| |

Netherlands |

Thailand |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of the Netherlands, Bangkok | Royal Thai Embassy, The Hague |

| Envoy | |

| Remco van Wijngaarden | Chatri Archjananun |

Bilateral relations between the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Thailand date back to 1604,[1] as one of the earliest interactions between Europeans and Siamese. Thailand today is a popular tourist site for Dutch tourists, while the Netherlands is the largest EU invester in Thailand.[2] The Netherlands operates an embassy in Bangkok, as well as consulates in Chiang Mai and Phuket.[3] Thailand itself operates an embassy in the Hague, as well as consulate a in Amsterdam.

History

Origins

In 1601, Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck became the first Dutch person to land in modern-day Thailand when he landed in Pattani, which was an independent sultanate. In December 1602, Pattani was visited again by two more ships owned by the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The Dutch would later establish a comptior (trading post) in Songkhla and Pattani in 1607.[4] In 1608, King Ekathotsarot of Ayutthaya gave permission for the VOC to establish a trading post in the capital city of Ayutthaya. Siamese ambassadors were later sent to the Dutch Republic and were given an audience by the Prince of Orange, Maurice.[5] However, the posts in Songkhla and Pattani were abandoned around 1623 by the governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, Jan Pieterszoon Coen. In 1617, both countries signed a treaty. However the Dutch post at Ayutthaya proved to be unprofitable and was closed in 1622, but due to fears of losing their position in Siam, it was reopened again in 1624 before being closing again in 1629.[6]

During the early reign of King Prasat Thong, the Dutch supported Prasat against his rivals, including Japanese mercenaries led by Yamada Nagamasa, and against the Cambodians.[5] After Japan lifted its ban on foreign trade, the Dutch began making more investments into Siam and its exports of dear hides, sappanwood, and ray skins. Later in April 1633, Joost Schouten was instructed to construct a new trading post in Ayutthaya which costed about US$750,000 today and was completed in 1634 at Baan Holllanda.[7] Due to it being made of stone, the building gained high-status in Ayutthaya as stone was only used in Ayutthaya to build temples and palaces. It was constructed on the opposite side of the Chao Phraya river to the Portuguese and Japanese.[4] In 1634, the Sultanate of Pattani rebelled against Siamese rule. In return for the exclusive right to export animal skin from Siam, the Dutch promised to assist Prasat Thong with six Dutch vessels. The Siamese, however, didn't wait for the Dutch to arrive and were repelled from Pattani to Songkhla. The Dutch later arrived in Pattani after the Siamese retreat.[5]

Trade with Siam

In 1636, the Dutch established a second post at the mouth of the Chao Phraya river, on the west bank at Samut Prakan called 'Amsterdam' which operated as a wharehouse. On 10 December 1636, two Dutch VOC workers were attacked by Palace Guards at Ayutthaya. On the 11th, the two were convicted of attacking the palace of Prasat Thong's brother and were sentenced to death by elephant trampling. However, the VOC chief at Ayutthaya, Jeremias van Vliet, managed to secure their release but was forced to take responsibility for all Dutch people in Siam in the future. In 1640, the VOC established another trading post at Nakhon Sri Thammarat until its closure in 1663. It was reopened again in 1707 before being permanently abandoned in 1756.[5]

