New Birmingham | |

|---|---|

| |

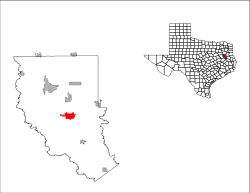

New Birmingham Location within the state of Texas | |

| Coordinates: 31°46′25″N 95°7′15″W / 31.77361°N 95.12083°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Cherokee |

New Birmingham is an abandoned town site in central Cherokee County, Texas, United States, now a ghost town. New Birmingham once seemed destined to be a major industrial mecca in the heart of east Texas. Lying just off U.S. Highway 69, the site was approximately two miles southeast of the county seat of Rusk.

Beginnings

Conceived in 1887, New Birmingham was the brainchild of Anderson Blevins, a sewing machine salesman originally from Alabama. Traveling through east Texas, he became aware of copious deposits of iron ore in the area of Rusk, Texas, and having familiarity with Birmingham in his home state, was struck with the possibility of a similar industrial mecca in east Texas.[1] Discovering that some small-scale iron processing was already occurring at Rusk Penitentiary,[2] he approached his brother-in-law, W. H. Hamman, who enthusiastically supported the venture. Hamman was an attorney, an ex-Confederate General and a wealthy, well-established oil-man.[3] Together, they brought in a number of local investors, formed a company to develop the idea and began taking options on ore-laden acreage. Venture capital was also raised from H. H. Wibirt of New York and Richard Coleman of St. Louis, and by 1888 the company, under the name of Cherokee Land & Iron Company,[4] was purchasing land suitable for mining. Eventually, some 20,000 acres had been acquired and construction of a smelting plant to develop the ore was begun.[5]

Two 50-ton furnaces—one called the "Tassie Belle" after Blevins' wife, the other called "Star and Crescent"—were constructed and quickly went into production.[6] Additional capital from St. Louis and New York allowed the firm to reorganize as the New Birmingham Iron and Land Company. Anderson Blevins was on the Board of Directors; H.H. Wibirt of New York and Richard Coleman served as president and vice-president, respectively. (The company would undergo another reorganization and name-change in 1890, becoming the New Birmingham Iron and Development Co.)

Meanwhile, a pipe works and brick kiln were constructed and a coal-fired electric generating plant promised the utmost in modern convenience for new residents.[7]

"Iron Queen of the Southwest"

In September 1889, the town of New Birmingham was incorporated. Banks, a railway depot, a schoolhouse, a weekly newspaper, an ice plant and electricity from a coal-fired plant—all these created an impression not only of great potential, but of an established community. And then, there was the Southern Hotel, a palatial structure described as follows by Hattie Joplin Roach in her History of Cherokee County:

The Southern Hotel, which the promoting company erected at a cost of more than $60,000 was the center of New Birmingham's gay life. Its first register, beginning March 28, 1889, and closing Feb. 9, 1890, recorded guests from twenty-eight states, including Jay Gould of railroad fame and Grover Cleveland, recently come from the presidential chair, Robert A. Van Wyck, financiers, who had risked their millions in the attempted development of Cherokee County's iron ore were frequently registered. Along with the millionaires were citizens from nearby towns come for thrill as well as business, and newspaper representatives sent for copy. On one day there were guests from eight states.[8]

In its prospectus issued in October 1891, the company stated:

On Nov. 12, 1888, New Birmingham had not a single house completed. It was entirely in the woods. Today, with nearly 400 buildings completed and occupied, she claims and justly so, a population of 1,500. The streets are graded, and houses and streets lighted with electricity; the business houses are the best class of brick buildings; it boasts a street railway and a magnificent hotel, the Southern, with all modern improvements. The industries represented today are two blast furnaces, a pipe foundry, planing mill, sash and door factory, steam laundry, and steam bakery and other industries being negotiated for.[9]

To all appearances, the "Iron Queen", as she had been dubbed by her promoters, seemed poised to rule.[10]

Demise

As if to suggest that successful cities are those which emerge naturally as need dictates, rather than from the visions of speculators and promoters, New Birmingham was destined to fold back into the pine forest from which it emerged and become the distant memory it is today. In the 1890s, two circumstances converged to doom the aspirations of the New Birmingham planners.

Capital

A shortage of capital led the management of the company to seek investment from the British sources; the promotion there was met with considerable interest and, indeed, members of a British investment syndicate, the Baring Brothers, traveled to Texas to evaluate the potential at New Birmingham. Favorably impressed with the development at New Birmingham, they were all the more encouraged by the abundance of resources available so near the operations. In short order, they had committed to infuse the venture with upwards of $1,000,000.[11]

Legalities and politics intruded to bar this solution. The "Alien Land Law of Texas" flatly barred these potential investors from having any interest in a company whose assets were in the soil of Texas. Recently put into effect, ostensibly, to protect ranchers in West Texas from land speculation by wealthy foreign investors, the statute had been promoted by Governor James Hogg. Hogg was, himself, a native of Rusk and Cherokee County. The management of NBI&D lobbied the governor to support an amendment to the law, but if he ever considered a move to assist the people of his home county, there was little evidence of it. In spite of being wined, dined and otherwise feted throughout New Birmingham and the Southern Hotel, Hogg stood firmly against any moderation of the Alien Land Law.

Calamity

Then the Panic of 1893 overtook the country, collapsing markets across the board. Lack of demand for pig iron led to a shutdown of the plants and without the jobs that had brought them there, people began to drift out of New Birmingham. An explosion seriously damaged the Tassie Belle furnace and further complicated matters, but had economic conditions been better, that might have been merely a temporary setback.

