| Northeastern Highlands Ecoregion | |

|---|---|

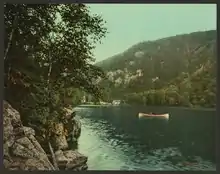

A mountain forest in Vermont | |

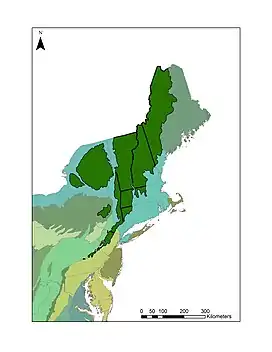

Northeastern Highlands region denoted in forest green | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | temperate broadleaf forest |

| Geography | |

| Area | 122,406.62 km2 (47,261.46 sq mi) |

| Country | United States |

| Elevation | 365 meters |

| Coordinates | 42°N, -73°W |

| Climate type | Warm summer humid continental |

| Soil types | Spodosols |

The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion is a Level III ecoregion designated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the U.S. states of Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The ecoregion extends from the northern tip of Maine and runs south along the Appalachian Mountain Range into eastern Pennsylvania. Discontiguous sections are located among New York's Adirondack Mountains, Catskill Range, and Tug Hill. The largest portion of the Northeastern Highlands ecoregion encompasses several sub mountain ranges including the Berkshires, Green Mountains, Taconic, and White Mountains.

The mountainous region is underlain by metamorphic rock and glacial till. The ecoregion is flanked by several others including the: Acadian Plains and Hills, Eastern Great Lakes Lowlands, Northeastern Coastal Zone, Northern Allegheny Plateau, Ridge and Valley, and Northern Piedmont ecoregions.[1] The elevation generally ranges from 182 meters (597 ft) to 1,916.6 meters (6,288 ft) at the top of Mount Washington, the region's highest and most prominent point. The region is characterized by hot humid summers and cold snowy winters. The nutrient-poor spodosols and other cryic soil types of the region support boreal (north) and broadleaf (south) forests that cover the majority of the region. Ecotourism, forestry, and agriculture are the predominant land uses of the sparsely populated region.[2] Though much of the region was once cleared to make farmland, much of it has reverted into natural forested areas; to a lesser extent, dairy and crops are still grown in lowland valleys and beef cattle on upland pastures. The ecoregion has been subdivided into thirty-three Level IV ecoregions.[2]

Native wild animals of the area include American black bear, white-tailed deer, moose, bobcat, coyote, skunk, raccoon, chipmunk, squirrel, opossum, porcupine, fisher, eastern turkey, northern bobwhite, great blue heron, ducks, loons, and a host of other bird, reptile, amphibian, and fish species.[3] The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion was within the range of other large mammals at the onset of European settlement; these included boreal woodland caribou,[4] which inhabited northern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, as well as American bison,[5] which judicious estimates have placed in western portions of the Catskills and Adirondacks. Puma and eastern elk, too, once inhabited a majority of the region.

Before European settlement, the region was inhabited by two principal indigenous groups: the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples. The Algonquian community represents one of the largest and most geographically dispersed Native American language groups. They held prominence along the Atlantic Coast and within the inland areas adjacent to the St. Lawrence River and the vicinity of the Great Lakes. On the other hand, the Iroquoian peoples form an ethnolinguistic collective originating from the eastern expanse of North America. Their traditional territories, often denoted as "Iroquoia" by scholarly circles, extend from the northern mouth of the St. Lawrence River down to present-day North Carolina in the southern reaches.

