsequently Bambuk,[28] although Jean Boulègne argues of such conquest being very unlikely.[29] Either way, portuguese sources still marked bambuk as one of the provinces gained after the Jolof expansion.

In the 1480s, Jelen, the bumi or prince, was ruling the empire in the name of his brother Bur Birao. Tempted by the Portuguese trade, he moved the seat of government to the coast to take advantage of the new economic opportunities. Other princes, opposed to this policy, deposed and murdered the bur in 1489. Jelen escaped and sought refuge with the Portuguese, who took him to Lisbon. There he exchanged gifts with King John II and was baptized. Faced with the opportunity to put a Christian ally on the throne, John II sent an expeditionary force under a Portuguese commander to put the prince back on the throne of Jolof. The objective was to put him on the throne and a fort at the mouth of the Senegal River. Neither goal was achieved. A dispute between the commander and the prince resulted in the former accusing the bumi of treachery and killing him.[8]: 457

Late period

Despite internal feuds, the Jolof Empire remained a force to be reckoned with within the region. In the early 16th century, it was capable of fielding 100,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry.[15]: 23 But the seeds of the empire's destruction had already been sown by the Atlantic Trade.

Virtually everything that had given rise to the great Jolof Empire was now tearing it apart. Coastal trade, for instance, had brought extra wealth to the empire. But the rulers of the vassal states on the coast got the lion's share of the benefits, which eventually allowed them to eclipse and undermine the emperor.[8]: 457 Jolof was located far from the coast, and had to direct access to maritime trade.

There was also the matter of external forces, such as the breakup of the Mali Empire. Mali's slipping grip on its far-flung empire, thanks to the growth of the Songhai Empire, had allowed Jolof to become an empire itself. But now conflicts in the north were spreading to Jolof's northern territories. In 1513, Koli Tenguella led a strong force of Fulani and Mandinka into Futa Toro, seizing it from the Jolof and setting up his dynasty. Koli, whose father was killed fighting against the Songhai Empire, may have decided to act against the Jolof as an alternative to fighting the Songhai or Mandinka.[15]: 23 In 1520 the Serer kingdoms of Sine and Saloum in the south broke away.[30]

Battle of Danki and disintegration

In 1549, Kayor successfully broke from the Jolof Empire under the leadership of the crown prince Amari Ngoone Sobel Fall by defeating Jolof at the Battle of Danki. The battle caused a ripple effect resulting in Waalo and Baol also leaving the empire.[30] By 1600, the Jolof Empire was effectively over. Kayor invaded its southern neighbor, Bawol, and began forming a personal union of its own. Jolof was reduced to a kingdom; nevertheless, the title of Burba remained associated with imperial prestige and commanded nominal respect from its ancient vassals.[8]: 457

Society

The Portuguese arrived in the Jolof Empire between 1444 and 1510, leaving detailed accounts of a very advanced political system.[8]: 456 There was a developed hierarchical system involving different classes of royal and non-royal nobles, free men, occupational castes, and slaves. Occupational castes included blacksmiths, jewelers, tanners, tailors, musicians, and griots.[8]: 484 Smiths were important to the society for their ability to make weapons of war as well as their trusted status for mediating disputes fairly. Griots were employed by every important family as chroniclers and advisors, without whom much of early Jolof history would be unknown.[15]: 26 Jolof's nobility were nominally animists, but some combined this with Islam.[8]: 486 However, Islam had not dominated Wolof society until about the 19th century,[15]: 26 when the empire had long been reduced to a rump state in the form of the Kingdom of Jolof.

Women

Throughout the different classes, intermarriage was rarely allowed. Women could not marry upwards, and their children did not inherit the father's superior status.[15]: 26 However, women had some influence and role in government. The Linger or Queen Mother was head of all women and very influential in state politics. She owned several villages that cultivated farms and paid tribute directly to her. There were also other female chiefs whose main task was judging cases involving women. In the empire's most northern state of Walo, women could aspire to the office of Bur and rule the state.[15]: 26

Political organization

The Jolof Empire was organized as five coastal kingdoms from north to south, which included Waalo, Kayor, Baol, Sine and Kingdom of Saloum. All of these states were tributary to the land-locked state of Jolof. The ruler of Jolof was known as the Bour ba, and ruled from the capital of Linguère.[8]: 484 Each Wolof state was governed by its ruler appointed from the descendants of the founder of the state.[15]: 25 State rulers were chosen by their respective nobles, while the Bour was selected by a college of electors which also included the rulers of the five kingdoms.[8]: 457 There was the Brak of Waalo,[15]: 26 the Damel of Kayor,[8]: 457 the Teny (or Teigne) of Baol,[15]: 24 as well as the two Lamanes of the Serer states of Sine and Saloum.[15]: 21 Each ruler had practical autonomy but was expected to cooperate with the Bour on matters of defense, trade, and provision of imperial revenue. Once appointed, officeholders went through elaborate rituals to both familiarize themselves with their new duties and elevate them to a divine status. From then on, they were expected to lead their states to greatness or risk being declared unfavored by the gods and being deposed. The stresses of this political structure resulted in a very autocratic government where personal armies and wealth often superseded constitutional values.[15]: 25

Serer tradition says that the Kingdom of Sine never paid tribute to Ndiadiane Ndiaye nor any his descendants at Jolof. It further states that the Sine was never subjugated by Jolof and that the probably mythical Ndiadiane himself received his name from the mouth of Maysa Wali (king of Sine).[2]

Sylviane Diouf states that "Each vassal kingdom—Walo, Takrur, Kayor, Baol, Sine, Salum, Wuli, and Niani—recognized the hegemony of Jolof and paid tribute."[31]

See also

- Constituent parts of the Jolof Empire, roughly going north to south:

- Ethnic groups of the Jolof Empire:

- History of the Gambia

- History of Senegal

- The Kingdom of Jolof, which succeeded the Jolof Empire

- List of rulers of Jolof

- Mali Empire

References

- ↑ Tymowski, Michał (2020-09-07). Europeans and Africans: Mutual Discoveries and First Encounters. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-42850-8.