Curse

The fall of New Birmingham was not without apocryphal blame. For years, some citizens of the fading mecca attached their troubles to a curse placed on the town by a bereaved widow. On July 14, 1890,[12] General W. H. Hamman had been gunned down in the streets of the town by an enraged husband seeking to avenge imagined insults directed at his wife, either by Hamman or his wife. S. T. Cooney, the shooter, was arrested, tried, found guilty and sent to prison for manslaughter. If in her view that was not sufficient penalty for the loss of her husband, Mrs. Hamman's exasperation came to full boil when in 1892, Mr. Cooney was pardoned. In a fit of outrage and grief, Mrs. Hamman (with some irony the sister of Tassie Belle Blevins)[13] took to the streets beseeching the Almighty to destroy the city and have it swallowed by the forest from whence it had come.[14]

Apocryphal, almost certainly. The greater damage to the future of New Birmingham was the death of W. H. Hamman, whose money, influence and business acumen had been instrumental from the beginning. But in any case, by the end of the year the town was virtually abandoned.

Slide into oblivion

New Birmingham languished. The nearly 400 homes there, boarded up and empty, begin to fall into disrepair or were dismantled, as were storefronts in the business district. But before it entirely disappeared, some attempts were made to resurrect the town and its industry. In 1899, the Record Brothers contemplated construction of a new smelter, but nothing came of it. Loath to relinquish his dream, Anderson Blevins attempted to reopen the foundry in 1907, but nothing came of that. As luck would have it, there was the Panic of 1907. By 1910, the last actual resident had moved out of the town and during World War I the ironworks and many remaining buildings were scrapped. The Southern Hotel remained, occupied only by a maintenance man, but in 1926, otherwise vacant for 33 years, it was consumed by flame. In 1932, the New Birmingham school was razed to make way for U.S. Highway 69 running south of Rusk.

An historical marker was erected at the site of New Birmingham in 1966. Tassie Belle Historical Park contains vestigial ruins of that furnace.

Notes and references

- ↑ King, Dick (1953). Ghost Towns of Texas. The Naylor Company. p. 74.

Impressed with the outcroppings of ore he saw throughout the countryside, he had a vision that a second Birmingham might sprout on the spot;

- ↑ Rusk Penitentiary

- ↑ "Guide to the William Harrison Hamman Papers, 1828-1966". Retrieved January 1, 2013.

Although his means were reduced by the war, in 1866 Hamman became the first oil prospector in Texas; he drilled his first oil well at Saratoga in Hardin County. [...] In August 1870 Hamman helped to incorporate three business enterprises - the Calvert Bridge Company, to build "a safe and substantial bridge" over the Brazos River at Calvert; the Pacific and Great Eastern Railway Company of Texas, to build a rail link between the Red River and the Rio Grande; and the Texas Timber and Prairie Railroad Company, to build a railroad between Beaumont and Bremond. In May of that year he also helped charter the Calvert and Belton Railroad. In 1871 Hamman moved to Calvert when the Houston and Texas Central Railroad reached town. There he established a successful legal practice.

- ↑ Baker, T. Lindsey (1986). Ghost Towns of Texas. Norman, OK: The University of Oklahoma Press. p. 104.

Blevins then traveled east, secured the backing of capitalists there and, with them, formed the Cherokee Land and Iron Company.

- ↑ King, Dick (1953). Ghost Towns of Texas. San Antonio, TX: The Naylor Company. p. 74.

As soon as the company had purchased twenty thousand acres of land in Cherokee County, it went to work to make arrangements for mining and smelting operations.

- ↑ Baker, T. Lindsey (1986). Ghost Towns of Texas. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 107.

By 1891, New Birmingham had an estimated 1,500 inhabitants, two iron furnaces ... an iron pipe foundry, a large brick kiln and other industrial enterprises.

- ↑ Baker, T. Lindsey (1986). Ghost Towns of Texas. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 107.

By 1891, New Birmingham had an estimated 1,500 inhabitants, two iron furnaces ... an iron pipe foundry, a large brick kiln and other industrial enterprises.

- ↑ King, p.74

- ↑ King, p. 75

- ↑ Bill Cannon, Texas. Land of Legend and Lore, 2004, ISBN 1556229496, p.19

- ↑ Kombos, Thanasis. "When Time Was Young and Life a Thing Devine: New Birmingham, Texas". Jacksonville Progress. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Guide to the William Harrison Hamman Papers, 1828-1966". pp. Correspondence, etc. re: W.H. Hamman's death (includes letters of condolence and material re: Cooney trial) 1890. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

.

- ↑ "Descendants of Nathaniel Gist" (PDF). Retrieved December 7, 2012.

p. 57: Children of George Lawdermilk and Elizabeth Loughridge: iii. Tassie Bell Lawdermilk, iv. Ella Virginia Lawdermilk, b. 1851; p. 124: Tassie Bell Lawdermilk, born about 1850 in Mississippi. She married Anderson Bean Blevins; p. 127: Ella Virginia Lawdermilk, born 14 Jun 1851... She married William Harrison Hamman.

- ↑ Kombos, Thanasis. "When Time Was Young and Life a Thing Devine: New Birmingham, Texas". Jacksonville Progress. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

External links

- Baker, Lindsey T. (1986). "Ghost Towns of Texas". Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - King, Dick (1953). "Ghost Towns of Texas". San Antonio, TX: The Naylor Company.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Long, Christopher (2009). "New Birmingham, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online.

- Kombos, Thanasis (2010). "When Time Was Young and Life a Thing Devine: New Birmingham, Texas". Jacksonville Progress. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- Roach, Hattie Joplin (1934). "A History of Cherokee County". Dallas, TX: Southwest Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)