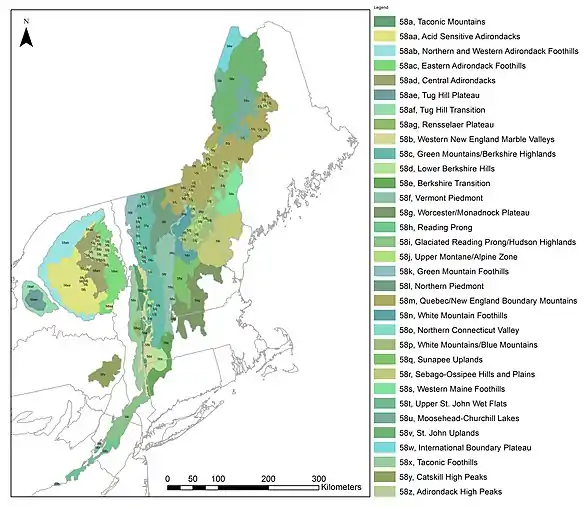

Level IV ecoregions

58a. Taconic Mountains

The Taconic Mountains ecoregion runs north-south for 150 miles (240 km) along New York's eastern border, spanning eastern New York, southwestern Vermont, far western Massachusetts, and the northwest corner of Connecticut. The range exhibits a rugged appearance despite lower elevations compared to the nearby Catskills and Adirondacks, with elevations of 1,000 to 2,100 feet (300 to 640 m) and local relief of 600 to 800 feet (180 to 240 m). Predominantly metamorphic bedrock gives rise to a varied landscape of steep and gentle slopes, narrow valleys, springs, and caves due to soluble limestone. The humid continental climate, frost-free growing season of 90-135 days, and slightly elevated precipitation characterize the region. The northern-southern expanse leads to discernible forest type shifts.

Northern hardwood forests thrive on cooler mid-to-high elevation sites, housing sugar maple, American beech, American basswood, and yellow birch, with spruce-fir at highest elevations. Oak-hickory forests with species like northern red oak and shagbark hickory dominate lower, drier slopes. Pitch pine and bear oak cover the highest elevations in the south. Isolated old-growth forests remain in Mount Washington State Forest and Mount Everett State Reservation.

The area is sparsely populated with minimal agricultural use; forests encompass most of the region. It borders the Taconic Foothills to the west, the Rensselaer Plateau to the center, and the Western New England Marble Valleys to the east, with a small border with the Champlain Lowlands to the north. [6]

Taconic Ridge State Park and Taconic Trail State Park are components of the Taconic Mountains region, providing protected spaces for both conservation and recreation. Taconic Ridge State Park spans areas of New York and Massachusetts, featuring rugged landscapes, diverse ecosystems, and panoramic views. This park includes portions of the Taconic Crest Trail. Taconic Trail State Park, located in Massachusetts, encompasses several woodlands and offers a network of trails, including sections of the Appalachian Trail.

The highest peak in the Taconic Mountains is Mount Equinox in Vermont at 3,840 feet (1,170 m). Despite being mostly private property, it contains sizable state forests, parks, and protected preserves. Conservation efforts involve organizations like the Berkshire Natural Resources Council and The Nature Conservancy, with designated areas under the Forest Legacy Program.

58aa. Acid Sensitive Adirondacks

The Acid Sensitive Adirondacks derive their name from the underlying bedrock which has a low acid-neutralizing capacity and is one of the regions of the Northeastern Highlands that has been most affected by acid rain. The Acid Sensitive Adirondacks constitute the largest level IV region of the Adirondack Mountains. Acid rain has acidified the region's lakes to the point where they are uninhabitable for fish; terrestrial effects of acid rain have resulted in leaching of calcium and release of aluminum, which has resulted in tree mortality. Tree cover in the region is dominated by conifers including red, white, and black spruce, as well as balsam fir, red maple, yellow birch, and black cherry.[7][8]

The Acid Sensitive Adirondacks are in the southwestern portion of the Adirondack Park and are composed of the Independence River Wild Forest, the Black River Wild Forest, and the Moose River Plains. The western gateway community of Old Forge is central to the eco-region.

