| Ngalami | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangi of Siha (Kibongoto), Kilimanjaro | |||||

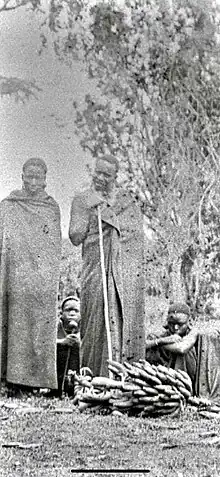

Only known photo of Ngalami | |||||

| Reign | c.1880s – 02 March 1900 | ||||

| Predecessor | Siaya of Siha | ||||

| Successor | Sinare of Siha | ||||

| Born | c.1865 Siha District, Kilimanjaro Region | ||||

| Died | March 2, 1900 Moshi District, Kilimanjaro Region. | ||||

| Burial | Unknown Unburied, his remains never found | ||||

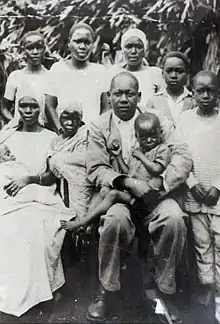

| Issue (among others) |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Mmari | ||||

| Religion | Traditional African religions | ||||

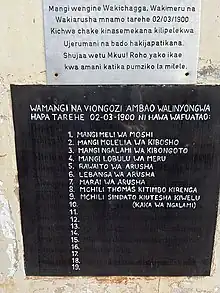

Ngalami or Ngalami Mmari (c. 1865 – 2 March 1900), also known as (Mangi Ngalami of Siha), (Mangi Ngalami in Kichagga), (Mfalme Ngalami, in Swahili) was one of many kings of the Chagga. He was the king of one of the Chagga states, namely; the Siha Kingdom in what is now modern Siha District of Tanzania's Kilimanjaro Region from the 1880s to 1900. Mangi means king in Kichagga.[1][2] Ngalami ruled from the Siha seat of Komboko (Kibong'oto) in the 1880s to 1900 when he was executed in Moshi by the Germans alongside 19 other Chagga, Meru and Arusha leaders. The execution of 19 noblemen and leaders on Friday 2nd of March 1900, included noblemen Thomas Kitimbo Kirenga, Sindato Kiutesha Kiwelu, King Meli of Moshi, King Lolbulu of Meru, King Rawaito of Arusha, King Marai of Arusha, and King Molelia of Kibosho.[3][4][5]

Origins

According to oral history, The Mmari clan say that Lakanna Mmari, their earliest paternal ancestor in recollection, travelled down to Siha in the 18th century (six generations ago from the 1960s when the clan was interviewd by author Kathleen Stahl) from the Ushira plateau on Mount Kilimanjaro. He was a farmer, a warrior, and a honey hunter. On his patch of land in Siha, he produced millet, beans, and bananas. As a warrior, his kin from the Mmari clan was tasked with leading cattle raids against their adversaries. The Nkini clan created the Siha people's sacred fire, the Kileos were furrow surveyors, the Masake (Masaki) were the first to plant the seeds in the long rains, and the Munoo (Munuo) were the first to plant the seeds during the short rains. Wasuru,the blacksmiths, were barred from marrying anyone from another clan and from having anything in common with anyone from another tribe.[6]

Saiye was the first Mmari king, and he lived in Siha's Komboko Village (currently Nasai ward). The kingdom also goes by the current as of 1961's name Kibongoto, which the first European immigrants who arrived there mispronounced Komboko. Although Kibongoto is the name used now in administrative records and maps, Siha is still the only name ever used on the mountain.[7]

Saiye was abducted as a little boy by the Arusha during one of their raids in Komboko. He was reared by them, who taught him military tactics and helped him become a good fighter. He persuaded the elders that he could teach the Siha how to repel the Arusha. He showed them how to construct defence trenches around the area to deflect any attackers.[8]

The Arusha, as was customary during war, sent news that they were going to raid Siha. Saiye told the warriors to paint their shields and dress like Maasai, much like the Arusha. He urged them to let the Arusha advance all the way into the trenches and not to assault until he gave the signal by killing an Arusha himself. As a result, the Arusha were enticed inside the circular entrenchment that had been built around each settlement. They were perplexed when Siaye gave the order to attack because they couldn't distinguish who was who. In the trenches, they were pursued and slain. At the time, the spears in use in Siha were short, with the spearhead no wider than one hand's span.[9]

