| African Burial Ground National Monument | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | 290 Broadway, New York, NY 10007 |

| Coordinates | 40°42′52″N 74°00′16″W / 40.71444°N 74.00444°W |

| Area | 0.35 acres (0.14 ha)[1] |

| Created | February 27, 2006 |

| Visitors | 108,585 (in 2011)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | African Burial Ground National Monument |

| Designated | April 19, 1993 |

| Reference no. | 93001597[3] |

| Architects | Rodney Léon and Nicole Hollant Denis |

| Designated | February 27, 2006 |

African Burial Ground National Monument is a monument at Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way (Elk Street) in the Civic Center section of Lower Manhattan, New York City. Its main building is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway.[4] The site contains the remains of more than 419 Africans buried during the late 17th and 18th centuries in a portion of what was the largest colonial-era cemetery for people of African descent, some free, most enslaved.[5] Historians estimate there may have been as many as 10,000[6]–20,000 burials in what was called the Negroes Burial Ground in the 18th century. The five to six acre site's excavation and study was called "the most important historic urban archaeological project in the United States."[7] The Burial Ground site is New York's earliest known African-American cemetery; studies show an estimated 15,000 African American people were buried here.[8]

The discovery highlighted the forgotten history of enslaved Africans in colonial and federal New York City, who were integral to its development. By the American Revolutionary War, they constituted nearly a quarter of the population in the city. New York had the second-largest number of enslaved Africans in the nation after Charleston, South Carolina. Scholars and African-American civic activists joined to publicize the importance of the site and lobby for its preservation. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993 and a national monument in 2006 by President George W. Bush.

In 2003 Congress appropriated funds for a memorial at the site and directed redesign of the federal courthouse to allow for this. A design competition attracted more than 60 proposals. The memorial was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the role of Africans and African Americans in colonial and federal New York City, and in United States history. Several pieces of public art were also commissioned for the site. A visitor center opened in 2010 to provide interpretation of the site and African-American history in New York.

Africans and African Americans in New York City

Pre-Revolutionary War

Slavery in the New York City area was introduced by the Dutch West India Company in New Netherland in about 1626 with the arrival of Paul D'Angola, Simon Congo, Lewis Guinea, Jan Guinea, Ascento Angola, and six other men. Their names denote their place of origin- Angola, the Congo, and Guinea. Two years after their arrival three female Angolan slaves arrived. These two groups heralded the beginning of slavery in what would become New York City, and which would continue for two hundred years.[9] The first slave auction in the city took place in 1655 at Pearl Street and Wall Street – then on the East River. Although the Dutch imported Africans as slaves, it was possible for some to gain freedom or "half-freedom" during the time of Dutch rule. In 1643, Paul D'Angola and his companions petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom. Their request was granted, resulting in their acquisition of land on which to build their own houses and farm. By the mid-17th century, farms of free blacks covered 130 acres where Washington Square Park later appeared.[10] Enslaved Africans in chattel bondage were granted certain rights and afforded protections such as the prohibition against arbitrary physical punishment – for example, whipping.

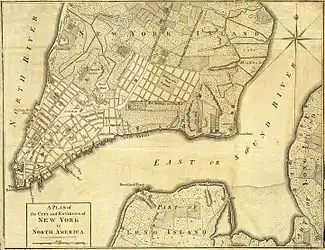

The English seized New Amsterdam in 1664, and renamed the fledgling settlement to New York (after the Duke of York). The new city administration changed the rules governing slavery in the colony. At the time of the seizure, some forty percent of the small population of New Amsterdam were enslaved Africans.[12] The new rules[13] regarding slavery were more restrictive than those of the Dutch, and rescinded many of the former rights and protections of enslaved residents, such as the prohibition against arbitrary physical punishment. In 1697 Trinity Church gained control of the burial grounds in the city and passed an ordinance excluding blacks from the right to be buried in churchyards. When Trinity took control of the municipal burial ground, now its northern graveyard, it barred Africans from interment within the city limits.[12] Through much of the 18th century, the African burying ground was beyond the northern boundary of the city, which was just beyond what is today Chambers Street.