58ab. Northern and Western Adirondack Foothills

The Northern and Western Adirondack Foothills encompass a curved expanse in upstate New York, encircling the higher elevations of the Adirondacks to the north, west, and southwest. This area serves as a transitional zone between the mountainous terrain and the adjacent lowlands. The landscape gradually ascends from around 1,000 to 1,600 feet (300 to 490 m) in elevation across a span of 20 to 25 miles (32 to 40 km). The area is blanketed by thick glacial deposits, which hinder stream drainage in multiple sections. Despite its steep incline, the region generally features a high water table and abundant wetlands, an unusual characteristic. The narrowest and most abrupt elevation shifts occur in the southwest and western sectors. Conversely, the northern part of the region widens slightly, showcasing a more gentle gradient and smoother slopes.

Originally, spruce trees dominated the forests here. However, extensive logging activities led to their depletion, with only a few specific soil types supporting their resurgence. Presently, the area is dominated by second-growth northern hardwood forests, including tree species like sugar maple, American beech, black cherry, and yellow birch. The western foothills and northern outwash areas host substantial populations of eastern white pine, while aspen and birch prevail more in the north. Areas with shallow or water-saturated soils foster coniferous forests composed of red spruce, white spruce, black spruce, and balsam fir. Notably, bogs are home to dominant black spruce and tamarack trees, accompanied by understory vegetation such as sheep laurel and labrador tea. Agricultural activities are limited in this vicinity, primarily focused on cultivating forage crops. Logging stands as a more active land use, with significant public lands preserved for wildlife habitats and recreational and tourism pursuits. Surrounding the Acid-Sensitive Adirondacks, except for the northeast where it borders the Central Adirondacks in a single location, this region holds a unique position. Towards the northeastern extremity, where the foothills envelop the Adirondacks, the Eastern Adirondack Foothills border it. This adjoining region, distinguished ecologically, is treated as a distinct entity. Lowering in elevation, the Northern and Western Adirondack Foothills neighbor the Upper St. Lawrence Valley to the north and west, along with the Mohawk Valley to the south and southwest.[9]

58ac. Eastern Adirondack Foothills

The Eastern Adirondack Foothills serve as a pivotal intermediary zone nestled between the western Adirondacks and the lowlands situated to the east. This geographical domain envelops the eastern and southeastern peripheries of the Adirondack Mountains, manifesting climatic and geological distinctions that set it apart from the foothills encompassing the mountains' northern, western, and southwestern sectors.

In the northern expanse of this locale, the predominant bedrock substratum primarily comprises limestone and anorthosite formations. Meanwhile, the southern reaches of this area showcase a blend of these foundational rock types in conjunction with others.

The climatic conditions prevailing within this region exhibit characteristics of a humid continental climate. Particularly pronounced in the northern domain, the rain shadow effect induces lower precipitation levels than those typically encountered in the broader surroundings. However, the moisture content remains sufficiently elevated to sustain luxuriant forests. The topographical configuration is accentuated by the presence of expansive valleys incised by the Saranac and Ausable rivers in the northeast. These valleys facilitate the penetration of milder climatic influences from lower-lying areas into the foothills. In the southern sector, the landscape assumes a more rugged demeanor, accompanied by a relatively abrupt transition. This results in a semblance of climatic consistency throughout this extensive north-south stretch, thereby mitigating the impact of colder winters as one proceeds northward. The average frost-free interval spans between 90 and 145 days.

Historically, the primeval forest cover encompassing this realm was characterized by northern hardwood forests, interspersed with select species from the Appalachian oak forest biome at the lower gradients that abut the Hudson Valley and Champlain Lowlands.

Despite its modest population density, the Eastern Adirondack Foothills are more settled than their higher-altitude counterparts within the Adirondacks. The majority of development is concentrated along major thoroughfares traversing the territory, converging within a handful of petite municipalities situated along these arterial routes.