He then led them on their first raid, as Sihans had never gone on a raid before, and they successfully raided the nearby Masama kingdom. Mang'aro, Mangi Ndesserua of Machame's brother, persuaded Saiye to usurp his brother and assume authority. Saiye provided him with a home in Mrau village. Saiye launched two eastward incursions. On the first, he crossed the Lawate (Liwate) River and proceeded as far as the Namwi River (the centre of the kingdom of Masama), returning with a large number of animals. He moved deeper on the second raid, accompanied by Mang'aro, crossing the enormous riverine of Kikafu River into the Machame kingdom. Ndesserua had told his soldiers to wait until Saiye and all the men were across before attacking. They were encircled, with no way out, and were all slaughtered save for a handful who managed to rush down to the plain, turn west, and climb the mountainside to Siha. This battle is named after Siaye, who was killed. Ngalami will be his successor.[10]

Rise to power

Because only old men remained after Siaye's death, the kingdom was thrown into anarchy. Clan elders dominated parts of the country for a time before electing Mangi Ngalami of the Mmari clan. He was Saiye's cousin, the same age, and also lived in Komboko. At first, he dominated the entire country except for Samake village, which included Komboko, Mrau, Wanri, and Mae, as well as probably the two upper villages adjacent to Samake, namely Maene and Kichicha (Kishisha), the remaining region of Sumu being sparsely populated. Ngalami was to govern for an long period of time.[11]

By allowing for events in his reign that occurred prior to the arrival of the first German commanders, who arrived after the reported defeat of Kibosho by German troops in 1891, the beginning of his reign can be dated to some time during the 1880s (perhaps, but less likely, as early as the 1870s). He ruled until he was hanged together with the other kings of Kilimanjaro and Meru by German authorities in 1900, giving him an unbroken reign of at least ten years. At times, his power was unquestioned.[11]

More often than not, he ruled only a portion of Siha, albeit the largest portion, while in old Samake and, in one case, Wanri, a slew of unique characters rose and fell, each exerting for a little period of time the independent powers of mangi. The continuity of Ngalami's reign brings the time together. It is the second of three phases that have characterised the Siha's history since the mid-nineteenth century.[11]

The people of Samake picked Lilio of the Orio clan to rule over them when Ngalami was first chosen. The first Arabs arrived in Siha while control was split between the two mangis. They came from the northwest, in the direction of Ngare Nairobi, and set up camp just west of the Sanya River in the plain, near the post office, in 1964. They had weapons, beads, cloth, iron wire, needles, and lead bracelets with them. The Siha people traded ivory and slaves with them. Further camps were established east of the Sanya in Komboko near the market centre in 1964, as well as higher up in the middle of old Samake.[11]

Before the Arabs arrived, there had been a severe famine in Maasailand, causing Maasai women and children to flee to Siha. The Siha people sold them as slaves to the Arabs. Subsequently, the two mangis sold their own people to the Arabs, establishing their authority by trading individuals from opposing Siha villages for weaponry. The Arabs were accompanied by the first white man to visit Siha on their second visit. As the people of old Samake saw the foreigners approaching, they gathered up the boards they used to bridge the protective trench that surrounded Lilio's land.[12]

The white man's askaris blew trumpets. The people were scared, so they changed the planks so that they could enter. The white man inquired about the mangi. Lilio had gone into hiding. In his place, his kinsman, the former mangi Kirema, appeared. The white man persisted, and Lilio ultimately emerged. Gifts were exchanged, but the white man did not reveal the reason for his visit.[12]

After three days, his caravan descended and camped in Wanri, then descended and descended into Kibosho. At the time, the Siha had never heard of a white man on Kilimanjaro, which was an intriguing side note because they had close relationships with people on east Kilimanjaro in Usseri but not with their much closer neighbours, the Machame across the Kikafu River. Otherwise, they would have known of Johannes Rebmann's visit to Machame thirty years before, in 1848–49, and von der Decken's visit in 1861.[13]

Lilio's reign came to an end with his murder. In Wanri, he assassinated a nobleman (Njama in Kichagga) of the Mwandri Clan. To avenge his father's death, this man's son Nkunde took the high trail around the back of the mountain to seek help from his blood brother Kinabo in Mkuu in present-day Rombo. When he returned, he enlisted the assistance of Kyuu in Masama and murdered Lilio. Lilio belonged to the same clan as Kibosho's royal family, the Orio Clan. Mangi Sina, one of Kilimanjaro's titans, was there at the height of his extremely lengthy reign. People from Kibosho arrived on the day of Lilio's death, taking Lilio's son Maimbe back to Kibosho with his leading men.[13]