As the city population increased, so did the number of residents who held slaves. "In 1703, 42 percent of New York's households had slaves, much more than Philadelphia and Boston combined."[14] Most slaveholding households had only a few slaves, used primarily for domestic work. By the 1740s, 20 percent of the population of New York were slaves,[15] totaling about 2,500 people.[10] Enslaved residents also worked as skilled artisans and craftsmen associated with shipping, construction, and other trades, as well as laborers. By 1775, New York City had the largest number of enslaved residents of any settlement in the Thirteen Colonies excepted Charles Town, South Carolina, and had the highest proportion of Africans to Europeans of any settlement in the Northern colonies.[12]

Post-Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War, the British occupied New York City in the summer of 1776 and they maintained control of the city until the Peace of Paris was signed and they departed on November 25, 1783, a date which came to be known as Evacuation Day. As in the rest of the Thirteen Colonies, the Crown had offered freedom to enslaved peoples who escaped from their Patriot masters and fled to British lines. 3,000 of these individuals were eventually listed in the Book of Negroes. This promise of freedom attracted thousands of slaves to the city who had escaped to British lines. In 1781 the New York legislature offered a financial incentive to Loyalist slaveowners who assigned their slaves to military service, and promised freedom at the war's end for the slaves.

By 1780 the African-American community swelled to about 10,000 in New York City, which became the center of free blacks in North America.[15] Among those who escaped to New York were Deborah Squash and her husband Harvey, who fled from George Washington's plantation in Virginia.[15] After the end of the war, according to provisions concerning property in the Treaty of Paris, the Americans demanded the return of all former slaves who had escaped to British lines. The British steadfastly refused the American request and evacuated 3,000 freedmen with their troops in 1783 for resettlement in Nova Scotia, other British colonies, and England. Instead of returning the slaves which had been promised their freedom, the British came to an agreement with the Americans to financially recompensate them for each slave lost.[15] Other freedmen scattered from the city to evade slave catchers.

Aided by individual manumissions after war's end, by 1790 about one-third of the blacks in the city were free.[10] The total city population was 33,131, according to the first national census.[16]

In 1799 the state legislature passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery with little opposition. Similar to Pennsylvania's law, it provided for gradual manumission of slaves. Children born to slave mothers after July 4, 1799, were considered legally free, but had to serve as indentured servants to their mother's master, until age 28 for men and 25 for women, before gaining social freedom. Until reaching age 21, they were considered the property of the mother's master. All slaves already in bondage before July 4, 1799, remained slaves for life, although they were reclassified as "indentured servants."[14][15][17]

In 1817, the New York legislature granted freedom to all children born to slaves after July 4, 1799, under the Gradual Emancipation Act,[18] with total abolition of slavery to take effect on July 4, 1827. July 4 is now known as New York's Emancipation Day, more than 10,000 slaves were freed in New York State with no financial compensation to their former owners. Blacks paraded in New York City to celebrate.

Under the 1777 New York constitution, all free men had to satisfy a property requirement to vote, which eliminated poorer men from voting, both blacks and whites.[17] A new constitution in 1821 eliminated the property requirement for white men, but kept it for blacks, effectively continuing to disfranchise them. This lasted until passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870.[17]

The early history of free blacks and slaves in New York City became overshadowed by the waves of mid- to late nineteenth century immigration from Europe, which dramatically expanded the population and added to the ethnic diversity. In addition, most of the ancestors of today's African-American population in the city arrived from the South in the Great Migration of the first half of the twentieth century. In a rapidly changing city, the early colonial and federal history of African Americans was lost.

