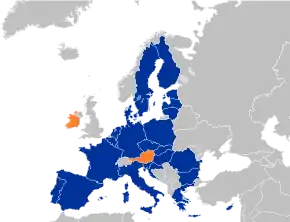

- Neutral EU member states

- Other EU member states

- Non-EU member states

The European Union (EU) is an institution of its own kind consisting of member states being part of an alliance as well as military neutral member states while developing a Common Foreign and Security Policy for the union as a whole. The military neutral member states are Austria, Ireland and Malta.[1] Previous military neutral states are Finland and Sweden.

For the military neutral states, membership in the EU and its Common Foreign and Security Policy poses a challenge for them to keep up their neutral status. This results from the obligation of the Common Foreign and Security Policy for the member states to provide it and the other member states with their solidarity as well as to stay coherent with the European foreign policy to not constrain its effectiveness.[2] Thus, the problem is to stay coherent with the Common Foreign and Security Policy while still keeping a neutral position.

Definition of Neutrality

The concept of neutrality has no universally agreed definition. Different emphasis can be put on legal, political, ideological, economic and military dimensions as well as how neutrality is executed in practice. [3] Depending on different actors, values and goals, neutrality can have different meanings.[4]

A definition focusing mainly on military aspects is based on the Hague Conventions of 1907 and offers a legal basis for neutrality in the international relations.[5] Neutrality means that a state does not participate in armed conflicts with other states to achieve security.[6] Due to neutrality,

“[n]eutral states cannot participate in wars directly or indirectly. Neither should they support or favour warring parties militarily, nor make their territory available to them, supply them with weapons or credits, or restrict private armaments exports in a one-sided way. Neutrals are also required to defend themselves against violations of their neutrality.”

— [5]

Neutrality is thus seen in the context of modern states and closely related to European military and political history.[5] This interpretation of neutrality is closely related to military non-alignment which simply means that a state is not formally joining a military organisation.[7] Austria, Finland and Sweden have slowly evolved to military non-aligned states.[8]

In addition to that, in the context of the Cold War, scholars have developed a distinction between permanent or de jure and temporary or de facto neutrality. Permanent neutrality describes neutrality which is established by binding law or a treaty. Austria's neutrality belongs to this category. Temporary neutrality refers to neutrality which is only established by the political practices of a state. The Finnish, Irish and Swedish neutrality are examples for this category.[5]

Furthermore, an active definition of neutrality bases the concept on a cosmopolitan worldview and identifies non-aggression, peace-promotion and self-determination as the motivating values behind it. This is how neutrality is often understood at the domestic level.[4] It is perceived as a moral obligation to promote international justice, law and peace as well as a commitment for restricting and regulating the use of force in international relations. Promoting these values is thus a possibility for a state to design an independent and discretionary foreign policy. [9]

Moreover, neutrality can also be seen as a strategy of smaller states to avoid being pulled into the sphere of influence of a larger state and to keep as much autonomy as possible.[1]

Case studies

Austria

Pre-accession

The Austrian neutrality has its roots in the outcomes of the World War II. Austria was occupied by the four victorious powers and with the beginning of the Cold War the negotiations on an Austrian State Treaty did not achieve much progress. By committing itself to permanent neutrality, the Austrian government could overcome this deadlock. Therefore, a "Federal Constitutional Law on the Neutrality of Austria" was adopted in 1955 stating that Austria permanently stays neutral and will never join military alliances nor allow other countries to establish military bases on their territory.[10]

Initially, the neutral status was perceived as a political sacrifice so that Austria could become sovereign and independent again. During the 1950s, the Austrian foreign policy became more independent from the victorious powers and since the early 1960s Austria took part in United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operations, Vienna became home for several international organisations and a few important meetings and conferences took place there.[11] In the 1970s with a changed government, Austria further developed its relations with Eastern European states. It contributed with a lot of effort to the international community and cooperated actively in international organisations, especially in the UN. As a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council from 1973 to 1974, Austria could strengthen its international profile. Moreover, own initiatives outside the multilateral framework aimed at building bridges and focused mainly on the North-South conflict, the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians and the détente between West and East. This marks a time of Austria pursuing an active understanding of neutrality.[11]

