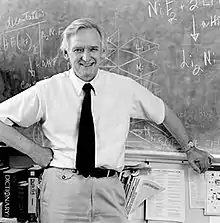

Neil Bartlett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 September 1932 Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England |

| Died | 5 August 2008 (aged 75) Walnut Creek, California, United States |

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | US |

| Alma mater | King's College, University of Durham (Newcastle University) |

| Known for | Creating the first noble gas compound |

| Awards | Corday–Morgan Prize (1962) Steacie Prize (1965) Elliott Cresson Medal (1968) Welch Award in Chemistry (1976) William H. Nichols Medal (1983) Davy Medal (2002) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | University of British Columbia Princeton University University of California, Berkeley |

Neil Bartlett (15 September 1932 – 5 August 2008) was a British chemist who specialized in fluorine and compounds containing fluorine, and became famous for creating the first noble gas compounds. He taught chemistry at the University of British Columbia and the University of California, Berkeley.

Biography

Neil Bartlett was born on 15 September 1932 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.[1] Bartlett's interest in chemistry dated back to an experiment at Heaton Grammar School when he was only eleven years old, in which he prepared "beautiful, well-formed" crystals by reaction of aqueous ammonia with copper sulfate.[2] He explored chemistry by constructing a makeshift lab in his parents' home using chemicals and glassware he purchased from a local supply store. He went on to attend King's College, University of Durham (which went on to become Newcastle University[3]) in the United Kingdom where he obtained a Bachelor of Science (1954) and then a doctorate (1958)[4] in the inorganic chemistry research group of Dr. P.L. Robinson.[5]

In 1958, Bartlett's career began upon being appointed a lecturer in chemistry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC, Canada where he would ultimately reach the rank of full professor.[4] During his time at the university he made his discovery that noble gases were indeed reactive enough to form bonds. He remained there until 1966, when he moved to Princeton University as a professor of chemistry and a member of the research staff at Bell Laboratories. He then went on to join the chemistry department at the University of California, Berkeley in 1969 as a professor of chemistry until his retirement in 1993. He was also a staff scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory from 1969 to 1999.[4] In 2000, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[1] He died on 5 August 2008 of a ruptured aortic aneurysm.[6] He lived with his wife Christina Bartlett until his death. They had four children.[6]

Research

Bartlett's main specialty was the chemistry of fluorine and of compounds containing fluorine. In 1962, Bartlett prepared the first noble gas compound, xenon hexafluoroplatinate,[7][8] Xe+[PtF6]−. This contradicted established models of the nature of valency, as it was believed that all noble gases were entirely inert to chemical combination. His discovery incited other chemists to discover several other fluorides of xenon:[9] XeF2, XeF4, and XeF6.[8]

Honors

In 1968 he was awarded the Elliott Cresson Medal. In 1973, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society (United Kingdom). In 1976 he received the Welch Award in Chemistry for his synthesis of chemical compounds of noble gases and the consequent opening of broad new fields of research in the inorganic chemistry. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1977.[10] In 1979, he was honored as a Foreign Associate of the National Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the prestigious Davy Medal in 2002 for his discovery that the noble gases were not that noble after all. Previous recipients of the Davy Medal had included people as diverse as Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, the inventor of the Bunsen burner, and Albert Ladenburg, who suggested the existence of the compound prismane. In 2006, his research into the reactivity of noble gases was designated jointly by the American Chemical Society and the Canadian Society for Chemistry (CSC) as an International Historic Chemical Landmark at the University of British Columbia in recognition of its significance, "fundamental to the scientific understanding of the chemical bond."[1] Bartlett was nominated for a Nobel Prize in Chemistry every year between 1963 and 1966 but did not get the Prize.[11]

Hospitalization

In January 1963, Bartlett and his graduate student, P. R. Rao, were hospitalized after an explosion in the laboratory. As they looked at what they thought might be the first crystals of XeF2, the compound exploded, getting shards of glass in the eyes of both men. According to Bartlett, he thought that the compound may have contained water molecules, and he and Rao took off their glasses to get a better look. They were both taken to the hospital for four weeks, and Bartlett was left with damaged vision in one eye. The last piece of glass from this accident was removed 27 years later.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 "Neil Bartlett and the Reactive Noble Gases". American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ↑ Jolly, William L. "Neil Bartlett, In Memoriam". Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Universities of Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne Act 1963" (PDF). Newcastle University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 Henderson, Andrea Kovacs (2009). American Men & Women of Science – 26th Edition. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale. p. 397. ISBN 978-1-4144-3301-1.

- ↑ "Biography of Neil Bartlett". College of Chemistry. University of California, Berkeley. 2006. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

Neil decided that his strengths lay with inorganic chemistry, and after his graduation with a BSc in 1954, he began research in that field, in Dr. P.L. Robinson's Inorganic Chemistry Research Group.

- 1 2 Barnes, Michael (8 December 2008). "Neil Bartlett, emeritus professor of chemistry, dies at 75". Neil Bartlett, emeritus professor of chemistry, dies at 75. UC Berkeley News. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ Bartlett, Neil (1962). "Xenon hexafluoroplatinate(V) Xe+[PtF6]−". Proceedings of the Chemical Society. 1962 (6): 218. doi:10.1039/PS9620000197.

- 1 2 Hargittai, Istvan (2009). "Neil Bartlett and the first noble-gas compound" (PDF). Structural Chemistry. 20 (December): 953–959. doi:10.1007/s11224-009-9526-9. S2CID 94962566. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ Harding, Charlie; Johnson, David Arthur; Janes, Rob (2002). Elements of the P Block, Volume 1. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 91. ISBN 0-85404-690-9. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

After Bartlett's discovery, other chemists quickly re-examined Pauling's suggestion that xenon would combine with fluorine.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ↑ https://old.nobelprize.org/nomination/archive/show_people.php?id=13013 Archived 15 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine Nobel Prize nomination database

- ↑ Ball, Philip (2015). Elegant solutions : ten beautiful experiments in chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry. Cambridge. ISBN 978-1-78262-546-9. OCLC 958129576.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Christe, Karl O. (2008). "Obituary: Neil Bartlett (1932–2008)". Nature. 455 (7210): 182. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..182C. doi:10.1038/455182a. PMID 18784717. S2CID 4416768.

External links

- "Biography of Neil Bartlett". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009.

- "MSU Gallery of Chemists' Photo-Portraits and Mini-Biographies: Neil Bartlett". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.