Site history

Negros Burial Ground

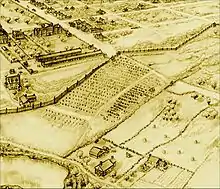

The burial ground in use for New York Town residents in the late 1600s was located at what is now the north graveyard of Trinity Church (of the Anglican / Church of England – today the Episcopal Church U.S.A.). The public burial ground was open to all for a fee, including to enslaved Africans. Some burials of deceased slaves were made just south of the public burial ground to avoid the fee. The stockade in this area ran northeast from the present-day corner of Broadway and Chambers Street to Foley Square; the wide street on the top right (southwest) is Broadway.

After Trinity was established as a parish church in 1697, the vestryman of the church began taking control of land in Lower Manhattan, including existing public burial grounds. When Trinity purchased the land at Wall Street and Broadway for the construction of their church, they passed a resolution on October 25, 1697:

That after the Expiration of four weeks from the dates hereof no Negro's be buried within the bounds & Limitts of the Church Yard of Trinity Church, that is to say, in the rear of the present burying place & that no person or Negro whatsoever, do presume after the terme above Limitted to break up any ground for the burying of his Negro, as they will answer it at their perill & that this order be forthwith publish'd.

The "rear of the present burying place" did not include the town cemetery (now the north churchyard). The church petitioned for control of this burial ground, which was granted by the colonial Province of New York on April 22, 1703.

This prohibition against the burial of those of African descent necessitated finding another area acceptable to the colonial authorities. What would become the "Negro's Burial Ground" was located on what was then the outskirts of the developed town, just north of present-day Chambers Street and west of the former Collect Pond (later Five Points). The area was part of a land grant issued to Cornelius van Borsum on behalf of his wife Sara Roelofs (1624–1693) for her services as an interpreter between the town of New York and the various Native American tribes in the area, such as the Lenape and Wappinger. The land would remain part of her estate until the late 1790s when the grade was raised with landfill in anticipation of development, and the land subdivided into building lots.

Labelled on old maps as the "Negros Burial Ground", the 6.6-acre area was first recorded as being used around 1712 for the burials of enslaved and freed people of African descent. The first burials may date from the late 1690s after Trinity barred African burials in the former city cemetery. The area of the burial ground was in a shallow valley surrounded by low hills on the east, south and west, which enveloped the southern shore of Collect Pond and the Little Collect. The burial ground was outside the stockade marking the northern boundary of the city. The stockade in this area ran northeast from the present-day corner of Broadway and Chambers Street to Foley Square after it had expanded northward, similar in form and function to the former stockade on Wall Street. The revelation that physicians and medical students were illegally digging up bodies for dissection from this burial ground precipitated the 1788 Doctors' Riot.

Development

After the city closed the cemetery in 1794, the area was platted for development. The grade of the land was raised with up to 25 feet (7.6 metres) of landfill at the lowest points covering the cemetery, thus preserving the burials and the original grade level. As urban development took place over the fill, the burial ground was largely forgotten. Washington Hall, a hotel and banquet hall was built on a portion of the site from 1809-1812. The first large-scale development on the land was the construction of the A.T. Stewart Company Store, the country's first department store; it opened in 1846 at the corner of 280 Broadway and Chambers Street, replacing Washington Hall. Several skeletons were unearthed during the commencement of building the store.[20]

The site's earliest discovery in the early 19th century seems to have aroused little interest. According to an article in The New York Tribune, homeowner James Gemmel, who owned a house at 290 Broadway in the early 19th century, told an unnamed daughter that when the cellar for their house was being dug many human bones were found. He assumed that he had discovered a potter's field.[21] In 1897, when the building at 290 Broadway was demolished to make way for the R. G. Dun and Company Building (later financial firm of Dun & Bradstreet), workers in excavating found a large number of human bones.[22] Some concluded at that time that these were connected to a 1741 incident in which thirteen African Americans were burned at the stake and eighteen were hanged,[21] however others wondered whether the bones were of Dutch or Indian origin.[20][23] Many bones were taken as souvenirs by so-called relic hunters.[20][23]