With rising tensions in the East-West conflict again at the end of the 1970s, the conditions for active neutrality worsened and with a new government in 1983, the Austrian foreign policy was refocused. International issues lost importance while the European continent and especially the European Community became more central. But neutrality, although now more focused on the European sphere, constrained Austria's possibilities to participate in the European integration.[11]

Changes in the concept of neutrality through membership in the EU

Until a new government was formed in 1987, membership in the European Community was seen as incompatible with Austrian neutrality. The new government was in favour of integrating the Austrian economy completely into the European Single Market and promoted thus the accession of Austria into the European Community.[12] The application for membership in the European Community was submitted by the Austrian government in 1989 with an additional clause protecting Austrian neutrality. An abolishment of neutrality was not negotiable with the argument that Austria would otherwise lose its reliability which was built upon being a neutral state for decades.[13]

The end of the Cold War changed this. Some Austrian politicians saw neutrality as outlived and took a "revisionist" approach towards it.[14] But there was a lot of scepticism towards the Austrian membership application in the European Community. The European Commission was concerned about the compatibility of a future Common Foreign and Security Policy with the permanently neutral status of Austria. Assurances from Austria were needed guaranteeing that it would comply with the future Common Foreign and Security Policy. Austria assured its full and active participation in the Common Foreign and Security Policy as well as its solidarity. In the perspective of the governing parties, it was expected that the European Community would play a key role in the development of a new collective European security system. As a result, Austria’s treaty of accession from 1994 had no longer a formal clause regarding Austrian neutrality.[14] Instead the Federal Constitutional Law on the Neutrality of Austria was amended so that Austria would be able to participate in economic sanctions as a result of the Common Foreign and Security Policy.[14]

With a new government in 1996, Austria was not only allowing the realisation of a common defence policy, but it also confirmed its active participation in it. Furthermore, more legislative changes were carried out allowing Austria to send troops as part of military operations in the framework of more institutional organisations than only the UN and to participate to full extend in the Petersberg tasks.[15] Although having a constructive abstention introduced through the Treaty of Amsterdam, Austria was not obliged to stay neutral in conflicts anymore.[16] With a new government coalition formed by the ÖVP and the FPÖ in 2000, the concept of neutrality was for the first time questioned officially. It was seen as being contradictory to European solidarity. But from 2003 on, after the astonishment of other neutral states, the Austrian government supported neutrality again.[17] The eventual participation of Austria in the battle groups, initiated in 2004,[18] is a further example for Austria's reduced definition of neutrality resembling more a military non-alignment than the former active neutrality.

Ireland

Pre-accession

The Anglo-Irish Treaty entering into force in 1922 created Ireland as an independent state and determined it as a neutral state. This also did not change with the new Constitution of Ireland in 1937 and in an Anglo-Irish defence agreement in 1938 it was assured that Ireland would not be used as a base for foreign states to attack the United Kingdom. Neutrality during the Second World War was a sign for Irish sovereignty and independence.[19] With a focus on Irish cultural and social values and an antipathy towards power politics and military participation, Ireland developed a strong isolationism and did therefore not participate at the first stages of European integration.[20] When Frank Aiken became foreign minister in 1957, Ireland’s participation in multilateral fora, especially in the Council of Europe and the UN, increased. Ireland developed a high policy profile regarding disarmament, anti-colonial issues and participation in the United Nations peacekeeping operations.[20] This tends as well more towards an active understanding of neutrality.

Changes in the concept of neutrality through membership in the EU

Ireland applied for a first time unsuccessfully for membership of the European Community in 1961 together with the United Kingdom.[10] While the prime minister was considering possible military implications of the membership and did not exclude the possibility of joining NATO, the parliament and the population were not in agreement with abandoning neutrality.[21] The second successful application in 1967 was then stressing the separation of the European Community and NATO. Moreover, the Irish government developed a "defence last" position which would only agree to defence cooperation as a result of political cooperation of European member states after economic integration would have been completely achieved.[21] Other than that, the issue of neutrality was avoided supported by the fact, that the European Political Cooperation created in 1970 excluded defence and security from foreign policy and that the European Community was more designed as a "civilian power".[21] With the tensions of the Cold War rising again in the 1980s, neutrality became an important topic again and Ireland created a national declaration of neutrality in the wake of the ratification of the Single European Act in 1987 protecting its status as militarily neutral state.[22]