Mangi Ngalami quickly seized the small chiefdom of Samake, while Nkunde established himself as mangi of Wanri. Other people moved down to Wanri to join Nkunde because he was a valiant warrior who was well-regarded. The 1890s began with the rule of these two Mangis, Nkunde governing Wanri and Ngalami ruling the rest of Siha from Komboko. The dating is known since the first Germans arrived during the rule of these two mangis, after they beat mangi Sina of Kibosho in the recorded fight in 1891.[11]

The Germans arrived in Siha sometime around 1891. They were headed by Funde, a Swahili man who had previously visited Siha with the Arabs. The Germans were well received by the two mangis, both when their authority was limited and later when it was established; for those who had gone to Kibosho with Lilio's son Maimbe took part in the battle when Kibosho was conquered by the Germans and on their return told the Siha people to take warning and give no resistance when the Germans finally came.[13]

Meanwhile, despite German domination, Mangi Sina of Kibosho tried to avenge the murder of his kinsman, Lilio. Receiving poison from Funde, a German intelligence agent ordered to keep him under watch. He gave it to mangi Shangali of Machame with the request that mangi Nkunde of Wanri be dispatched. Shangali delegated the poisoning to Mantiri of Nguni (now part of Masama). Nkunde became unwell. Sina requested that Shangali deliver Nkunde to him in Kibosho. On the way, Nkunde stopped in Machame and asked Shangali to look after his son Mwandi Simeon. He continued on under escort, but was beheaded before reaching Kibosho.[13]

Simeon and his mother stayed with Shangali in Machame until Simeon reached the age of marriage and married the daughter of the leader of the Shangali clan's rival branch, Ngamini, before returning to Siha. Ngalami filled the void left by Nkunde's death. He was the absolute ruler of Siha. Meanwhile, mangi Sina dispatched Lilio's son Maimbe back, who took control of old Samake. After a short time, Maimbe set out to seek assistance from Kinabo in Mkuu in order to maintain his authority, but he was reputedly killed by a lion when he arrived in Kamanga. He passed away around the end of the 1890s.[13]

Sinare's arrival would signal the greatest political power Siha had ever known, as he would become mangi not only of old Samake but of all of Siha within a year. This was going to be a busy year for him in the last year of the nineteenth century. There was no time to install him as mangi of Samake before he was summoned by the German authority to fight the Arusha in Arusha, as were all the other mangis of Kilimanjaro; upon his return, he was installed in Samake, and immediately afterwards mangi Ngalami was hanged by the Germans, and Sinare stepped into his shoes.[14]

Arrest and execution

In the first stage, it is unclear if Sinare's ascension to power in old Samake was the result of entirely internal conspiracies or of outside influence in the form of support from Machame, with whose royal house Sinare was married. The situation was evident in terms of the higher price that followed, the kingship of all Siha. Siha, a distant mountain region far from the big political centres of power, was sucked into the central whirlpool, a pawn in a large political game.[15]

There were plausible reasons given for Ngalami's downfall: he was on bad terms with an Arab named Mohammed, who lived in Komboko and informed the German authorities against him; he rejected to allocate rice supplied during a famine, saying (as any Chagga then would) that his people would not eat worms; he had been lashed by a German officer for needing a clash with Nkunde of Wanri; it was reported to the Germans that he was conspiring with the Maasai to overthrown the Germans; a well-known charge that was lightly employed across Kilimanjaro as one of the most convenient and simple ways to get rid of a rival.[14]

The real explanation was that Ngalami's fate and Sinare's succession had been decided on the battlefield at Arusha. Mangi Marealle the direct descendant to Thomas Marealle of Marangu, who was then enjoying the highest favors of the German government and was at the pinnacle of his authority, orchestrated the successful maneuver that brought down his biggest opponents on Kilimanjaro.[16]

There, he and his accomplice, young Mangi Shangali of Machame, befriended Sinare and arranged for him to be Mangi of Siha. Sinare was a minor player in the broader scheme, and it's possible that he owed this sympathetic attention to the objectives of his friendship with Shangali.[14]