Geographically, this region is flanked along a substantial length of its perimeter by the Champlain Lowlands to the east. To the south, it interfaces with the Hudson Valley in the southeast and the Mohawk Valley in the southwest. At its northern extremity, it abuts the Northern and Western Adirondack Foothills—a distinct geological and climatic precinct. On its western boundary lie the elevated Central Adirondacks and the Adirondack High Peaks, while at the southern terminus, it interfaces with the Acid Sensitive Adirondacks, which also enclose a discrete enclave encircled by the Eastern Adirondack Foothills.

This region's multifaceted identity thus emerges as an interface between diverse geological formations, climatic influences, and ecological nuances, further accentuated by the subtle interplay of human settlements, agricultural economics, ecotourism prospects, and the recreational havens presented by its parks and natural spaces.[10]

58ad. Central Adirondacks

The Central Adirondacks, a mid-elevation region of the Adirondacks, feature acid-neutralizing bedrock, protecting waterways from acidification. Spanning an irregular shape within the Adirondack region, this area has elevations of 442 to 1,024 meters (1,450 to 3,360 ft), with low-to-moderate relief mountains and hills. Historically covered by spruce and white pine forests, the landscape now holds earlier-successional hardwood communities, conifer-heavy variants of northern hardwood forests, and lakeside mixes of pine. While sparsely populated, the region supports small towns, tourism, recreation, and logging. Almost entirely forested, it is bordered by the Acid Sensitive Adirondacks to the west and, to the east, by the higher-elevation Adirondack High Peaks and the Eastern Adirondack Foothills to the north and south.

Reported land use and towns within the Central Adirondacks highlight its limited agricultural presence, with extensive public land used primarily for tourism, recreation, and logging. It is central to the Adirondack Park, a vast state-protected area in Upstate New York, renowned for its diverse ecosystems, outdoor recreational opportunities, and extensive forested landscapes. [11]

58ae. Tug Hill Plateau

The Tug Hill Plateau Eco-region, located in upstate New York, is a distinctive landscape shaped by its unique combination of geographical factors. Spanning an elevated area east of Lake Ontario and the Tug Hill Upland, this plateau experiences a humid continental climate with precipitation influenced by both lake effect and orographic lift. These meteorological phenomena bring substantial rainfall and snowfall to the region, creating belts of high precipitation downwind of the Great Lakes.

The core of the Tug Hill Plateau rises due to its underlying Oswego sandstone, which is less erodible compared to the surrounding shales and siltstones. This elevation, combined with the plateau's flat topography covered by dense glacial till, contributes to a landscape of swamps and bogs. The area's high annual precipitation and relatively flat terrain have led to the formation of numerous wetlands.

Similar to the Rensselaer Plateau, the Tug Hill Plateau is notable for its expansive forested lands that play a vital role in supporting wildlife habitat and maintaining water quality. The region's history includes a period of widespread logging and farm abandonment, followed by reforestation efforts with successional hardwoods and large pine plantations.[12]

Tug Hill State Forest and Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area collectively form a vital conservation corridor within eco region. These protected areas play a role in preserving the region's natural environment and diverse ecosystems.[13] Tug Hill State Forest encompasses 12,242 acres (49.54 km2) of forests, wetlands, and uplands, providing recreational opportunities like hiking, camping, and wildlife observation. On the other hand, Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area is dedicated to wildlife conservation and offers a haven for various species. These interconnected conservation areas contribute significantly to maintaining the ecological balance of the Tug Hill Plateau, showcasing the region's commitment to safeguarding its natural heritage.

58af. Tug Hill Transition

The Tug Hill Transition Eco-region encircles the Tug Hill Plateau in New York state, forming a distinctive doughnut-shaped area that serves as a bridge between the plateau and the surrounding lowlands. This region features sloping topography, a contrast to the adjacent areas it borders. Geologically, it differs from the plateau, characterized by siltstone and shale, leading to more fertile soils suitable for agriculture. The transition is marked by waterfalls along its central border with the plateau, leading into deep gorges.