At the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s, Ireland got back to the "defence last" position and followed a more revisionist approach on neutrality and its compatibility with European Political Co-operation. The latter had also the impact that the Irish government was more developing its position in the context of the positions of the other member states. Furthermore, Ireland changed its Defence Act of 1960 to participate in a UN peace enforcing mission in 1991. This was a fundamental change in policy.[23] Although getting an "Irish clause" in the Maastricht Treaty protecting neutrality, Ireland accepted its overall objectives including defence. More public debate was provoked by the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1996 about the inclusion of the Petersberg tasks where the Irish government was reluctant regarding participation in tasks of combat forces.[24] For the participation of Irish troop in the European Rapid Operational Force the Irish government developed a "triple lock" system where military operations must have a UN mandate, must be approved by the House of Representatives and must be agreed on by the government.[25]

Moreover, the Treaty of Nice was rejected in a first referendum because of the fear of too much militarisation of the EU threatening Irish neutrality, but it passed a second one after a declaration of the member states on respect for Irish neutrality and a constitutional ban on being involved in a common European defence arrangement.[26] This position was maintained in following treaty negotiations, but the Treaty of Lisbon nevertheless included a mutual defence clause. This led to another failed referendum which was successfully repeated after assuring again that the EU would not interfere with Ireland's neutrality.[27] In general, when requiring a referendum for treaty changes the Irish government argued for respect for the specific nature of its security and defence policy although its concept of neutrality became more and more loose over time.[27]

Formerly neutral states

Finland

Pre-accession

Finland did not claim neutrality immediately after the Second World War. In the years directly following the war, it followed a strategy of appeasing the Soviet Union and of accepting Soviet security interests in Finland. Joint security arrangements and a Soviet naval base on Finnish territory signified this. The withdrawal from that naval base in 1956 gave Finland its sovereignty back and enabled it to join the UN shortly followed by the initial articulation of a neutral policy. The consolidated sovereignty and the neutrality were seen as positive results from the Finnish post-war foreign and security policy which had the establishment of mutual trust with the Soviet Union as goal.[28] The neutrality of Finland was a process that came to maturity with the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe in 1975 consolidating the meaning of neutrality and achieved its recognition by the Soviet Union in 1989.[29] From the Finnish perspective, the European Community was perceived as an economic organisation and thus loose relations with it were acceptable. But complete membership was seen as not compatible with neutrality.[30] Neutrality was also a result of Finland's geopolitical situation in a peripheral location with limited capabilities. Self-help was the only reliable solution in form of a cautious foreign and security policy. But it was thus in a good position to ease tensions between the superpowers and to build mutual trust among them.[31] The emerging cooperation in the field of foreign policy within the European Community was in 1990 still seen as a threat to Finland’s neutrality and therefore also to its sovereignty and independence.[32]

Changes in the concept of neutrality through membership in the EU

When joining the EU, Finland stopped being a neutral state. While staying militarily non-aligned, it aligned politically, economically and culturally with Western Europe. Cultural connections with Nordic and Western European countries had already been emphasised in the post-war period, but the political and economic integration of Finland only gained momentum after the end of the Cold War.[33] Finland's decision to apply for membership in the EU in 1992 is often perceived as a sudden and profound change in its post-war foreign policy.[34] Moreover, security and identity have surprisingly been the major factors for joining the EU and not economic reasons.[34] In order to fully comply with the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the EU, the Finnish government redefined neutrality as military non-alignment and independent defence.[34] The EU served Finland as a new way to guarantee its security, to pursue Finnish interests and to express Finnish sovereignty.[35]

Former Finnish Prime Minister, Matti Vanhanen, on 5 July 2006, stated that Finland was no longer neutral:

"Mr Pflüger described Finland as neutral. I must correct him on that: Finland is a member of the EU. We were at one time a politically neutral country, during the time of the Iron Curtain. Now we are a member of the Union, part of this community of values, which has a common policy and, moreover, a common foreign policy."[36]

However, Finnish Prime Minister Juha Sipilä on 5 December 2017 still described the country as "militarily non-aligned" and that it should remain so.[37]

Russia's attack on Ukraine in February 2022 has led to a re-evaluation of neutrality and of Finnish NATO membership,[38] and Finland became a full member of NATO in April 2023.[39]