Discovery of site and controversy

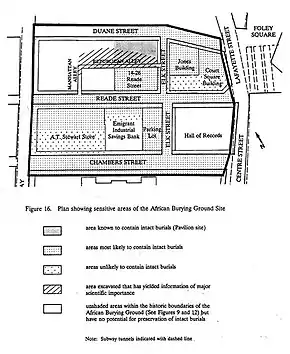

On October 8, 1991, the federal General Services Administration (GSA) announced the discovery of 8 intact burials during an archaeological survey and excavation (which had started in May 1991[24]) for the construction of a new $275 million federal office building planned at 290 Broadway between Reade and Duane streets.[25][26] The building was to be later known as the Ted Weiss Federal Building, named for deceased U.S. Representative Ted Weiss from New York. Under section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act,[27] the federal government is required to identify and assess the historic presence of a site prior to building on the land. The agency had done an environmental impact statement (EIS) prior to purchase of the site, but the archaeological survey had predicted that human remains would not be found because of the long history of urban development in that area.[12]

After the discovery of the first intact burials became publicly known, the African-American community became very concerned. With the pressure of construction costs, GSA tried to continue excavation and construction on the site. The community believed it was not being sufficiently consulted and that respect was not being given to the nature of the discoveries. They believed that the burial findings required a better archaeological project design for protection and study of the remains.[12]

Protests

Initially, GSA had planned full archaeological retrieval of the remains as full mitigation of the effects of its construction project on the burial ground. Within the year, its teams removed the remains of 419[28] persons from the site, but it had become clear that the extent of the burial ground was too large to be fully excavated. In 1992, activists staged a protest at the site about GSA's handling of the burial issue, especially when it was found that some intact burials were broken up during construction excavation at part of the site.[12] GSA halted construction until the site could be thoroughly assessed. It provided additional funding to conduct a further archaeological excavation to reveal any other bodies on the site and to assess the remains.[12] Located between New York City Hall and the federal courts, the site had symbolic value. "The 'invisibility' of Black history in New York City partially accounts for the importance of the Foley Square site"; activists hoped to find a means there to redress "the injustice and the imbalance of the historic record, and to give voice to the silenced ones".[12]

Although archaeologists studied the site and the remains for almost a dozen years, critics of the construction project believed GSA's original archaeological research design was inadequate, as it did not require a plan for the treatment of uncovered remains.[12] In addition, the African-descendant community in New York City was not consulted in the development of the research design, nor were any archaeologists who had experience studying the African diaspora, although GSA had distributed the EIS to more than 200 state and local agencies and stakeholders, many recommended by the city.[12] In the early stages of the project, national GSA officials and related Congressional committees directed that excavation and construction proceed.[12]

Oversight of the project increased by stakeholders, such as the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and community activists. After continued protests from a coalition of community members, politicians, and scholars, in 1992 the House Subcommittee on Public Works held budget hearings for GSA in New York, at which it heard testimony from a wide variety of critics of GSA's handling of the project and also heard from the GSA Administrator.[12] Several changes occurred. Control of the burial site was transferred from an archaeological firm in the city to the physical anthropologist Michael Blakey and his team at Howard University, a historically black college in Washington, D.C., for study at the Montague Cobb Biological Anthropology Laboratory. This ensured that African-American students would participate in studies of their ethnic ancestors' remains.[12]

Effects of protests

In large part due to activism by the African-American community, the United States Congress passed, and on October 6, 1992, President George H. W. Bush signed, HR 5488 "The Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government Appropriations Act" (which became Public Law 102-393) which ordered the GSA to immediately cease construction, archeological excavation & skeletal exhumation on the pavilion portion of the Ted Weiss Federal Building (where the remains had been found) and to appropriate $3 million to modify the pavilion foundation, prevent further deterioration of the burial ground & memorialize the site. The southern portion of the building, slated to be built on the parcel by Duane and Elk Streets, was eliminated to provide adequate room for a memorial.[12]