The climate in this region resembles that of the plateau, but with slightly less intensity. It experiences a humid continental climate with relatively higher precipitation in conjunction with cool temperatures. The proximity to Lake Ontario and orographic lift contribute to the increased moisture content in the air, resulting in elevated precipitation levels. The frost-free growing season averages 100-140 days, falling between the plateau's and the surrounding lowlands' durations.

The original forest cover, comprising northern hardwoods like sugar maple, American beech, yellow birch, and eastern hemlock, has been mostly cleared. The current landscape is a mix of cultivated farmland and regenerating forests. These forests are in earlier successional stages and include a combination of tree species such as sugar maple, black cherry, white ash, and red maple.[14]

Tug Hill State Forest and Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area create an essential conservation corridor, preserving the region's diverse ecosystems and natural environment.[13] Tug Hill State Forest offers recreational activities in forests, wetlands, and uplands, while Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area focuses on wildlife conservation. Together, they maintain the ecological equilibrium of the Tug Hill Plateau and underscore the region's dedication to protecting its natural heritage.[13]

.JPG.webp)

58ag. Rensselaer Plateau

Nestled in the heart of Rensselaer County, New York, the Rensselaer Plateau constitutes a distinctive and geologically intriguing area. This small, roughly circular region is characterized by a geological composition centered on greywacke, a robust quartzite-dominated sandstone renowned for its erosion-resistant nature. Elevation within the plateau ranges from 1,000 to 1,800 feet (300 to 550 m), with its terrain marked by gentle undulations and a minor local relief, generally reaching 20 to 50 feet (6.1 to 15.2 m), save for the periphery where elevation differences peak at 400 feet (120 m). The presence of occasional shale and conglomerate deposits alongside a rocky glacial till further accentuate the region's geological makeup. The prevailing thin soils punctuate the uplands, interspersed with a network of kettle ponds and small wetlands.

Amidst the distinct geological framework, the Rensselaer Plateau boasts an ecosystem characterized by attributes more commonly found in northern latitudes. The climate here is notably colder than the neighboring low-lying areas, with a frost-free growing season spanning 90 to 135 days. The forest canopy predominantly comprises a medley of northern hardwoods, accompanied by the likes of red spruce, balsam fir, and various wetland vegetation communities. Acidic sphagnum bogs, graced with black spruce and tamarack, and sedge meadows lend a unique texture to the landscape. Adjacent to wetlands, spruce flats host an ensemble of red spruce, white spruce, black spruce, and balsam fir. Notably, south-facing slopes around the periphery feature pockets of Appalachian oak–hickory forest, once graced by the presence of the American chestnut.

Having undergone logging activities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the current forest stands on the plateau have regenerated as second-growth forests. Despite being relatively modest in protected public lands, this region hosts remarkably intact forest cover, rendering it a sanctuary of significant wildlife value. Its sparse population and limited agricultural activity mirror the challenge posed by its rocky, nutrient-poor soils and abbreviated growing season. The allure of tourism and recreational pursuits, coupled with modest mining endeavors related to the greywacke, contribute to the region's economy. Noteworthy public lands encompass Cherry Plain State Park, Pittstown State Forest, and Grafton Lakes State Park, collectively preserving the essence of this exceptional region.

The Rensselaer Plateau is hemmed in by the Taconic Foothills in most directions, with an exception to the east where it directly abuts the Taconic Mountains. This eastern boundary is demarcated by a slender, steep-walled valley, chiseled by the meandering course of the Little Hoosic River.[15][16]

58b. Western New England Marble Valleys

58c. Green Mountains/Berkshire Highlands

The Green Mountains (Vermont)/Berkshire Highlands (Massachusetts) are part of the same level IV ecoregion, but are defined by different names per their political state boundaries. The region is dominated by steep mountainsides with prominence up to 764 meters (2,507 ft). Like most of the Northeastern Highlands ecoregion, the bedrock consists of metamorphic and glacial till and the soils are acidic, coarse, and low in nutrients. The area is primarily second growth forest, which has returned as a mixed conifer and hardwood stand. Common tree species include red oak, sugar maple, American beech, yellow birch, eastern hemlock, white pine, white ash, basswood, tamarack, black spruce, balsam fir, and white birch.[17]