Sweden

Pre-accession

The beginning of Sweden's neutrality can be found somewhere in between the seventeenth and nineteenth century.[40] During the post-war period, economic reasons were favouring Swedish membership in the European Community while the neutrality to which the population became attached was an obstacle. The government realised the incompatibility of neutrality and membership and terminated formal negotiations in 1971.[41]

Changes in the concept of neutrality through membership in the EU

The end of the Cold War changed the external conditions. Without an opportunity to fulfil an intermediary role and regarding the economic disadvantages from being outside of the European Single Market, Swedish politics changed in favour of EU membership while assuring that neutrality could be kept in the long term based on the assumption that the European Community would not develop in the direction of a common defence very soon.[42] As a result, Sweden applied in 1991 without any references to neutrality. When questioned about the ability to maintain neutrality, the government emphasised the military non-alignment as the core of neutrality.[43] Swedish neutrality with its shift to military non-alignment was seen as being adjusted to the changing international environment.[44] Russia’s invasion in Ukraine caused Sweden to apply for NATO membership in 2022, and thus Sweden is no longer considered a military non-aligned state.[45]

See also

References

- 1 2 Alecu de Flers 2009, p. 302.

- ↑ Algieri, Franco (2010). Die Gemeinsame Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik der EU (in German). Wien: Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG. p. 49.

- ↑ Devine 2011, p. 335.

- 1 2 Devine 2011, p. 337

- 1 2 3 4 Jokela 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ Radoman 2021, p. 3.

- ↑ Agius 2011, p. 385.

- ↑ Agius 2011, p. 371.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, p. 304.

- 1 2 Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 32

- 1 2 3 Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 33

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2012, pp. 94f.

- 1 2 3 Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 95.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 96.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2012, pp. 97f..

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 98.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, pp. 30f..

- 1 2 Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 31

- 1 2 3 Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 63

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, p. 64.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, pp. 64f..

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, p. 65.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, p. 66.

- ↑ Alecu de Flers 2009, pp. 66ff..

- 1 2 Alecu de Flers 2012, p. 67.

- ↑ Jokela 2011, p. 48.

- ↑ Jokela 2011, pp. 48f..

- ↑ Jokela 2011, p. 50.

- ↑ Jokela 2011, pp. 55f..

- ↑ Jokela 2011, pp. 57f..

- ↑ Jokela 2011, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 Jokela 2011, p. 59

- ↑ Jokela 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ Presentation of the programme of the Finnish presidency (debate) 5 July 2006, European Parliament Strasbourg

- ↑ "Finland should stay militarily non-aligned: prime minister". Reuters. 4 December 2017.

- ↑ "HS:n tiedot: Suomen Nato-hakemuspäätös tehdään toukokuun puolenvälin jälkeen". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ NATO. "Finland joins NATO as 31st Ally". NATO. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ↑ Radoman 2021, pp. 103ff..

- ↑ Radoman 2021, p. 138.

- ↑ Radoman 2021, pp. 138f..

- ↑ Radoman 2021, pp. 139f..

- ↑ Radoman 2021, p. 140.

- ↑ Waterfield, Bruno (2022-04-11). "Finland and Sweden set to join Nato as soon as summer". The Times. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

Bibliography

- Agius, Christine (2011). "Transformed beyond recognition? The politics of post-neutrality". Cooperation and Conflict. 46 (3): 370–395. doi:10.1177/0010836711416960. S2CID 144737157.

- Alecu de Flers, Nicole (2009). A 'Militarisation' of the EU? The EU as a global actor and neutral member states. in: Laursen, Finn: The EU as a Foreign and Security Policy Actor, Dordrecht: Republic of Letters Publishing BV.

- Alecu de Flers, Nicole (2012). EU Foreign Policy and the Europeanization of Neutral States. Comparing Irish and Austrian foreign policy. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

- Devine, Karen (2011). "Neutrality and the development of the European Union's common security and defence policy: Compatible or competing?". Cooperation and Conflict. 46. doi:10.1177/0010836711416958. S2CID 143565150.

- Jokela, Juha (2011). Europeanization and Foreign Policy. State identity in Finland and Britain. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

- Radoman, Jelena (2021). Military Neutrality of Small States in the Twenty-First Century. The Security Strategies of Serbia and Sweden. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.