| No Earthly Connection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 1976 | |||

| Recorded | January–March 1976 | |||

| Studio | Château d'Hérouville (Herouville, France) | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 42:13 | |||

| Label | A&M | |||

| Producer | Rick Wakeman | |||

| Rick Wakeman chronology | ||||

| ||||

No Earthly Connection is a studio album by English keyboardist Rick Wakeman, released in April 1976 on A&M Records. After touring worldwide in late 1975 in support of his previous studio album The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table (1975), Wakeman retreated to Herouville, France to record a new studio album with his rock band, the English Rock Ensemble. He based its material on a part fictional and non-fictional autobiographical account of music that incorporates historical, futuristic, and science-fiction themes.

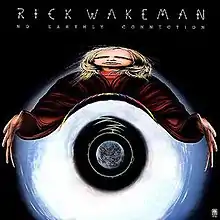

No Earthly Connection peaked at number 9 on the UK Albums Chart and number 67 on the US Billboard 200. Its front cover features a distorted image of Wakeman that is corrected with a mirror sheet supplied with the album. Wakeman supported No Earthly Connection with a world tour that ended in August 1976, after which he disbanded his group for four years. In November 2016, the album was remastered and released on CD and vinyl with a live recording from the 1976 tour.

Background and writing

In December 1975, the 26-year-old Wakeman finished his three-month tour of North America and Brazil in following the release of his recent studio album The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table (1975) and the soundtrack album Lisztomania (1975).[1] After a brief rest period, he relocated to Herouville, France in January 1976 to record a new studio album No Earthly Connection with his rock band, The English Rock Ensemble.[2] His previous two albums, Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1974) and King Arthur, were concept albums that featured a symphony orchestra and choir that were costly to produce. When it came to recording No Earthly Connection, management at A&M Records insisted to Wakeman that an album with an orchestra and choir was no longer an option.[3] For his 1975 tour, Wakeman had added two brass players to now six-piece band, Martyn Shields on trumpet and Reg Brooks on trombone. Guitarist Jeffrey Crampton was also replaced by John Dunsterville.[1][2]

During a stop in Miami, Florida on the 1975 tour, a time when material for the album was being prepared, Wakeman claimed he saw a UFO in the night sky at his beach house and alerted bassist Roger Newell as a witness. He resisted to inform others at first as he thought they would merely disbelieve him, despite the incident attracting local news coverage on the following day. Wakeman used the incident to write musical themes that entered his mind as he thought of it, much of which was put down during flights on the 1975 tour.[4] Wakeman also wrote some passages in the airplane toilet.[5] Wakeman ended up writing a considerable amount of music during the making of the album as he was determined to record everything that came to mind, but had to throw out approximately sixty percent of the material.[6] He later revealed that he wrote it without playing any of it back to listen.[7] Wakeman said he could not explain half of the album, and gave the album its title because of his inability to fully explain it. Biographer Dan Wooding believe the album is Wakeman's "own personal journey into the unknown".[4]

Recording

Wakeman recalled the difficulty in getting A&M to understand and support No Earthly Connection partly due to the length of "Music Reincarnate" which occupied the entire first side and finish on part of the second. The label suggested to have parts cut in order for the track to fit on a single side, but Wakeman refused as its length was what he intended the piece to be. He also refused to extend the piece to fill both sides entirely as it resembled the problem he had with the Yes album Tales from Topographic Oceans (1973), a double album containing four, side long tracks that were deliberately extended to fit each side of a vinyl, an idea that Wakeman disagreed with.[3] Instead, Wakeman filled the second side with two "related story wise" tracks, "The Prisoner" and "The Lost Cycle".[2][3]

The album was recorded from January to March 1976 with Wakeman credited as the producer. He was joined by engineer Paul Tregurtha and engineering assistant Didier Utard.[2] Wakeman lived in the studio building with the engineers for the entire time, with his band members staying for a large amount of it. At one point in the recording, Wakeman woke up during the night after he thought of a particular sound he wished to put onto tape and woke an engineer to record it. "There was something quite magical about that and I've never been able to do it ever again".[3] When Wakeman needed a waterfall effect and felt dissatisfied with a vinyl of pre-recorded waterfall sounds, he got his band mates to pour jugs of water into a tin bathtub that was placed in a cellar for echo and recorded it. He was dissatisfied with the result and it was too short, so he suggested they all drink wine and urinate in the bath at the same time.[8]

Upon completion, Wakeman accidentally flicked some marmalade onto the master tape as he was eating. This resulted in Tregurtha spending several hours carefully washing off around 300 feet of tape using soap and water without damaging it. Should the tape have become useless, Wakeman said they would have had to fly the band over and rerecord the parts.[9] In a 2003 interview, Wakeman said he could hear any section of No Earthly Connection and recall what time of the day he put them to tape.[3] During the recording, Wakeman found himself sitting on a wall crying in a village miles from the studio. "I still don't know how I got there or why I was crying" and added, "It was as if my mind had blown a fuse".[10] He said his album Out There (2003) is, in many ways, a sequel to No Earthly Connection.[3]