Han Chinese merchants were a major rival of the Dutch in colonial Indonesia. Han Chinese interpreters advised the local Muslim king of Jambi to go to war against the Dutch, while the Dutch attacked Chinese ships and Thai ships to stop them from trading with the Muslims in Jambi and make them trade with the Dutch in Batavia. The Chinese continued to violate the Dutch ban on trade with Jambi.[8][9] The Dutch East India Company was also angered by Thailand trading with the Jambi Sultanate and the Jambi Sultanate sending pepper and flowers as tribute to Thailand. leading to tensions between Thailand the Dutch in 1663-1664 and 1680-1685. The Dutch wanted Chinese banned from Thai junks and were angry when a Thai ambassador in Iran took out a loan from the Dutch in Surat but didn't pay it back after his ship got repaired. The 1682 Dutch invasion of Banten (Bantam) in Indonesia also raised alarms in Thailand, so the Thai King Narai courted the French to counter the Dutch.[10] Dutch East India Company attacked Zheng Zhilong's junks which were trading pepper with Jambi, but while the Dutch transferred 32 Chinese prisoners into the Dutch ship, the remaining Chinese managed to slaughter the 13 Dutch sailors on board the Chinese junk and retake the vessel. Zheng Zhilong demanded the Dutch then release the 32 Chinese in 1636.[11] Dutch East India Company blockaded Thai trade in 1664 and in 1661-1662 seized a Thai junk owned by a Persian official in Thailand. The Dutch tried to impede Thai and Chinese competition with the Dutch in the pepper trade at Jambi.[12] The Jambi Sultan temporarily jailed English merchants during violence between the Dutch and English.[13][14][15] The Thai and Jambi Sultanate angrily complained against the Dutch over Dutch attacks and attempts to impede Jambi's trade with Chinese and Thai.[16][17] Chinese junks regularly traded with Jambi, Patani, Siam and Cambodia.[18]

In 1649, the VOC forwarded a claim to the Siamese government which Prasat Thong refused to accept, which was met by Jeremais van Vielt with anger. As a result, Prasat Thong ordered the execution of every Dutch person in Siam and the Dutch at the post in Ayutthaya were arrested. In the end, Prasat Thong reversed his decision.[5] Relations continued to deteriorate when in 1662, King Narai imposed a royal monopoly over all trade in Siam, causing the Dutch to loose their monopoly over animal hides. In 1663, it was discovered that the Portuguese were violating the 1617 treaty and Narai ordered the closure of Ayutthaya.[19] By September 1663, the VOC sent three ships to blockade the Chao Phraya river and demanded the release of their men and merchandise.[20] In an attempt to improve Siam's relation with the Dutch, Narai sent an envoy to the Netherlands. Then on 21 June 1664, Pieter De Bitter sent an envoy to Siam who mananged to renewal the Dutch-Siamese treaty on 22 August 1664. As a result, the Dutch regained their monopoly over animal hides. The treaty also stated that Dutch people in Siam would be punished according to the laws of the Netherlands. However, King Narai hoped to curb Dutch influence over Siam by forming new relations with other Europeans, such as the French. The VOC post in Ayutthaya was restored in 1625. Yet in 1688, the French left Siam and the Dutch - who remained the only European power in Siam - signed a new treaty which secured their monopoly over animal hides and tin.[5]

Due to Japan's growing isolation, the importance of animal skin in Ayutthaya disappeared and also due to tin being cheaper in Palembang, the Dutch post in Nakhron Sri Thammarat was closed in 1740, and by the 1750s, Dutch trade with Siam dwindled. Furthermore, King Borommakot refused to renewal treaties with the VOC and ignored the VOC's ultimnation. But from 1752 to 1756, the post at Nakhron Sri Thammarat reopened for the Japanese market but was closed again as the VOC focused on their East Indies holdings. In 1760, the Burmese attacked Ayutthaya and plundered the VOC post, resulting in the death of one Dutchman.[20] By November 1765, the last VOC ship left Ayutthaya. When the Burmese captured Bangkok in August 1766, the VOC in Siam led by Werndlij decided to evacuate the company and its men from Siam, and in December 1766 the Burmese captured the Dutch post.[5]

World War II

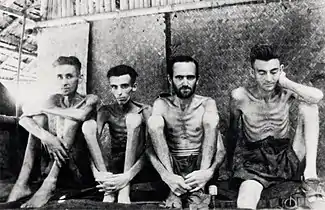

Following the Japanese invasions of Thailand and the East Indies, the Japanese began constructing the Burma Railway which were constructed by Allied POWs, including Dutch POWs. A majority of the Dutch POWs had previously been Dutch civilians or had been employed in the Royal Netherlands East Indies army. The construction of the Burma railways would result in the death of 3,000 Dutch POWs. The bodies of dead Dutchmen were later reburied in war cemeteries, such as the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery where a at least 1,896 Dutch are buried along with Australians and British dead. On May 4 every year, the Dutch anthem is played at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery before wreaths are laid on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Defence and veterans.[21]