- 1 2 Diouf, Niokhobaye; Becker, Charles; Martin, Victor (1972). "Chronique du Royaume du Sine par suivie de Notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le Royaume du Sine". Bulletin de l'Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire, Série B (in French). 34 (4): 706.

- 1 2 Boulègue, Jean (1987). Le Grand Jolof, XIIIe-XVIe siècle (in French). Blois: Façades. p. 30. ISBN 9782907233002.

- ↑ Gamble, David P.; Salmon, Linda K.; Njie, Alhaji Hassan (1985). Peoples of the Gambia: The Wolof. I. San Francisco State University, Department of Anthropology. p. 3.

- 1 2 Sallah, Tijan M., Wolof: (Senegal), Rosen (1995), p. 21 ISBN 9780823919871

- 1 2 Fiona Mc Laughlin; Salikoko S. Mufwene (2008). "The Ascent of Wolof as an Urban Vernacular and National Lingua Franca in Senegal". In Vigouroux, Cécile B.; Mufwene, Salikoko S. (eds.). Globalization and Language Vitality: Perspectives from Africa. Continuum. p. 148. ISBN 978-0826495150. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011.

- 1 2 Ogot, Bethwell A. (1999). General History of Africa V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-520-06700-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland, eds. (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521209816.

- ↑ Reutner, Ursula (2023-12-18). Manual of Romance Languages in Africa. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-062617-9.

- ↑ Research in African Literatures. African and Afro-American Studies and Research Center, University of Texas [at Austin]. 2006.

- ↑ Gamble, David P.; Salmon, Linda K.; Njie, Alhaji Hassan (1985). Peoples of the Gambia: The Wolof. I. San Francisco State University, Department of Anthropology.

- 1 2 3 Searing, James (2003). West African Slavery and Atlantic Commerce: The Senegal River Valley, 1700–1860. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0521534529.

- ↑ Host Bibliographic Record for Boundwith Item Barcode 30112044298542 and Others (in French). 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Western Africa to c1860 A.D. A provisional historical schema based on climate periods" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Stride, G. T.; Ifeka, Caroline (1971). Peoples and Empires of West Africa: West Africa in History 1000–1800. Walton-on-Thames: Nelson. pp. 21–26. ISBN 9780175114481.

- ↑ Sallah, Tijan M. (1995-12-15). Wolof: (Senegal). The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8239-1987-1.

- ↑ Diop, Papa Samba (1993). The Oral History and Literature of the Wolof People of Waalo, Northern Senegal: The Master of the Word (Griot) in the Wolof Tradition : Performance of the Epic Tale of the Waalo Kingdom and the Transmission of Knowledge. University of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ DeCorse, Christopher (2016-10-06). West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade: Archaeological Perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-9105-7.

- ↑ Diouf, Sylviane A. (November 1998). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1905-3.

- ↑ Bertrand, FAUVELLE-AYMAR François-Xavier, HIRSCH (2013-07-02). Les ruses de l'historien. Essais d'Afrique et d'ailleurs en hommage à Jean Boulègue (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0940-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ T, Gayibor Nicoué; Moustapha, Gomgnimbou; Dominique, Juhé-Beaulaton (2013-06-20). L'écriture de l'histoire en Afrique (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-2289-8.

- ↑ Bertrand, FAUVELLE-AYMAR François-Xavier, HIRSCH (2013-07-02). Les ruses de l'historien. Essais d'Afrique et d'ailleurs en hommage à Jean Boulègue (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0940-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bertrand, FAUVELLE-AYMAR François-Xavier, HIRSCH (2013-07-02). Les ruses de l'historien. Essais d'Afrique et d'ailleurs en hommage à Jean Boulègue (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0940-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Diouf, Sylviane A. (November 1998). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1905-3.

- ↑ Charles 1977, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Diouf, Sylviane A. (November 1998). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1905-3.

- ↑ Bathily, Abdoulaye (1989). Les portes de l'or: le royaume de Galam, Sénégal, de l'ère musulmane au temps des négriers, VIIIe-XVIIIe siècle (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7384-0276-9.

- ↑ Saglio, Christian (1983). Guide de Dakar et du Sénégal (in French). Société africaine d'édition.

- ↑ Jean, BOULEGUE (2013-03-18). Les royaumes wolof dans l'espace sénégambien (XIIIe-XVIIIe siècle) (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0881-6.

- 1 2 Charles 1977, pp. 3.

- ↑ Diouf, Sylviane (1998). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. New York University Press. p. 19. ISBN 081472082X.

Sources

- Charles, Eunice A. (1977). Precolonial Senegal : the Jolof Kingdom, 1800-1890. Brookline, MA: African Studies Center, Boston University. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1999). General History of Africa V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 512 Pages. ISBN 0-520-06700-2.