In addition, activists lobbied for landmark status for the burial ground, and gathered 100,000 signatures to send to the U.S. Department of the Interior. On April 19, 1993, 0.34 acre of the African Burial Ground was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (#93001597) and became a National Historic Landmark. Given its importance, GSA proposed partial mitigation of the adverse effects to the burial ground of the construction of 290 Broadway, by undertaking programs of data analysis, curation, and education.[30] There was also growing support for a museum on the site to interpret African-American experience and history in New York. The discovery and long controversy received national media attention, raising interest and awareness in public archaeology projects. Theresa Singleton, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution said,

The media exposure has created a larger, national audience for this type of research. I've been called by dozens of scholars and laypeople, all of them interested in African-American archaeology, all of them curious about why they don't know more about the field. Until recently, even some black scholars considered African-American archaeology a waste of time. That's changed now.[12]

Government and private developers learned about the need to "include descendant communities in their salvage excavations, especially when human remains are concerned."[12] The findings at the burial ground already had highlighted some of the losses of slavery, as African Americans had not been recently recognized as a major part of early New York history until then. As the journalist Edward Rothstein wrote, "Among the scars left by the heritage of slavery, one of the greatest is an absence: where are the memorials, cemeteries, architectural structures or sturdy sanctuaries that typically provide the ground for a people’s memory?"[10]

Site studies

_pg773_THE_WASHINGTON_TRUST_COMPANY%252C_STEWART_BUILDING%252C_280_BROADWAY.jpg.webp)

In total, the intact remains of 419 men, women and children of African descent were found at the site, where they had been buried individually in wooden boxes. There were no mass burials. Nearly half were children under 12, indicating the high mortality rate of the time. Historians and anthropologists estimate that over the decades, as many as 15,000–20,000 Africans were buried in Lower Manhattan. They have determined that this was the largest colonial-era cemetery for enslaved African people. It is also "possibly the largest and earliest collection of American colonial remains of any ethnic group."[12] Some of the burials included items related to African origins and burial practices.

The work of excavation and study of the remains was considered the "most important historic urban archaeological project undertaken in the United States."[7] These remains stand for the estimated tens of thousands of persons at the burial ground and historically in New York, representing Africans' "critical" role in "the formation and development of this city and, by extension, the Nation."[31][32][33]

As a result of public engagement, the Howard University team identified four questions which the community hoped to have answered from studies of the remains:

- "cultural background and origins of the burial population;

- the cultural and biological transformations from African to African-American identities;

- quality of life brought about by enslavement in the Americas; and

- modes of resistance to enslavement."[34]

Before the erection of the monument, the burial ground had endured an immense amount of abuse. Archeologists found a substantial amount of industrial waste and ceramics while excavating the site.[35] Archaeologists concluded that burial ground was being used as a dumpsite by Europeans during the 18th century. The burial ground was also subject to grave robbing and looting during this time. In April 1788, the Doctor Riot spread throughout New York City. The riots were led by physicians that would steal corpses from graves to study them as the supply of medical corpses was extremely low. Many of these stolen corpses came from the African Burial Ground. There was speculation that the grounds were not only being looted but were overcrowding due to the burial of unclaimed bodies in the place of the stolen remains.

Some bodies had items buried with them, as part of personal and cultural rituals. An example is the silver pendant shown at right. Some heads showed filed teeth, an African ritual decoration. Howard University did forensic studies, assessing the remains for nutrition, diseases and indicators of general living conditions for African slaves and free blacks.

After the Howard University studies were completed, the 419 skeletons were placed in the Ancestral Reinterment Grove here on October 4, 2003, in a ceremony including the "Rites of Ancestral Return". They were placed in hand-carved wooden coffins made in Ghana & lined with Kente cloth, which were placed in 7 sacrophagi & buried in 7 burial mounds with the heads facing west.[36] The "commemorative ceremony was inclusive and international in scope, and was organized by GSA and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture" of the New York Public Library.[36] This emotional memorial stretched over multiple cities including Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark, and finally Manhattan. Thousands attended the reinterment and commemoration.[36]

Memorial

Construction and dedication

GSA ran a design competition for the site memorial in consultation with stakeholders and community activists, attracting over 60 proposals. The winning memorial design, by Rodney Leon and Nicole Hollant-Denis,[37] was selected in April 2005.[38] The cultural landscape architect for the memorial was Elizabeth Kennedy Landscape Architects.[39]