Economy and trade

_02.jpg.webp)

The Netherlands is the largest European invester in Thailand and the 5th largest invester globally. At the end of the third quarter of 2022, direct investment from the Netherlands to Thailand was valued US$16.8 million and counted for 6.2% of all direct investment in Thailand.[22]

Thailand is also the second largest destination for Dutch merchandise being exported to ASEAN, after Singapore. The value of merchandise trade between the two was valued in 2022 at 5.7 billion euros, a 12.5% increase from 2021, while Dutch exports to Thailand grew to 1.4 billion euros, a 14.8% increase. In the Netherlands, imports from Thailand grew to 4.3 billion, 11.8% more than 2021. Thai imports of Dutch goods consisted mainly of electronic circuits, chemicals, machinery, scientific tools, dairy and animal products. In contrast, Thai exports of goods to the Netherlands were mainly computer parts, printer and telephone sets, electrical equipment, electronic circuits, poultry and rubber products. Similarly, Dutch service exports to Thailand include technical, business, professional, and transport services and the use of intellectual property. These services amounted to 569 million euros in 2022. For Thailand, services exported to the Netherlands were mainly travel, transportation, professional, and management consultant services; which together amounted to 312 million euros.[22]

The Netherlands particularly supports Thailand with agriculture and water management, with both countries being vulnerable to flooding and Climate Change.[2]

Tourism and transportation

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines currently operates direct flight routes between Amsterdam and Suvarnabhumi airport.[23] When travelling to the Netherlands, Dutch citizens do not require a visa and can stay in Thailand for 45 days.[24] Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 200,000-250,000 Dutch tourists visited Thailand.[2]

State and official visits

| Dates | People | Locations | Itinerary |

| September 6–9, 1897 | King Chulalongkorn, Prince Svasti Sobhana and Prince Svasti Mahisza | Amsterdam | Arrived as an honorary guest of Queen Wilhelmina, where they visited the Rijksmuseum and Coster Diamonds. This was a part of his tour of Europe[25] |

| October 24–27, 1960 | King Bhumibol Adulyadej and Queen Sirkit | Amsterdam, the Hague, Rotterdam | As part of their tour of Europe, the Netherlands served as the second last stop. They also attended a gala event in the Hague.[26] |

| April 28-May 2, 1980 | Princess Srindhorn and Princess Chulabhorn | Amsterdam | Represented the King and Queen of Thailand during the coronation of Queen Beatrix. |

| October 4–6, 2010 | Princess Srindhorn | Groningen, Enschede and the Hague | Came on the invitation of the University of Twente, and also visited the University of Groningen. Participated in a banquet hosted by Prince Willem-Alexander in the Hague.[27] |

| August 27–29, 2012 | Princess Srindhorn | Venlo | Visited to attend the Floriade 2012, after a previous visit to Germany.[27] |

| April 19, 2013 | Princess Srindhorn and Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn | Amsterdam | Attended the Inauguration of King Willem-Alexander, with Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn representing King Bhumibol.[28] |

| Dates | People | Locations | Itinerary |

| November 16–21, 1962 | Princess Beatrix | Bangkok, Kanchanaburi | Visited the Reclining Buddha in Bangkok, as well as war cemeteries in Kanchanaburi.[29][30] |

| August 24–26, 1971 | Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld | Bangkok | Left Amsterdam and arrived in Thailand. After their visit to Thailand, they then went to Indonesia.[31] |

| January 19–23, 2004 | Queen Beatrix and Crown Prince Willem-Alexander | Bangkok | Arrived to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Dutch-Thai relations. |

| June 12–14, 2006 | Crown Prince Willem-Alexander and Princess Maxima | Bangkok | Attended the Diamond Jubilee of King Bhumibol Adulyadej |