.jpg.webp)

This region includes the towns of Killington, Waterbury, and Stowe, Vermont, and Charlemont, Massachusetts. The primary land use includes active tourism, such as skiing, hiking, biking, and snowmobiling, as well as forestry, maple syrup production, cattle, and hay production.[17][18] This region is also home to several state parks and national woodlands including the Green Mountain National Forest, Calvin Coolidge, Camels Hump, Mount Mansfield, and Okemo State Forests, and Woodford, Molly Stark, Lake Shaftsbury, Fort Dummer, Emerald Lake, Lowell Lake, Lake St. Catherine, Camp Plymouth, Mount Ascutney, Wilgus, and Hazen's Notch state parks.

58d. Lower Berkshire Hills

58e. Berkshire Transition

58f. Vermont Piedmont

58g. Worcester/Monadnock Plateau

58h. Reading Prong

58i. Glaciated Reading Prong/Hudson Highlands

58j. Upper Montane/Alpine Zone

The Northeastern Upper Montane/Alpine Zone is largely discontiguous, as it appears only at the highest peaks in the region. The ecozone is characterized by shallow acidic soils and nadir soils and by a short (40-80 day) frost-free season.[2] The region is typically the coldest of the Northeastern Highlands. Precipitation is high in all seasons. (Mt. Mansfield is Vermont's wettest location with ~2,002.5 mm (78.84 in) of precipitation on average;[19] Mt. Washington in New Hampshire tips the scales with an average of 2,463.8 mm (97.00 in) of precipitation per year.)

The Upper Montane Zone generally occurs above 3,500 feet (1,070 m) where mountain birch, balsam fir and black spruce are dominant. Above the tree line at 4,500 feet (1,370 m), alpine meadows and low-growing shrubs persist; these include lapland rosebay, northern blueberry, dwarf birch, bog blueberry, highland rush, bigelow's sedge and shrubby fivefingers.[20][21] These peaks, island refuges, are relics of a larger ecosystem that covered New England when the last glaciers melted in the region ~12,000 years ago.[22] These unique ecosystems are home to several insect species, like the endangered White Mountain fritillary butterfly. The American pipit is a unique bird species and the only obligate alpine nesting bird in New England.[22]

58k. Green Mountain Foothills

The Green Mountain Foothills (aka Champlain hills) form a transitional ecoregion between the northern Green Mountains on the east to the Champlain Lowlands on the west. This region is hilly and ranges in elevation from 122 to 457 meters (400 to 1,499 ft), with the high point on Fletcher Mountain (653 meters (2,142 ft)). The area is composed mostly of frigid spodosols; sandy, coarse-loamy, and fine-loamy soils and a dense mixed forest. The region, although reforested, it still mosaiced by dairy, hay, and pasture crops.

The Green Mountains Foothills Eco-region is home to several state parks. Among these parks, Jamaica State Park stands out for its setting along the West River, offering picnicking, camping, and water-based activities. Fort Dummer State Park, situated on a historical site, provides hiking trails and views of the Connecticut River Valley. Gifford Woods State Park has forested areas and is near the Appalachian Trail.

58l. Northern Piedmont

The Northern Piedmont ecoregion in Vermont is distinguished from the Vermont Piedmont by it northern location and associated colder climate. It is sometimes referred to as the Northern Vermont Piedmont and is distinct from the Northern piedmont ecoregion extending from New York to Virginia. Bedrock in this Vermont region is mostly limestone, phyllite, mica, schist, quartzite, and slate, with lesser areas composed of granite gneiss; hence it is different from surrounding granite mountain ranges. The Northern Piedmont is mountainous with large open valleys, making it better suited to farming than the hillier terrain of the neighboring Green Mountains, though the colder climate means that cropping or grazing seasons are short (100-140 growing days). The climate is more seasonal than in the southerly humid continental range, with a seasonal summer monsoon which is twice that of winter snowfall. Trees in the region are similar to those in the Green Mountains, wherein northern hardwoods dominate on lower elevation terrain and mixed hardwood and hemlock or spruce–fir forests are supported on upland terrain.

