The New Zealand Federation of Labour, also known as The Red Federation and The United Federation of Labour, was a New Zealand federation of syndicalist trade unions which was formalised in 1909.[1] The federation is best known for its involvement in the nation-wide Great Strike of 1913 which almost brought New Zealand's economy to a halt. The Federation's members were often referred to as 'Red Feds'.

History

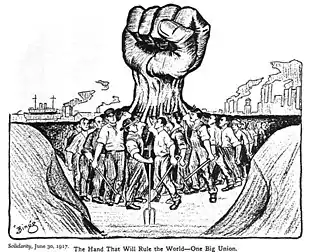

The federation was originally formed as the New Zealand Federation of Miners in 1908 after a strike of coal miners in Greymouth. The strike was largely in opposition to an arbitration act by government which meant that industrial disputes had to be settled in a special court. In 1909 the federation was renamed to the New Zealand Federation of Labour. The Federation was inspired by American union federations including the Industrial Workers of the World.

Prominent leaders included Bob Semple who in 1935 became Minister of Public Works with the first Labour Government.

The federation was ambivalent towards Jewish refugees of Nazi persecution. In the event of refugees being given refuge in New Zealand, they preferred that the country accept non-Jewish victims of fascism.[2]

1913 General Strike

In 1913, the Federation played a leading role in nation-wide strike action which almost escalated into a general strike. This industrial action followed a dispute in Wellington where waterside workers demanded better pay, and another dispute in Huntly. The strikes were ultimately defeated in 1914 by scab workers and strike-breaking police.

The Federation was defeated during the Great Strike. Many prominent leaders of the federation, and other socialist organisations, went on to form the New Zealand Labour Party in 1916.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Roth, Herbert. ""Red" Federation of Labour". Te Ara.

- ↑ THE RESPONSE OF THE NEW ZEALAND GOVERNMENT TO JEWISH REFUGEES AND HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS, 1933-1948 New Zealand Holocaust Centre. 2013

- ↑ Olssen, Erik (1987). "The Origins of the Labour Party: A Reconsideration" (PDF). The New Zealand Journal of History. 21 (1): 79–96.