Resident diplomatic missions

See also

References

- ↑ Zaken, Ministerie van Algemene (2004-01-19). "Address by her Majesty the Queen of The Netherlands on the occasion of the state visit to Thailand 19 - 23 january 2004 - Toespraak - Het Koninklijk Huis". www.koninklijkhuis.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- 1 2 3 Zaken, Ministerie van Buitenlandse (2022-06-26). "Thailand: an emerging middle power in Asia - Weblogs - Government.nl". www.government.nl. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- 1 2 3 "The Royal Families". สถานเอกอัครราชทูต ณ กรุงเฮก (in Thai). Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- 1 2 "De VOCsite : homepage". www.vocsite.nl. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 W A R Wood. A History Of Siam. BRAOU, Digital Library Of India. Fisher Unwin Ltd London.

- ↑ "Van Vliet's Siam". University of Washington Press. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ↑ "08 Sep 2000 - UNEAC Asia Papers No - Archived Website". Trove. Archived from the original on 2000-09-07. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Meilink-Roelofsz, M. A. P. (2013). Asian Trade and European Influence: In the Indonesian Archipelago between 1500 and about 1630 (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 262. ISBN 94-015-2835-7.

The king of Jambi, however, could not tolerate such highhanded action by the Dutch in Jambi roads since it might lead to the downfall of trade in his kingdom. Moreover, besides Chinese junks the Dutch attacked Siamese as well, ...

- ↑ Meilink-Roelofsz, M. A. P. (2013). Asian Trade and European Influence– In the Indonesian Archipelago between 1500 and about 1630 (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 261. ISBN 94-015-2835-7.

The king of Jambi, however, could not tolerate such highhanded action by the Dutch in Jambi roads since it might lead to the downfall of trade in his kingdom. Moreover, besides Chinese junks the Dutch attacked Siamese as well, ...

- ↑ Blussé, Leonard, ed. (2020). Around and About Formosa. 元華文創. p. 303. ISBN 957-711-150-5.

while overlooking the Dutch archival materials, which in fact were more copious and detailed than any other European ... Tension between the Siamese and Dutch increased when the VOC grew suspicious of the Sultan of Jambi sending the ...

- ↑ Cheng, Weichung (2013). War, Trade and Piracy in the China Seas (1622-1683). TANAP Monographs on the History of Asian-European Interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 125. ISBN 90-04-25353-X.

The traders around the South China Sea, no matter who they were—the Siamese king, the Portuguese in Malacca and Macau, or the Fukienese merchants—all dealt in ... Consequently, as it left Jambi, Iquan's junk was seized by a Dutch ship.

- ↑ Kathirithamby-Wells, J. (1990). Kathirithamby-Wells, J.; Villiers, John (eds.). The Southeast Asian Port and Polity– Rise and Demise. Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore. p. 137. ISBN 9971-69-141-8.

The Siamese grievance in 1661-62 was the V.O.C.'s seizure of a Siamese crown junk fitted out by one of the king's Persian ... The Siamese crown maintained that it had no intention of entering into competition with the Dutch in the Jambi ...

- ↑ Calendar of state papers– 1625/29. H.M. Stationery Office. 1884. p. 150.

... and the ship's boat ; captured a Chinese junk , which was retaken by a Dutch freemen to Siam , killing two English and the junk sent to Batavia . The King of Jambi exasperated against our people , imprisoned our merchants and seized ...

- ↑ Great Britain. Public Record Office (1884). Calendar of State Papers– Preserved in the State Paper Department of Her Majesty's Record Office. Colonial series, volume 6. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 150.

Letter received from factory at Jambi to Geo . ... taking muskets , swords , provisions , and the ship's boat ; captured a Chinese junk , which was retaken by a Dutch freemen to Siam , killing two English and the junk sent to Batavia .