Music

No Earthly Connection marked a change in Wakeman's musical direction. He retained the progressive rock style in his music, but made a conscious decision to make a more serious album without the comedic and tongue in cheek elements he had incorporated in his previous works. He wished to write something "that I believed in fervently".[3] Wakeman said it is a part fictional and non-fictional musical autobiography based on things people know exist but unsure as to why or cannot explain, the question of life and its different forms, evolution, and flying saucers. He took a human soul as his main narrative and explained it in musical terms, which involves the idea of everyone born with a "musical soul" that is reincarnated into another person once they die.[11] Though none of the parts to "Musical Reincarnate" details what happens to the person in question, Wakeman noted the song's narrative is merely a possibility of what could.[11] "The Warning" concerns the birth of a child and not making any decisions for one's self.[11] "The Spaceman" is based on the idea of some people almost ruining their lives by dropping out of something that they are good at,[11] which is followed by "The Realisation" where the individual, now elderly, reflects on its life, things they regret or went wrong, and realise it is too late to develop their given musical soul.[10] "The Prisoner" concerns someone being punished before they meet someone, as written in "The Maker", who informs them they are no longer of use and is left to wander in outer space without any destination.[10] "The Lost Cycle" deals with a gap in evolution with the possibility of advanced civilisations on distant planets.[12]

Prior to the album's release, A&M publicity director Mike Ledgerwood organised an exclusive preview event for several news reporters and funded a bus trip from London to the studio.[7] However, when news of Wakeman's absence from the reception spread, they learned on the following day that he had listened to the entire album for the first time upon completion and freaked out, partly due to the idea of playing the material on stage, and had driven home in England.[9] His manager Brian Lane then organised an agricultural aircraft to take Wakeman back to the studio and greet the press. Wooding wrote: "The missing Rick reappeared next day showing ravages of exhaustion. A nervous tic disturbed his face. His usually impressive blonde hair looked bedraggled. His skin was red and his eyes betrayed weariness and wariness".[9]

Release

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Allmusic | |

The original LP contained a small square sheet of reflective plastic that could be curved into a cylinder, which when placed on the front cover allowed the viewer to see the cover anamorphic drawing undistorted and with a 3D-like effect. A barely noticeable thin colourful arc on the cover (see picture) appeared then as a rainbow keyboard about to be played by Wakeman's hands, in consonance with the album's theme of a creation myth based on music. The album is currently available through Real Gone Music.[14]

Track listing

All lyrics and music by Rick Wakeman.[2]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Music Reincarnate"

| 20:24 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Music Reincarnate (Continued)"

| 7:34 |

| 2. | "The Prisoner" | 7:00 |

| 3. | "The Lost Cycle" | 7:00 |

Personnel

Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[2]

- Musicians

- Rick Wakeman – Mander pipe organ, Hammond C3 organ, 9' Steinway grand piano, RMI Electra piano, Hohner clavinet, Moog synthesizer, Baldwin electric harpsichord, upright honky-tonk piano, Fender Rhodes 88 electric piano, Mellotron, Godwin organ with Sisme Rotary-Cabinet, Systech effects pedals

- Ashley Holt – vocals

- Roger Newell – bass guitar, bass pedals, vocals

- John Dunsterville – acoustic and electric guitars, mandolin, vocals

- Tony Fernandez – drums, percussion

- Martyn Shields – trumpet, flugelhorn, French horn, vocals

- Reg Brooks – trombone, bass trombone, vocals

- Production

- Rick Wakeman – production

- Paul Tregurtha – engineer

- Didier Utard – assistant engineer

- Toby Errington – crew in France

- Jake Berry – crew in France

- John Cleary – crew in England

- Tony Merrell – crew in England

- Tony Powell – crew in England

- Fred Randall – personal manager

- Fabio Nicoli – art direction

- Mike Doud – concept/design

- Chris Moore – cover illustrations

- Geoff Halpin – logo design

- George Snow – inner sleeve design

- Mike Putland – photography

Charts

| Chart (1976) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[15] | 35 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[16] | 74 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[17] | 15 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[18] | 44 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[19] | 9 |

| US Billboard 200[20] | 67 |

References

- 1 2 Rick Wakeman: No Earthly Connection [Press kit] (PDF). A&M Records. April 1976.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 No Earthly Connection (Media notes). Wakeman, Rick. A&M Records. 1976. AMLK 64583.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Morse, Tim (21 March 2003). "Conversation with Rick Wakeman [NFTE #275]". Notes from the Edge. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- 1 2 Wooding 1978, p. 156.

- ↑ Wooding 1978, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Wooding 1978, p. 160.

- 1 2 Wooding 1978, p. 162.

- ↑ Wakeman 2009, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Wooding 1978, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Wooding 1978, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 4 Wooding 1978, p. 157.

- ↑ Wooding 1978, p. 159.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. No Earthly Connection at AllMusic

- ↑ "Real Gone Music - News - Rick Wakeman". Realgonemusic.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ↑ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 4143b". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Norwegiancharts.com – Rick Wakeman – No Earthly Connection". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Swedishcharts.com – Rick Wakeman – No Earthly Connection". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Rick Wakeman Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Bibliography

- Wakeman, Rick (2009). Grumpy Old Rock Star: and Other Wondrous Stories. Random House. ISBN 978-1-409-05032-2.

- Wooding, Dan (1978). Rick Wakeman: The Caped Crusader. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0-709-16487-6.