The memorial consists of two components: the 24-foot (7.3 m) tall Ancestral Chamber and the large Circle of the Diaspora. The height of the Ancestral Chamber represents the depth of the discovered graves. The Ancestral Chamber is made from Verde Fontaine green granite from Africa and its engraved heart-shaped Sankifa symbol from West Africa means "Learn from the past to prepare for the future". The Circle of the Diaspora features a map of the Atlantic area in reference to the Middle Passage,[40] by which slaves were transported from Africa to North America. It is built of stone from Africa and North America, to symbolize the two worlds coming together.[41] The Door of Return, refers to "The Door of No Return", a name given to slave ports set up for involvement with the age-old local institution of slavery on the coast of West Africa, from which so many people were transported after sale by their native chiefs, never to see their homeland again. The memorial is designed to reconnect ethnic African Americans to their ancestors' origins.[41]

On February 27, 2006, President George W. Bush signed a proclamation designating the burial site as the 123rd National Monument.[42] The federal government also announced plans for a $8 million memorial at the site.[43] The Burial Grounds was transferred to the operating jurisdiction of the National Park Service as its 390th unit. The memorial was dedicated on October 5, 2007, in a ceremony presided over by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and poet Maya Angelou.[41][44] As part of the dedication ceremonies, the city officially renamed Elk Street as African Burial Ground Way.[45]

In 2016, Dan Hoeg, CEO of The Hoeg Corporation, tendered a $34.3 million offer and development proposal to purchase 22 Reade Street and the Burial Grounds to the City of New York. The African-American bidding group was led by Dan Hoeg, CEO of the African American owned development firm The Hoeg Corporation; Burial Ground Monument architect, Rodney Leon; and Davide Bizzi, CEO of Italian development company, Bizzi & Partners Development.[46]

Visitor Center

On February 27, 2010, a visitor center for the African Burial Ground National Monument opened in the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway, which was built over part of the archaeological site.[10] The visitor center includes a permanent exhibit, "Reclaiming Our History," on the significance of the burial site. Created by Amaze Design, it features a life-sized tableau by StudioEIS depicting a dual funeral for an adult and child. Other parts of the exhibit explore the work-life of Africans in early New York and connection to national history, as well as the late 20th-century community success in preserving the burial ground. The visitor center includes a 40-person theater and a shop. The NPS runs the visitor center and arranges for various cultural exhibitions and events at the site throughout the year.[10]

Legacy

In addition to earning several historic-landmark designations for the site, the discoveries of the African Burial Ground have changed thinking about early African-American history in New York and the nation. Many new books have been published on this topic. In 2005 the New-York Historical Society mounted its first exhibit ever on slavery in New York;[15] the planned six-month run was extended into 2007 because of its popularity.

When the visitor center at the burial ground opened in 2010, Edward Rothstein wrote,

A revision in popular understanding has taken place about slavery's history in New York City, evident in several recent books and an impressive series of shows at the New-York Historical Society. In the 18th century slaves may have constituted a quarter of the New York workforce, making this city one of the colonies' largest slave-holding urban centers.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 18, 2012. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ "African Burial Ground National Park Service". Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ "African Burial Ground National Monument". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Gale - Product Login". Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- 1 2 African Burial Ground Archived November 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, General Services Administration. Retrieved February 10, 2012

- ↑ "African burial Museum". Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ Northrup, Ansel Judd (1900). "Ansel Judd Northrup: Slavery in New York: a historical sketch. p.247". Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rothstein, Edward (February 26, 2010). "A Burial Ground and Its Dead Are Given Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Freeman Hunt: The Merchants' Magazine and Commercial Review Archived December 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Volume 27; p. 166 (1852)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Spencer P.M. Harrington, "Bones and Bureaucrats" Archived February 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Archaeology, March/April 1993. Retrieved February 11, 2012