When the Germans learned of Ngalami's alleged treason on the battlefield, Sinare was ordered to capture him as soon as he returned to Samake. And one day at midday, he dispatched his men to Ngalami's house in Komboko. They apprehended him and transported him to the location of the mission, with the people of Komboko joining them and vowing to fight for him. Ngalami and one of his brothers were subsequently brought across the mountain to Moshi, where they were hanged alongside many other Kilimanjaro kings and noblemen. Including Meli of Moshi, Moleila of Kibosho and Ngalami's brother. They were hanged by German military commander Kurt Johannes on 2 March 1900.The German colonial government ordered the removal of his head after dying, and it is thought that Felix von Luschan sent it to Berlin for phrenological research.[17][3]

Two days later, Shangali dispatched his men to assist Sinare in maintaining order in Siha. Marealle and Shangali's confidant, Funde arrived. He and Shangali's men were there at the installation. Sinare thus became Siha's Mangi.[14]

Outside influence was responsible for Sinare's accession. The prospects of a member of his clan wresting the chieftainship from the then-dominant clan at such a late point, with German power fully established, were slim. Sinare got in by the skin of his teeth, though. The Mmari clan currently held the most sway and had served as Siha's rulers for Ngalami and Saiye before him. In Samake alone, the Orio clan had intermittently provided a succession of rulers, including Kirema, Maletua, Lilio, and Maimbe. On the other hand, Sinare's Kileo clan had a long lineage that went back to its lone ruling figure, Mmdusio. The assertions of the Orio clan appeared to be more compelling than those of Kileo when seen in the context of old Samake alone.[15]

Ngalami's passing marked the end of a chapter in Siha's history. He was the final leader selected by the Siha people and the one who, up to that point, could most nearly claim to have united all of Siha under his dominion. Since Sinare's arrival, their political fates in the 20th century have been largely moulded by outside forces as a result of the big political game played on Kilimanjaro.[16]

After Ngalami’s death

From 1900 until 1905, Sinare was the ruler of Siha. He ruled from Old Samake, which was perched high in the northwestern corner of the kingdom. This was a wise move since it benefited his supporters, but it was extremely problematic from an administrative standpoint. In 1905, Maanya, a relative of Ngalami, served as one of his advisors. By filing a complaint against him with the German authorities, Sinare colluded against him. From Machame, the Germans dispatched askaris to detain Maanya. The Askaris shot his wife as he was hiding. He eventually emerged from hiding and was transported to prison, where he passed away.[16]

Shortly after, Maanya's brother Naruru, invited Sinare to his home for a drink as retaliation for his brother's death. The drink that was meant for Sinare had been secretly poisoned by Naruru and his wife. Naruru had another man give the wine to Sinare because his wife was afraid to do it herself. The man declined Sinare's request to take a sip of the beverage. He then instructed Naruru to take a sip, which was done. Then Sinare drank. Both passed away.[18]

Siha fell into disarray after Sinare's passing, and all unresolved succession disputes erupted once more. A faction in old Samake favoured the success of Jacobus, a young uncircumcised lad who was Sinare's son. A party sought Maanya's brother Tarawia, arguing that the Mmari clan had the right to rule as they had done before Sinare's ascension. Mangi Sianga of Kibosho backed Tarawia, while Mangi Ngulelo of Machame backed Jacobus.[16]

The ongoing conflict between these two foreign powers was unmatched in Antiquity in terms of its severity and longevity. It was obvious that everyone would support the opposing position in any debate. While Kibosho, which had previously backed the rival Orio clan in Samake during the reign of Mangi Sina, now naturally lends its support to the Mmari clan, hostile as that clan was to the Machame which contributed to the fall of Ngalami, Machame under Mangi Shangali had already supported the Kileo clan in the person of Sinare.[19]

Any Mmari clan candidate never had the opportunity to receive a fair hearing from the local official of the European administrative power, whether German or British, who made the final choice, whether in 1905 or later. This was the case when the mangi of Siha's succession was chosen in 1900, 1905, 1919, 1920, and 1927. He was chosen in the following way. The two candidates for the throne, Jacobus and Tarawia, were called to the boma, the German administrative centre in Moshi, together with their followers. There, a German commander overheard their disagreements and made a decision for them. Some of Mangi Ngulelo's warriors from Machame had been sent to speak up for Jacobus. The German officer had to rely on Hamisi Muro, a Machame man, in addition to the official interpreter in the Boma to translate the arguments of both sides from Kichagga into Swahili that he could understand.[19]