Agriculture abounds in the Northeast Kingdom and commonly includes production of hay, cattle corn, oats, vegetables, and grazing land. The area is sparsely populated, but includes Vermont's capitol, Montpelier (the least populated state capital in the US) and the city of Barre. Brighton State Park is located in the Northern Piedmont. This area and the Quebec/New England Boundary Mountains support the most moose in Vermont and New Hampshire.[23]

58m. Quebec/New England Boundary Mountains

The Boundary Mountains extend between Quebec and New England from northeast Vermont into Central Maine. The Longfellow Mountains (named for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) are within this region, as is Maine's Baxter State Park. The area is dominated by low, open mountains, interspersed with deep ponds. Likewise, Lake Willoughby, a National Natural Landmark in Vermont, is a good example of a fjord-like deep lake surrounded by tall mountains. Like the other Northeast Highland ecoregions, the Quebec/New England Boundary Mountains are cold, yet humid continental with an average of 85-125 frost-free days. The region is mostly forested and dominated by conifers, with some mixed and deciduous forests. High elevation regions are mostly spruce-fir, red spruce, balsam fir, and mountain, paper, and yellow birch. The area is sparsely populated and there is little farming; the region is mostly used for hunting, recreation, and maple syrup production.[24]

58n. White Mountain Foothills

58o. Northern Connecticut Valley

The Northern Connecticut Valley is a narrow region along the Connecticut River, bordering Vermont and New Hampshire and running between more mountainous surroundings to the east and west. The landscape comprises floodplains, terraces, and glacial deposits, with a humid continental climate. Diverse forest covers include Appalachian oak-hickory, sugar maple-oak-hickory, northern hardwood, and pine-oak-heath sandplain forests, alongside wetlands. Altered significantly by agriculture, urbanization, and transportation corridors, the area retains some forest cover, particularly along upland margins. [25]

Visitors can traverse both sides of the river, using Interstate 91 on the Vermont side for access or exploring older highways like New Hampshire Routes 10 and 12, and U.S. Route 5 in Vermont, which wind through several villages.

While formal attractions are limited, the region boasts numerous hidden gems. In Post Mills, Vermont, travelers can encounter the whimsical "Vermontasaurus," a 122-foot-long (37 m) sculpture crafted from recycled wood. Brian Boland, the sculptor and a renowned hot-air balloon designer, adds a touch of adventure with his balloon rides and exhibits of hot-air balloons and airships at Post Mills Airport.

The Upper Valley is adorned with historical sites like the Cornish-Windsor Bridge, the longest vintage covered bridge in the U.S., and Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park. This site features several sculptures, including the angel motif "Amor Caritas".

Mount Ascutney and its surrounding state park, offer opportunities for camping, hiking, mountain biking, and hang gliding. The region also encompasses horseback riding experiences at Open Acre Ranch, where riders can traverse private trails which overlook the Vermont hills and New Hampshire's White Mountains.[26]

58p. White Mountains/Blue Mountains

The White Mountains Eco-region spans portions of New Hampshire and Maine. This region is known for the White Mountains, which include several peaks over 4,000 feet (1,200 m) in elevation. Some well-known peaks within this eco-region include Mount Washington, Mount Adams, and Mount Lafayette.

The White Mountains Eco-region is marked by a mix of forested areas, lakes, and viewpoints. The area's ecosystem is predominantly cold and humid continental, with an average of 85-125 frost-free days, similar to the adjacent New England Boundary Mountains. The region experiences distinct seasons, with winter bringing heavy snowfall, making it a hub for winter sports and recreation.