- ↑ Obregón, Liliana (April 7, 2005), "Slave Laws in Colonial Spanish America", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.43389, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1, archived from the original on August 20, 2022, retrieved November 22, 2020

- 1 2 "The Hidden History of Slavery in New York". The Nation. Archived from the original on May 30, 2006. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

In 1991 excavators for a new federal office building in Manhattan unearthed the remains of more than 400 Africans stacked in wooden boxes sixteen to twenty-eight feet below street level.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Exhibit: Slavery in New York, 7 October 2005 – 26 March 2006". New-York Historical Society. 2005. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ↑ Campbell Gibson, "Population of the 24 Urban Places: 1790" Archived January 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, POPULATION OF THE 100 LARGEST CITIES AND OTHER URBAN PLACES IN THE UNITED STATES: 1790 TO 1990, US Census Bureau, June 15, 1998, February 12, 2012

- 1 2 3 "African American Voting Rights" Archived November 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Archives. Retrieved February 11, 2012

- ↑ D McDowell, Evelyn (July 26, 2020). "Ending Slavery—The Use of State Tax Transfers in New Jersey's Gradual Abolition Act 1804–1811". doi:10.26226/morressier.5f0c7d3058e581e69b05cf65. S2CID 242146241. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Mary L. Booth, History of the City of New York, pg. 363, W. R. C. Clark & Meeker, New York 1859

- 1 2 3 "Skeletons in Broadway Gruesome Find in a Building Excavation". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. June 27, 1897. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- 1 2 "The Old Gemmel House". New York Tribune. New York. July 25, 1897. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Dug Up Human Bones Ghastly Find of Workmen Excavating at Broadway and Reade Street, New York". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. June 27, 1897. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- 1 2 "Several Skulls Found Argument Held as to Whether They Were Indians or Dutch". The New York Times. New York. June 27, 1897. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, Kenneth R. (August 9, 1991). "Rotten Apple Dig unearths depths of depravity in buried N.Y. slum". p. 1. ProQuest 283199588.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (October 9, 1991). "Dig Unearths Early Black Burial Ground". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ↑ "New York Federal Buildings". U.S. General Services Administration. U.S. Government. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Section 106: National Historic Preservation Act of 1966". gsa.gov. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ "African Burial Ground Honored as National Monument | GSA". Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ↑ "Unearthed" (PDF). African Burial Ground National Monument. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 24, 2012.

- ↑ ABG Final Report, Archaeology, Chapter 1, p. 6

- ↑ "African Burial Ground". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 14, 2007. Archived from the original on October 29, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

The more than 400 individuals whose remains have been recovered from this site represent a much larger population whose role in the formation and development of this city and, by extension, the Nation, is critical.

- ↑ Jean Howson and Gale Harris (November 9, 1992). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: African Burial Ground". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration: African Burial Ground—Accompanying 11 photos from 1992". National Park Service. November 8, 1992. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Final Reports: Archaeology Report" (PDF). African Burial Ground. General Services Administration. 1: 6. February 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ↑ U.S. General Services Administration. "The New York African Burial Ground: unearthing the African Presence in colonial New York". vol. 1, 2009, p. 371, https://www.nps.gov/afbg/learn/historyculture/upload/downVol1-Part1-The-Skeletal-Biology-of-the-NYAGB.pdf Accessed November 10, 2020

- 1 2 3 "Reinterment". African Burial Ground. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ Boyd, Herb (February 7, 2019). "BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2019: Ancestors at rest in Manhattan's historic African Burial Ground". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ↑ Confessore, Nicholas (April 30, 2005). "Design Is Picked for African Burial Ground Memorial, and Heckling Begins". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ↑ "African Burial Ground National Monument | The Cultural Landscape Foundation". tclf.org. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ↑ "Rodney Leon Tapped to Design National Historic Landmark; Winner to Create Memorial for 17th, 18th-Century Africans". Exodus News. May 6, 2005. Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "New York opens slave burial site". BBC News. October 6, 2007. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

The late 18th Century burial site was gradually built over as New York expanded, but was rediscovered during an excavation in 1991. Some 400 remains, many of children, were found during excavations; half of the remains found at the burial site were of children under the age of 12.