- ↑ Calendar of state papers: Colonial series. ... p. 62.

- ↑ Roelofsen, C.G. (1989). "Chapter 4 The Freedom of the Seas: an Asian Inspiration for Mare Liberum?". In Watkin, Thomas G. (ed.). LEGAL RECORD & HISTORICAL REALITY– Proceedings of the Eighth British Legal History Conference. A&C Black. p. 64. ISBN 1-85285-028-0.

The Dutch retaliated by the means they had used before, arresting Asian shipping, in the main Chinese junks, ... but I will maintain an open market'.68 Energetic protests by Jambi and Siam against Dutch arrests of shipping should also ...

- ↑ Roelofsen, C.G. (1989). "The sources of Mare Liberum; the contested origins of the doctrine of the freedom of the seas". In Heere, Wybo P.; Bos, Maarten (eds.). International Law and Its Sources– Liber Amicorum Maarten Bos. Brill Archive. p. 115. ISBN 90-6544-392-4.

The Dutch retaliated by the means they had used before , arresting Asian shipping , in the main Chinese junks , and unloading ... but I will maintain an open market : 7 ° Energetic protests by Jambi and Siam against Dutch arrests 67.

- ↑ Prakash, Om, ed. (2020). European Commercial Expansion in Early Modern Asia. An Expanding World: The European Impact on World History, 1450 to 1800. Routledge. ISBN 1-351-93871-1.

... Leur' estimate China sent out four junks to Batavia, four to Cambodia, three to Siam, one to Patani, one to Jambi, ... However, the Dutch established some control over the Chinese trade only after the destruction of Macassar in 1667 ...

- ↑ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : a short history. Internet Archive. Chiang Mai : Silkworm Books. ISBN 978-974-9575-44-4.

- 1 2 "Embassies of the King of Siam sent to his excellency Prince Maurits, arrived in The Hague on 10 September 1608 : an early 17th century newsletter, reporting both the visit of the first Siamese diplomatic mission to Europe and the first documented demonstration of a telescope worldwide /transcribed from the French original, translated into English and Dutch, introduced by Henk Zoomers ; and edited by Huib Zuidervaart. | Royal Museums Greenwich". www.rmg.co.uk. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ↑ Zaken, Ministerie van Buitenlandse (2022-06-15). "Dutch history in Thailand - Thailand - Netherlandsandyou.nl". www.netherlandsandyou.nl. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- 1 2 Zaken, Ministerie van Buitenlandse (2023-05-03). "Thai Economic Performance in 2022 and Outlook for 2023 - Publication - Netherlandsandyou.nl". www.netherlandsandyou.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ "From Amsterdam to Bangkok, Economy Class".

- ↑ "Traveling to Thailand from Netherlands in 2023: Passport, Visa Requirements". www.hinterlandtravel.com. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ "The Story of King Rama V". Royal Coster Diamonds. 2020-12-11. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ Saad719 (2020-10-24). "Thai State Visit to the Netherlands, 1960". The Royal Watcher. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn's Activities". sirindhorn.net. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ "HRH Crown Prince, HRH Princess Sirindhorn to visit Netherlands April 30". nationthailand. 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ "PRINCESS BEATRIX VISITS WAR CEMETERIES IN THAILAND". British Pathé. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ "THAILAND: BANGKOK: PRINCESS BEATRIX VISITS TEMPLE AND BLIND SCHOOL". British Pathé. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ Limited, Alamy. "Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard depart from Schiphol Airport for Thailand and Indonesia, August 23, 1971, queens, The Netherlands, 20th century press agency photo, news to remember, documentary, historic photography 1945-1990, visual stories, human history of the Twentieth Century, capturing moments in time Stock Photo - Alamy". www.alamy.com. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

%252C_de_hoofdstad_van_Siam_Iudea_(titel_op_object)%252C_SK-A-4477.jpg.webp)