Hamisi's version of the conflicting claims can be inferred not only from the fact that Ngulelo served as his chief but also from the fact that he was friends with the Kileo family and had previously prevented the German authorities from hanging Jacobus' father Sinare when serving as mangi of Siha. Jacobus had gone down in his underwear, so the German officer decided in his favor and made arrangements for him to be dressed. A drastic but understandable deviation from Chagga custom, which calls for a Mangi to be established in his own kingdom among his people, followed by an immediate installation of him as Mangi of Siha, the only time a Mangi has been installed on Kilimanjaro on a boma. Tarawia was then deported to Uru.[19]

With one confusing interruption in 1919 when Matolo of the Orio clan assumed power but was swiftly deposed, Jacob's authority continued until 1920. Jacob did not make an effort to appease the Mmari and Mwandri tribes and instead continued to rule the country from Old Samake. He is regarded as having been a strong and brutal king. He would ride his horse while tying the victim to it as punishment. If you gave him a skinny goat, he would beat it against a wall until it died. He would ask someone to kneel down when he was holding a baraza(Meeting place) so he could sit on his back until the meeting was finished. He used beatings and sexual abuse as a form of control.[18]

Although Jacob's mangi practices were not novel to Kilimanjaro, they were carried out with a sternness that eventually prompted people to complain about him to the British Administration. By 1920, indications that his power was waning allowed Jacob to effectively seek a justification for retiring. Once more, Siha people disagreed over who should succeed the current mangi. A candidate from the Mmari clan named Barnaba (Ngalami's eldest son) was put forth by some, and Jacob used his power to make things complicated. The argument was referred to Major Dundas, the newly assigned British officer at the boma(German fort). He made the decision to name ex-mangi Malamya of Kibosho, an outsider, as Mangi of Siha.[18]

From 1920 through 1927, Malamya served as Siha's mangi. It is said that he enjoyed the support of the populace and established a tranquil regime. Even in Wanri, the heart of the kingdom, where the Mmari and Mwandri clans were the most powerful, he was able to establish the baraza. In 1927, tax money from the Siha Native Treasury vanished, and Malamya was falsely accused of stealing a calf that the Maasai gave him after they had stolen it from some Europeans. The British swiftly removed him, and following his return to Kibosho, he was assassinated.[20]

Simeon, son of Nkunde of the Mwandri clan in Wanri was appointed as Mangi of Siha soon after, but British administrative officer F.C. Hallier compelled him to retire after a few months. Mangi Abdiel, the son of Shangali of Machame, desired exclusive access to Siha. As a result, Hallier accepted the case after hearing from his father and ex-mangi Jacob that they both backed the boy. Siha and Machame were both under Abdiel's control. through a family member of the Machame clan named Gideon son of Nassua, indirectly governing Siha. Gideon's leadership over Siha was ruthless, productive, and continuous from 1927 until 1945. His son John ruled as mangi from 1945 onwards.[21]

At the newly established divisional council of Hai, the Siha people elected Simeon Kitika of the Mmari clan to represent them; Mangi Abdiel rejected their selection as inappropriate and chose Jacob in its place. Until his death in 1962, he was in power.[22]

References

- ↑ "Chagga people- history, religion, culture and more". United Republic of Tanzania. 2021. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ↑ R.O. “The Chagga and Their Chiefs - History of the Chagga People of Kilimanjaro. By Kathleen M. Stahl. The Hague: Mouton, 1964. Pp. 394, Maps. 32 Guilders.” The Journal of African History, vol. 5, no. 3, 1964, pp. 462–464., doi:10.1017/S0021853700005181.

- 1 2 Ekemode, Gabriel Ogunniyi. “German Rule in North-East Tanzania, 1885-1914.” Eprints.soas.ac.uk, 1 Jan. 1973, https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/33905/.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 61. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Chandler, Caitlin L. "Skeletons from Kilimanjaro; East African Families Seek to Reclaim the Remains of Their Ancestors from German Colonial Collections." The Dial, 23 Mar. 2023, www.thedial.world/issue-3/germany-reparations-tanzania-skeletons-maji-maji-rebellion.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 61. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 69. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 70. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 70. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 71. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 72. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 73. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 74. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 75. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 76. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Iliffe, John (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780511584114.

- 1 2 3 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 78. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- 1 2 3 Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 79. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 80. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ↑ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 82. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.