- ↑ "National Monuments Numbered". National Park Service. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ↑ Ramirez, Anthony (March 6, 2006). "Site of African Burial Ground Gets Recognition, and Money". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ↑ Lopez, Elias E. (October 2, 2007). "Nameless Are Memorialized at Old African Burial Site". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ↑ "African Burial Ground Memorial Opening Events". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. October 1, 2007. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ↑ "City Building to Get Residential Makeover". Tribeca Citizen. September 5, 2016. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

Further reading

- Blakey, M.L. 1997. The New York African Burial Ground Project: an examination of enslaved lives, a construction of ancestral ties, Briefing prepared for the Sub-commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities Commission on Human Rights, United Nations. Delivered at the Palais des Nations, Geneva Switzerland, August 19.

- Blakely, M.L. 1996. "Howard University research reaches a new plateau," Newsletter of the African Burial Ground and Five Points Archaeological Project, 1 (10):3–7.

- Epperson, T.W. 1997. "The politics of "race" and cultural identity at the African Burial Ground excavations, New York City," World Archaeological Bulletin, 7:108–117.

- Foote, T.W., M. Carey, J. Giesenberg-Haag, J. Grey, K. McKoy, and C. Todd. 1993. "Report on Site-Specific History of Block 154," Written for the African Burial Ground Research Project. New York.

- Gathercole, P. and D. Lowenthal, eds. 1994. The Politics of the Past, New York: Routledge.

- Gero, J. and M.W. Conkey. 1993a. Engendering Archaeology: Women and Prehistory, Basil Blackwell.

- Gero, J. and M.W. Conkey. 1993b. "Tensions, pluralities and engendering archaeology," In Gero, J. and M.W. Coney, ed. Engendering Archaeology: Women and Prehistory, pp. 3–31. Basil Blackwell.

- Howson, J.E. 1992. "The Foley Square Project: An 18th century cemetery in New York City," African American Archaeology, Newsletter No. 6, Spring. pp. 3–4.

- Jaffe, S.H. 1995. " 'This Infernal Traffic': New York Port and the illegal slave trade." Seaport: New York's History Magazine 29 (3):36–37.

- Jamieson, R.W. 1995. "Material culture and social death: African-American burial practices," Historical Archaeology, 29 (4):39–58.

- Jill Lepore, New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan (Knopf, 2005), about the 1741 slave revolt

- Perry, W. and R. Paynter. "Epilogue: Artifacts, Ethnicity and the Archaeology of African Americans," In Singleton, T., ed. We Too Are America: Essays in African American Archaeology, Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

- Satchel, M. 1997. "Only remember us: skeletons of slaves from a New York grave bear witness," U.S. News and World Report, July 28:51 and 54.

- Singleton, T.A. 1995. "The Archaeology of Slavery in North America," in Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 24, pp. 119–140.

- Taylor, R. 1992. "Land of the blacks," Newsday (New York), February 6, 1992, p. 60.

- Thompson, R.F. 1983. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, New York: Vintage.

- White, S. 1988. "We dwell in safety and pursue our honest callings: free blacks in New York City, 1783–1810," The Journal of American History, 75 (2):445–470.

- Will, G. 1991. "Salvage archaeology in Manhattan offers a perspective about America," Hartford Courant.

- Wilson, S. 1996. Citations on the New York African Burial Ground 1991–1996, (3rd Ed.) Compiled by the Office of Public Education and Interpretation of the African Burial Ground. New York City.

External links

- African Burial Ground National Monument – Official NPS website

- Final Reports – Electronic versions of the final reports for the African Burial Ground project

- African Burial Ground, Visitor information and walking tour, New York Harbor & Parks

- African Burial Ground Archived February 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Website, General Services Administration

- MAAP: Mapping the African American Past, Columbia University

- African Burial Ground National Monument presidential proclamation

- Announcement of National Monument proclamation, National Park Service