Forests dominate the landscape, with conifers taking center stage in the high elevation areas. Species like spruce, fir, red spruce, balsam fir, and birch, including mountain, paper, and yellow birch, flourish in these colder climates. Mixed and deciduous forests are also present, adding to the region's biodiversity. The eco-region's natural environment extends to its lakes and rivers, some of which are flanked by tall mountains, creating fjord-like features similar to Lake Willoughby in Vermont.

The White Mountain range is a National Forest and has an array of state parks; these include as Franconia Notch State Park, Crawford Notch State Park, and White Lake State Park, provide opportunities for hiking, camping, picnicking, and wildlife observation, all within the backdrop of the White Mountains.

58q. Sunapee Uplands

58r. Sebago-Ossipee Hills and Plains

58s. Western Maine Foothills

58t. Upper St. John Wet Flats

58u. Moosehead-Churchill Lakes

58v. St. John Uplands

58w. International Boundary Plateau

58x. Taconic Foothills

58y. Catskill High Peaks

58z. Adirondack Peaks

See also

References

- ↑ "Level III Ecoregions of the Continental United States" (PDF). National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory - U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. June 17, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Griffith, G.E., Omernik, J.M., Bryce, S.A., Royte, J., Hoar, W.D., Homer, J.W., Keirstead, D., Metzler, K.J., and Hellyer, G., 2009, Ecoregions of New England (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,325,000).

- ↑ "Northeastern Highland Biophysical Region Check List". iNaturalist.ca. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "The Quiet Extinction: Caribou have vanished from Montana, and scientists fear they could be beyond saving". 19 February 2020.

- ↑ Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (2014-08-07). Plains bison and wood bison: COSEWIC assessment and status report 2013. www.canada.ca (Report). Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ↑ "Taconic Mountains". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ↑ Griffith, Glenn E.; Omernik, James M.; Johnson, Colleen Burch; Turner, Dale S. (2014). "Ecoregions of Arizona (poster)". Open-File Report. doi:10.3133/ofr20141141. ISSN 2331-1258.

- ↑ "Acid Sensitive Adirondacks". bplant.org. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "Northern and Western Adirondack Foothills". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ "Eastern Adirondack Foothills". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ "Central Adirondacks". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ↑ "Tug Hill Plateau | Natural Atlas". naturalatlas.com. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- 1 2 3 "Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area - NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation". www.dec.ny.gov. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ↑ "Tug Hill Transition". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ↑ "Rensselaer Plateau". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ "Rensselaer Plateau | Natural Atlas". naturalatlas.com. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- 1 2 "Green Mountains/Berkshire Highlands". bplant.org. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ Griffith, Glenn E.; Omernik, James M.; Johnson, Colleen Burch; Turner, Dale S. (2014). "Ecoregions of Arizona (poster)". Open-File Report. doi:10.3133/ofr20141141. ISSN 2331-1258.

- ↑ "Annual Vermont rainfall, severe weather and climate data". coolweather.net. Retrieved 2022-03-29.

- ↑ Bryce, S.A., Griffith, G.E., Omernik, J.M., Edinger, G., Indrick, S., Vargas, O., and Carlson, D. "Ecoregions of New York (Poster)", U.S. Geological Survey (2010) Web.

- ↑ Griffith, G.E., Omernik, J.M., Bryce, S.A., Royte, J., Hoar, W.D., Homer, J.W., Keirstead, D., Metzler, K.J., and Hellyer, G. "Ecoregions of New England (Poster)", U.S. Geological Survey (2009) Web.

- 1 2 "Something Wild: Life Abounds in Alpine Zones". New Hampshire Public Radio. January 27, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Moose population in North America". 18 November 2018. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "Quebec/New England Boundary Mountains". bplant.org. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Northern Connecticut Valley". bplant.org. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ↑ Tree, Christina (2014-08-04). "The "Upper Valley" | A Place of 'Unexpected Discoveries'". New England. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

_Mountain%252C_Old_Forge_NY%252C_east_view_March_3%252C_2018.jpg.webp)